Stephen Sachs documents an American family torn apart by Jan. 6 in his new play

- Share via

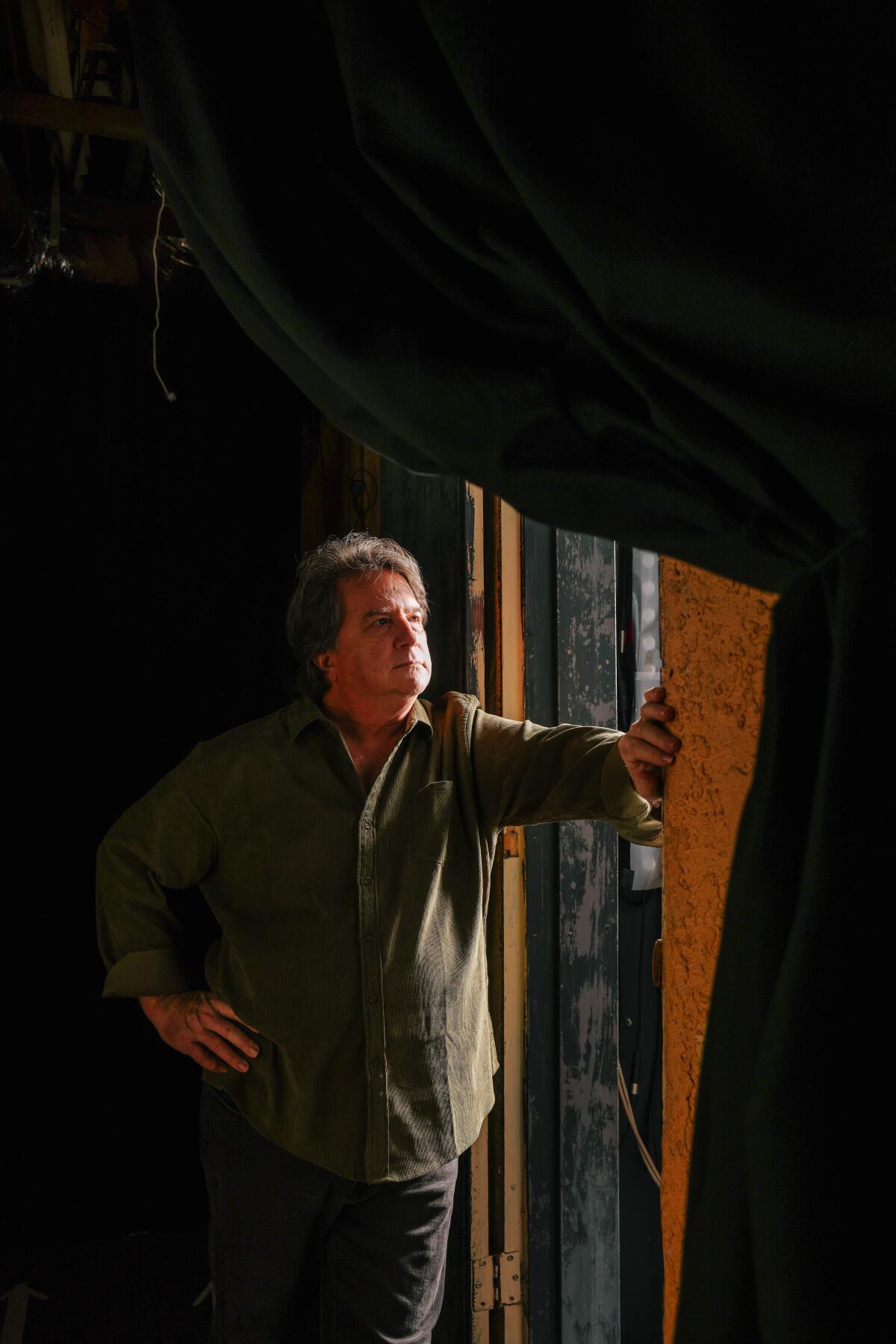

Just before the premiere of his powerful new documentary play, “Fatherland,” Stephen Sachs — co-founder of the Fountain Theatre — announced he would be stepping down as artistic director.

This was a solemn moment for L.A. theater. The Fountain has long been one of the city’s most dynamic intimate theaters, and Sachs has led with tremendous integrity. Leave it to Facebook to misread the moment. The social media site was initially blocking posts about “Fatherland,” including an early rave review that members of the company were trying to share.

Perhaps the play’s title set off algorithmic alarm bells. In any case, this censorship snafu, though soon sorted out, was not what the occasion called for.

