- Share via

After multiple New York runs, “Slave Play” is making its West Coast debut at the Mark Taper Forum, where it is, for the first time, presented on a thrust stage — that is, one that is surrounded by seats on three sides, as if it were “thrust” into the audience. In comparison to any of its stagings elsewhere, this Los Angeles production of Jeremy O. Harris’ provocative piece is arguably a more immediate and exposed experience for both the viewers and the cast.

“It has a different relationship to the audience, that’s for sure,” says director Robert O’Hara. “It feels much more intimate in a way that’s dangerous and scary, but also, because of the nature of the thrust [stage], it requires another level of attention be paid to the actors and also the play itself. There’s no protection here.”

Presenting “Slave Play” at the Taper is somewhat of a full-circle moment (beyond the signature shape of the Welton Becket-designed building). The earliest performance of the layered satire — in which three interracial couples try to remedy their sexual connections through role-playing and group therapy — was put on in a Yale School of Drama basement, with viewers surrounding three sides of a stage sectioned off by tape on the floor.

“As the play happened, I got to watch people watch each other,” Harris recalled in a preshow speech last week. “That for me, became the play. It became a play about audiences being in conversation with other audiences.”

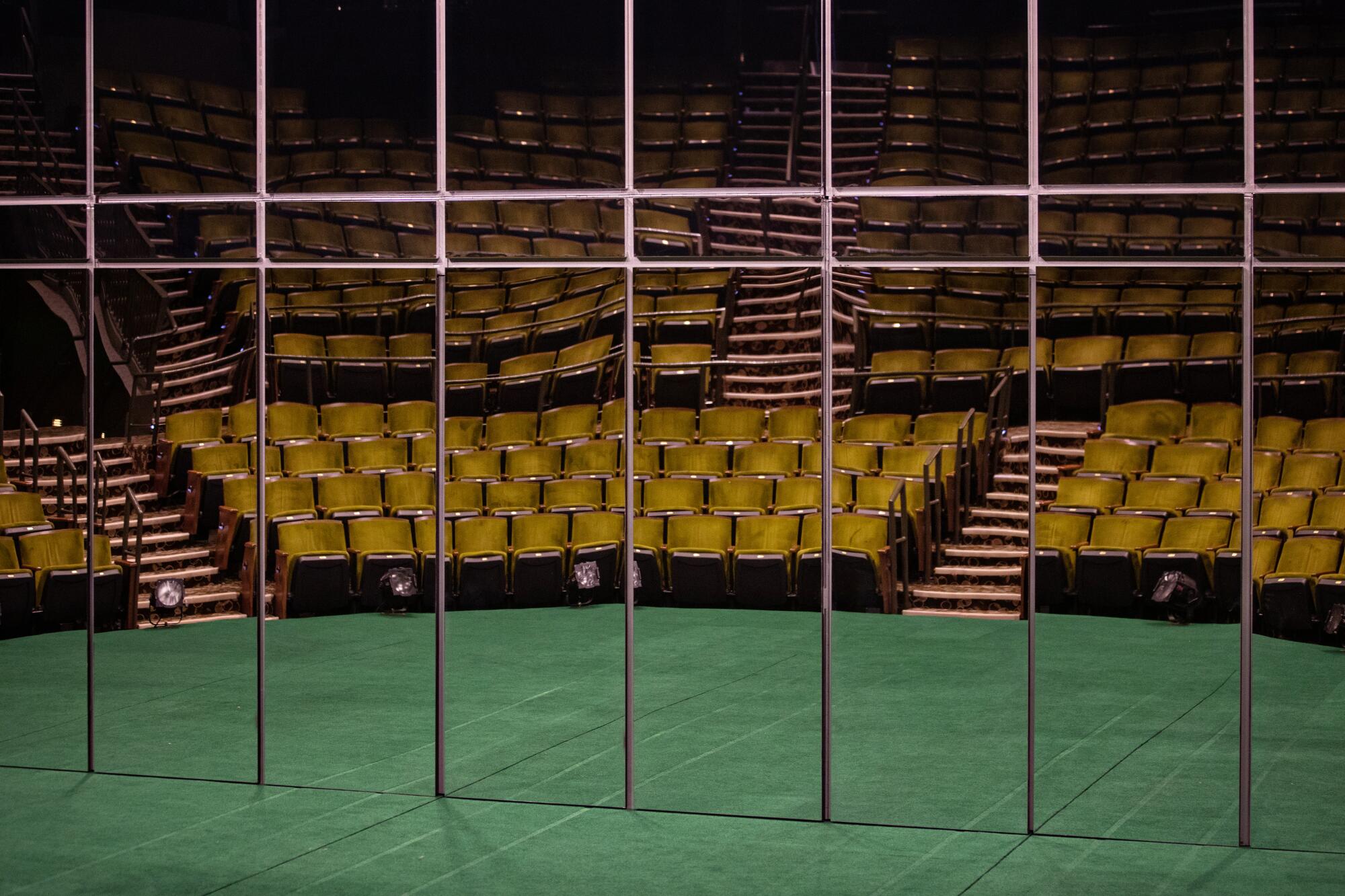

Set designer Clint Ramos replicated that setting for multiple off- and on-Broadway venues — all of which had proscenium stages, with their generally uniform seat orientation and a larger separation between the stage and the audience — with a floor-to-ceiling wall of mirrors upstage. While Ramos was initially inspired by “the theatricality of how couples perform intimacy with each other with mirrors placed above them in their bedrooms,” the effect forces the viewing of the performance and seeing the reflection of its audience to become inseparable. “We are watching ourselves watch the play,” he says. “The mirrors force me to deal with the fact that I am actually not exempt from what’s happening onstage.”

