Review: James Castle made thousands of resolute drawings with soot and spit

- Share via

SANTA BARBARA — James Castle was obsessed with drawing. He reportedly drew at least one picture every day, and often many more, which added up to a portfolio of thousands when the self-taught artist died in 1977 at the age of 78.

Most are very small, just several inches on a side. And the medium he most often employed is unlike any other. On found scraps of paper and cardboard — flattened cigarette packages, file cards, envelopes, matchboxes and the like — Castle used small, sharpened sticks and cotton swabs to draw with black soot scraped from a wood stove and mixed with spit. The look that resulted is oddly soft but dense, brimming with visual tactility, the paper beneath often assuming a spongy glow.

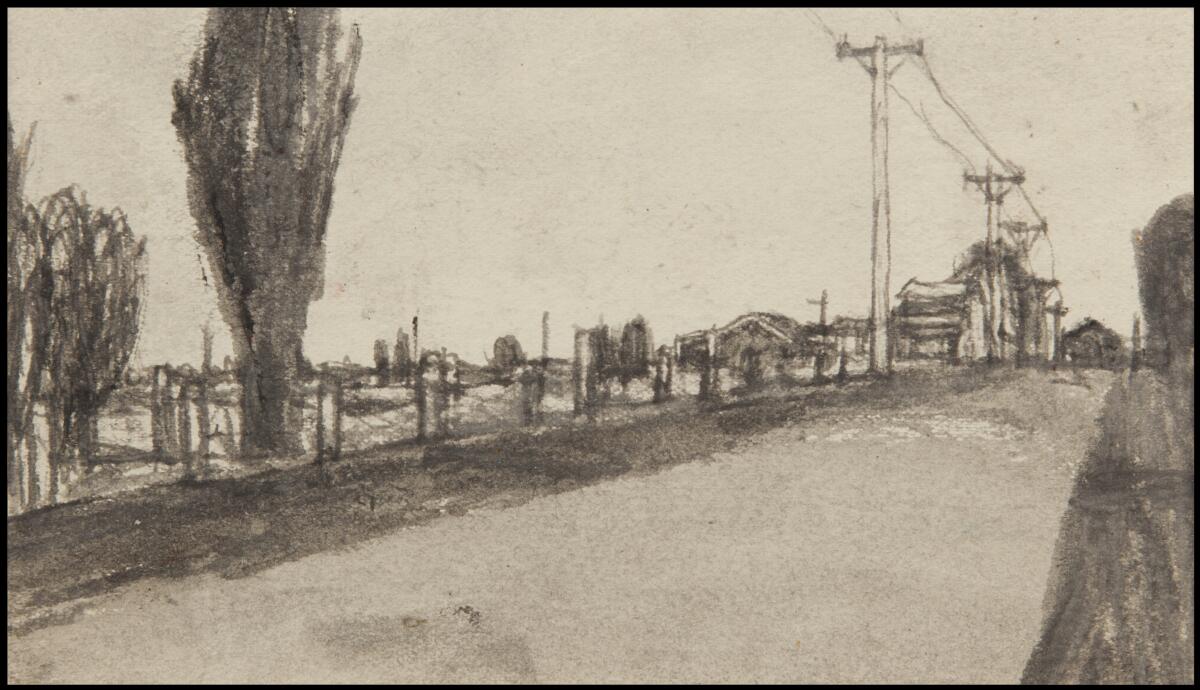

Once a mark of soot was made it could not be undone, so it was left alone or, if it needed fixing, melded into more marks. Castle’s style is additive, not subtractive. A heaviness attends images of the fields around the farmhouse where he lived for a time in rural Idaho, or the unpopulated rooms of the family home outside Boise where he moved when he was in his 20s. (He never left Idaho.) The modest scale of the drawings, where any dimension more than 10 inches is a rarity, while three or six inches is common, generates a focused intensity.

At the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, a modest selection of 86 drawings (12 of them double-sided sheets), two sketchbooks and three puppet-like constructions of cardboard wrapped in paper and twine offer a good introduction to Castle’s curious and compelling body of work. “The Private Universe of James Castle,” which will not travel, was organized by the museum’s director, Larry J. Feinberg, who retires in October after 15 years in the post.

