- Share via

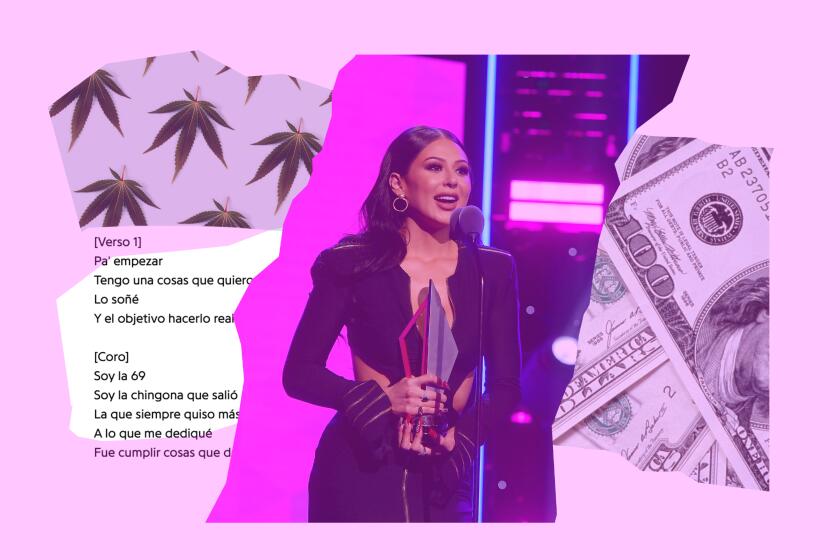

When the beauty influencer known as Jenny69 debuted her first single on YouTube at the end of September, it immediately went viral — though probably not for the reasons she’d hoped. “La 69” features a catchy enough tune: some evocative Spanish guitar licks set against a backdrop of head-bobbing corrido tumbado. In the video, the singer wears eye-catching outfits that reveal what God and a good plastic surgeon gave her. But the flat delivery — Jenny69, to put it kindly, cannot sing — inspired an internet pile-on.

At one point in the tune, Jenny, who was born Jennifer Ruiz in Riverside, shouts out the Inland Empire. Viewers on YouTube responded by offering condolences to Riverside in the comments. The criticisms in no way dissuaded Ruiz from releasing a very sexy club mix of the tune late last week.

Her future as a singer may be limited, but Ruiz has nonetheless made a strong statement — with her style.

In the video, which, as of this writing, has more than 9 million views, she appears in a sleek white suit and equally sleek white cowboy hat. Her heels are impossibly high and her bejeweled fingernails impossibly long. Her makeup is flawless. And, above her bounteous cleavage, she displays a sparkling pendant bearing the outline of an AK-47. In a graphic that accompanies the single’s release, Ruiz cradles a resplendent rooster.

Jennifer Ruiz, better known as Jenny 69, went viral with her 14-second clip on Instagram teasing her debut corrido. ‘La 69’ became a meme. It also became a hit.

Jenny69, “la chingona que salió de Riverside” — the badass who came out of Riverside, in English — as one of her lyrics goes, has become a highly visible ambassador of the look known as “buchona.”

Hyperconsumption, hyperpower

“Buchona” is a slang term first popularized in the Mexican state of Sinaloa as a way of describing the flamboyant girlfriends of a generation of 21st century narcos who are referred to in the masculine as “buchón” or “buchones.”

Sinaloa, of course, is the coastal Pacific region that is home to the Sinaloa cartel, once led by the infamous Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman (now serving a life sentence in the U.S.). Guzman’s wife, former beauty queen Emma Coronel Aispuro, is the buchona whose name comes most easily to everyone’s lips — the buchona máxima, if you will. She recently pleaded guilty to federal conspiracy charges in U.S. federal court and is awaiting sentencing, but her looks and her lifestyle are still a subject of passionate discourse on the internet.

