- Share via

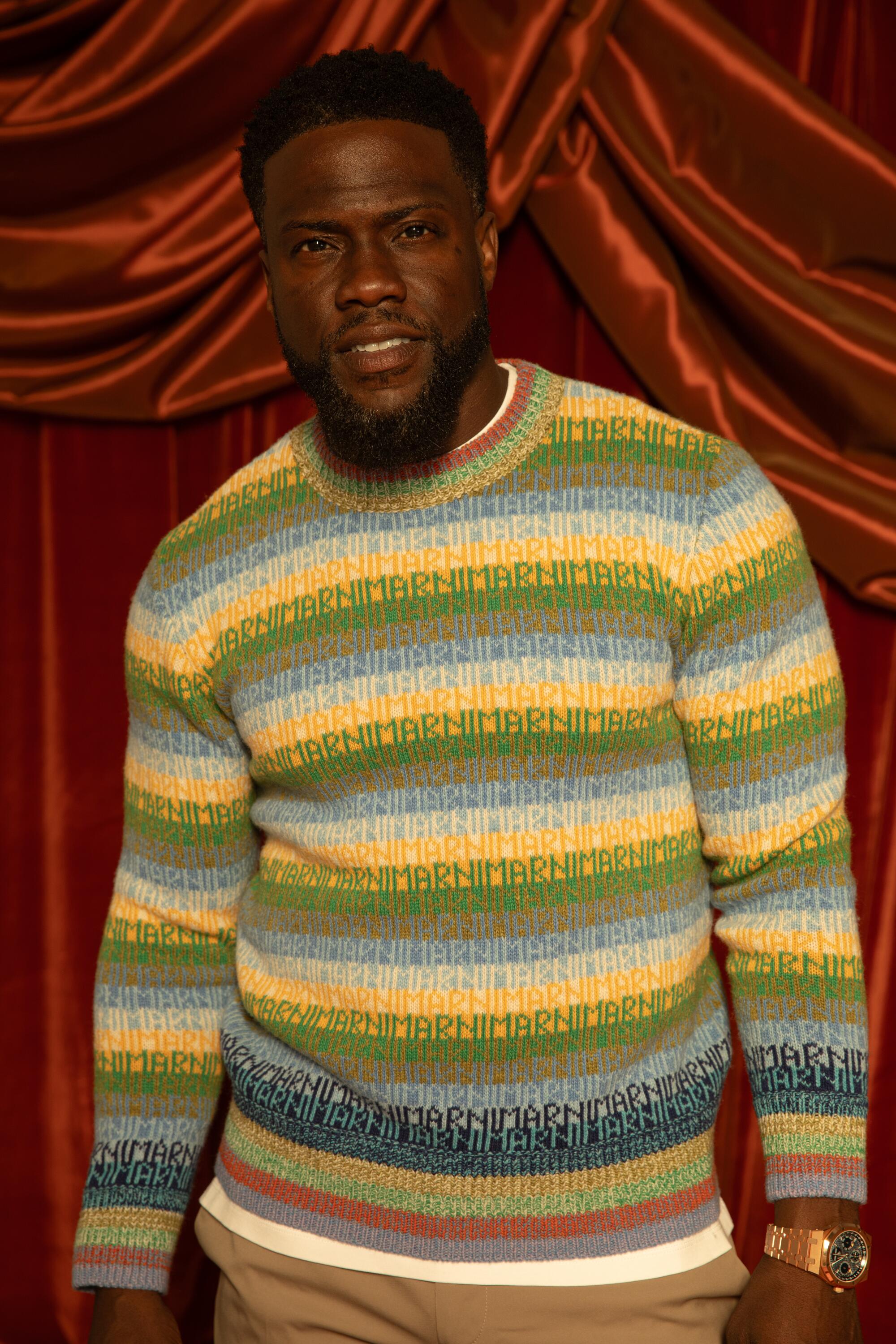

Kevin Hart wet the bed last night.

For the record:

9:21 p.m. July 30, 2023An earlier version of this story stated that Hartbeat Weekend was underwritten by Kevin Hart; it was underwritten by his company Hartbeat Ventures.

