- Share via

Just after 11 a.m., the old man rolls in, a few minutes late, and smiles as he asks for a few minutes more — “I’ve got some huevos coming,” he explains. Then he walks to the piano in the corner of the lounge. As soon as his hands touch the keys, the melody that fills the room is broken, playful, beautiful, unmistakably his, as if he’s signing his name across a blackboard: Neil Young is in the building.

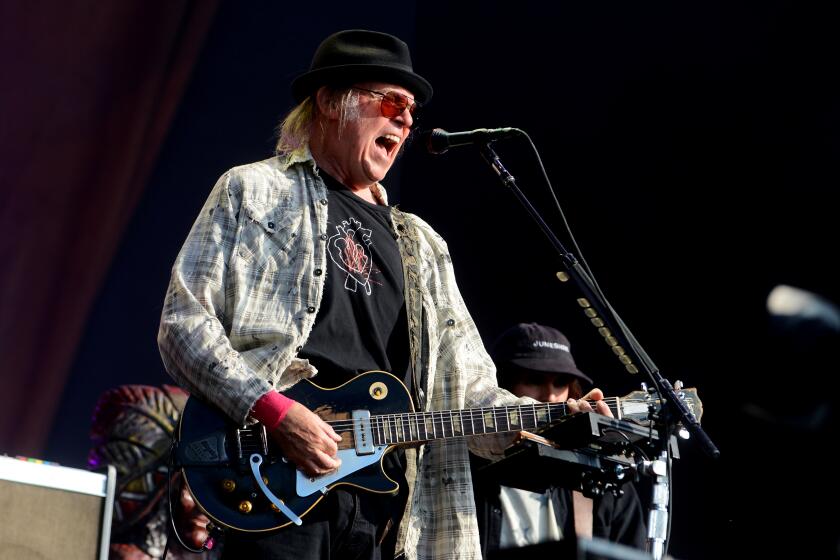

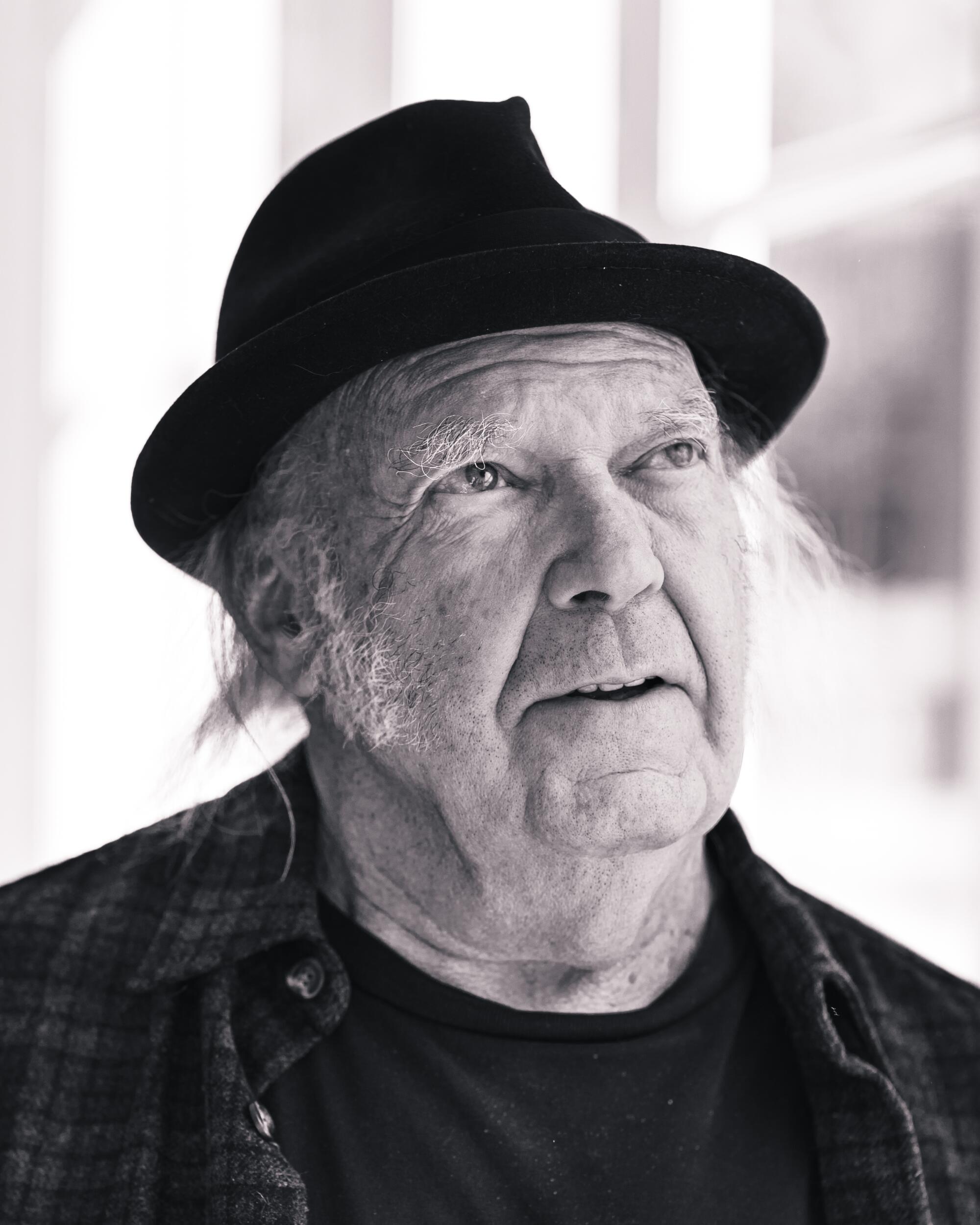

That building is Shangri-La, Rick Rubin’s studio, high on a hill overlooking Zuma Beach. Today Neil Young is wearing dark flannel, dark gray jeans and comfy-jumbo walking sneakers, a black fedora over long and fine gray hair. The pin in his hatband says “CANADA.” He smells like a guy with part of a joint in his pocket. He is a week or so shy of 77 and when viewed in profile, he looks like the portrait they’d use if they put Neil Young’s face on the obverse of the loonie. Straight on, he has the same wild eyes he’s always had, the same mad-bomber smile.

