Splash Mountain closing day: Why Disneyland’s long goodbye is long overdue

- Share via

- Share via

In the summer of 2020, amid the cultural reassessment and nationwide protests following the killing of George Floyd, fans of Disneyland’s Splash Mountain were put on notice.

The 1989 ride, popular for its five-story drop but made infamous by the controversial movie that inspired it, would close. Disney said at the time it wanted a more inclusive concept, one free of association with the racist 1946 film “Song of the South” and its white-centered depiction of slavery and stereotypes.

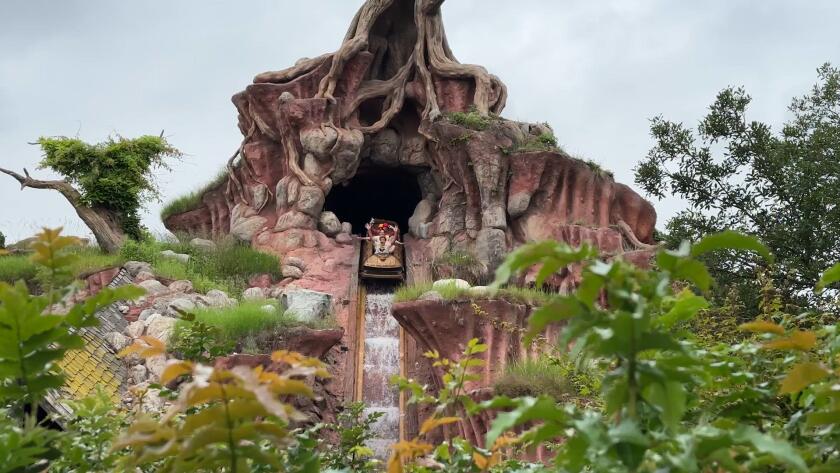

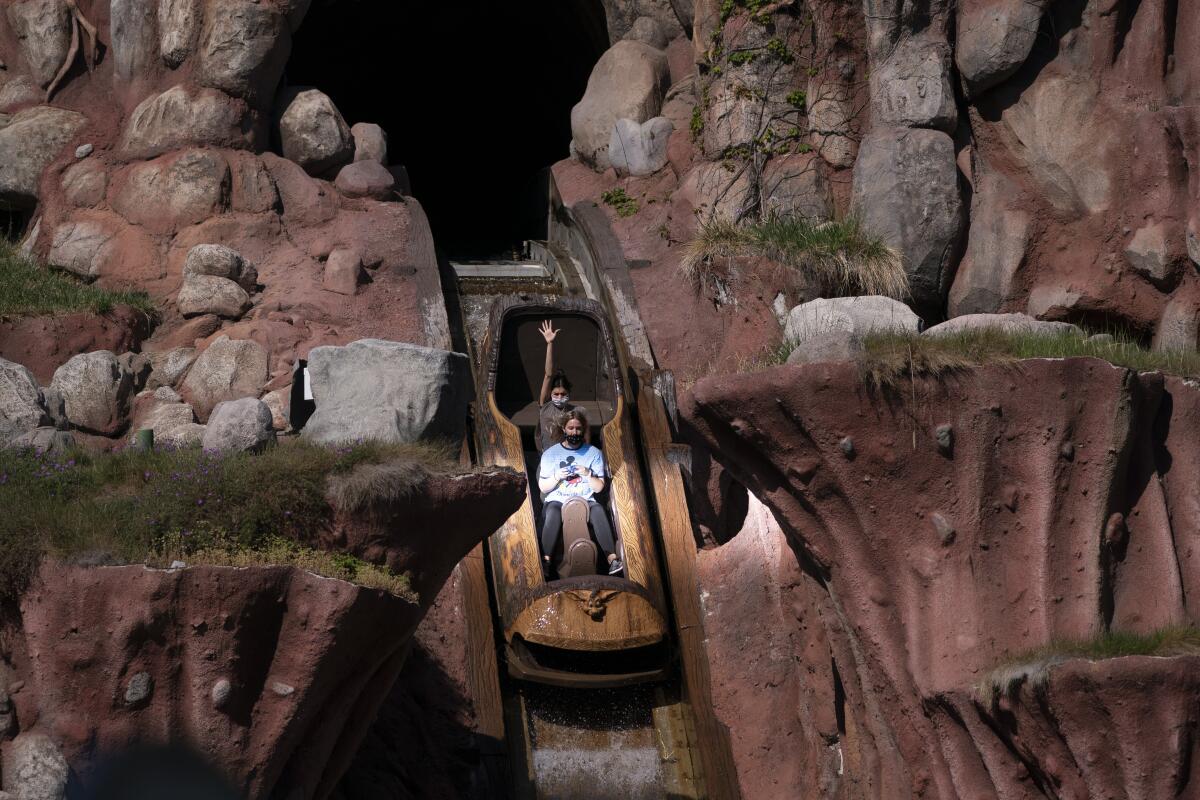

On Tuesday, Disneyland fans gathered in Critter Country to mark the closure of Splash Mountain, which will not reopen with the park on Wednesday. Some cheered as log-shaped cars dropped from the top of the Disney-constructed mountain known as Chickapin Hill, while others, wearing fan-made T-shirts commemorating the day, clutched plushies of the Splash Mountain characters for the ride’s mid-fall photo. Most were hopeful for what’s to come, an attraction themed to “The Princess and the Frog,” the 2009 fairy tale that stars the company’s first Black princess. Some, however, were sorrowful that a piece of their childhood would be lost.

“I didn’t get to go to Disneyland until I was in my teens, and this was one of the first rides I ever rode,” said Stefanie Re, 39, who lives near Portland, Ore. Re had come to the Disneyland Resort with custom-made Mickey Mouse ears that referenced the ride and film’s song “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah.” “It’s just a big memory for me. It’s something I wanted to achieve as a kid — watching the commercials and getting the picture. It’s nostalgia. A happy memory.”