He had spent his 44th birthday slamming back shots of tequila and partying with Ludacris at a nightclub until 4 a.m. A few hours later, he awoke in his palatial Las Vegas hotel suite and asked his wife who had thrown water on his side of the mattress. She suggested that it was in fact he who had soiled the linens.

“And I’ll be damned,” Hart says.

He’s still in Vegas, recounting the incident to five of his closest friends. Plus a live audience of 100 or so at a sports bar, where the group is recording a live version of their weekly podcast, “Straight From the Hart,” which airs on the comedian’s SiriusXM channel.

Who are the people shaping our culture? In her column, Amy Kaufman examines the lives of icons, underdogs and rising stars to find out — “For Real.”

“You know,” one of Hart’s buddies says, “there is such a thing as being too honest.”

“I have no problem being honest,” Hart fires back. “That’s the thing that people are afraid to do in these times.”

Presumably, this is why he is allowing a journalist to shadow him during Hartbeat Weekend, a four-day, alcohol-fueled extravaganza highlighting the many facets of Kevin Hart.

Headquartered at Vegas’ Resorts World, the July 6-9 gathering is a mini-festival with 19 events curated by the comedian and underwritten by his company, Hartbeat Ventures. There will be performances from his favorite acts (Jack Harlow, T.I., J. Cole), pool parties, the inaugural taping of a relaunch of BET’s iconic “ComicView” — which his Hartbeat company is behind — and a couple of shows by Hart himself. Attended by about 50,000 fans — who pay for one-off tickets to most of the events — it is an attempt to synthesize the various entities under the umbrella of Hart’s rapidly expanding business ecosystem.

Ostensibly, that’s why I’m here. Not to witness Hart drink until he blacks out — which will occur — but to observe his self-described transition from celebrity to brand.

It’s been a complex journey. There was a time, according to his friends, when Hart kept much of his wealth in cash because he feared the stock market was a Ponzi scheme. Even as he built and invested in a slew of companies, the public still identified him as an actor or stand-up comic — not an entrepreneur.

Just last month, a clip of Jason Bateman went viral in which the actor questions why Hart appeared on ABC’s “Shark Tank.”

“Were you pitching something or judging?” Bateman asks during an episode of his podcast, “SmartLess.”

“What the f— is that?” Hart replies, laughing in disbelief. “I was a shark. I’m Kevin Hart, bitch! I’m not pitching an idea.”

Nick Cannon has as many business projects as he has children, and he wishes people would talk about that a bit more.

If Bateman were one of Hart’s 178 million Instagram followers, he might have a better understanding of the performer’s business acumen. On social media, Hart is constantly promoting his own companies: Gran Coramino (tequila), VitaHustle (nutrition supplements), Hart House (a plant-based fast food restaurant chain).

Last year, he started his own venture capital firm, which quickly took an outside investment from JPMorgan; Hartbeat Ventures’ portfolio now includes over two dozen companies, including Magic Spoon cereal and Therabody.

But his primary focus is Hartbeat, his media enterprise that in 2022 sold a minority stake to private equity firm Abry Partners for $100 million. The investment allowed Hart to expand his ranks to 80 employees and open offices in Hollywood, Atlanta and New York. The company has released 16 projects this year and has more than 70 in the pipeline planned for distribution deals with partners like Netflix, NBCUniversal and Audible.

The new company, Hartbeat, is a combination of two existing companies founded by Hart.

Many of those projects, including the Peacock celebrity interview show “Hart to Heart” or the forthcoming Netflix heist movie “Lift,” feature Hart; others showcase different stars, including Lil Dicky and Keke Palmer.

The connective tissue among all of these entities — his brand, in other words — is what Hart describes as “heart, home and love.” Which sounds a bit more PG than Hart’s comedy — or Hartbeat Weekend.

Owning and exaggerating his flaws is key to Hart’s stand-up. He jokes about his 5-foot-4 stature, his wandering eye, his tendency to snitch on his buddies. In film, his most successful roles have been opposite more formidable co-stars like Dwayne Johnson (“Jumanji,” “Central Intelligence”), Ice Cube (the “Ride Along” films) and Will Ferrell (“Get Hard”). He excels at playing an out-of-place underdog — loud, frenzied, irritated and almost always in over his head.

