Column: ‘Twilight’ once showed L.A. how to heal. Now it’s showing us we’re still broken

- Share via

“My dad is a historical figure, you know?”

An almost reverent hush had fallen over the audience at the Mark Taper Forum.

Lora Dene King, the daughter of Rodney King, wanted to say a few words before a performance of “Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992,” the seminal documentary-style play about the chaotic uprising that followed the acquittal of four police officers in her father’s beating.

Indeed, 30 years after its premiere at the Taper and stint on Broadway, “Twilight” returned to Los Angeles this month. But this time, instead of playwright Anna Deavere Smith embodying dozens of real-life characters — using quotes from hundreds of interviews with activists, cops, jurors, academics and business owners after the acquittal — there’s a cast of five. And it has been updated, with new reflections and new scenes.

It’s the first performance of “Twilight” the younger King has ever seen.

Anna Deavere Smith and director Gregg T. Daniel revisit the writer/performer’s groundbreaking solo documentary theater piece, retrofitted for a cast of five, in a new production at the Mark Taper Forum.

“He deserves this,” she said of the way the play memorializes her father, drawing somber nods from the audience. “We watched him suffer.”

We still do.

It was only in January that attorneys for the family of Tyre Nichols compared his brutal beating by Memphis police to what the Los Angeles Police Department did to King in March of 1991. And even when King’s name isn’t mentioned, the specter of him is present in videos of George Floyd, Keenan Anderson, Tamir Rice and so, so many other Black men and women who didn’t survive encounters with police.

So it’s impossible to watch a performance of “Twilight” in 2023 and not use it as a measuring stick of how far we have and have not come in both our actions and our attitudes.

Are we still, as the character Twilight Bey says so poignantly at the end of the play, “stuck in limbo,” like the “sun is stuck between night and day”?

