The Grateful Dead were in a state of flux. ‘Wake of the Flood’ gave them new life

- Share via

If there is any constant in the story of the Grateful Dead, it’s transition. From sine qua non of American psychedelia, to folk-rock deity, jam band progenitor, disco Dead and Top 40 sensation, there was seemingly no pivot the band couldn’t navigate in its 30 years.

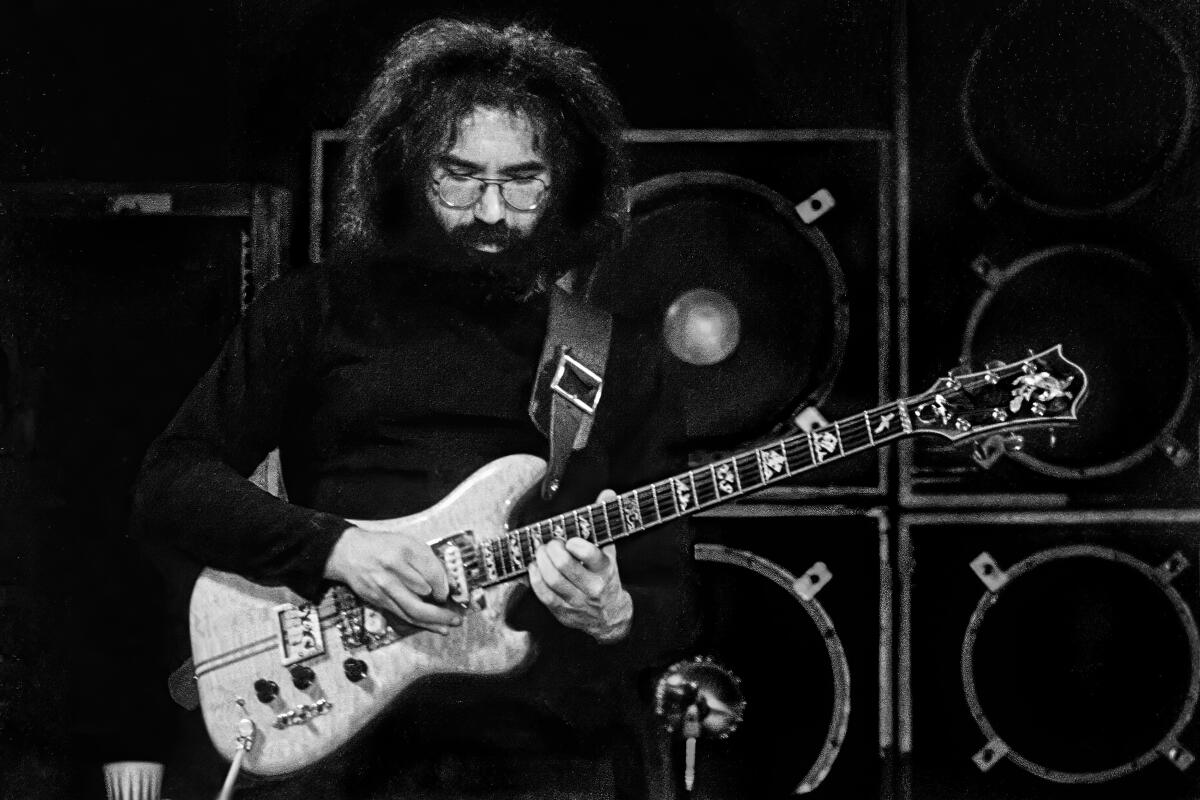

The Dead’s sixth studio album, “Wake of the Flood,” released 50 years ago on Oct. 15, is a high mark of the band’s ability to recast itself, pushing on in the wake of adversity and grief, propelled by the infectious creative spirit of singer-guitarist and band leader Jerry Garcia. “I was the surfer, riding that wave of excitement,” says drummer Bill Kreutzmann.