Hart is successful as a comedian and an actor, but it’s his portfolio that makes him peerless. Chris Rock, Ricky Gervais and Dave Chappelle command multimillion-dollar paychecks from streamers for their specials. Ellen DeGeneres and Jay Leno pivoted from comedy clubs to talk show stages. Adam Sandler, Amy Schumer and Jerry Seinfeld have their own production companies.

But none is — or perhaps even aspired to be — a mogul. And somehow, a man who openly parties so hard that he unabashedly wets the bed very much is.

Hart has always laid his ambition bare. When I first met him nearly a decade ago, he spoke about how he envied Jay Z’s success, hoping to follow the blueprint of “no longer just being a celebrity, but a person who controls an enterprise.”

“Eddie Murphy was a rock star, and if he had the tools we have, who knows how ridiculous he would be,” Hart told me in 2014, a year when he was starring in four movies. “With the tools I have today, what is my excuse not to try to get as huge as I can possibly get?”

When he arrives in Las Vegas for Hartbeat Weekend, it’s clear his lifestyle has leveled up significantly since then. At 1:30 on Thursday afternoon, the weekend’s first activation, the Gran Coramino Cup, is about to begin inside a cigar lounge at the hotel complex. Fifteen bartenders have been culled from a pool of 155 to compete for the chance to sling cocktails for a year at Hart’s various promotional tequila events.

Outside the lounge, at least a dozen people mill around, including a woman who creates content for Hart‘s TikTok channel, a trio of men with cameras who document his every move, his publicist, a tour manager and a tequila executive.

And when Hart sweeps in, he’s encircled by an entourage composed primarily of friends and family (as well as the three security guards who will flank him for the weekend). He’s on the phone, and everyone appears to be anxiously waiting for the call to end so they can get his attention. When it does, his publicist is one of the first to grab him, and she introduces us.

“Hey, how’s it going?” he says, his face obscured by a Prada bucket hat.

These are the only words we will exchange over the course of the weekend, even when we are in close proximity. He’s not rude, but he is preoccupied, bouncing around to chat with his crew. He definitely knows I’m here. He sees me with my notebook. He just doesn’t really seem to care. Which, frankly, makes things easier for me — we have an interview scheduled for after the weekend wraps; now, I can fully take in the scene.

And it’s a chaotic one. Hart may have few limits when it comes to talking about his bodily functions, but this all-access trip to Vegas comes with boundaries. Over the course of Hartbeat Weekend, he is constantly with the five friends with whom he did that podcast, commonly known as the Plastic Cup Boyz. That’s intentional — being surrounded by those he feels have his back makes him feel protected, but it also limits the amount of access others have to him.

“I think it comes from his upbringing,” says Wayne Brown, Hart’s tour manager and a member of that group. “He likes to feel that family love around him because that support system maybe wasn’t what it should have been when he was growing up.”

Hart has never shied from sharing his origin story, particularly in his comedy. As a kid in North Philadelphia, Hart was raised by his single mother, Nancy; his dad was a drug addict who was in and out of jail. His mom had Hart’s brother legally emancipated after he got mixed up in some criminal behavior as a teenager. She subsequently pinned all of her hopes on Hart, forcing him to fill his free time with a slew of extracurricular activities to ensure he stayed out of trouble. He has continually attributed his work ethic to his mom, who died of ovarian cancer in 2007.

So, yeah, it could be that Hart doesn’t flinch when eyes are on him because he’s used to such pressures. Or perhaps, given the events of the last few years, he has become somewhat immune to outside opinion — at times shielding himself in a cloak of defiance when his behavior is questioned.

On Dec. 4, 2018, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences announced that Hart would host the 91st Oscars ceremony. The decision was met with almost immediate backlash. Twitter users resurfaced homophobic jokes he had made earlier in his career — “Yo if my son comes home & try’s 2 play with my daughters doll house I’m going 2 break it over his head & say n my voice ‘stop that’s gay,’ ” read one 2011 bit — and demanded he apologize.

