- Share via

New York — The first concert I saw after the pandemic lockdowns was a recital staged by the Youth Orchestra Los Angeles in May 2021. Two dozen masked teens performed a Bach concerto to a handful of music and design writers as a socially distanced acoustic test of YOLA’s new home: an old bank building in Inglewood that had been transformed into a concert and rehearsal space by Gehry Partners. The performance was short — more rehearsal than recital — but it remains one of the most memorable I’ve been to. There was a crackle of energy from the presence of chattering bodies in a room and the warm cacophony of string musicians tuning instruments.

“This is my first indoor concert in 15 months,” I jotted in my notepad that day. If I weren’t a Scorpio, I might have cried.

COVID-19 not only shut us in our homes, it intensified our use of architecture and technologies, like drive-throughs and mobile ordering, that circumvent the casual interactions that act as social glue. A fascinating story published by Linda Poon in Bloomberg CityLab earlier this month looks at how the elimination of these trivial-seeming encounters in spaces designed for maximum efficiency has helped contribute to a “loneliness epidemic.” Live performance is therefore a precious experience: the collective gasp, the pin-drop silence, the ebullience of shared laughter and applause.

Two venues in New York City — the new Perelman Performing Arts Center in Lower Manhattan and the revamped David Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center — had me thinking about how design brings people together in performing arts spaces. Both the Geffen and the Perelman mark a move away from fixed proscenium arch stages, a form with roots in the Italian Renaissance that puts performers at a remove from the audience. Instead, both halls feature more flexible settings in which viewers can encircle or be immersed in the action.

“It’s the idea that we are together with the artist,” says architect Gary McCluskie of Diamond Schmitt, the firm that reimagined the auditorium at Geffen Hall. “As an audience, we are making this together. The thing doesn’t exist without the audience.”

Smart adaptive reuse reimagines an old bank as a musical performance site for Gustavo Dudamel’s YOLA, in the process preserving a piece of Inglewood.

An infernally complicated site

Togetherness doesn’t necessarily come easily.