In conjunction with the anniversary, Rhino Entertainment has released a remastered version of “Wake of the Flood” on CD and varying vinyl editions. The set includes previously unreleased demos of “Eyes of the World” and “Here Comes Sunshine,” written by Garcia and lyricist Robert Hunter. They were recorded by Garcia and distributed to the band ahead of a show at Stanford University on Feb. 9, 1973, when they debuted many songs that ended up on “Wake of the Flood.” The set also includes a live recording of a show at Northwestern University held shortly after “Wake” was released.

“He was really on fire about a new era of the Grateful Dead,” Donna Godchaux says of Garcia. The singer and her husband Keith Godchaux joined the group in the fall of 1971, she on backing vocals and he on piano. Kreutzmann recalls a phone call he received from Garcia, who’d recently met the Godchauxs and had invited Keith to play with him in a studio as an informal audition. “I’d never heard Jerry so excited,” Kreutzmann remembers. “He said, ‘You gotta get down to the studio. You won’t believe this guy. I can’t lose him; I can play anything I want and he’s right there with me.’”

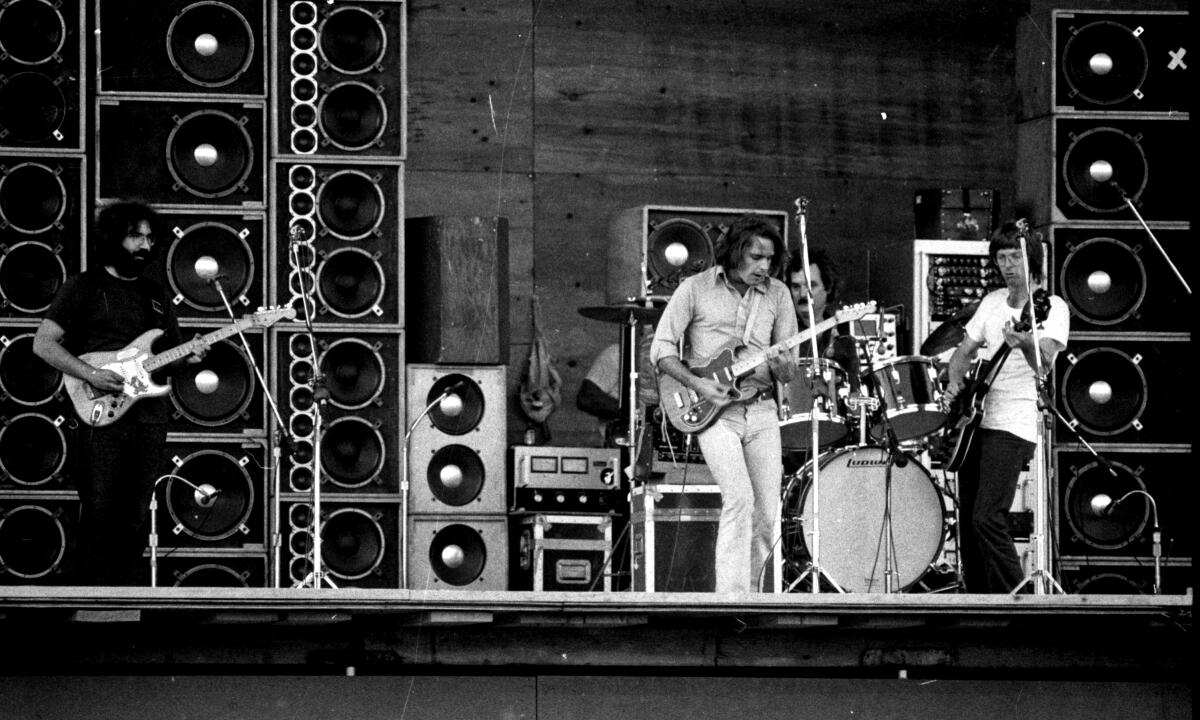

The Godchauxs performed with the lineup of Garcia, Kreutzmann, Bob Weir (rhythm guitar, vocals), Phil Lesh (bass, vocals) and Ron “Pigpen” McKernan (organ, harmonica, vocals) on an overseas tour that was immortalized as the live album “Europe ’72.” Mickey Hart, the band’s percussionist, had taken a break amid a struggle with heroin. His father, Lenny Hart, who briefly managed the band, had also disappeared with a large sum of the Grateful Dead’s money.