“Fatherland,” which is receiving its world premiere at the Fountain, dramatizes through verbatim sources (court testimony, case evidence and public remarks) the story of a family divided by the Jan. 6 insurrection. The case, chronicling a son’s decision to become an informant against his father, has elements of a modern-day Sophoclean tragedy. (The play has been extended through April 29.)

Guy Reffitt was the first defendant to be convicted for his involvement in the Jan. 6 assault on the U.S. Capitol. What separated him from the pack of other insurrectionists was that it was his 19-year-old son, Jackson Reffitt, who tipped off the FBI.

The production, conceived and directed by Sachs, unleashes the power of well-crafted documentary theater. In the role of the father, Ron Bottitta reveals the way conspiracy theories have taken root inside the character’s mind. A set of speeches, unnerving to sit through, unveils the self-fueling nature of true-believer madness.

Security video has documented the insurrection in harrowing detail, but there’s something terrifying in hearing the play-by-play directly from an actor embodying one of the participants. The father’s proudly exuberant messages to his family as he’s storming the Capitol bring the brutality of that day to life. Even those who have closely followed the coverage of Jan. 6 may be horrified anew by the cult-like conviction behind the siege.

Patrick Keleher, who’s making a notable L.A. stage debut, delivers a gripping performance as the son. (Sachs omits names in his nonfiction drama to focus attention on the pattern of a conflict that is at once private and public, domestic and national.) Keleher’s character, a Bernie Sanders supporter who describes himself as “moderately left,” has reason to be disturbed by the transformation of his dad from someone with “moderately right” views to a rabid member of the Three Percenters, a far-right, anti-government militia. Still, he can’t help agonizing over his divided loyalties as citizen and son.

“Fatherland” will leave you shaken. As a work of political theater, it’s a trenchant cautionary tale about the threat posed by extremist groups. As a family drama, it brings the story of America’s polarization into the kitchen, living room and backyard.

Nothing in the play is invented or sensationalized. Certainly, there is no endorsement of hateful ideology. Quite the contrary. The play calls attention to the dangerous reality of right-wing terrorist groups expanding their ranks as once-fringe elements of our society are condoned by irresponsible political leaders, whose partisanship has undermined their fidelity to truth, democracy and the rule of law.

So why then would Facebook have initially blocked posts about a drama that is trying to enlighten the public about what even the Department of Homeland Security acknowledges as one of the gravest threats facing the nation?

According to Sachs, Facebook claimed that the content “does not meet Community Standards” and contains “misleading information.”

The problem was resolved, but it’s a sign of our crackpot times that an intimate theater in Los Angeles with a track record of promoting civil discourse has to contend with the Keystone Kops antics of a tech company that has itself been a hotbed for conspiracy mongers and disinformation campaigns.

It’s enough to make an artistic director throw up a white flag, though Sachs’ decision to retire had nothing to do with this latest contretemps.

“I told the board in August of last year that 2024 would be my last year at the Fountain Theatre,” Sachs said over coffee at a West Hollywood cafe. “The decision was a couple of years coming. I’ve been running the Fountain Theatre for 34 years. That’s a long time. And I’m turning 65 this year. I’ve reached a point in my life where I’m ready to look forward. I’ve been asking myself some fundamental questions. How do I want to spend my remaining years? Do I want to keep producing plays? I’ve decided that 34 years is enough. And I want to spend whatever remaining time I’m blessed with doing other things, particularly writing and traveling.”

The pandemic threw everything into question. Sachs found himself reevaluating what theater meant to him. When the Fountain finally reopened, he discovered that audiences had been doing the same. The old normal was gone for good. Then, the death of two dear colleagues last year, Fountain co-founder Deborah Lawlor, and director Shirley Jo Finney, part of the Fountain’s family of artists, intensified his soul-searching.

“These losses certainly influenced my thinking and helped me come to the realization that now is the time to step away,” Sachs said. “Losing Deborah and then Shirley Jo — Shirley Jo was my director of the heart. She and I were very close. This was a real one-two blow for me, and I began to feel like maybe the universe is telling me something.”

In the note announcing his retirement, Sachs said he’s leaving “the Fountain in its strongest financial position in its 34-year history.” The annual budget, he said, is about $1.2 million, a significant sum for an 80-seat theater in Los Angeles, especially at a time when a great many theaters big and small are hanging on by the skin of their teeth.

Sachs credited Barbara Goodhill, the Fountain’s director of development, with helping to put the theater on solid financial ground. “She’s been a game-changer,” he said. But the Fountain has not been impervious to the storm of post-pandemic challenges.

Audience attrition, the end of governmental emergency support and rising costs have led to a scaling back of programming. “When we first started, you could produce a play for $10,000 to $15,000,” Sachs said. “Now to produce a play in Los Angeles in an intimate theater like mine costs anywhere from $80,000 to $100,000 to do it right. So the numbers have just skyrocketed.”