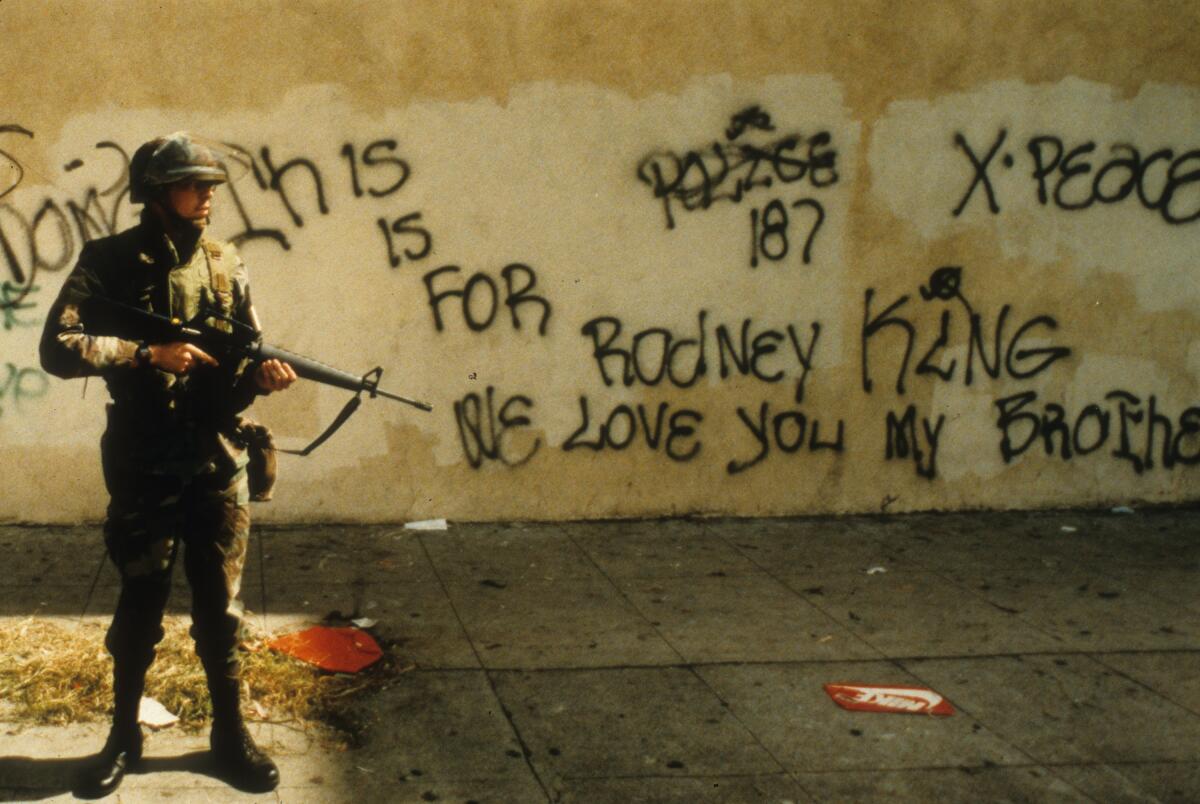

Thirty years is a long time. Long enough for a new generation to be born and grow up not knowing and long enough for an older generation to forget all the ways that Los Angeles was still smoldering in 1993. Scars from the destruction and violence were still fresh then. Entire blocks had been laid to waste. The anger and distrust were still there, too, along with uneasy questions about what might come next. .

Angelenos, like many Americans, were searching for healing and understanding, and for ways to build multiracial and multi-ethnic coalitions. “Twilight” was hailed for giving audiences all of that by providing a window into the thinking and the suffering of people, using their own words.

We heard from Korean liquor store owners about fearing gangs, not understanding the racial dynamics of Los Angeles, and being thought of as “model minority” immigrants while also being marginalized.

We heard from Latino Angelenos who were just as wary of police as Black Angelenos, but were torn between solidarity and aspirations toward whiteness and away from the bottom rung of the socioeconomic ladder.

We heard from Black Angelenos about the rampant racism in L.A., and the culture of fear and pattern of brutalization by police.

And, of course, we heard from police officers about the racist, us versus them mentality with which they patrolled the streets.

In 1993, long before social media and smartphones, much less racial reckonings, such reflections were revelatory. “Twilight” opened people’s eyes to the powder-keg-like conditions that turned the acquittal over King’s beating into an explosive uprising that cost 63 lives and more than $1 billion in property damage.

More important, the play also suggested a path forward for Los Angeles.

With five Black ex-cops charged with murder in Memphis, Tenn., Lora King reflects on what has changed since her father was beaten by the LAPD in 1991.

As the character Bey, who in real-life helped hammer out the truce between the Bloods and Crips in Watts in 1992, says: “I see the light as knowledge and the wisdom of the world, and understanding others. In order for me to be a, to be a true human being, I can’t forever dwell in darkness. I can’t forever dwell in the idea of just identifying with people like me and understanding me and mine.”

Those words are just as powerful in 2023 and they were in 1993.

Indeed, the updated “Twilight” still provides that much-needed window of understanding and opportunity for healing in Los Angeles. I just worry that, all these years later, audiences are too exhausted, too jaded or maybe too overwhelmed to look through it to see the people on the other side.

This certainly seemed to be the case when I saw “Twilight” last week. It was Black Out Night at the Taper, designed for Black people “to be centered and welcomed into a historically white-dominated spaces.” And so most, but not everyone, in the audience was Black.

Except for a few murmurs of sympathy for a Korean American character who was shot, and for the character of Reginald Denny, the white man who was dragged from his truck and beaten to a pulp, it was clear which side the most people were on. No additional understanding needed.

Then again, we also aren’t the strangers to each other that we were in 1993.

We’ve all seen the rise in anti-Asian hate and many have stood — or at least tweeted and grammed — in solidarity. We’ve also seen the mass shootings, first in Monterey Park and then in Half Moon Bay, that have exposed the fallacies of the “model minority” stereotype and highlighted the need for more community-based mental health services.

In the now infamous audio recording of four Latino leaders, including three L.A. City Council members, plotting to consolidate political power, we all heard the anti-Black racism and the colorism. And with the leaked snippets going viral, the condemnation was swift, particularly by younger activists of all races and ethnicities.

And month after month, we all see videos of Black people dying in violent encounters with police, usually during a traffic stop. We all know what will happen next, from the press conferences and the marches, to the criminal charges and internal investigations that will go nowhere, to the last-resort lawsuits that cost taxpayers millions of dollars.

In 2023, we are anti-white supremacy, anti-police violence, anti-systemic racism, pro-community, pro-solidarity, pro-equity. But for some reason, we’re still here in the present with Rodney King, the historical figure.

Thirty years is a long time to be stuck in limbo. To live in twilight.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.