L.A. lost Yuval Sharon to Detroit. Here’s what we’re missing — and what we might win back

- Share via

Detroit — Ten years after founding the Industry, America’s most mind-changing opera company, Yuval Sharon in 2020 improbably accepted the role of artistic director of Michigan Opera Theatre. He now divides his time between sustaining the Industry in L.A. and disrupting opera in Detroit, where he changed the formerly conventional company’s name to Detroit Opera. But that’s not all that he divides.

Detroit still gets traditional opera in its traditional opera house, although imaginatively spruced up, like the time Sharon staged Puccini’s “La Bohème” backward (Acts 4, 3, 2 and 1 in that order). But he also takes opera entirely out of its comfort zone. This month Sharon chose the lovely but underused 400-seat Gem Theatre, around the corner from the grander Detroit Opera House, for a sensational new production of John Cage’s “Europeras 3 & 4,” an unpredictable cornucopia of run-of-the-mill opera refashioned through chance operations into an outright operatic circus.

A few days later, Sharon announced his next Industry innovation, “The Comet/Poppea,” slated for June at the Museum of Contemporary Art’s Geffen Contemporary in L.A. Here Sharon will adapt Cage’s “Europera” principle — the allowance for all aspects of opera to unpredictably collide — with an epoch mashup juxtaposing scenes from Monteverdi’s 1643 “The Coronation of Poppea” with those from a newly commissioned experimental opera by George Lewis based on a 1920 science fiction short story by W.E.B. Du Bois.

Sharon has, in fact, been slowly taking up a Cagean operatic challenge. A dozen years ago, he startlingly staged a quasi-operatic interpretation of Cage’s 1970 “Song Books,” an almost-anything-goes theatrical endorsement of Thoreau’s call for anarchy that included the great opera star Jessye Norman. It was part of a San Francisco Symphony concert in which conductor Michael Tilson Thomas’ job was to make a smoothie.

Esa-Pekka Salonen and the San Francisco Symphony add color and, courtesy of a perfumer at Cartier, scent to Scriabin’s ‘Prometheus.’ Does the novelty prove effective?

In 2018, during Sharon’s three-year stint as artist-collaborator at the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Sharon combined the orchestra’s resources with those of the Industry to mount Cage’s “Europeras 1 & 2,” originally written for Frankfurt Opera in 1987 and meant to deconstruct the full resources of a big opera company. To make it local, Sharon produced his “Europeras 1 & 2” on a Sony Pictures soundstage in Culver City, taking advantage of props and costumes from classic films.

Cage followed “Europeras 1 & 2” with a a pair of chamber operas for an avant-garde theater festival in London. Long Beach Opera is the only company in America to have attempted “Europeras 3 & 4.” A yet smaller-scaled fifth “Europera,” which is well suited for college music departments, gets around more and has been done several times since 2011 at Loyola Marymount University, making the Greater L.A. area the only place in the world where all five “Europeras” have been performed.

The “Europera” essence is the paying attention to what is, rather than belaboring relationships. Cage did not reimagine the past but simply accepted the fact that we are surrounded by old things and old music. There is nothing unusual about hearing an aria in your car and passing a building from another era. Does anyone think it odd to be sitting on a modern sofa while listening to a turntable housed in a 19th century hutch?

In all the “Europeras,” props, costumes, arias and movement, as well as entrances and exits, happen in arbitrary fashion. Singers are on their own. They sing whatever arias they like in the public domain, without regard to anything else around them. The audience is on its own as well. You pick out what you want to hear, see what catches your eye, focus your attention at will. “Europera” is your opera.

A curious L.A. Opera double bill pairs Viennese composer Alexander Zemlinsky’s ‘The Dwarf’ with the Black American composer William Grant Still’s ‘Highway 1, USA.’

“Europera 3” employs six solo singers, two pianists playing tidbits from Liszt opera arrangements and a dozen 78-rpm turntables. “Europera 4” reduces the numbers to a mere pair of singers, a single piano and an antique record player. Sharon raided Detroit Opera’s storage rooms for costumes and props. He scoured local stores for old 78-rpm opera discs and borrowed a Victrola from a patron. The backdrop was a large projection of a digital clock.

Chaos was not the result. Instead, a listener was invited to home in on a forest of opera, noticing this or that — maybe you recognize it, maybe you don’t. But like nature, everything felt like it had a purpose, multiplicity a matter for celebration. The devotion of the six singers mesmerized.

For “Europera 4,” Sharon impressively enticed two stars, mezzo-soprano Susan Graham and bass-baritone Davóne Tines. Each has a stunning, polished stage presence and knows it. Cage might have preferred less showiness, but here they felt bigger than life, capable of moving a listener to tears.

The “Europeras” needed nothing more, but Sharon is a maximalist and pleasingly welcomed into the mix two dancers. Their presence became a reminder of just how much cooperation is needed. “Europeras” are an exercise in social interaction — all elements animate and inanimate, visual and aural, coexisting, each remaining true.