If in its early days “buchona” referred to a narco’s girlfriend, over the years, the term has taken on added meanings, expanding to include women who are linked to or have active roles in the cartels. It can also include women who simply adopt the buchona style — women with a taste for flashy clothes who don’t hide their love of partying, money or men.

Buchona Cosmetics, a brand launched by South Texas beauty influencer Siomara Tellez, recently featured an image on its Instagram account with the phrase “Buchi-Boss.” The definition describes “an empowered woman who kicks ass.”

Narco culture has long had a way of seeping into the mainstream, not without attendant concerns about the glorification of violent traffickers. Buchona culture remains, for the time being, largely an object of fascination — often because it is focused not on cartel administration but physical style.

And, as with anything narco, that style’s defining trait is excess: The boobs are big, the booty is round, the waists are waif-thin and the lips pillowy. Hair is worn straight and waist-length, and nails (also long) often feature baroque levels of decor. The makeup, likewise, is heavy duty, centered on dramatic eyes trimmed with fake lashes. Clothes are worn sausage-casing levels of tight, and you’re not a buchona unless you’re showing off luxury brands, preferably Versace or Louis Vuitton.

Elements of rural, northern Mexican life — such as cowboy hats — are also integrated into the look, albeit in highly glamorized ways.

It’s all about “hyperconsumption,” says Alejandra León Olvera, a Mexican theorist who studies narco culture and is completing a post-doctorate in the subject at the University of Murcia in Spain. “They are not conscientious consumers. They are not about being green or being responsible. It’s about consuming what represents power.”

And through that power, she adds, “they position themselves as hyperpowerful.”

Journalist Ana María Solozábal is investigating the jailhouse activities of a notorious trafficker inside a Bogotá prison when she learns from an inmate that her father, a judge who was assassinated by the cartels when she was a young girl, may have been linked to those same cartels in unsavory ways.

Not faking the funk

Buchona style is an aesthetic Ruiz embraces well beyond the frame of her song “La 69.” On her Instagram account, @jen_ny69, which has 2 million followers, Ruiz promotes her namesake line of buchona fashion, featuring body-hugging ensembles, some of which have a Versace-meets-Hermès scarf kind of vibe. The clothing line’s Instagram account, @jennysixnine (122,000 followers) features Ruiz in one of her looks accessorized with a cowboy hat. The caption reads: “Buchona s— isn’t for everyone.”

Last month, after her single debuted, Ruiz materialized for an interview with internet personality Pepe Garza in her décolletage-revealing white suit and white cowboy hat. “Yo no estoy faking the funk, así soy yo,” she said, in Spanglish, of her cultivated buchona look. “Me encanta la mota. Me encanta ser buchona vibes. Me encanta este estilo de vida.” (Translation: “I’m not faking the funk, that’s the way I am. I love weed. I love being buchona vibes. I love that lifestyle.”)

The audio from that interview has gone viral — relentlessly spoofed on TikTok.

How did a young woman who was born and raised in Riverside, who made her name as a beauty influencer — in 2017, she appeared in The Times, talking about pink lipstick — come to embrace a style connected with narcos?

Ruiz did not respond to several inquiries from The Times. But the answer is easy to find within popular culture. All you have to do is look.

OG buchonas

On TV, there are countless shows devoted to narcos, and one of the most famous — the smash 2011 telenovela “La Reina del Sur,” starring Kate del Castillo — features a woman at its heart. Her character, Teresa Mendoza, was one of television’s early buchonas: a tough, business-minded lady who dressed to the nines while looking for love and building a trafficking empire. Others have followed in its path, such as “Las Buchonas,” a 2018 collaboration between the Univision and Televisa networks that tells the story of four beautiful women with ties to the drug trade.

In music, the figure of the buchona is everywhere.