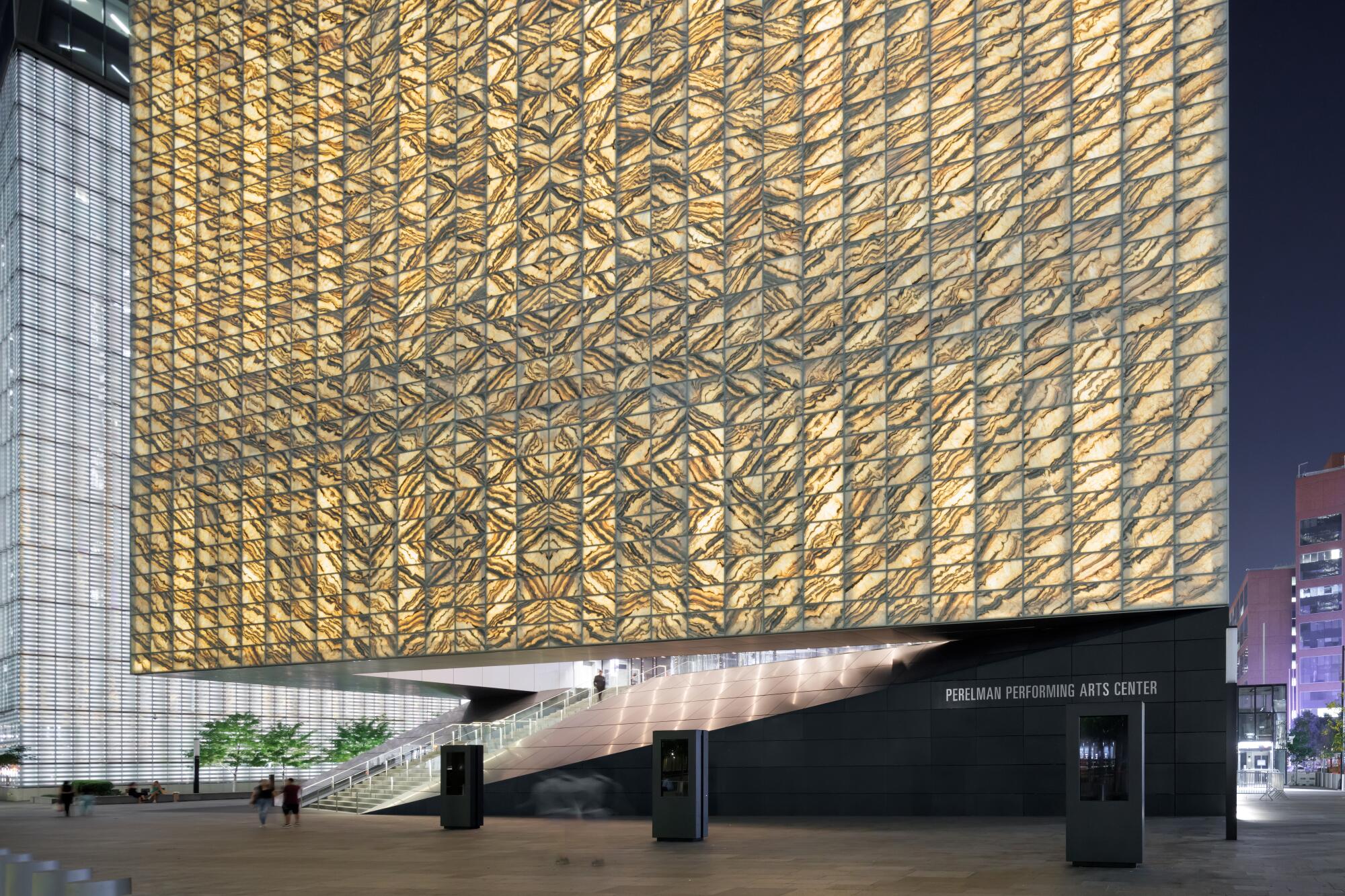

The $500-million Perelman, which opened its doors in September, is the cultural component in long-running redevelopment plans for the World Trade Center site in Lower Manhattan, which was leveled by the attacks of Sept. 11. The building was designed by Rex, the New York-based studio founded by Joshua Ramus (a former partner at Rem Koolhaas’s OMA), and lobby and restaurant interiors were conceived by David Rockwell of the Rockwell Group, the firm behind the fabulous deco aesthetic of the 2021 Academy Awards at L.A.’s Union Station. Serving as executive architect was Davis Brody Bond.

Both Ramus and Rockwell lived in neighboring Tribeca during 9/11. “When the towers came down,” Ramus recalled during a walking tour of the Perelman, “it blew the windows out of my apartment.” Rockwell was part of a team of artists and designers who helped make a home for an elementary school displaced by the attacks, and he helped create a viewing platform for the public to witness recovery work at the site. For both, working on the Perelman has been personally meaningful.

But it was a two-decade haul to get here. Cultural groups came on board the project, then quickly got off. Frank Gehry was supposed to design the building — until he wasn’t. Funding remained a mirage until Ronald O. Perelman and, later, Michael Bloomberg (who serves as board chair) stepped in with donations of $75 million and $130 million, respectively. And there’s the question of site, which is — to put mildly — infernally complicated.

For starters, there’s everything around the Perelman: office towers from the Make-It-Blast-Proof School of Architecture; Santiago Calatrava’s mystifying winged transit hub; the sunken pools of the 9/11 Memorial, designed by Michael Arad, with landscape by Peter Walker. (A lot of dude.) As critic Karrie Jacobs wrote of the area in a recent issue of the New York Review of Architecture, “this place hasn’t coalesced into a New York City neighborhood. It is still a ‘site.’”

There is also the land on which the Perelman sits. Owned by the Port Authority, it is stuffed with several stories of infrastructure, including two train lines and loading dock access for the entire World Trade Center — not an optimal place for a theater (and requiring heroic work of the engineers at Magnusson Klemencic Associates). The venue sits 21 feet above grade; reaching the lobby requires a trip in an elevator or a trot up a flight of stairs. Moreover, a requirement of the site was that commercial activity not be visible from the 9/11 Memorial across the street, which means that the Perelman’s on-site restaurant and its box office are tucked away.

As a result, the building is not exactly a paean to openness. Its cubic form and Portuguese marble facade are inscrutable — a “mystery box,” Ramus calls it. During the day (especially a cloudy one), the marble is hard and mute. At night, however, when the building is lit from within, it takes on a lantern effect, illuminating the striations in the stone, which are laid out in a symmetrical pattern evoking the grain of a textile. The marble, says Ramus, “is quiet during the day when the memorial is at its most active, then it comes on as the city gets dark.”

From inside, the sun shining through the marble creates a luminous effect, though it is disorienting given the lack of windows. It can also feel chilly — something that Rockwell has countered with his interior design for the lobby and restaurant, which is rendered in the warm tones of wood and clay. He has also wrapped some of the walls with stacked felt to prevent the environment from becoming cacophonous. A series of illuminated ribs on the ceiling connect one space to the next and are visible from the street, indicating that there is life in this building.

Indeed, tucked into the lobby is a free, cabaret-sized performance space — which was jammed, the night I attended, for a gig by jazz vocalist Vuyo Sotashe and pianist Chris Pattishall.

The most interesting parts of the Perelman, however, are the theaters: three of them laid out in an L, flexible spaces that can be configured into one theater or two or three with more than 60 different seating formats. Directors can arrange a proscenium stage, an open black box space or a theater in the round — along with every possible permutation in between. Mechanical walls can be lowered and raised, balconies can be shifted and the rake of the floor adjusted thanks to a mind-boggling mechanical apparatus below. (An animation on Rex’s website provides a good overview.)