On opening night at the $2.3-billion Sphere concert hall, the visuals projected onto the high-def walls behind and above U2 were a show unto themselves.

Then, shortly after the European tour, in March 1973, McKernan died of a gastrointestinal hemorrhage related to alcoholism. In a 1972 issue of Rolling Stone, Garcia credited McKernan with his shift from acoustic jug band to electric guitar, which prompted the formation of the Warlocks, the band that became the Grateful Dead. “It was Pigpen’s idea,” Garcia said. “He’d been pestering me for a while, he wanted me to start up an electric blues band. That was his trip.”

“Sadly, they had to move on,” Godchaux says. “And how could you without Pigpen, who was largely the source of the Grateful Dead? It’s hard for me to talk about this, but they had to reorganize and it really took place in the making of ‘Wake of the Flood.’” Piling on to the complex obstacles of tragedy, the Dead had parted ways with Warner Bros., which released its first nine studio and live albums, and decided to start its own label, Grateful Dead Records.

“This was the first time everything was on us,” says Dan Healy, the Grateful Dead’s longtime audio engineer who worked on many of their albums and oversaw the band’s live sound for decades. “There were no excuses. We had nobody to blame. We were sort of writing the book of how it was going to be for us for the future.” It was also the band’s first studio album since the landmark “American Beauty,” released in 1970.

Shortly after their appearance at the Summer Jam at Watkins Glen, where an estimated 600,000 people poured onto a racetrack in rural New York to watch the Band, the Allman Brothers Band and the Grateful Dead — a show that is legendary among Deadheads — the group convened at the new Sausalito branch of the legendary Record Factory studio, where Sly Stone famously took up temporary residence. “It was very woodsy. A real earthy feeling to it,” Kreutzmann says. “A carpenter [local artist Dave Richards] had made basically a jigsaw puzzle out of little pieces of wood; he made all these geometric designs that went around the walls and ceiling. It looked far out, and it sounded far out.”

According to Healy, the studio was “hot rodded” with a state-of-the-art recording console that pushed the Dead into a new era of high-quality audio. “If you have a vinyl pressing of the original release of that record, it’s an audiophile’s dream,” he says. “It is fabulously clean sound.” The studio also had bougie amenities such as a jacuzzi, private chefs, guest houses, a tennis court and its own boat docked nearby. “It was the era of cocaine dealers and dumptruck loads of cocaine; there was a lot of that going on,” Healy says.

Godchaux was no stranger to a studio setting. A native of Florence, Ala., the largest city in the quad known as the Shoals, she was a hired gun in the area’s historic recording scene, singing backgrounds on hit songs such as Elvis Presley’s “Suspicious Minds” and “When a Man Loves a Woman” by Percy Sledge. But this time, she truly felt like a part of a band. “It was a magical time because all the gates were open,” she says.

Garcia and Hunter had been on a writing streak, and created seven of the album’s nine songs, including the yearning ballad “Stella Blue,” mystical reflection “Eyes of the World” and gospel-steeped “Row Jimmy,” which became fan favorites and Dead canon. Remarkable, too, was Weir’s 13-minute, three-part “Weather Report Suite,” with lyrical assistance by singer-songwriter Eric Anderson, which prophesied future progressive Dead compositions such as “Terrapin Part 1.” “Let Me Sing Your Blues Away,” the album’s second track, featured Keith Godchaux on lead vocals for the first and only time with the Dead. It was a song he’d written with Hunter, and one that the band struggled to play because, Donna Godchaux says, “The chord structure was so unusual.”