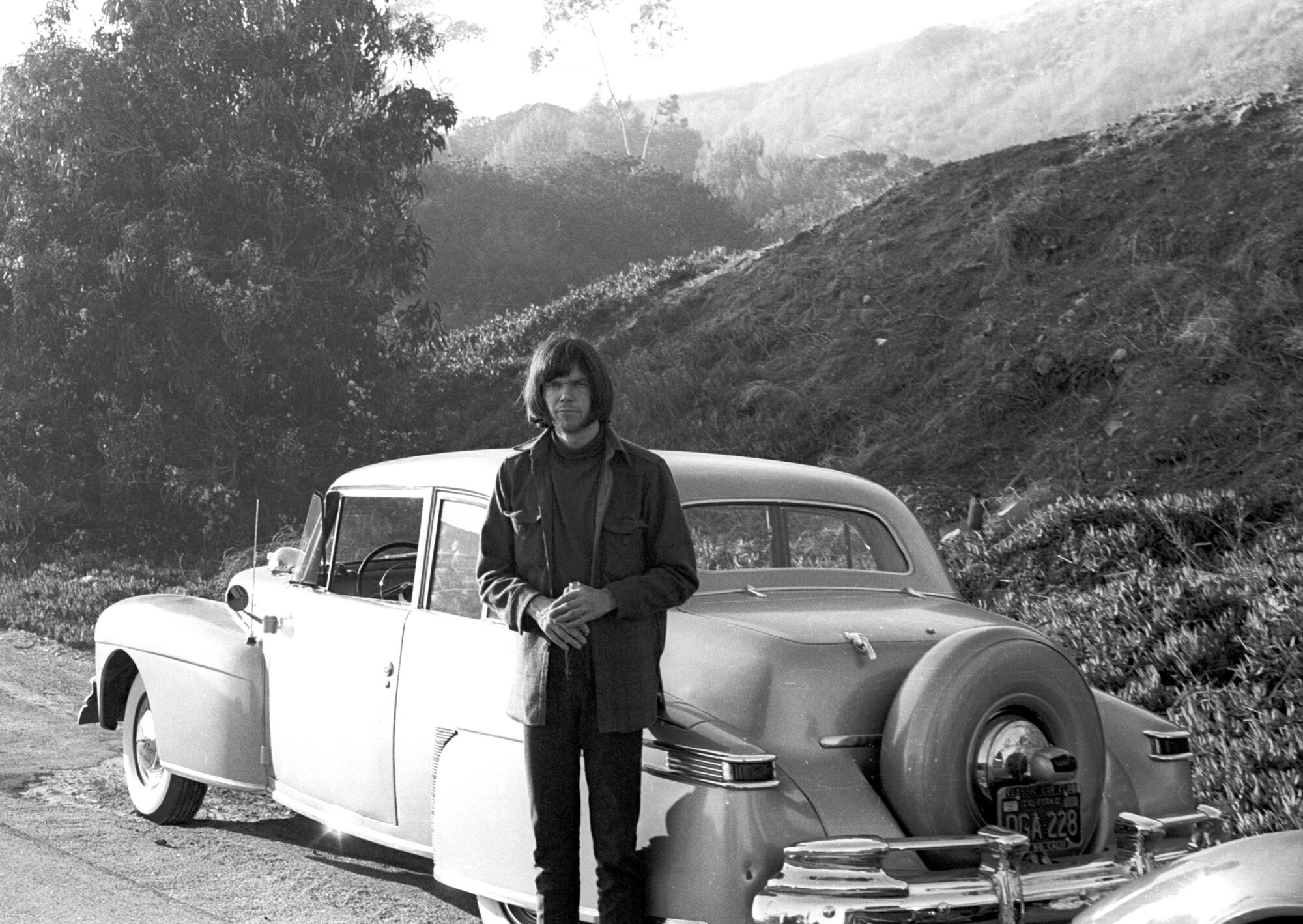

Young hasn’t lived in Malibu since 2018, when he and wife Daryl Hannah lost their house to the Woolsey fire. But the place looms large in his mythology. He spent time here in the ’60s, with Buffalo Springfield; he and Crazy Horse recorded the rollicking, transcendent “Zuma” here in 1975. Back then, Shangri-La was the Band’s studio and clubhouse, and when Young was living a few minutes up the PCH on Sea Level Drive, he’d drop by sometimes to hang out and play music. (As far as he can recall, none of it was ever recorded, which may suggest how good a time was had by all.)

Young and Rubin (who bought Shangri-La in 2011) have been friends for years, and they’ve recorded together before, but the new “World Record” — Young’s 42nd studio album, which came out this week — is the first actual Young release to credit Rubin as producer. Rubin describes his involvement as a happy accident. “I was booked to be on the other side of the planet recording a different project, and the universe created obstacles to keep that from happening,” Rubin said in an email interview. “Neil called just as my travel schedule changed. Divine intervention.”

When the moment presents itself, you go with it; this has always been the Way of Neil, and it still is. Most of the songs on “World Record” began as tunes that came into Young’s head while walking his dogs in Colorado last winter. “It was incredible because I was just walking along, not thinking about anything,” Young says. “Every day there’d be a new melody. It was coming out of the air — and that’s unusual.” He captured the earliest demos using the “funky little pixelated camera” in his flip phone, then wrote lyrics — fast, in about two days.