On Dec. 6, he posted an Instagram video revealing that the academy had also requested he apologize. He “passed” on making amends, he said, because he had already addressed the misguided jokes in years past. Hours later, however, he tweeted an apology and said he would step down from the hosting gig.

Kevin Hart is really and truly done with the Oscars.

The following year, he released a six-part Netflix docuseries, “Kevin Hart: Don’t F— This Up,” which followed him as he navigated the fallout. The show also delved into the aftermath of the 2017 cheating scandal that ensued when the comedian admitted he’d cheated on his second wife, Eniko Parrish, with a model in Las Vegas. The infidelity occurred while Parrish was eight months pregnant with the couple’s first child.

“When I got to see the effect that my reckless behavior had, that was, um — it was crushing,” he tells the camera in the series. “That tore me up. That’s probably the lowest moment of my life because I know what I was responsible for.”

Hart has a long and complicated relationship with Las Vegas. One of his best friends, longtime writing partner Harry Ratchford, told me that when Hart would argue with his first wife — they were married from 2003 to 2011 — the two men would retreat to Sin City as a refuge.

During one trip, they ran into Will Packer — then a fledgling producer who had yet to make hits like “Straight Outta Compton” or “Girls Trip.” Despite barely being familiar with Packer, Hart became convinced that the producer might be his entree into the film world.

“So he sent Will Packer a whole bottle to his table, and this is when he didn’t have that type of money,” Ratchford recalls. “It was like a $1,500 bottle or something. Kev just treated him like a king.” The move paid off, with Packer eventually giving Hart a role in 2012’s “Think Like a Man” and later teaming with him on the “Ride Along” films.

These days, Ratchford says, Hart will go to Vegas only if his wife is with him. “But even though he encountered a misfortune there, it’s always been somewhere where Kev can let his hair down, party, blow off steam and somewhat still move in obscurity.”

Indeed, though the Gran Coramino Cup is open to the public, the crowd of a few dozen onlookers is respectful, mostly concerned with documenting Hart’s appearance on their cellphones. After crowning a winning bartender, he toasts the room with a shot of tequila.

Six hours later, he is clinking another shot glass with friends. It’s 11:30 p.m. when he turns up at a lounge on the 66th floor of the hotel, where an invite-only gathering toasts his birthday. He and Eniko wear matching candy apple red ensembles. He’s escorted to a cordoned-off section of the room, which is kind of confounding since the 75 or so people in attendance are either his colleagues or homies. Comedian DC Young Fly and TikTok food influencer Keith Lee are among those granted VIP access.

A video montage of messages from loved ones, commissioned by Hart’s wife, starts playing on a flat screen. He stands at attention directly in front of the TV, smiling gleefully. There are tributes from the Plastic Cup Boyz, a motley assemblage of older men with whom he plays poker, and Ludacris, who tells Hart that it “takes a special person to be 100% themselves 100% of the time.”

After the video finishes, Stevie Wonder’s “Happy Birthday to Ya” starts to play and a cake is delivered to the VIP area. But Hart starts waving his hands, requesting that the music be lowered so he can address the room on a microphone. He is emotional, and he is drunk.