The late Jenni Rivera (who hailed from Los Angeles) would, at times, take on its stylistic trappings — at one point posing for photos in a white suit while holding a gun (a look that Jenny69 is likely paying tribute to with her own all-white ensemble). More contemporary is Sinaloa crooner Ely Quintero, who rocks glam ensembles while singing about women in the drug trade. In a recent duet with reggaeton star Rosa Pistola, the pair can be seen at the Culiacán chapel devoted to Jesus Malverde, an uncanonized Robin Hood figure who serves as the patron saint of narcos.

The buchona has even inspired entire odes. The bouncy 2010 jam “La Buchona,” by banda singer Chuy Lizarraga (who also hails from Sinaloa), is one of them: Ay viene la buchona vestida y a la moda / Sus uñas decoradas su boca bien pintada.

(In English: “Here comes the buchona, dressed up and in fashion / Her nails are decorated, her lips are nicely painted.”)

Lizarraga’s catchy song is regularly employed as a soundtrack on TikTok.

And that is just one sliver of the buchona pop culture juggernaut.

The lives of buchonas, their flamboyant styles and their taste for plastic surgery are regularly chronicled in Spanish-language media outlets. Vloggers do roundups devoted to top buchonas. And internationally, people have adopted the style, both ironically and not.

A popular theme on social media is “fiestas buchonas” or “buchifiestas,” parties in which partygoers wear shiny shirts and pose before elaborate black-and-gold backdrops, sometimes with guns. (Some obviously fake; others, hard to tell.) Social media was set ablaze last month by video of one such fiesta held for an 8-year-old girl.

Plug the word “buchona” into any e-commerce search engine and you’ll turn up vast collections of buchona fashion. And TikTok, YouTube and Instagram are stuffed with makeup tutorials that promise the buchona look.

Recently, I found myself absorbed by an 18-minute instructional video by the personable Mexican beauty influencer Yoshi Meza (more than 755,000 YouTube subscribers and 3 million Facebook followers) who manages her makeup brushes and the theme at hand with a dexterous touch. “It’s a subject you have to handle with tweezers,” she says as she launches her tutorial, “because it’s a little delicate.”

Mainstreaming narco culture

If once there was a desire in Latin America to create a distance between narco culture and the mainstream, that desire has all but evaporated.

“The narco has come out of the closet,” says Mexican photographer Mayra Martell, who has chronicled various aspects of the drug trade — including buchonas — as part of her work. “We have this idea of the narco as very marginal, when it’s not that. It’s a new social class.”

And it’s a phenomenon that isn’t confined to Mexico. In 2011 José Rodrigo Aréchiga Gamboa, a high-ranking assassin in the Sinaloa cartel known by the nickname “El Chino Antráx,” was photographed at a Las Vegas boxing match in cozy embrace with Paris Hilton.

Like a lot of slang, the exact origins of the term “buchón” are uncertain.

Some have connected it to the word “buche,” Spanish for a bird’s crop — a space in the animal’s throat where it can store food, giving the animal a puffed-up appearance. Others link the word to the popularity of Buchanan’s whiskey among the narco classes in Sinaloa. (In “La 69,” Ruiz can be seen holding a bottle of Buchanan’s 18 Year Special Reserve.)

Whatever its origins, the buchón and buchona aesthetic comes as part of a confluence of social factors in the mid-2000s, says León Olvera, who studied buchonas as part of her doctorate at El Colegio de la Frontera Norte in Tijuana.

There is the rise of the Movimiento Alterado, a musical movement (with connections to Los Angeles) that does little to obscure its links to the drug trade and whose song lyrics often dwell on hyperviolence. Fashion and musical tastes are likewise shaped by an increased exchange between Mexican and Colombian cartels, and reggaeton and hip-hop join norteño and banda as favored musical styles in areas like Sinaloa. Along with the music comes fashion, including bedazzled baseball caps and Ed Hardy shirts — which are added to a style palette that had long centered on tight jeans and cowboy boots.

Those rural elements are important. If previous generations of narcos had aspired to upper-class respectability, the buchón aesthetic rejects that.

