- Share via

“Weird Al” Yankovic quit his most recent day job in 1983.

By then he was a few years out of college and his self-titled debut album was already in stores. But he was still working a minimum-wage gig at the radio network Westwood One, where his duties included daily post-office runs. One day he pulled a Billboard magazine from the mailbag.

“I opened it up,” he says, “and there’s my song” — it was “Ricky,” his “I Love Lucy”-themed parody of Toni Basil’s 1982 hit “Mickey” — “on the chart.”

“Ricky” would rocket all the way to No. 63 on Billboard’s Hot 100 and no further — but the fact that it had charted at all still felt like a sign.

“I think that very day I gave my notice,” Yankovic says. “I said, ‘Well, maybe I should be full-time Weird Al, see how this thing pans out.’”

When asked when being full-time Weird Al started to feel like a viable career, Yankovic, who just turned 63, says, “I think about three months ago.”

Which is, y’know, a joke. Yankovic is far and away the most successful comedy recording artist of all time. He’s sold more than 12 million albums. His last album, “Mandatory Fun,” was the first comedy album in history to debut at No. 1 on the Billboard 200 — and the first one to top that chart at all since Allan Sherman dropped “My Son, the Nut” in 1963. It went on to win Yankovic his fourth Grammy Award — of what are now five — in 2015.

He hasn’t released another full-length album since that happened. He knows how that looks.

“It is kind of ironic that I had my first No. 1 album and then decided, OK, I’m done,” he says, laughing. “It’s kind of a nice mic drop.”

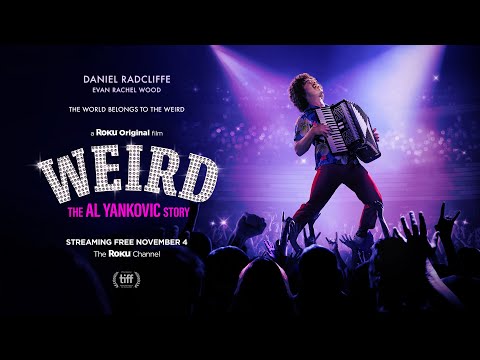

It wasn’t an intentional one. He’s stepped back to focus on other endeavors, like “Weird: The Al Yankovic Story,” a hilariously counterfactual sendup of the prestige-biopic genre, which premieres on the Roku Channel on Nov. 4.

But he’s also recording less and less these days because writing hit-song parodies has become a tougher racket. His first EP came out in 1981, the same year MTV debuted; for years, the video channel defined who was famous and what was a hit song, and Yankovic wrote parodies accordingly, sending up whatever came down the monocultural pike — synth-pop, heavy metal, hip-hop, grunge and two successive generations of Cyruses.

In the age of the micro-niche, it’s harder to know what songs to make fun of.

“There’s still major superstars and big hits,” Yankovic says, “but it’s not as easy to discern as it was a couple years ago.”

In the ’80s, pressure made him prolific.

“I felt like I had to keep grabbing that brass ring,” Yankovic says, “because I was scared to death. It was drilled into my head that because I do comedy music I’m a quote-unquote novelty artist, and historically novelty artists have been one-hit wonders.”

Nearly 40 years ago “Weird Al” Yankovic began building his fan base the old-fashioned way: radio.

Instead Yankovic has defied that conventional wisdom by recording dozens of hits — not to mention outlasting the cultural relevance of many of the artists he’s parodied, from Greg Kihn to El DeBarge to Crash Test Dummies to Taylor Hicks to Iggy Azalea.

This may be the weirdest thing about Weird Al in 2022, nearly 40 years after “Ricky”: He’s become a legacy artist.

Bring his name up in the right room, and comedy elites of a certain age become young boys again, bowing down to the memory of a mustachioed man who showed them what was possible just by strapping on an accordion and playing songs about bologna.

“There are people — I also think about Robin Williams in this way — that were really key to my development when I was younger,” says Tim Heidecker, a preteen Weird Al fanatic who grew up to co-create shows like “Tim and Eric Awesome Show, Great Job!,” on which Yankovic recurred as Uncle Muscles, a creepy variety-show host. “And then you get a little older, and a little more cynical, and a little more too-cool-for-school, and you kind of dismiss them. And then later you realize how important they were and how much you still value what they did for your understanding of music and comedy and everything.”

Will Menaker, co-host of the leftist comedy/politics podcast “Chapo Trap House,” says, “The seed of what would become ‘Chapo’” was planted when he first saw “UHF,” Yankovic’s 1989 movie about a man of dubious prospects who is given control of a marginal TV station. “I rented it on VHS and watched it like 10 times over a weekend — like, wore out the heads on the VCR rewinding it over and over again,” Menaker says. “If Weird Al hasn’t already gotten the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor, he deserves it. He’s a national treasure.”