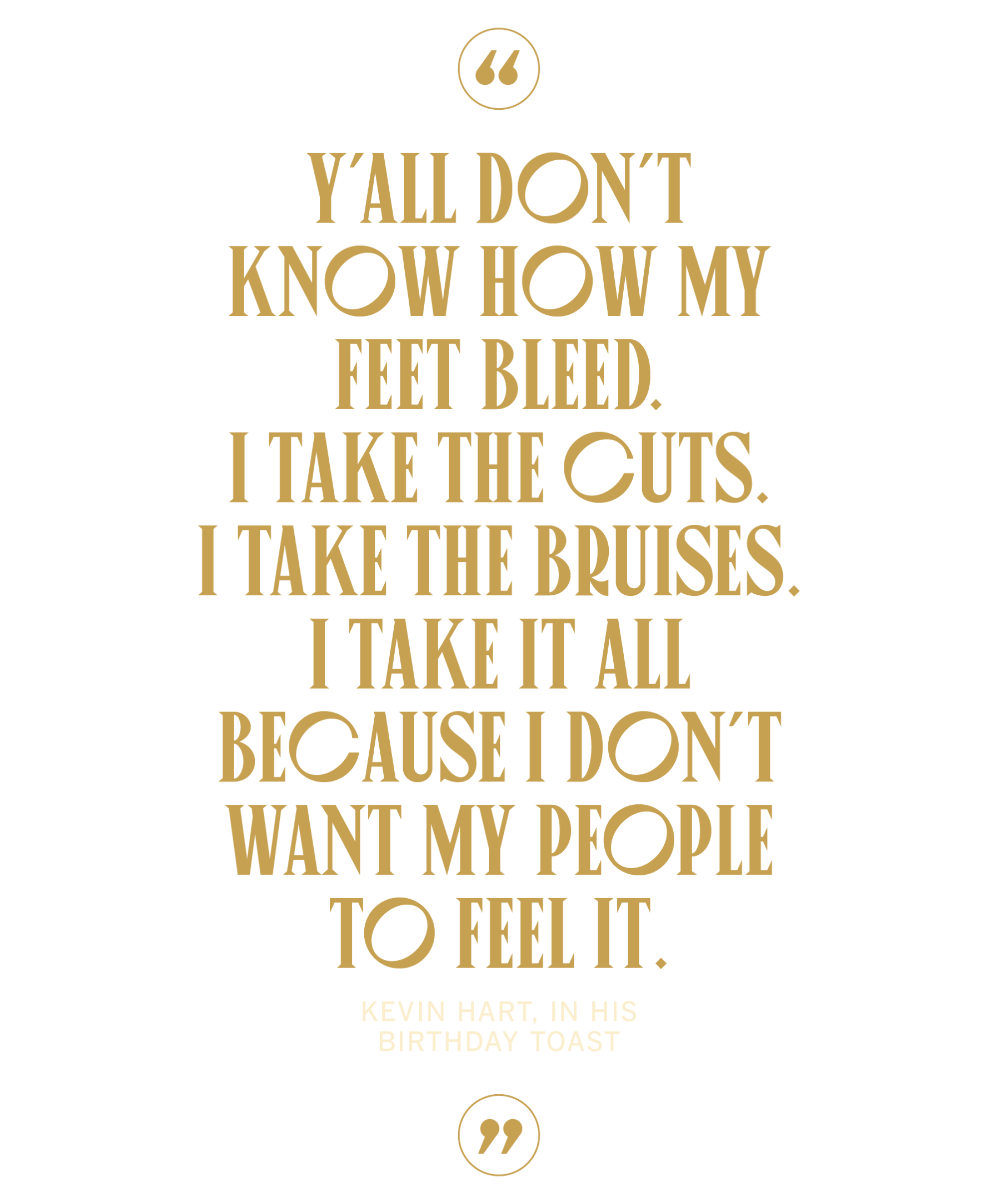

“In that video, I saw a lot of people I give a f— about,” he says, starting to tear up. “And to see that, that makes me feel like you give a f— back. That, to me — that’s the best gift.

“So I’ll say that in a respectful manner as a man that stands on f— glass,” he continues. “Y’all don’t know how my feet bleed. I take the cuts. I take the bruises. I take it all because I don’t want my people to feel it. That’s the s— that makes a man feel that it’s worth it.”

Everyone applauds and returns to the party. But Hart’s remarks stick with me. I take a sliver of cake —possibly the only person in attendance to do so — and stare at the newly erected Las Vegas Sphere illuminated against the sky. I wonder what has caused Hart to feel unappreciated by those closest to him. What is making this man’s feet bleed.

I don’t have much time to mull, however; the party is moving from the lounge to Zouk Nightclub for Ludacris’ performance. I have not been looking forward to this. While I enjoy “Move Bitch” as much as the next millennial, I am not genetically coded for nightclubs. Especially post-pandemic. So many bodies. Sweaty bodies. Yelling. Inebriated. Blinded by strobe lights. Deafened by bass.