“It’s not the fresas [preppies] of Mexico City in their polo shirts,” says Carolyn Castaño, a Colombian American painter from Los Angeles who has long investigated narco culture in her work. “They are embracing a rural culture — a rural culture with money.”

It was a Barbie-themed birthday party most kids could only dream about, with carnival rides, hundreds of pink balloons and a theater-worthy set featuring gold chandeliers and a rosé-colored throne.

The moment marks a shift in gender roles for women.

The archetype of the passive mafia wife — who claims not to know how her man makes his money — gives way to a woman who is more self-possessed and embraces the world she is from. Buchonas may still be playing second fiddle to the men, but they talk tough, shoot guns, flaunt their sexuality and boast about their capacity to party. It’s an ideal that regularly turns up in lyrics by singers like Rivera, Quintero and Melissa Plancarte, known as “La Barby Grupera” (and the daughter of an actual trafficker).

Traditionally, within Latin American culture, for a woman to admit she drank too much would be to invite negative scrutiny, says León Olvera. Among buchonas, it’s a badge of honor. “It’s saying, of the men, ‘I am taking their space.’”

Naturally, the internet and social media have fueled the phenomenon.

“It’s not about looking like the old narco wives,” says Castaño, who produced a prescient series of works inspired by the wives and girlfriends of cartel leaders in the late 2000s. “It’s about looking like Kim Kardashian and being an influencer.”

The sultry Claudia Ochoa Felix, who was linked to an assassination squad within the Sinaloa cartel, and was frequently likened to Kim Kardashian for her voluptuous style, had a wildly popular Instagram account in which she documented her looks and her jet-setting ways. (In the wake of her death, the result of an overdose in 2019, Instagram tribute accounts flourished.)

Coronel Aispuro is treated on social media — as well as the regular media — as a fashion icon. And, in fact, an account on Instagram bears her name, @therealemmacoronel, along with a coveted blue check mark. (Instagram did not respond to a request for comment about whether the account is real and how exactly one verifies the social media of a cartel leader’s wife.)

Buchonas are so plentiful on social media that when Martell began her photo project in Sinaloa, she was able to track them down by following the places they tagged on Instagram. “They would say, ‘I’m at X spa,’ and I would go to that spa and order a treatment,” says Martell. “Or they would say they were at a restaurant, so I’d go to that restaurant. And that’s how I began to meet them.” In this manner, she was even able to meet and photograph Ochoa Felix.

Monument removals and a replica of the Templo Mayor pyramid infuriated critics, but can Mexico’s populist government spark an Indigenous cultural renaissance?

“What’s incredible is that the women in Sinaloa are getting rich,” says Martell. “They have these entire markets in girdles and beauty products.”

Their role as fashion and beauty icons gives them a level of public influence that is often denied the men.