By the time he and the members of Crazy Horse — bassist Billy Talbot, drummer Ralph Molina and guitarist Nils Lofgren — convened at Shangri-La, Young had shared his demos with the band in a series of FaceTime calls. But he arrived with no preconceived ideas about how the record would sound. “The songs took Neil where they wanted to go, and that’s what you’re hearing,” says Rubin, who notes that while recording took about three weeks, most of the takes on the album were captured during the first week.

As on many of Young’s 21st century albums — from 2015’s agribusiness-bashing “The Monsanto Years” to 2019’s “Colorado” — the dominant subject here is the environment, whose plight worries Young now more than ever. But this time around, he’s singing more about what might be possible — clear skies, clean water, a world without war. A lifetime ago, Young’s sneer anticipated punk; pushing 80, he dares to dream of humanity united and nature healing, as if time has robbed him of nothing except his cynicism.

You’ve said that this album began with melodies you found yourself whistling while walking across a field. Where were you walking?

A daily walk that I would take, of maybe three to four miles, at 8,500 feet or so, in the Rockies, in the snow.

Any particular destination?

We kind of had a place to end because somebody would meet me there, and there was a rough time that I would probably arrive, and if I didn’t, they would come looking for me. We had a plan.

How often do songs come to you when you don’t have an instrument in your hand?

I have no method. [Laughs.] When it happens, I stop doing everything else. Whatever’s going on — if I have a melody in my head that won’t go away, I’ll figure out a way to get it down. To me, that’s a gift I can’t ignore.

But was it unusual for you to suddenly get all these songs at once?

