Chicana feminist Judithe Hernández draws complex humanity at the Cheech

- Share via

In a revealing video interview that accompanies her captivating 50-year survey at the Riverside Art Museum’s Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture, artist Judithe Hernández recounts how she became the anomalous fifth member of Los Four, the groundbreaking L.A. art collective. Following the group’s ambitious 1974 exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Hernández prevailed upon them to admit her into their ranks.

An activist colleague and friend of Los Four’s Frank Romero, Beto de la Rocha, Gilbert “Magú” Luján and, especially, Carlos Almaraz, the painter with whom she had been among just five Chicano students at Otis Art Institute (now Otis College of Art & Design), she pressed an irrefutable point: Being all male, Los Four was inherently compromised in its insistence on full Chicano equality in American life. Hernández provided them with a portfolio of her work, so Los Four could see that it was artistically satisfactory.

Lotería is to the pastel drawings of Judithe Hernández what the I Ching was to John Cage’s avant-garde music after World War II or the “Three Standard Stoppages” were to the Dada objects of Marcel Duchamp a century ago.

“She draws like a man,” Los Four approvingly decided, happily accepting her entreaty to join the group. Hernández, in a deadpan recounting of that rationale in the video, offers up an affectionate and knowing smile.

The wry anecdote underscores two qualities of her work that run throughout “Judithe Hernández: Beyond Myself, Somewhere, I Wait for My Arrival” at the Cheech. First, a feminist framework structures everything. Second, drawing is fundamental. The exhibition demonstrates, as if proof were needed, that social activism and individual artistic freedom are anything but incompatible.

In more than 80 drawings and several sketchbooks, which date from the 1970s to the present, women are almost always pictured. Men turn up in just a tiny handful — a 2010 series on the Christian origin story of Adam and Eve — but only to clarify the structural foundations of routine, often unacknowledged chauvinism.