For Kreutzmann, “Row Jimmy” stands out because it was an exercise in taking “different forms and putting them together to make the form we were trying to get to,” he says. It was difficult for him to play at first because it “didn’t have an obvious groove to it.” He describes the song as akin to a “slow reggae” with “a double time and a half time all strung together in ballad form, kind of.” In other words, its execution was no easy feat.

“Wake of the Flood” also marked a major presence of auxiliary instruments played by guests, including violin, trumpet, saxophone, trombone, harmonica and timbales. Martin Fierro had played with Garcia on the freeform jazz fusion album “Hooteroll?” and blew a saxophone solo on “Let Me Sing Your Blues Away.” Doug Sahm, who played 12-string guitar, recorded with Healy with the Sir Douglas Quintet, and would open eight dates with the Dead during a September 1973 tour as a solo artist. Fiddler Vassar Clements was a ringer in the newgrass scene and played with Garcia in Old & in the Way, one of many side projects. Healy compared their month in Sausalito to a family gathering: laid-back, supportive and joyful. “I used to tell Jerry he was an artistic enabler,” he says. “He could get artists to feel so good about doing what they do. They would forget about their own insecurities. He was a good encourager.”

Donna Godchaux agrees. “It was just like the world had opened up. Not just for me and Keith, but for the entire band.”

Critical response to “Wake of the Flood” was mixed. Robert Christgau, writing for the Village Voice, called it a “deceptively demanding combination of ‘American Beauty’ and ‘Aoxomoxoa’” but said Hunter’s lyrics were “more of the old karma-go-round, with barely a hook phrase to come away with.” Rolling Stone’s critic wrote, “Despite an impressive stylistic smorgasbord, slick overdubbed production and the best intentions in the world, to my ears this band still sounds generally sick, usually woozy, and often afflicted with perpetual head cold, twinges of sinus trouble, you name it.” Still, the album peaked at No. 18 on the Billboard 200, the band’s highest-charting album to date.

Some fans have speculated that the title “Wake of the Flood” — a line from Hunter’s “Here Comes Sunshine” — indicates a tribute to Pigpen, particularly the prominence of the word wake. Kreutzmann says that the album wasn’t “inherently made that way,” but that doesn’t mean the loss wasn’t difficult. “There’s none of them [deaths within the Dead family] where it gets any easier,” he says. “You don’t get used to that.”

This was especially true on Aug. 9, 1995, when Garcia died of a heart attack, ending the Grateful Dead as the world knew it. Since then, the surviving core of the band has played in several spinoffs centered around the Dead’s music, to varying degrees of success. In November 2012, Phil Lesh & Friends played “Wake of the Flood” in its entirety at a show in Montclair, N.J. And the last eight years have seen an unmistakable Deadaissance due to the popularity of Dead & Company, composed of Weir, Hart, Kreutzmann, pop star John Mayer in Garcia’s role, bassist Oteil Burbidge and keyboardist Jeff Chimenti.

For all of its significance in the story of the Grateful Dead, many agree that “Wake of the Flood” hasn’t received the love it deserves. Healy blames the record industry of the early 1970s, which, he says, didn’t approve of the Dead going independent, and tried to quash the album. “It was almost like organized crime in a way,” he says. David Lemieux, the Dead’s audiovisual archivist and legacy manager, thinks that “American Beauty” was simply a hard act to follow, that the general listener was expecting more songs like “Truckin’.” “Once the songs started becoming a real part of the live repertoire, hearing them in that context made people realize that these are some interesting songs,” he says. “I certainly consider them so.”

Regardless of its wider status, “Wake of the Flood” was an important bridge to a near-future Dead that made beloved albums such as “From the Mars Hotel,” “Blues for Allah” and “Terrapin Station,” and live shows that are widely circulated on bootlegs and considered some of the band’s best. Today, Kreutzmann says he loves the “Wake” album and still plays its songs live with his band Billy & the Kids.

“It was incredible to have the luck of Hunter writing songs like that, and Jerry putting the music to them,” he says. “I was very fortunate to be in that place. We all were.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.