His appeal now transcends generations. Evan Rachel Wood, who plays a highly fictionalized version of Madonna in “Weird,” says she learned about Yankovic from her mother. Not long ago, Wood took her 9-year-old to one of Yankovic’s shows for the first time.

“He’s not somebody who uses swear words or does things that aren’t family-friendly,” Wood says, “yet it somehow always feels like he’s pushing the envelope and being weird and grotesque. I think that’s one reason he’s been able to stay in it so long.”

Barry Hansen, the DJ far better known as Dr. Demento, was the first person to play Yankovic’s music on the radio. The song was “Belvedere Cruising,” an ode to Yankovic’s ’64 Plymouth. It was March 1976, and Yankovic was still a student at L.A.’s Lynwood High School. He went on to be the most-played artist in the history of Hansen’s show, which started out in syndication on radio and continues online. For most novelty songwriters, making it into Demento’s rotation is the pinnacle; for Yankovic, it was only the beginning.

“It’s inspiration and perspiration,” Hansen says when asked why Yankovic beat the odds. “His inspiration didn’t run out after one big hit, and he works very, very hard at it. He and Frank Zappa are the two people who worked hardest at making funny music that have ever lived — Spike Jones worked hard at it, but not as hard as Weird Al.”

A TRADITIONAL WEIRD AL show is a multimedia event — props, costumes, video, Yankovic riding around on a Segway. But on his current tour, Yankovic and his band are playing sit-down shows, and the set list is made up almost entirely of his originals, not his hit parodies.

Yankovic’s originals skew toward observational comedy and the vividly grotesque; some of his sad-sack protagonists — like “Skipper Dan,” a depressed thespian who’s “read my Uta Hagen and studied the Bard” but has to drive a Jungle Cruise boat at Disneyland to make rent — could almost be Randy Newman characters, although Newman’s never sung about stapling bagels to his face. Hardcore Weird Al devotees have been waiting decades to see these songs performed live, but in the interest of calibrating the expectations of more casual fans, Yankovic is calling this one the Unfortunate Return of the Ridiculously Self-Indulgent, Ill-Advised Vanity Tour. It was supposed to start last year, before COVID-related delays intervened.

“My original plan was not to tour in 2020,” Yankovic says, “and that worked out great. But I was planning to hit the ground running in 2021, and that didn’t work out so well.”

The tour began in April and finishes Saturday at Carnegie Hall in New York City. On this mid-September night, the venue is the Santa Clarita Performing Arts Center at College of the Canyons, where the main room seats 886 and upcoming headliners include Richard Marx and something called the Perondi’s Stunt Dog Experience.

In a few hours, every seat in this theater will be filled. The audience will include a few young kids, because the golden age of Weird Al is 12, but it will be mostly made up of men who have not been 12 for quite a while, except maybe on some internal, spiritual level. They will be wearing Hawaiian shirts or novelty T-shirts broadcasting their pop cultural affinities (Lando Calrissian, Primus, the fictional “Breaking Bad” chicken chain Los Pollos Hermanos). At least one of them will be wearing one of those kilts that’s designed to double as a tool belt, known as a utilikilt.

Whether they all would self-identify as nerds is hard to say, but when Yankovic’s opener, veteran comedian Emo Philips, begins a joke by saying, “There’s probably no one here who was not bullied,” he will have to wait out a long and seemingly cathartic laugh before adding, “… today.” (Later, during his own set, Yankovic will say that if someone had told him he’d end up, in his 60s, riding around on a bus with Philips, he would have said, “Yeah, you’re probably right.”)

At the appointed time, Yankovic will lope onstage and tell the crowd that it’s great to be here in Santa Clarita, “the very place where they shot the last season of ‘Reno 911,’” and explain that tonight, “We’re gonna play a bunch of extremely unpopular songs.”

He and the band will not play “Ricky” or “Like a Surgeon” or “Eat It,” but they will play originals written in the style of everyone from the White Stripes (“CNR,” a mythic blues about “Match Game” goofball Charles Nelson Reilly) to AC/DC (“Young, Dumb and Ugly”). Yankovic will play cowbell and vibraslap and tambourine and a high-tech Roland FR-4x accordion, which he mostly uses to digitally reproduce the sound of instruments other than the accordion, except on the zydeco song about his girlfriend falling in love with Eddie Vedder.

In Santa Clarita, Miles Jay will play bass, sitting in for his father, Steve Jay, who’s sick. Steve Jay has been playing with Yankovic for 40 years, as has drummer Jon “Bermuda” Schwartz. Because he didn’t join until the early ’90s, keyboardist Rubén Valtierra is still considered the “new guy” in the band and gets hazed accordingly. When Yankovic introduces Schwartz in Santa Clarita, he talks about the day they met — Sept. 14, 1980, which was also the day Schwartz backed up Yankovic for the first time, playing drums on Al’s accordion case during a live radio performance — whereas when Yankovic introduces Valtierra, he simply says, “We met on Grindr.”