I wasn’t even thinking. It just came out so naturally. It’s almost like someone else wrote it. Like a ghostwriter did this. And I never questioned it.

I had all the melodies, and then around the full moon of April, in two days, I wrote all the lyrics. And then never changed anything. Not a punctuation mark, not a word, nothing. That’s very unusual.

One of music’s greatest living showmen returned to the site of perhaps his most famed concert as part of his Farewell Yellow Brick Road tour.

What’s funny is that even though you were doing it in this deliberately accidental way, there’s a thematic cohesion to these songs. You made a record once called “Living With War”; this one could be called “Living With Climate Change.” Is that just what’s on your mind these days?

There’s a lot of that in my head. A lot of people are saying that we’re in the end times of our civilization. I definitely feel it all around me. The climate is changing so fast — we don’t even realize how fast it’s happening. And I think that’s the root of a lot of the anger that we’re feeling. It’s all fear. I don’t think we’re really scared that other people are coming in and f— everything up for white people. I think everybody’s scared of the same thing — what’s happening on the planet.

So I love the idea that everybody realizes this and comes together. I can [picture] world leaders talking together on the same stage, telling the world what’s happening. Everybody, let’s stop competing with each other and just try to save our asses and save the planet.

That’s what’s interesting about this record. There’s every reason to be cynical and pessimistic about the subject matter, but you’re singing about hope.

Oh yeah — I feel a lot of hope. Things could turn quickly. [But] we need to step back and love Earth every little way we can. Electric cars are good, but they’re not the answer. The worst contributor to climate change is factory farms. We have a lot of people, but we don’t need to do that to feed them. We need to do that to make a fortune feeding them.

Instead of piling pigs on top of each other in a metal building with fans and antibiotics so that we can have Oscar Mayer wieners, we need to let the pigs go out, walk around, make holes in the earth with their feet. So when it rains, there’s little holes and the water goes in. There’s all kinds of reasons why that [helps]. And then the pigs s— everywhere. So that goes into the earth too. Then instead of having dry dust, you put your hand in it and it’s got worms in it, right? It’s alive.

We’re just doing it all backwards because we thought we could make a fortune. And we did make a fortune. But now we’ve got back payments to make. [Laughs.]

You’re going to be 77 in a week or so. You sound more like a hippie than you did at 22.

I take that as a compliment. We just have to do the natural thing. And that’s really what “World Record” is about. If we go forward together, we may be able to make it. That’s the strength we’ve never exercised.

Whether it’s factory farming or all the work you’ve done advocating for high-resolution digital music, it seems like you’re trying to make people see the same truth — that short-term gains have far-reaching consequences. With digital, it was about sacrificing sound quality to sell more iPods and iPhones …

There’s 5,000 songs on this device, and they all sound like s—. Every one of them. Because you got maybe less than 5% of the data that’s required to hear it. In the analog generation, every part of the sound was there. That’s what analog is. It’s not divided up into little pieces. It’s ugly, what digital did. Ugly.

Not to get morbid — long may you run — but you’re turning 77. If any of these changes come to pass, do you imagine you’ll be here to see them?

Life is a funny thing. I can’t tell. I’m glad to be here today, and I know that I’m not as solid as I was before in some ways. In other ways I’m more solid than I was. Like, part of me says I never want to tour again. I just don’t feel like it right now. But on the other hand, what if I do feel like it? So I don’t have any ideas on that right now. But if I was gonna tour, it would only be in places that served food from family farms. I do know that. So I’m working with people to try to make that happen, but it hasn’t happened yet. So I’m not happening until that happens. And maybe I won’t want to do it by then. I may be doing something else. I just wrote another book. I’m editing it now. It’s called “Canary.”

Is this your sci-fi novel?

Yeah. That’s been done for a year and a half. [Laughs.] It’s so big. I can’t even describe it.

Young is no stranger to taking on powerful interests, whether it’s music gatekeepers, soft-drink companies or his own record label.

You’ve put out a lot of previously unreleased music over the last decade or so — two Neil Young Archives box sets and counting, plus a few actual albums that never saw the light of day. In preparing that material for release, what have you learned about yourself, or your process?

I’m glad that I kept moving. I couldn’t finish some things because I was into something else.

When you’ve put things aside, is that usually the reason?