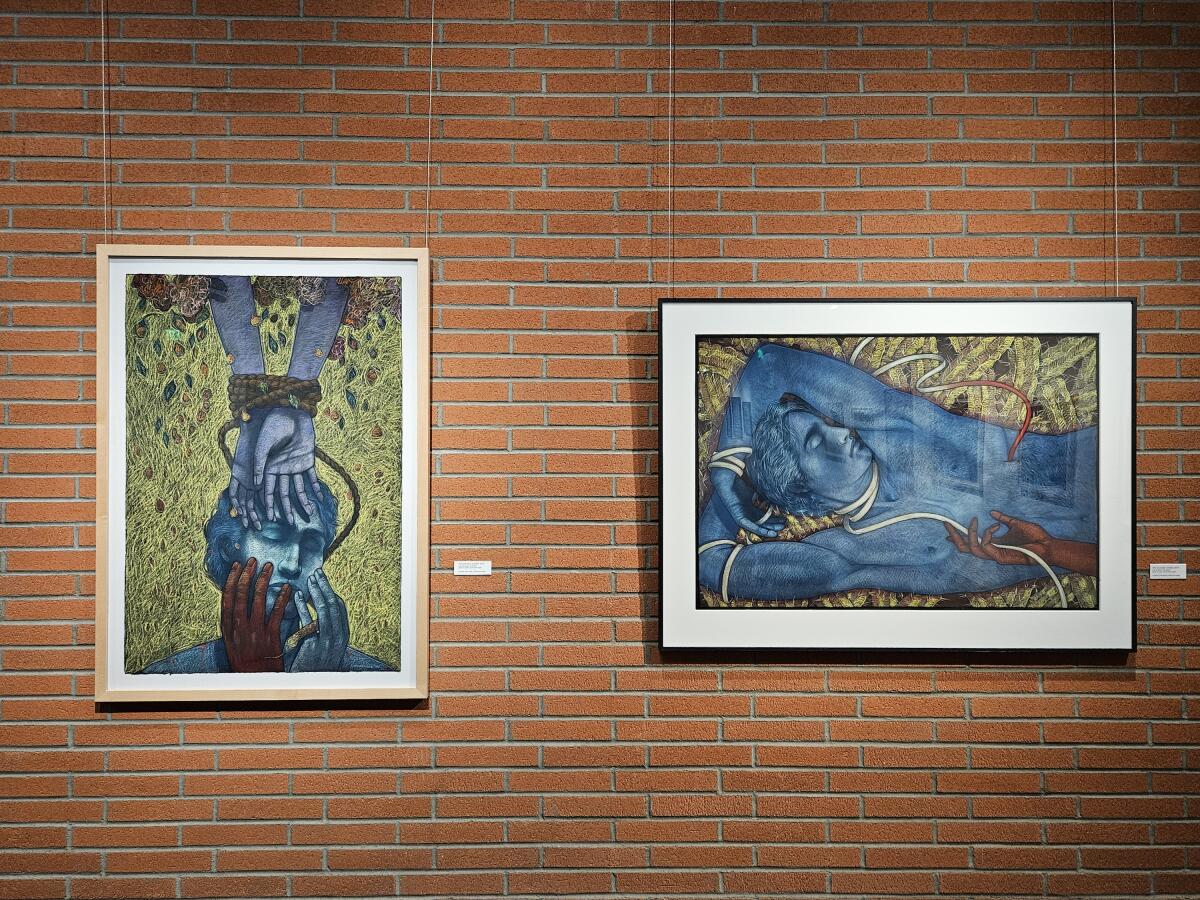

She renders Adam as a veritable boy-toy, handsome and naked, like a Madison Avenue model picked to sell cologne. Hernández often employs iconic compositions for her work, with just one or two figures shown frontally or in profile and located in a shallow, often decorative space. In “The Surrender of Adam,” the first man reclines naked in a tangle of deep green vegetation, Eden now a knot of San Pedro cactus.

In “The Birth of Adam,” he lies on a ground strewn with pebbles and lily pads, born of the soil that gave him his name (the Hebrew adamah). His eyes are shut, a flower pressed against his chest. His skin is blue, at once chilly but also the color of divine favor, from Hinduism’s Vishnu to Christianity’s mantle for the Virgin Mary.

Art in ‘Land of Milk and Honey,’ a lively, engaging and sometimes sobering group exhibition at the Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art and Culture, casts a skeptical eye on California agriculture.

“The Beginning of Sin” shows Adam from behind lying stock-still on top of Eve, his arms spread wide across the page and beyond its edges, in what can only be described as a prophecy of crucifixion. With her arms wrapped around him, she wears the mask of a luchador — a theatrical Mexican professional wrestler — crowned with branching horns. It’s like Frida Kahlo’s self-portrait as a wounded deer but without any injurious arrows to be seen. This Eve is robust, not distressed. She’s no martyr.

Lying on her back, she stares straight past Adam’s adjacent head and into the viewer’s eyes, wholly indifferent to the deadly red-and-black striped coral snake slithering nearby. Her lips are as crimson as the demonic serpent. Hernández is a brilliant colorist, the vivid hues sometimes functioning in suggestive symbolic mode while always reveling in pure decorative joy.

The decorative element is as feminist as her subject. For whatever reason, a pejorative implication always shrouded decoration in the modern era — even around such an important artist as Matisse. (It’s one reason Matisse was foolishly regarded for so long as secondary to Picasso.) But not here. Hernández, like other artists as different from her and from one another as Valerie Jaudon and Merion Estes, empowers decoration in the service of empowering women. She remade the Genesis story into a colorful visual narrative of complex humanity, rather than a fall from grace.

Hernández was born in Los Angeles in 1948. At 22, her arrival at Otis coincided with the 1970 Chicano Moratorium, the huge antiwar demonstration in East L.A. that forged a broad-based coalition of Mexican American groups in opposition to the Vietnam conflict. Her mentor at Otis was Charles White, the esteemed Black artist whose 1946 study with David Alfaro Siqueiros and Diego Rivera at Mexico City’s Taller de Gráfica Popular (the People’s Print Workshop) cemented his commitment to socially and politically conscious graphic art.