I attended a Friday night performance, the first of three. Sharon attracted the audience every American opera company lusts after, filling the Gem with what appeared to be an eager and open-minded mix of well-dressed opera patrons, new-music fans and curiosity seekers, along with a contingent of out-of-towners not wanting to miss history in the making. Both “Europeras” received excited standing ovations.

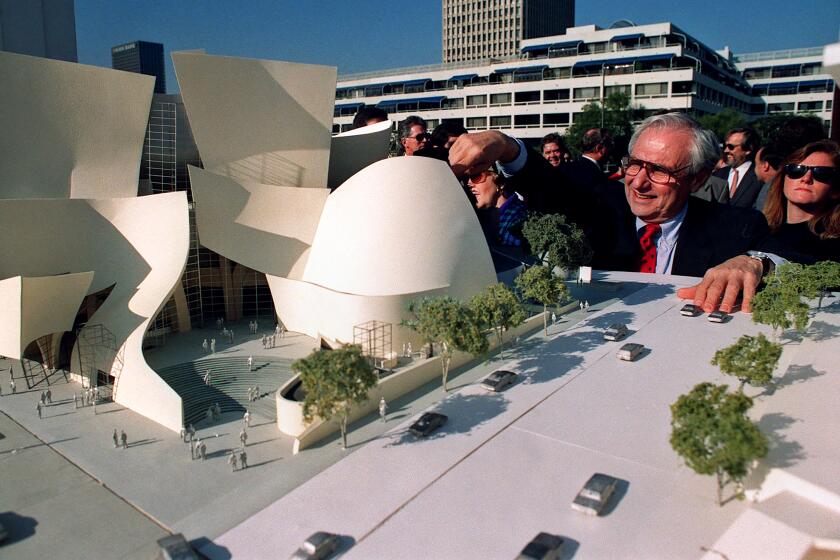

After 20 years, Walt Disney Concert Hall has changed Los Angeles and its philharmonic orchestra, but we now have to live up to Frank Gehry’s full, original vision.

“Europeras” work as well as they do because Cage ingeniously set up strategies that focus our attention on the unexpected. Detroit’s “Europeras” worked as well as they did thanks to Sharon’s genius. He is famously the strategizing mastermind of “Hopscotch,” the 2015 opera staged around downtown L.A. with the audience riding in limos.

So maybe there was some cosmic sense to it all. That same Friday night while “Europeras 3 & 4” were being performed, Lewis, the composer of the upcoming “Comet,” was leading a public discussion with Christian Wolff on the latter’s 90th birthday at Judson Memorial Church in New York. Over more than seven decades, Wolff has been one of the most extraordinary strategist-composers in history. The teenage Wolff astonished Cage when he first studied with him in the early 1950s, becoming the youngest and now final surviving member of Cage’s legendary New York School of composers.

The following evening at Judson an arresting New York ensemble, String Noise, presented a birthday marathon concert at Judson in tribute to Wolff, who, along with being an immutable experimentalist, is a noted classical scholar who had a career as a professor at Harvard University and Dartmouth. His father, Kurt Wolff, was a famed publisher who worked with Kafka, Jung and a great many others.

Along with younger musicians who have avidly and brilliantly taken up Wolff’s music, the marathon included older Wolff colleagues, such as composer David Behrman, who performed on a laptop an incandescent electronic piece, “CW90,” written for the occasion.

Wolff’s music does not, for the most part, look back. It explores possibilities and does so with such rigor and invention that Cage often said he learned more from Wolff than Wolff did from him. The marathon covered the full range, beginning with the first piece Wolff showed Cage, “Duo for Violins,” from 1950. It explores a combination of three pitches. The material for Wolff’s newest score, “What If?,” which had its premiere at the concert, consists of 97 “mostly quite short items for use by from 2 to around 20 performers.” It is up to them to determine what, with whom and when.

Wolff has devoted his life to a study of the ancients. His musical heritage is unequaled by any composer today, in his connection to both the old and the new. And all of that has made him the living, questing embodiment of the musical question: What if? You never know what you’ll get, but I’ve never heard it fail to be arresting at the very least, At their best, Wolff’s what-ifs can be enlightening both sonically and, in the interaction of performers, socially.

In 1997, New York University, a Washington Square neighbor to Judson, published Stuart D. Hobbs’ “The End of the American Avant Garde” as the 37th volume in its “The American Social Experience Series.” The New York School shows up on page 165.

But what if just the opposite of this heedless obituary for the avant-garde is true? What if we are entering a new era led by the likes of Sharon? What if we can utilize history not with the superficial irony of postmodernism but allow the past to be the past — something that is part of us but not holding us back? What if we follow the example of Christian Wolff? That extraordinary weekend suggested we should.

In the meantime, stay tuned for “The Comet/Poppea.” And check out the website of Issue Project Room, the presenter of the Wolff 90th-birthday celebration. Recordings of the conversation with Lewis and the historic marathon concert will be made available once edited.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.