But Kevin Hart loves this environment — he will go to Zouk on three consecutive nights this weekend — and so, dead sober, wearing a blazer and clutching a plaid notebook, I follow. The scene is reminiscent of the kind of thing you used to see on “Keeping Up With the Kardashians,” when Kim would go to a place like Tao to do a paid appearance. There are sparklers and shots delivered to Hart’s VIP area by attractive women. He is having a great time. When Ludacris finally goes on stage — an hour after he is scheduled to, but who’s looking at the clock? — Hart joins him, hyping up the audience.

This is the last thing he will remember that night, before waking up in soaked sheets.

“It didn’t go dark for me until after Luda and we started going with back-to-back shots,” he tells his friends during the live podcast taping the next day.

It’s 2:30 p.m., and his voice is hoarse. He was supposed to play poker this morning, but he canceled so he could sleep in. He’s wearing a pair of Crocs designed to look like the “Cars” character Lightning McQueen.

“Uh, let’s talk about how you was crying last night,” one of the Plastic Cup Boyz suggests.

“I got emotional,” Hart admits.

“He cried,” Na’im Lynn, a comic, informs the crowd. “And he said, ‘Y’all don’t know that I walk on glass.’ I don’t know what the f— that means.”

“I’m a provider,” Hart says. “As a guy that provides, I’m always the one giving gifts or giving a good time. So it’s the moments when people do things and they show you a level of appreciation and love that matter to me the most. So these jackasses actually did something nice for me.”

Hart’s boys take offense to this. They start listing the gifts they’ve given Hart: a truck that he later returned, a pair of diamond cuff links, a Peloton bike. They banter lightheartedly and take more tequila shots. Then it’s off to a dayclub for a pool party. It is 101 degrees outside. How in the hell is this man going to perform a sold-out stand-up show for 5,000 people tonight?

Science be damned, at 8:30 p.m., Hart emerges from his hotel suite with his wife, brother and two eldest children — Heaven, 18, and Hendrix, 15 — to walk to the theater. In the elevator, Heaven play-fights with her father, pretending to spar with him.

“What, you wanna run it?” she asks her dad.

“You don’t even sound right,” Hart responds, laughing at her vernacular. “Look at you. Nothing about you says, ‘I can defend myself.’ ”

Eniko stares down at her heels, seemingly regretting her shoe choice.

“How much more walking do we have to do?” she asks, trudging down yet another soulless hallway. “I hate this place.”

Finally they arrive at the theater’s greenroom, where three dozen people are already hanging out, picking from buffet trays. Tonight is the second-to-last show of Hart’s “Reality Check” tour, which began in 2022 and had 199 dates. Upstairs, in the wings of the stage, a handful of seats have been set up around a monitor for Hart’s friends to watch the show. Hart chills until the last possible minute before nonchalantly entering the theater when cued.

Despite the amount of añejo no doubt coursing through his veins, he gives a performance virtually identical to the version of “Reality Check” that began streaming on Peacock the same weekend Hartbeat is going on. (The special, his eighth, was filmed in the same Vegas theater in late 2022.) One of his best-received bits centers on how out of place he felt when he began protesting in the wake of George Floyd’s death. He describes how he turned up in “a salmon-colored V-neck and some khakis” when everyone else was in all black, toting a sign that read, “Black People Rock”; he was such an outlier, he says, that one of the leaders told him to just go home when the rubber bullets started flying.

Sixty minutes later, he bounds off the stage excitedly chanting, “One more show!” In a few hours, he will return to Zouk to see J. Cole. I will not be seeing J. Cole. In fact, I decide to leave Las Vegas the following day. Yes, there is still one day of Hartbeat Weekend remaining, when he’ll do his final stand-up gig and then watch Jack Harlow rap.

Brown, Hart’s tour manager, told me that his boss is always able to keep going because he’s an expert at sleeping on-the-go — if he has 10 minutes of downtime on a quick car ride, he’ll pass right out.

I do not possess this superpower.

Also, it’s clear that this is not the best environment to have a substantive conversation with Hart. His publicist and I agree to schedule the interview for when he returns to L.A. in the next few days, before expiration of the SAG-AFTRA negotiation extension.