That maneuver is exponentially amplified at the Taper, where more than 700 stadium-style seats surround the thrust stage like a semicircle. Add in those giant glass mirrors and house lights that never go all the way down, and the Taper becomes a wall-to-wall arena in which every attendee, whether seated in the first row or the last, becomes part of the show, performing their reactions for the rest of the audience. And if someone gets up and walks out, everyone in this entire theater sees it.

“It’s like, you can’t escape it, you can’t avoid engaging with the play while it’s happening,” says Antoinette Crowe-Legacy, who reprises her Broadway role in the L.A. run. The same goes for the actors: “It’s been jarring to be in a slightly smaller space. You can hear the reactions, you can feel that energy right next to you: the conflicting ideas about what’s happening, people actively trying to decide if it’s funny — and if they should laugh.”

To accommodate the Taper’s configuration, the cast redid the blocking of numerous sections — decisions that, surprisingly, accentuate the text. For example, the action of the second segment now spills over well into the crossover area, with dueling therapists traversing the aisles and retreating to their respective corners like boxers in a ring.

And when a character seizes focus during communal conversation, the amount of measurable space they’re choosing to take up in that moment is an unignorable visual. “Unless you were really in the nosebleeds on Broadway, you wouldn’t see that carpet at all,” says Ramos. “Now, all of the floor work that the actors are doing is so magnified.”

Without the proscenium-specific need to play to just one direction or project to the balcony of a Broadway house, the actors “can be more natural and movements can be more fluid,” says O’Hara. That’s especially helpful during the third act, in which the mirrors pivot toward each other and Crowe-Legacy recites what is essentially an extended monologue. “It’s actually easier,” Crowe-Legacy says, “because, since the space is a little bit smaller, I can feel like I’m whispering and know that people will still hear me and they’ll still be drawn into what’s happening on the stage. And that is, in some ways, a little bit gentler.”