When I interviewed Sachs in 2015, on the occasion of the Fountain’s 25th anniversary, he spoke openly and ardently about his ambition to expand the theater into a midsize venue in the 150- to 175-seat range. “We could be the Manhattan Theatre Club or Signature Theatre Company of Los Angeles,” he said at the time. “This is an exciting moment of transition in L.A., and I want the Fountain to assume a leadership position.”

“That was the dream,” Sachs said nine years later. “That was the vision. And then COVID happened and the economy dropped. And it no longer became feasible to acquire a bigger building. People were saying to me, ‘What? Are you crazy? You own your own property. You know how rare that is?’ And then I remembered Athol Fugard telling me that bigger does not always mean better.”

Fugard, the South African playwright who was a leading artistic voice in the protest movement against apartheid, developed a relationship with the Fountain after being impressed by Sachs’ production of “The Road to Mecca” in 2000. The Fountain became the Los Angeles home for the playwright, who entrusted the theater with many of his late works, including “Exits and Entrances,” which had its world premiere at the Fountain in 2004, and “The Painted Rocks at Revolver Creek,” which had its U.S. premiere there in 2015.

Sachs included the Fugard productions in his list of career highlights. During his tenure at the Fountain, he produced work by some of the boldest American playwrights writing today, including Tarell Alvin McCraney, Stephen Adly Guirgis, Martyna Majok and Branden Jacobs-Jenkins.

Although at a disadvantage in securing the rights of critically acclaimed new works as a smaller theater, the Fountain established such a courageous reputation that artists began to see it as a point of honor to have their plays performed there. The Mark Taper Forum’s timidity turned into the Fountain’s opportunity.

But Sachs was eager to talk about a different source of pride. In looking back at his accomplishments, he singled out the Fountain’s role in helping to launch Deaf West Theatre.

“The first three productions of Deaf West were at the Fountain,” he said. “I directed the second production, ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,’ with a deaf and hearing company. It was an exciting time because no one was doing it. When deaf audiences came to the Fountain, they would see a play performed in their language. And to see the looks on their faces, it was just so rewarding. And then I began to write plays for deaf audiences. I wrote ‘Sweet Nothing in My Ear,’ which was about cochlear implants. And that was made into a TV movie with Marlee Matlin and Jeff Daniels.”

Sachs has been a prolific playwright. “Bakersfield Mist,” one of his most successful works, ran for seven months at the Fountain before receiving a production in London’s West End starring Kathleen Turner. But he said he’s not leaving the Fountain to be a full-time dramatist. He’s been working on a novel, a work of historical fiction, and said that, having written 18 plays, he’s officially turned his keyboard over to another branch of literature.

But substantive drama is still at the heart of the Fountain’s identity. The theater’s mission — to “develop provocative new works or explore a unique vision of established plays that reflect the immediate concerns and cultural diversity of contemporary Los Angeles and the nation,” as elaborated on the company’s website — hasn’t changed.

Theatergoers in general have been more reluctant since the pandemic to take a chance on a new play or a revival of a classic without a big-name celebrity in the cast. Has the Fountain confronted such headwinds? Sachs acknowledged that “it has been a slow return” but that his audience has been coming back.

Loyalty is earned, and the Fountain has one of the most faithful audiences in town, thanks in no small measure to Sachs’ grassroots leadership. Boards of directors may disagree, but artistic integrity is still the best long-term strategy for nonprofit theater success.

” I look around and I see what’s being produced in Los Angeles and across the country,” Sachs said. “And I understand how programming has swayed more toward popular fare and the need to do musicals. I’ve also heard that people don’t want to be preached to, that they want to be uplifted and made to feel good. I’m as much of a fan of good comedy as anybody else. But it’s essential to me that the Fountain Theatre does not sell its soul. There is still an audience out there for serious, meaningful theater.”

Sachs joked that the Fountain is like the Corleone family — “you can never leave.” “Actors, designers, directors have worked with us for decades,” he said. (“Some theater companies have a staff turnover problem. We have the opposite issue,” he wrote in a follow-up email.) But he vows, as a national search gets underway for his replacement, that he won’t be one of those founding artistic directors micromanaging their successor from the wings.

His work at the Fountain is nearly done. But he’s still fighting the good fight. “Fatherland,” written in a white heat for this election season, is defending democracy from the stage. Facebook might not get it, but L.A. theater audiences thankfully still do.

Kristen Adele Calhoun’s haunting “Black Cypress Bayou” wrestles with history and reparations in its world premiere at the Geffen Playhouse’s Audrey Skirball Kenis Theater.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.