But by Monday, it’s still unclear when Hart will be back in LA. He could be staying in Vegas to play poker. Actually, now he’s going to Palm Springs. It’s Tuesday. He isn’t answering his publicist. He’s with his boys. He’s distracted. He’s not looking at his phone. Finally, Wednesday morning, a suggestion: A 5 p.m. interview on Zoom, mere hours before an actors’ strike could start at midnight — after which an interview would be off the table.

He’s shirtless when he pops up on-screen, wearing nothing but two diamond chains. He’s videoconferencing from his iPhone and he seems distracted, accepting a plate of food, letting someone in from outside.

“I’m still recovering,” he says two days after leaving Vegas. “I’m not 26 anymore; 44 is on me now. So I can’t do that consistently — not with my schedule.”

I tell Hart that I’m still thinking about his now-infamous “walk on glass” speech. I ask him to describe some of the burdens he’s carrying.

“There’s things where I just bear all of the consequences,” he says. “I bear the burden of insurance risks or higher budgets. To take a team and travel with them is expensive. Sometimes that cuts into your bottom line.”

He tries not to talk about these things, he says, because he wants the people around him to feel comfortable. But money stresses him out. Always has. Ratchford says he used to tease Hart about the cash he kept on hand.

“I’m like, ‘Kev, are you sick?’” Ratchford says he asked. “You can’t just be sitting on liquid like that. He’d say he had it in case s— hit the fan. We call him Panic Paul because he’s always thinking worst-case scenario in every situation.”

Hart won’t say how close he is to being a billionaire, a title he’s long aspired to, or what the end goal is for Hartbeat. He’s already sold a minority stake in the company, but would he ever want to offload the entire business à la Reese Witherspoon, whose Hello Sunshine was acquired by a private equity-backed media company for over $900 million?

“Right now, it’s about owning something that can be on the side of the building that people will resonate with and understand,” Hart says. “I’m trying to create generational wealth and opportunity for my family and my family’s family. And also an ecosystem that provides job security for so many. As you do that, and as that brand grows, the decision gets harder to make as to what you want to do.”

Jeff Clanagan, Hartbeat’s president and chief distribution officer, says he’s considered Hart “more of a business executive than a comedian” for a few years now. “His time is really spent running and overseeing his business entities and investments, but everybody doesn’t really know that,” the executive says.

Hart insists he’s fine with that — fine with Jason Bateman’s befuddlement over his “Shark Tank” appearance. Because eventually they’ll see it. How hard he was working. How much he achieved. How he set his kids up for success.

Emily Ratajkowski opens up about estranged husband Sebastian Bear-McClard, Hollywood’s dark side, growing her Bitch Era Media empire and kissing Harry Styles.

All things in due time. That’s why he thinks he was able to ultimately move past the Oscars controversy: People saw his true colors after some time passed.

“Good people are good people. You can’t fake being a good person,” he says. “One thing that I have on my résumé that is probably the best thing is: ‘Kevin Hart lights up the room.’ This is from movie sets to the office.”

In the wake of the controversy, some criticized Hart for not working with queer collaborators. I ask if he’s made a conscious effort since 2019 to seek out LGBTQ+ partners.

At first, he’s defensive. He says he doesn’t know how his colleagues identify and wouldn’t ask about their personal lives.

At Hartbeat, he says, he’s actively trying to provide opportunities to those from underrepresented communities. The company has partnered, for instance, with the Sundance Institute on a comedic screenwriting fellowship for Black women.

His goals are lofty — “How do you put more jobs in households? How do you create revenue streams for other families? What change are you making in the inner city, the place that you’re from?” — and I wonder if he will ever be satisfied, with an ambition that seems limitless.

“If there’s a sky, and you know that sky is high, you don’t know the true ending to it,” he says. “But if you can keep going, there’s an opportunity to touch the highest part of the sky. Some people may want to touch it. Some people are ambitious enough that they just may want to do it.

“I have to be an example of the change that we hope to see in the future. And I think I’m doing an amazing job of it,” he continues. “I don’t have to boast or scream it from the mountaintop. You see it. It’s clear. It’s visible. And those that don’t, it just means they’re not looking.”

Take that, Bateman.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.