Furloughed workers, Arthur Miller’s ‘Death of a Salesman’ is talking to you

- Share via

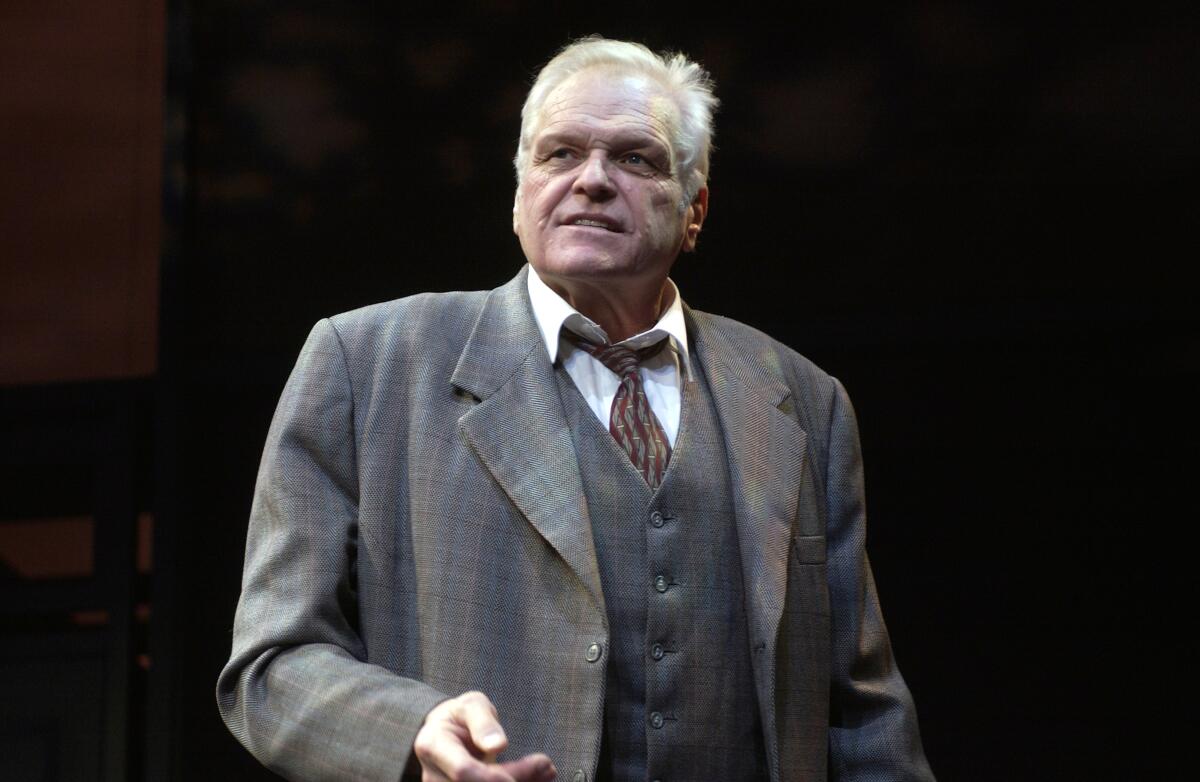

Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman” had been on my mind even before the death of Brian Dennehy, who won a Tony for his portrayal of Willy Loman in the 1999 Broadway revival. How could it not be? As the pandemic lays waste to the economy, the play reminds us of the unchanging truth of an American dream dangled for the many but obtainable only by a ruthless few.

Dennehy, a prodigious actor drawn to prodigious roles, delivered a battering ram of a performance. His Willy, a salesman aggressively trapped in a delusive way of thinking, would rather die a martyr than admit to being sold a bill of goods about success.

The bravado of the salesman, in Dennehy’s barreling rendition, couldn’t conceal the shame of a husband and father who fell agonizingly short of his own grandiose expectations. The power of the performance, as with much of the actor’s impressive body of work, didn’t derive from great variety. Dennehy pounded the same note with different degrees of intensity. But the limited range helped drive home the limited options of his character, whose eagerness to win prevents him from seeing that he’s been playing the wrong game.

As time catches up with Willy, the old salesman loses his job, his self-respect and, eventually, his life. Recognizing the tragic trajectory while it’s still unfolding, Linda exhorts her cynical son Biff — once the object of Willy’s pride, now a reflection of his failure — to stop tearing down his father before it’s too late.

“Willy Loman never made a lot of money,” she pleads, as much in anger as in sorrow. “His name was never in the paper. He’s not the finest character that ever lived. But he’s a human being, and a terrible thing is happening to him. So attention must be paid. He’s not to be allowed to fall into his grave like an old dog. Attention, attention must finally be paid!”

As workers everywhere are being sacrificed by employers who have extremely low thresholds for economic pain, the hobbled figure of Willy Loman looms large. Protagonists in great dramas aren’t passive victims. They contribute to their downfalls through missteps, blunders and excesses that reflect on their characters. But their plays ultimately tell a larger story.

Willy’s case is no different. Miller, bending time to give us the subjective experience of a tragic life, depicts a character, a “common man,” to use his own formula, who has internalized all the wrong lessons of American capitalism. Willy has bought into the punishing myth of rugged individualism he continues to proselytize to his sons even as he has become the walking embodiment of its empty promise.

