Commentary: Richard Gilman, the complicated subject of a new memoir, helped raise the bar for theater criticism

- Share via

Whether it’s possible to separate the artist from the art is a question that has grown more heated in recent years, as the atrocious behavior of men — powerful white men, in particular — is no longer being condoned as readily as it had been for millennia.

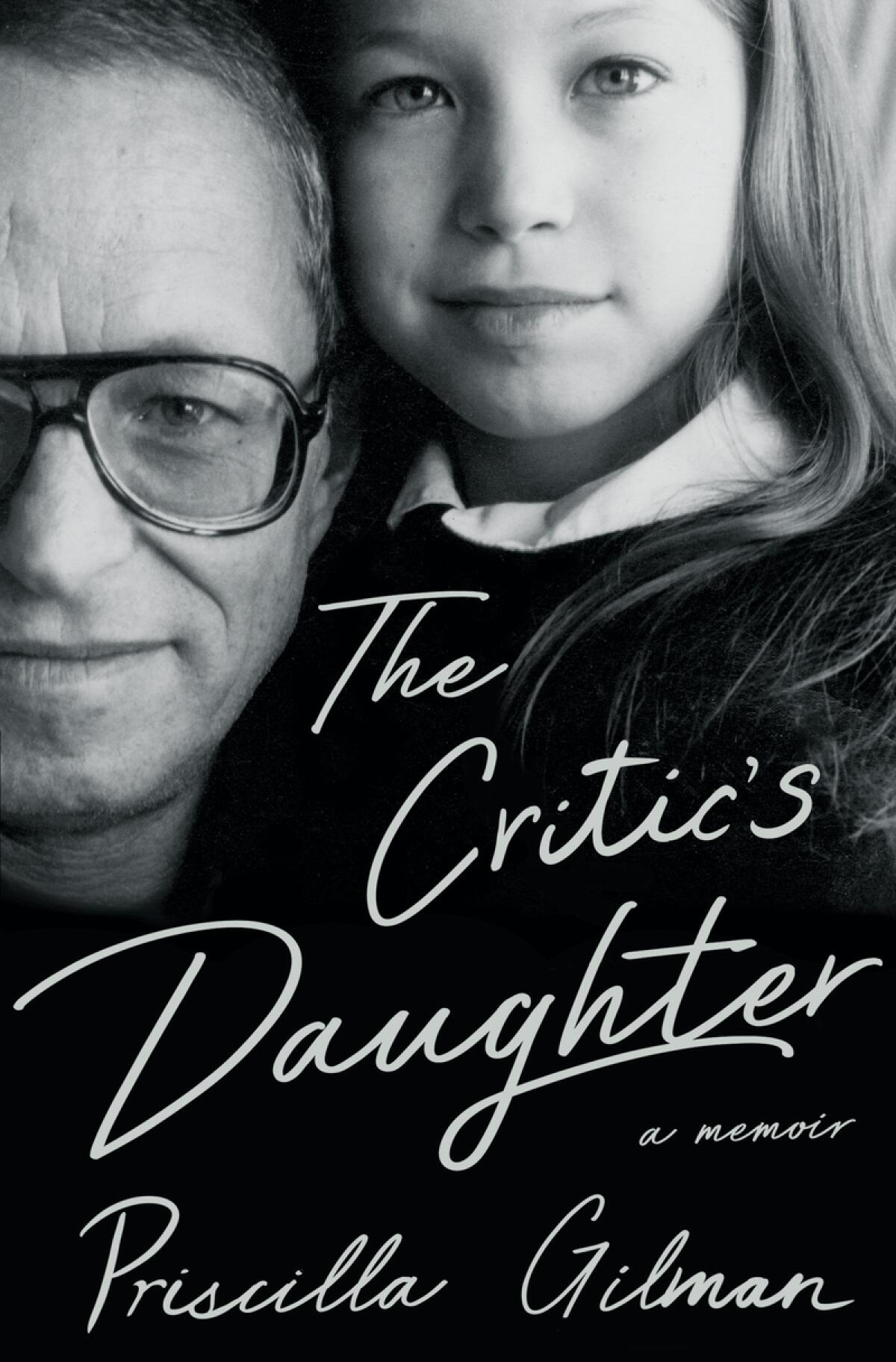

In her new book “The Critic’s Daughter,” a memoir about her father, literary and theater critic Richard Gilman, Priscilla Gilman extends the discussion by considering whether it’s possible to separate the critic from the criticism.

She attempts to honor the intellectual legacy of her father, who died in 2006, while painting a portrait of him that is both loving and gimlet-eyed about his virtues and deficiencies. The book is her story about a brilliant yet profoundly flawed parent, and her motive in telling it seems to be in part self-therapy.

Ms. Gilman takes pains to capture his complexity in a memoir that’s neither condemnatory nor exculpatory. She includes excerpts from his brilliant writing, though without much context for their inclusion. But the bigger problem is that she doesn’t rigorously interrogate her own worldview. The framework through which she views her father — a framework embedded with assumptions about money, class and prestige — is insufficiently examined.

Her sins are the sins of loving too much and in too self-abnegating a fashion. The Cordelia to her father’s Lear, she is inevitably the sad, noble heroine of every anecdote she tells. But the cramped filial perspective treats the life of a critic as though it were a figure in a child’s dollhouse.

“To live is to battle with trolls in heart and mind; to write is to sit in judgment of oneself.” These words from playwright Henrik Ibsen were often quoted by her father in the classroom — and they diagnose precisely where her memoir falls short.

I felt squeamish reading about Gilman’s ugly divorce from Lynn Nesbit, Ms. Gilman’s hard-driving literary agent mother. His daughter’s anxious account of his fetish for dominatrix fantasies (a subject he doesn’t shy away from in “Faith, Sex, Mystery,” his memoir about his conversion to Catholicism and subsequent departure from the church) left me feeling as though I were invading the privacy of a relative or former therapist.