Re was optimistic that “The Princess and the Frog” makeover, known as Tiana’s Bayou Adventure and scheduled to open here and at Walt Disney World in 2024, would be “something better.” While not everyone shared Re’s opinion — some wished the ride wasn’t changing — Splash Mountain’s three-year goodbye can’t help but feel overdue.

Splash Mountain was doomed from the start.

Times articles from the late 1980s cited Disney spokespeople already trying to justify the attraction, noting that it would skirt controversy by focusing solely on animated scenes and would avoid any references to the Reconstruction-era South. But even at the time of the ride’s opening, “Song of the South” was in the Disney vault, kept out of movie theaters and, eventually, off of streaming platforms. Hindsight criticism is always easy, but Splash Mountain will go down in history as a significant miscalculation from Walt Disney Imagineering, the arm of the company devoted to theme park experiences.

By 2003, Disney representatives were declining to commit on future releases for “Song of the South.” In 2020 Chief Executive Bob Iger called the movie “not appropriate in today’s world.”

Splash Mountain also signaled a tentative approach to theme park design, one in which creatives no longer created original projects — Pirates of the Caribbean, Haunted Mansion, It’s a Small World, Big Thunder Mountain — but rather were beholden to film and television intellectual property.

Park guests said Tuesday that the ride stands apart from the movie. But Splash Mountain is still a ride in which arguably the most popular song, “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah,” has connections to minstrel shows. The two cannot be completely divorced, and the words “Song of the South” are emblazoned on the large, critter-adorned ferry boat in the ride’s finale. Splash Mountain was born of another cultural era, its themes chosen in part due to its location in Disneyland — which in the late ’80s was known as Bear Country — and as a way to reuse audio-animatronics from the patriotic America Sings.

The end of that era felt relatively subdued Tuesday. Waits around lunch time hit three hours, but for most of the morning the 65-minute posted queue was more like 25 minutes. Disney in the past has attempted to turn ride closures into something of a party, complete with celebratory merchandise, but there were no Splash Mountain trinkets, save for a commemorative coin from a penny-press machine. Although trolls accused Disney of being “woke,” the scene Tuesday was quiet except for fan sites setting up livestreaming stations.

Work is underway in nearby New Orleans Square to welcome Tiana’s Bayou Adventure. New Orleans Square’s French Market Cafe is being remade into Tiana’s Palace. The quick-service dining location, boasting New Orleans staples, will open later this year.

Concept art for Tiana’s Bayou Adventure shows a more mystical attraction, one that Disney promises will celebrate New Orleans with a tinge of fantasy, courtesy, likely, of Mama Odie, the 200-year-old bayou fairy godmother from the film. The ride will feature a robust number of audio-animatronics — Disney has said “dozens,” many likely repurposed from “Splash Mountain” — to culminate in a giant Mardi Gras musical celebration.

“I wish it didn’t have to close. I hope what comes next will be fun and enjoyable,” said Arielle Lohmeyer, 32, from Salt Lake City. Lohmeyer has loved the attraction since age 6. “I don’t think there’s anything that could replace it that will ever mean as much to me as Splash Mountain.”

Famed Disney Imagineer Tony Baxter, known for spearheading Big Thunder Mountain and helping to bring the works of George Lucas into Disney parks, has argued that Disney in the early to mid-’80s often was forced to look to the company’s deep past for inspiration, as films of the era struggled to resonate with audiences. Splash Mountain follows Br’er Rabbit and his attempts to live a life of bliss while eluding Br’er Fox and Br’er Bear.

“When Splash Mountain came to life over 30 years ago, the wave of Disney Animation that started with ‘The Little Mermaid’ had not yet begun,” Baxter said in a 2020 news release. “New stories would give us characters, music and wonderful places that now reside in the hearts of audiences everywhere.”

In terms of how Splash Mountain ranks amid the Disney classics, as a pure ride experience I’ve always found its genius to be in its track layout more than its story, message or heart. There appears to be a light moral center, as Br’er Rabbit, often not at home, is chasing a life of hedonism. His steadfast devotion to a “laughing place” nearly gets him killed, but it’s a toss into the briar patch — the attraction’s five-story drop, said to reach about 40 to 45 mph — that saves him in the last moment. A rousing finale among friends and family recenters his priorities.

At least that’s always been my take. Others may have different interpretations, as the cartoon vignettes are designed to generate laughs more than they are to tell a story. That’s all well and good, and Splash Mountain has plenty of details — possums, bees, turtles, owls and more, many of them caught in mischief — to distract. Once inside the mountain, there’s action on nearly all sides of us, including above. Animals sing, play instruments and avoid the rain by sitting under psychedelic mushrooms. Splash Mountain has a dedication to old-fashioned Disney craft, one that puts an emphasis on feeding us dioramas rather than a plot.

Yet even so the narrative feels especially loose, in part because tonally the ride shifts suddenly from jovial, free-spirited partying to doom, in the form of vultures who want to put an end to it for no clear reason. But after the thrilling drop, we’re back amid a large jamboree. Life is one big guffaw, after all.

Along the way the sudden sharp turns obscure many of the ride’s lighter drops. Splash Mountain works because it always feels a work of surprise. We never quite can see when the log will lurch forward into a moderate drop.

Michael Yip, 26, of San Francisco, said the ride to him has always been about “overcoming my fears” and staying positive. Plus, Yip said, “I love the musical sequences.”

None of that will go away when Splash Mountain reemerges as Tiana’s Bayou Adventure next year. The biggest change is Disney will at long last be rid of this cringe-inducing chapter of its past.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.