Now in his 60s, he is spent, unable to make the regular trek to New England to peddle his wares yet too exhausted to acknowledge the error of his salesman’s faith. Wandering between past and present, he is plagued by regret and doubt. The shabbiness of the crowded Brooklyn neighborhood, in which nothing has a chance to grow anymore, is a constant reminder of how his dreams have come to naught. Still, his own diminished opportunities haven’t shaken his conviction that his sons can “lick the world” if only they clean up their acts and seize their chance.

Miller’s great gift as a dramatist was for steadily applying pressure until a dramatic movement exploded in a climax of moral and emotional significance. One such scene that resonates with our pandemic moment is when Willy goes hat in hand to his employer.

After 34 years of service to the firm, Willy asks Howard whether he can get off the road and find a position in the local showroom. He’s worn out. He’ll take 65, 55, 40 dollars a week.

“Business is business,” Howard tells him, letting him down with a litany of clichés. Willy cannot accept this lack of loyalty. Howard’s father, Willy’s former boss, had assured him that he would be taken care of. “Kid, I can’t take blood from a stone,” Howard replies, his endearments only rubbing in his granite refusal.

Willy erupts in words that should resonate with workers everywhere abandoned by their employers in an hour of need: “You can’t eat the orange and throw the peel away — a man is not a piece of fruit.”

Whenever I hear the line, I hear the voice of Dustin Hoffman, who was my first Willy Loman. Hoffman’s salesman, a little guy accustomed to talking a big game, shambled into his boss’ office with right on his side. But quickly he’s made aware of his smallness by the indifference coming across the other side of the desk. Willy’s fury is like the crazed buzz of a bug looking for a window as a newspaper readies for a whack.

America, reeling from the economic devastation of the coronavirus crisis, is in the grip of a “Death of a Salesman” moment. Miller’s play speaks directly to the plight of the 100,000 employees whose pay was recently stopped at Walt Disney Co. This is only one of many such mass furloughs, but the example seems especially illustrative of a broken system. The decision, according to The Times, “leaves Disney staff reliant on state benefits — public support that could run to hundreds of millions of dollars over coming months — even as the company protects executive-bonus schemes and a $1.5-billion dividend payment due in July.”

Miller was quick to point out in an introductory essay that “Death of a Salesman” isn’t an anti-capitalist screed. He acknowledged the cold “common sense of businessmen,” which understands that when “a man gets old you fire him, you have to, he can’t do the work.” He wasn’t arguing with what he accepted as “social facts.” He also reminded his readers that the “most decent man in ‘Death of a Salesman’ (Charley)” is a capitalist. What’s more, Bernard, Charley’s son, “works hard, attends to his studies, and obtains a worthwhile objective” while coming from “the same class, the same background, the same neighborhood” as the Loman family.

As a playwright, Miller wasn’t writing propaganda or settling ideological scores. He was searching for truth in memories and images that led him to create order and meaning out of the chaos of experience. But he possesses that quality that the great Shakespeare critic Alvin B. Kernan, writing on American plays in 1967, diagnosed as lacking in our drama — historical imagination.

Willy’s private story, the tale of a father unable to deal with the guilt and shame of failing in the eyes of those he loves most, is set against the socioeconomic backdrop of a nation that values the ambition of the individual above the security of the collective. For Miller, Willy’s fate is sealed by the way he has “committed himself so completely to the counterfeits of dignity and the false coinage embodied in his idea of success.” He is in part a casualty of the economic injustice he would consider it heretical to question.

Classics, even of the contemporary variety, are multifarious enough for us to reengage their dramatized truths, to wring new meanings in contexts that are at once new and uncannily familiar. Miller clearly isn’t advising owners, CEOs and boards of directors how to deal with their balance sheets in a pandemic. But the play does ask us to question the values we adopt in an economic system as brutally survivalist as the one Willy finds himself in.

“Death of a Salesman” also sheds unexpected light on circumstances that would have been unimaginable to the author. When asked what Willy is selling in those bags of his, a point left conspicuously vague, Miller had a ready answer: “Himself.” His remarks on the nature of his salesman, recorded in the notebook he kept during the play’s germination, may bring to mind another self-marketer dominating our crisis-ridden national stage:

“A salesman doesn’t build anything, he don’t put a bolt to a nut or a seed in the ground. A man who doesn’t build anything must be liked. He must be cheerful on bad days. Even calamities mustn’t break through. Cause one thing, he has got to be liked. He don’t tell you the law or give you medicine. So there’s no rock bottom to your life. All you know is that on good days or bad, you gotta come in cheerful. No calamity must be permitted to break through, Cause one thing, always, you’re a man who’s gotta be believed. You’re way out there riding on a smile and a shoeshine. And when they start not smilin’ back, the sky falls in. And then you get a couple of spots on your hat, and you’re finished. Cause there’s no rock bottom to your life.”

Willy Loman and Donald Trump are on the surface polar opposites. But it’s a sign of the enduring truthfulness of Miller’s vision that parallels are glimpsed where you might least expect to find them.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.