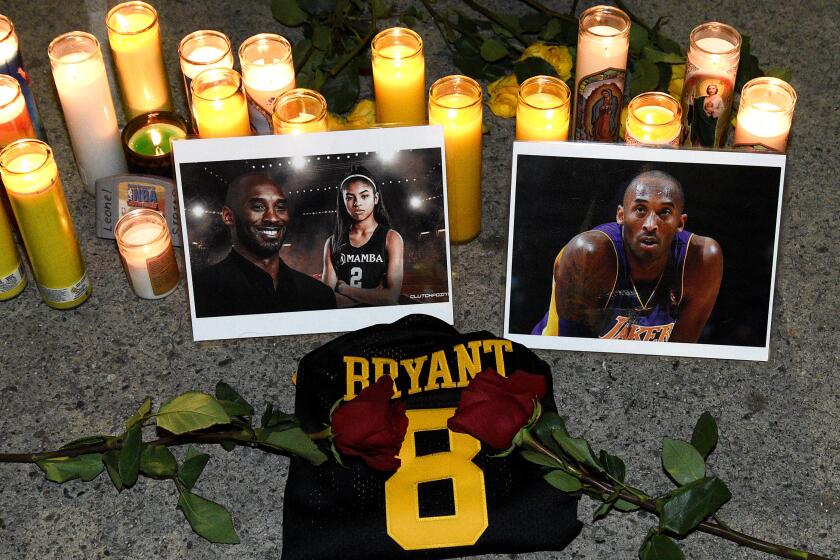

Column: For my 13-year-old basketball player, Gianna Bryant’s death was a bigger blow than Kobe’s

- Share via

My youngest daughter and I were at a friend’s baby shower when we learned of Kobe Bryant’s death. I was glancing at my phone when a breaking news alert flashed across my screen, and I gasped.

“What?” Darby said, reaching for her own phone. So she learned as I did that Kobe’s 13-year-old daughter, Gianna, had been with him when the helicopter crashed. I squeezed my own 13-year-old daughter’s hand under the table and said, “We’ll talk about it after,” and we returned, as best we could, to the shower’s excitement and joy.

We did talk about it later, on the drive home, but I was just as shocked and numb as she. “I feel so sad,” she said as we walked into the house. “That is how everyone is going to feel,” I said unhelpfully, mechanically. “It is just a terrible, terrible thing.”

She did her homework, I made dinner. My husband and I spoke with our 21-year-old son, who was choking up halfway across the country; “I didn’t even realize how much he meant to me until I heard the news,” he said. “It’s like he was just part of my life.”

“I’m still sad about Kobe,” my daughter said later. “But mostly I’m sad about Gianna.” And then she burst into tears. “She was only 13. I’m 13. She wanted to play for UConn and in the WNBA. She was really good. It isn’t fair.” She collapsed, sobbing, into my lap.

Complete coverage of the death of Kobe Bryant, his daughter, Gianna, and seven others in a helicopter crash.

Darby plays basketball too; she had seen Kobe coaching Gianna’s team a few times at tournaments. It was a bit weird being at a tournament where Kobe was coaching, like glimpsing a unicorn at a horse race. Everyone was always respectful, but still there were lots of surreptitious pictures taken, including by me.

Darby’s team never played the Mambas; the Mambas were always in a higher bracket. But we watched a game or two, and they were, not surprisingly, very good. Disciplined and unified. Watching Gianna play, I remember thinking you wouldn’t know she was the daughter of the coach or that the coach was a superstar; she was a talented part of a talented team. For any parent of a student athlete, the photos of Gianna in uniform, the highlights reels circulating on social media were heartbreakingly familiar.

Once, the Mambas were taking the court as Darby’s team was leaving it, and he stopped to tell them that they had played a great game. The girls vibrated with joy. I tweeted about it, and Kobe followed me on Twitter; for half a minute, my kids thought I was cool.

When I read the details of the crash, all I could think was: He was just a dad taking his kid to basketball. Something millions of parents do pretty much every weekend. Yes, it was a helicopter, but when it comes to accidents, it just as easily could have been a car. The means of transport doesn’t matter so much as the routine of it. It could have been any of us; frankly, it was far more likely that it would have been any of us.