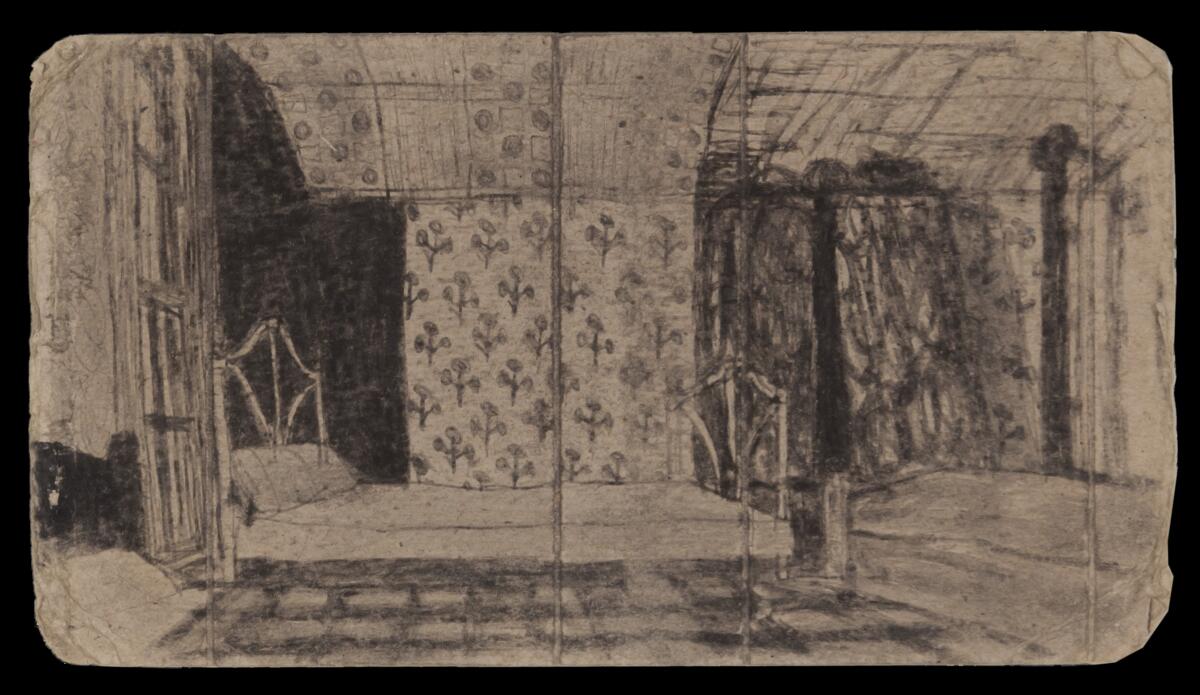

What soon becomes evident is the degree to which patterning is a critical element in Castle’s drawings. The fence-lined roadway of a landscape is marked by a rhythmic line of fence posts and telephone poles receding into deep space. Beekeeper boxes in a field are stacked to impossible heights, towers seven or eight boxes high, like a farmer’s version of Brancusi’s “Endless Column” or a modern city skyline. The wood-slat walls of a big chicken coop that for a while served as Castle’s makeshift studio merge into wood flooring and paneled furniture, creating a linear environment of stripes. Floral wallpaper climbs to a bedroom ceiling to be replaced by an array of polka dots and descends to the floor to become plaid.

In one arresting work, attic wainscoting is a series of vertical black rectangles lined up one after the next against grayed ground. The drawing, virtually abstract, looks for all the world like a mid-1960s Post-minimal rendering by Eva Hesse.

Pattern is repetition. Repetition is ritual. Castle’s drawing is a kind of secular daily custom. As with any ritual, he asserts his presence in the world, creates a place to be, opens a space for contemplation and celebrates his own engagement.

The little-known Italian Baroque painter’s approach bestowed an aura of dignified understanding usually reserved for the upper classes onto people who were down and out.

Castle was born in the tiny mountain village of Garden Valley — and I mean tiny, maybe 25 people — about 50 miles north of Boise, in 1899. He was profoundly deaf. As a child he spent about five years at Gooding School for the Deaf and the Blind, but there is no evidence that he learned to read, write, speak or use a conventional sign language. Think of his drawings as his own sign-language invention — a way to visually speak of his experience.

The school seems to be where he began to draw, although nothing apparently remains from the time. His family was supportive, and he kept it up when he returned home. Drawing remained a private pursuit for the next four decades, when Castle began to have a few exhibitions at Pacific Northwest schools and art centers. By the time of his death, art by untrained artists had gained widespread cultural currency, and his drawings began to be shown in larger venues.

Since 2000 his work has been seen everywhere from the Drawing Center in New York to Madrid’s Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. A full retrospective was assembled by the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2009, featuring more than 300 examples; it traveled to Chicago and Berkeley.

The Santa Barbara show is Southern California’s first, and for it, Feinberg has taken a focused approach. Although Castle made works with color, utilizing a variety of materials that include laundry bluing, watercolor, crayon and even colored ink leached from magazine pages, these are black soot-and-spit. (The museum discreetly uses “wash” rather than saliva as descriptor.) His subjects also included typography, calendars, animals, product brands, comic strips — “Henry,” the mute bald-boy drawn by Carl Thomas Anderson beginning in 1932, was (perhaps tellingly) a favorite — and more; but landscapes and domestic interiors dominate here.

None of the works are dated, so no firm chronology is possible. Castle is known to have worked from memory, too, so connecting a drawing of stacked beekeeper boxes in a farm scene or an extravagantly wallpapered bedroom to a particular time and place of residence doesn’t quite work. (“James Castle: Memory Palace,” a 2021 book by critic John Beardsley, identifies the operations of remembrance frequently at work.) The correct sequence of drawings over 60 years or so will probably never be unraveled, and judging from the selection here, it might not matter much. There aren’t any noticeably dramatic shifts in style or subject. The ritual persists.

Maybe some drawings — especially the chambered spaces of domestic interiors, which can be quite complex — are more sophisticated than others in the subtlety of execution, suggesting skill developed over time. But rarely is it possible to tell for sure. More significant is the recurrent emphasis on patterning.

Like the hugely successful early 20th century L.A. landscape painter Granville Redmond, who was also deaf, Castle is sometimes claimed to have compensated for his hearing loss through an increased power in visual acuity. Feinberg rightly sets that erroneous interpretation aside. Art is not mechanistic. Castle drew well because he was a gifted artist, not because he was making up for a physical disability.

Memory, however, does seem unusually resonant in terms of the artist’s favored material. Soot from a wood stove is residue. Like a memory, it’s what’s left after the fire has died down. In their ritual performance, so are Castle’s resolute drawings.

'The Private Universe of James Castle'

Where: Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1130 State St., Santa Barbara

When: Tuesdays - Sundays 11 am - 5 pm, Thursdays 11 am - 8 pm. Closed Mondays. Through September 17.

Info: www.sbma.net, (805) 963-4364

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.