Last month, I saw a production of “Watch Night,” a multidisciplinary work by choreographer Bill T. Jones and poet and playwright Marc Bamuthi Joseph, which examined the violence at the root of two mass shootings — one in a synagogue, the other in a Black church. The stage was laid out transverse style, so that the audience flanked the presentation on two sides. Actors materialized on balconies overhead and prowled the aisles between seats. Sometimes, the action lay before us; at other times, behind.

The shifting positions demanded attention; they also implicated us all in this brutal story. My husband sat across the stage from me and was visible during a climactic scene in the work. We weren’t sitting in a dark room observing “Watch Night” from a distance. We were in it.

‘Sweet Land’ by Yuval Sharon’s the Industry, was being performed at Los Angeles State Historic Park until it was cut short due to the coronavirus.

A much-belated renovation

A sense of immediacy is likewise present in Lincoln Center’s renovated David Geffen Hall, completed late last year. The $550-million project was another that was a long time coming — back to 1962, when the building first opened and it became clear that the acoustics were terrible. A 1976 renovation by Johnson/Burgee — when the hall was renamed for Avery Fisher — improved the sound, but didn’t fix it.

In 2015, David Geffen (who is fond of emblazoning his name on architecture) donated $100 million in anticipation of another renovation. On this go-around, the firms tasked with hitting the reset button were Diamond Schmitt, the Toronto-based architectural firm behind the Maison Symphonique in Montreal, and Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects (TWBTA), the New York City-based studio that is currently at work on the Obama Presidential Center in Chicago. Diamond Schmitt worked on the design of the auditorium and back-of-house spaces; TWBTA focused on public areas.

Like L.A.’s Music Center, Lincoln Center was designed in a ‘60s-era temple-on-a-hill mode, giving a cold shoulder to the city around it. Both were built in neighborhoods inhabited by people of color that were razed during a midcentury frenzy for urban renewal. Both were designed as Modernist interpretations of Classical temples: the Geffen by Max Abramovitz, the Music Center by Welton Becket. And both feel out of date at a time when there is talk of greater equity in urban design.

“This building from the ‘60s,” says TWBTA architect John Skillern, “was not designed with the future in mind.”

The Los Angeles Music Center will unveil its $41 million plaza revamp by Rios Clementi Hale Studios on Aug. 28. The project is meant to connect the cultural complex with Grand Park.

TWBTA has made a number of moves to open up the Geffen to the city around it. The lobby — which once had all the charm of a bank branch — has been remade into a welcoming public lounge with a garage-style door that opens to the plaza when the weather is mild. An office that ate up part of the ground level has been reconfigured as a small performance space that is visible from the street. At night, the building is illuminated to reveal all the activity taking place within.

Most pleasingly, TWBTA has done away with the tedious palette of beige on beige that previously defined the public spaces. Instead, the walls on each floor are now lined with a custom felt textile bearing images of rose petals floating against a background of sapphire blue (a pattern also employed on the auditorium’s seats). And the open staircases linking one floor to another have been covered in glimmering Orsoni tiles from Italy. The effect is lightly glamorous.

Both architectural teams have also made numerous improvements related to accessibility, adding more elevators and a sequence of ramps connecting to every tier of the auditorium.

And, ultimately, this building is all about its auditorium.

Diamond Schmitt essentially tore the insides out and started over. The room is now lighter and brighter, with walls sheathed in rippling beech wood and the stage clad in white oak. Like the Perelman, the stage is flexible — powered by 22 lifts that accommodate an array of performance types, including pop concerts, semi-staged operas and solo shows in addition to the regular orchestral concerts. Most significantly, the proscenium arch is gone. The stage has been brought forward and it is now surrounded on all sides by seating, inspired by the “vineyard-style” plans of venues such as the Berlin Philharmonie and L.A.’s Walt Disney Concert Hall.

The seating has also been vastly improved: Balcony seats have been arranged at more comfortable angles and the architects have steepened the rake of the auditorium at orchestra level, allowing for improved sightlines — critical for a shorty like me. (Years ago, I attended a concert here by mambo pioneer Israel “Cachao” López and all I could see was the pomaded head of the man in front of me.)

Natural history museums have fraught histories. Studio Gang has designed a building that takes the concept out of the 19th century and brings it back to nature

David Geffen Hall feels far less stuffy than the Avery Fisher Hall of my memories. The bright blond wood begs for a comfortable sweater rather than a beaded gown. And the space is vastly more intimate. I saw violinist Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider play Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D Major with the New York Philharmonic in early November and was struck by how the reconfiguration of the hall, along with greater illumination, made the audience a part of the proceedings — the man who bobbed his head in time with the timpani, the woman in the red shawl who enthusiastically applauded the musicians.

I am not a sound expert and can’t speak to the building’s acoustics. (The reviews have been mixed.) But at a time when so many hours of our day are spent passively watching screens, the shared experience of a roomful of people sitting in a circle listening to music felt like a hopeful, regenerative act.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.