Through her sobs, my daughter asked the questions we all ask: Why? How? What will tomorrow be like? She cried for his family; how would they cope? She cried for their final minutes; were they scared? She cried because she was afraid that, in all the grief over Kobe, people would forget Gianna.

Investigators are looking into why a helicopter carrying Kobe Bryant, his daughter and seven others slammed into a Calabasas hillside.

I didn’t tell her then what I feared — that some of Gianna’s teammates and their parents might have also been killed in the crash.

She cried because really there was nothing to do but cry. There was no criminal to excoriate, no policy issue to denounce, no paparazzi to blame. You cannot turn fury on the fog. It was, at least in early reckoning, an accident. A terrible, awful, random accident.

That somehow made it worse. I let her cry for a while, and then I tried to answer some of her questions. Their deaths, though horrifying, would have been very quick. If Gianna had been scared, her father was there to comfort her. Their family would feel terrible pain, but they would be surrounded by friends and relatives, and they would feel the love and support of their city and country.

As for “why,” well there is no answer, is there? Sometimes wonderful things happen, like the beautiful shower we had just been part of, and sometimes terrible things happen. With any luck, the grief so many feel about Kobe, Gianna and the other seven lives lost will help unite us, will remind us that we are all just people to whom wonderful and terrible things happen, and so maybe we should be a little nicer to each other.

My daughter and I are lucky; we have lost people we love but never so young, never so tragically. But Darby has come of age in the era of school shootings, and she knows young lives can be cut short. This felt different, she said. She felt she knew Kobe and Gianna. Not because of the Lakers but because of the Mambas. Because she had seen them doing something she herself was doing. She knew they were special, but still they were recognizable to her as coach and player, father and daughter. We talked about how Darby could think of them like that when she played basketball, how she could offer up gratitude for being gifted the time Gianna had not.

Nine people, including Kobe Bryant, were killed when a helicopter crashed and burst into flames in Calabasas.

We talked about some of the people they might hang out with in heaven, because we believe in it, and about the fear that even a belief in heaven does not prevent. I couldn’t tell her that nothing like that would happen to her or me or the people we loved, because I don’t know that. Being famous doesn’t protect anyone from tragedy but neither does not being famous. No one wants their child to cry, but sometimes the only thing you can do is cry with them. No one wants their child to be afraid, but sometimes you have to acknowledge the fear in order to manage it.

We prayed for Gianna and Kobe and all the people who loved them, lighted a candle in front of a small statue of the Blessed Mother for them and the others who died, and then Darby went to bed.

Kobe Bryant was one of those people, like Princess Diana or Robin Williams, who seemed to live in a different sphere from the rest of us, and their deaths remind us that no one is immune to the fragility of life. For Angelenos, it was like losing a landmark, as if all the palm trees had fallen, or the Pacific Ocean had gone still. As my son and countless others have said, for anyone who played or watched basketball, Kobe was a fixed point, a standard against whom everything was measured.

Gianna Bryant was neither landmark nor fixed point; she was a beautiful, talented 13-year-old girl on her way to play basketball. Later that night, I learned that Alyssa Altobelli, another beautiful, talented 13-year old, was also killed in the crash, along with her parents, John and Keri Altobelli. By the time she left for class, Darby knew that too. (We would later learn that Payton Chester, 13, and her mother Sarah Chester were also killed.) She hoped her teachers would somehow acknowledge the loss; I told her she could ask for a moment of silence in her first class if they didn’t.

Kobe Bryant, the NBA MVP who had a 20-year career with the Lakers, was killed Sunday when the helicopter he was traveling in crashed and burst into flames in the hills above Calabasas. His daughter Gianna, 13, was also on board and died along with seven others.

I want to say I will think of Gianna, Alyssa, Payton and their parents, their families, every day I am fortunate enough to watch my own 13-year-old basketball player go off to school or practice, every night I know she is asleep in her bed. I want to say that it shouldn’t take the deaths of a star and two young players to make us appreciate the mundane wonder of daily life, with its battles over homework and bedtimes and all the long drives to far-flung tournaments or whatever outside interests our children have.

But sometimes it does.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.