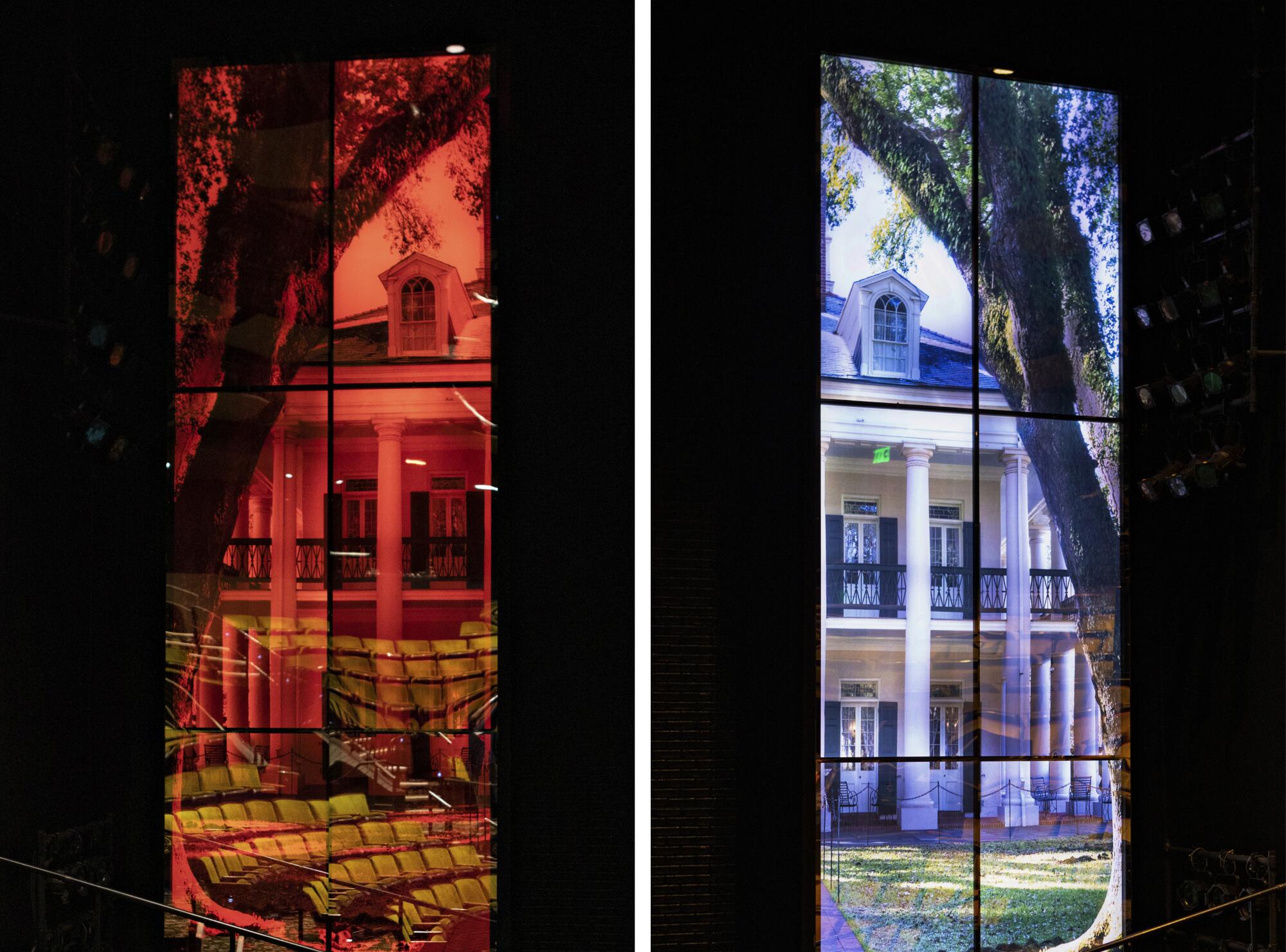

The onstage mirrors are initially bookended by images of an antebellum plantation presented through two-way mirrors that, along with the oversize acrylic lyrics to the Rihanna song “Work,” act as a kind of juxtapositional frame for the first act and those watching it. To keep up the intended effect, “We have to keep everything as clean as possible, because any scratches and fingerprints are super visible,” says Center Theatre Group production manager Krystin Matsumoto. “Our team tried a whole array of cleaners and cloths to figure out the best ones for this. It’s constant maintenance.”

“Slave Play,” which plays at the Taper through March 13, reopens the theater after two years of shutdowns due to the pandemic. For those who experienced the piece in its earlier incarnations at a proscenium, this thrust staging may seem more powerful and immediate than previous stagings; for others, it might be more offensive or difficult to swallow. Regardless of those views, those watching will undoubtedly be seen.

“Celebrate the people who are watching with glee, be revolted by the ones who are watching with too much glee,” Harris told the audience in his speech. “For the first time in its professional production history, you all will be able to look across the stage and see how other people are inhabiting the space and engaging with these ideas — or not. I’m so excited about that.”

Jeremy O. Harris, author of “Slave Play,” has taken Broadway by storm this season and hopes to leave it irrevocably changed.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.