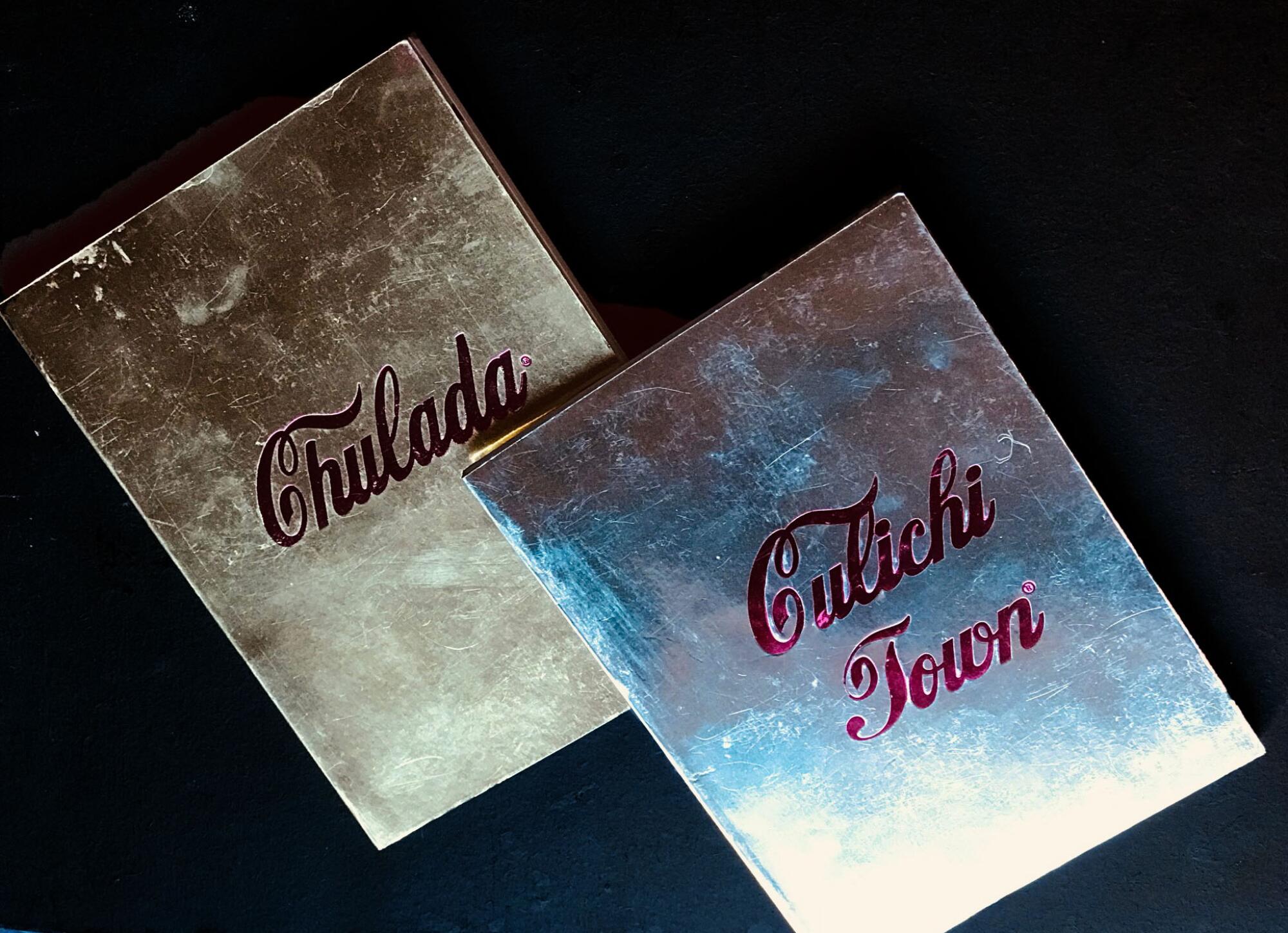

Martell has chronicled narco-culture for years, beginning with the violence that has racked her native city of Juarez for decades. She is compiling some of her work into a series of six artist books — among them, “Chuladas,” “Culichitown” and “Gore” — which she hopes to publish next year.

Buchonas, in particular, represent an intoxicating blend of glamour and authority.

“You have these powerful women,” she says. “It’s not this Mexican woman who is submissive, without money. She uses Chanel, Gucci, Swarovski. It’s a search for an identity of power.”

Which explains why a beauty influencer like Jenny69 would be tempted to make the buchona brand her own.

In her interview with Pepe Garza, Ruiz had all the signifiers down pat: the exaggerated hourglass curves, the revealing clothes, the glam makeup. She talked about loving Buchanan’s whiskey and having a gun made. She dropped a reference to “buchona s—.”

At one point, Garza asks her if she has been to Mexico. Ruiz says that her parents used to take her all the time as a girl but that has since changed. “Now they won’t let me go because it makes them fearful.”

If in the popular culture, the buchona aesthetic seems on the verge of becoming kitsch, in the real world, its milieu comes with consequences that can mean life or death.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.