I’m not related to Gilman and I’ve never pretended to be a patient on his couch. I was, however, his student for five years in the 1990s. (My name is included in the book’s acknowledgments with other former students and colleagues.) Gilman served as my advisor during my graduate studies at the Yale School of Drama, where he was co-chair of the dramaturgy and dramatic criticism department. But more than that, he provided the intellectual foundation for my education in the theater.

His voice still resounds within me, urging me to hold fast to the artistic values he painstakingly articulated and promulgated to generations of students, who have come to share his conviction, as he writes in the foreword to his seminal book “The Making of Modern Drama,” that “great plays can be as revelatory of human existence as novels or poems.” A champion of drama as “a source of consciousness,” Gilman challenged the entrenched anti-intellectualism of the American theater.

In a culture of fractured attention spans, devalued expertise and bullying group-think, it is salutary to recall the example of a critic whose allegiance wasn’t to the commercial or ideological marketplace but to the art form he served. A dance critic was recently befouled with dog poop by a German ballet director unhinged by a bad review. Gilman understood “the necessity for destructive criticism,” the title of one of his indelible essays, the way a gardener understands the necessity for weeding. His work wasn’t a branch of publicity even as it sought to elevate the truly excellent from the meretricious.

A hard-bitten New York intellectual of the old stripe, Gilman spoke with a smoker’s rasp, enjoyed a drink and comported himself like a rakish pirate in a denim jacket. He was not the only Yale faculty member known to have had affairs with his grad students, but his behavior had cleaned up by the time I arrived at the school.

There’s no defense for the slovenly ethics of the past. The Yale School of Drama, now the David Geffen School of Drama, is a different institution today, more egalitarian, less homogeneous and a good deal more conscientious about maintaining order and safety.

Students are more empowered and faculty members are no longer held up as demigods. This is all for the best, but I am nonetheless grateful for having been exposed to Gilman’s unadulterated critical sensibility.

His pedagogy offered something that wasn’t widely available elsewhere. He taught students how to think. His criticism workshops, a curricula staple for budding critics and dramaturgs, were an experience in literary vivisection, as he homed in on every cliché and woolly idea in that week’s student essay.

Fuzzy writing, he contended, was the result of fuzzy thinking. Hyperbole offended him. Praise had to be earned in language that was proportionate. If you feel as strongly as you claim, you ought to paint an honest picture and not resort to the breathless language of blurbs.

Gilman had made a name for himself as a critic at Commonweal and served as drama critic for Newsweek and then the Nation. His demanding prose style was forged in an era when small-circulation quarterlies still had some cachet. But the days of Partisan Review were dwindling, and though he recommended me to an editor at the Village Voice, where I found a publishing home, he wasn’t preparing us for contemporary job fairs.

There were limits to his scope. He was anti-theory at a time when graduate students in the arts and humanities could not afford to be oblivious of Foucault, Derrida and the army of faddish post-modernists. (My incorporation of queer theory into my dissertation put me on thin ice.) Jargon was the enemy, but graduate students dreaming of tenure would have to search elsewhere at the university not to be shut out of the discourse, a word he no doubt would have found lazy.

His name may no longer be widely recognized, but his legacy shouldn’t be underestimated. Gilman, along with Robert Brustein and Eric Bentley, created space in American culture for serious dramatic criticism, aimed not at academic specialists or anxious cultural consumers but educated readers hungry for a deeper aesthetic engagement with the theater.

In elucidating the way Ibsen, Strindberg and Chekhov established the foundation of modern drama, he opened minds to the revolutionary accomplishments of Pirandello, Brecht and Beckett. His philosophical orientation made him especially receptive to the avant-garde, but he admired professionalism, discipline and skill above all and had little patience for the self-deluding rhetoric and empty political gestures of theatrical cults.

As “Faith, Sex, Mystery” movingly attests, Gilman was a seeker. Theater was part of his spiritual journey, but not in any woo-woo way. The relationship between the material and spiritual realms paralleled for him the relationship between form and content in great works of art.

One of Gilman’s truisms is that a play like “Hamlet” isn’t paraphrase-able. You can’t reduce a masterpiece to a message. Form isn’t a container for content. They work in tandem to communicate what only the drama in its full substance can convey. The larger lesson to be drawn is that simple binaries, in art as in life, falsify reality.

The theatrical subject that interested Gilman most was being — consciousness, the awareness of the self, the experience of time and the inescapable plight of radical uncertainty. As an art form in which human beings are incarnated, drama is a natural conduit for metaphysics and ontology. Gilman recognized that what Sophocles was pursuing in “Oedipus Rex” and Shakespeare in “King Lear,” Chekhov was similarly exploring in “The Three Sisters” and Beckett in “Waiting For Godot.”

For Gilman, the life of an artist was always subordinate to the work. He was disdainful of the mania for biography. Criticism, in his view, brings us deeper into the mind of a playwright than an account of bad marriages and professional setbacks and triumphs. In his magnum opus, “Chekhov‘s Plays: An Opening Into Eternity,” he locates the Russian playwright’s spiritual vision in the details and decision of his art.

He doesn’t ignore the man but he prioritizes the part of him that endures — that is worthy of enduring. To read Chekhov via Gilman is to come into communion not only with Chekhov’s soul but with Gilman’s own.

“The Critic’s Daughter” puts Gilman in the spotlight, but for reasons he likely would have found objectionable had the author been anyone other than his beloved daughter. Great writers transcend their personal squalor. “We shed our sicknesses in our books,” declares D.H. Lawrence. Gilman quotes these words in his Village Voice tribute to Jean Genet — and they apply equally well to his superlative criticism.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.