The exhibition, organized by the museum’s artistic director, María Esther Fernández, is divided into four loosely thematic sections, rather than unfolding in a strict chronology. “The Evolution of the Female Archetype” is the closest to providing background — unfortunately, publication of a reference catalog is not expected until the fall — with observant if generally uninspiring genre scenes of humdrum daily life.

Next comes “Ni una más: Bearing Witness,” which gets up to speed fast. The section emphasizes work related to the shocking serial murders of women in and around the Mexican border city of Juarez, which has seen bloodshed for more than 30 years. (Appropriately, in September the Hernández survey will travel to the El Paso Museum of Art, just across the border from Juarez.) “Reimagining Eve” then pictures women as something other than subordinates — forget about Adam’s rib — while a final gallery marked by hallucinatory and dreamlike probing looks at the “Surrealist Landscape” as a dominant psychic, sociocultural context for Hernández. The organization works well.

Hers is a world where logic does not reign, independence is essential and the unconscious is a mechanism for self-knowledge. Mysterious outside forces are evoked by a red hand that, in numerous works, intrudes on the scene from the picture’s edge. The fateful hand reaches toward Eve on her final night before expulsion from the garden, for example, and elsewhere wields a knife blade to cut a flower rising from the sea next to a floating body.

One lush drawing shows a woman sleeping on the ground before a formidable wall of prickly pear cactus, an entangled piñata floating above like a tantalizing, delight-filled dream that is just out of reach. In the United States, California has always held promises of self-reinvention, and Hernández brings Chicana feminism into the enterprise.

Mexican mysticism, inflected by pre-Columbian and Catholic cultures, informs much of the work. Most notably, the young woman standing before a hot pink wall in the coming-of-age icon “Juarez Quinceanera” sports enormous Aztec spools in her ears. The spools frame her mask-like open mouth, decorating voids in the human skull that signaled the soul’s vivacity in pre-Columbian culture. She’s crowned with an elaborate, off-kilter sculptural headdress reminiscent of the dragon-like feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl, the creator deity. A pair of calla lilies grasped in her hands acknowledges fertility.

Yet amid all the elaborate cultural festivity around the girl’s arrival at womanhood, there’s a sobering catch. White is the traditional color for an extravagant quinceanera dress, but hers is a funeral black. Behind her she casts a looming dark shadow against the bright pink wall. The fateful red hand that intrudes into other works here smears blood on that wall, as if left behind by a slumping body. For “Juarez Quinceanera,” life and death collide and intertwine.

L.A. artist Joey Terrill’s vibrant canvases, on view at Marc Selwyn Fine Art, chronicle intimate moments of queer Chicano life: heartbreak and love and life with HIV.

What makes this and many other Hernández works especially compelling is their medium. These are drawings. The show surveys pastels, their details sometimes inflected with colored pencil, meticulously drawn on large sheets of paper or canvas. Hernández gives her drawings a scale more commonly encountered in easel paintings, but the form is marked by a visual intimacy different from paint applied with a brush. Drawing is about touch, the hand pressed directly to the sheet. Touch holds your eye, inviting close scrutiny.

Hernández is often referred to as a painter, and she has in fact painted numerous public murals. Yet, like her late mentor Charles White, drawing represents her most powerful gift. The urgency of her subject matter is given voice. Hernández doesn’t draw like a man; she draws like an important artist.

'Judithe Hernández: Beyond Myself, Somewhere, I Wait for My Arrival'

Where: The Cheech Marin Center at the Riverside Art Museum, 3581 Mission Inn Ave., Riverside

When: Through Aug. 4. 10 a.m.–5 p.m. Wednesday-Saturday. 12 p.m.–5 p.m. Sunday

Info: (951) 684-7111, www.riversideartmuseum.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.