It’s usually because I was distracted by something new. But sometimes I didn’t want to put it out because I was feeling it too much, and didn’t want that out there at the time in my life. That was what “Toast” [recorded in 2000 and 2001, unreleased until July of this year] was like. And it’s subtle. You can listen to “Toast” and not even really realize what’s going on in it. But “Toast” was a very personal record for me, and I didn’t put it out for a long time. There’s a few more like that in [the vaults]. I have a great thing coming, probably next year, called “Mirrorball Live,” with Pearl Jam. That’s a movie and an album. And there’s more I can’t remember. I’m making the list up now for [Archives] “Volume IV.” “Volume III” is completed and in production.

I was advised not to dwell on it too much, but there’s also a 50th anniversary edition of “Harvest” coming out.

Yeah. Fifty years since I made that record.

You once wrote that “Harvest,” and specifically “Heart of Gold,” put you “in the middle of the road.” Do you still feel that way about it?

Well, the success of that record. “Harvest” was a good record, but it wasn’t any better than many of the other records. Just another record. There are other ones that are far more compelling. But it had a moment. Everybody was ready for me to make “Harvest,” and I made “Harvest” and then, wow, look what happened. Then we moved on. Gotta get away from that. That’s not where I want to be.

You put together “Harvest Time,” the documentary that comes with the new “Harvest” reissue. What was it like to watch your 26-year-old self being interviewed while making this record? Did you recognize that guy? His answers, his thoughts?

Some of them. I was very young, just figuring out what’s going on in my life. And I had just had my mind blown. I had just put out “After the Gold Rush,” and I was making “Harvest” and making a film. So there was a lot going on. But it’s just another record. Just another record.

I think [the movie] tells a good tale of life at the time. And everybody’s in it. Carrie Snodgress, my son Zeke’s mom, is in it. Jack Nitzsche’s there. All of [Young’s “Harvest” band] the Stray Gators — Tim Drummond, Kenny Buttrey, Ben Keith, they’re all there. [“Harvest” producer] Elliot Mazer’s there. These people are all gone. Everyone I just mentioned.

How does that feel, realizing that?

I don’t know. I don’t know what to think about that. It’s gonna happen to everybody, eventually. I understand I could turn a corner and something could happen to me — but I’m not thinking about that. I want to enjoy the day and go swimming this afternoon. I fell while I was walking about 3 1/2 weeks ago and hurt my knee. And it’s still mending. So I want to get in the pool, use my knee, get it figured out.

You gave up smoking pot around the time you wrote your first book, “Waging Heavy Peace.”

I did, but then I started smoking it again. [Laughs.] And then I gave it up again. I’m much clearer when I don’t smoke.

Quitting didn’t seem to affect your productivity at all. Does it affect your art?

I don’t think so. I enjoy the art when I’m high. And that’s fun. That’s the best thing. Weed is here for a reason. It isn’t here just because it’s no good! [Laughs.] And it’s in stores now, if that’s proof of anything. I hardly ever go in those stores, ‘cause you have to give them your ID, and I can’t do that. But I can get it. It’s around.

Yeah, I imagine it’s been a while since you’ve had to worry about that.

No, I don’t have trouble with that. There’s no problem there. Me and my buddies, we can all get it. I can always call Willie. He might have some. [Laughs.] Don’t you love Willie Nelson? He’s gonna be 90. He’s having his birthday concert next year. I’m gonna be at that.

And he’s still playing!

He plays great. Willie’s like a flower. He’s just continually growing and changing.

You pulled your music off Spotify earlier this year because you felt it was complicit in spreading vaccine misinformation.

Yeah.

A lot of people pointed out at the time that you and Joni Mitchell, who also pulled her music from Spotify, were both survivors of polio, a disease that’s been largely eradicated by vaccines. Did that make it a more personal decision for you?

What bothered me was I heard doctors talking about how people were dying because of misinformation, and that one of the big sources of it was this one show on Spotify. And I just woke up and called Frank [Gironda, Young’s manager] and said, “Frank, take my s— off Spotify.” And everybody thought I was kidding. But they realized I wasn’t very shortly after that. It didn’t make any difference to me that half of my income from streaming comes from Spotify. Or used to. [Laughs.]

Now it comes from other places because people still have to have the music. Plus everywhere else you go to get it, it sounds better. Amazon, you can say what you will about the people working in the [warehouses] and all that stuff. Fact of the matter is, they’re putting high-res digital music on the marketplace. That’s good for music. I’m here for the music.

I guess it’s always about figuring out where to draw that line, right?

Yeah, that’s right. Or about changing where it is.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.