At the end of the two-hour set, after the traditional set-closing cover — in Santa Clarita it’s “Mama Told Me (Not to Come)” — they’ll play a few parodies, including “Amish Paradise” and a singalong “Yoda,” and then it’ll be over until the following night, when they’ll do it all again in Thousand Oaks.

Beatles fans will never agree on what is the band’s finest album, but ‘Revolver’ began to replace ‘Sgt. Pepper’s’ as the consensus choice in the 1990s.

Right now, though, it’s an hour or so before showtime, and Yankovic is sitting in a folding chair backstage, talking about his last foray into cinema.

“UHF” is now the kind of cult classic people write oral histories about; in 1989, it was not quite as appreciated. When I tell Yankovic I saw the film the day it opened, he replies, “You’re the one!”

“Orion Pictures had built me up,” Yankovic says. “They said, ‘This is getting incredible test scores. We’re gonna be doing movies every year with you’ — and I thought, ‘I guess I’ll only be releasing movie soundtracks from now on, because I’m gonna be a movie star.’”

He laughs at his own hubris. After the movie bombed, he says, “I won’t say that I fell into a spiral of depression, but I was pretty bummed out.”

Years later, in 2010, Yankovic and writer-director Eric Appel made a fake trailer for an overwrought and self-serious Weird Al biopic with “Breaking Bad’s” Aaron Paul playing Al and comedian Patton Oswalt as Dr. Demento. It was an instant viral hit on Funny or Die; Yankovic would play it between songs at his shows while he went backstage to change costumes, and fans would ask, in earnest, when the movie was coming out.

Yankovic had no plans to expand on the trailer, in part because he figured it would be a tough sell. “Historically,” he points out, “movies like this do not do well at the box office. I mean, ‘This Is Spinal Tap,’ one of the greatest movies of all time. ‘Walk Hard.’ ‘Popstar.’ All these faux movie biopics — and I love them all, they’re brilliant — did not do well.” The “UHF” experience had made him cautious, he says, laughing: “I didn’t want to come back after 33 years with another bomb.”

But then came a new wave of real rock biopics, including “Bohemian Rhapsody,” which played like a parody without any jokes and somehow won a few Oscars. The more Yankovic thought about the biopic genre, the riper it seemed for parody, and one morning about 2 ½ years ago, Yankovic woke up and sent an email to Appel, suggesting that maybe they should expand that fake trailer into a full-fledged fake movie.

Appel is 42 — a second-generation Al fan whose mom showed him “Eat It” on MTV when he was 4 years old, which led to him seeing “UHF” in the theater (“I made my grandpa take me to it, and I think he fell asleep. He was like, ‘I fought in a war— what are you making me sit through?’”) and eventually to a career in comedy, as well as directing jobs on “New Girl,” “Silicon Valley” and “Brooklyn Nine-Nine.” When he and Yankovic started writing together, Appel was impressed by his partner’s seriousness.

“I come from an improv background,” Appel says. “It’s very loosey-goosey. Al has a mathematical brain. Our writing sessions together weren’t just a big, goofy pitch-fest where you’re bouncing around the room. There was quite a bit of quiet contemplation.”

Part of the reason Yankovic’s song parodies work so well, Appel points out, is that they’re usually note-perfect re-creations of the source material, right up until Al starts singing about food or ducks or surgery. “That’s the approach we took to the movie,” Appel says. “The only way to do a Weird Al biopic is to make it feel like a really dramatic biopic but the words are different.”

The result is a precise satire of rock biopics as a genre and the absurd liberties these films take with truth and time, particularly when it comes to the creative process. Both Appel and Yankovic mention the scene in “Ray” where Jamie Foxx’s Ray Charles, arguing with his pregnant mistress, comes up with the hook to “Hit the Road Jack” in a matter of seconds; in “Weird,” young Al hears his roommate say something about lunchmeat, and within the hour, Al’s new song “My Bologna” is on the radio and climbing the charts.

Daniel Radcliffe says it was this absurdly over-the-top approach that made him want to do the film. When the script came to him, he says, “I was confused. I was a Weird Al fan, and I was like, ‘That’s cool and very flattering that he would think of me. But surely there are people that are closer to him physically,’ and all those things. And then I read the script and I was like, ‘Oh, right — it doesn’t matter.’ I was thinking, ‘I’m probably going to say yes to this’ from around Page 4.”

IN REAL LIFE, YANKOVIC upends every cliché about damaged, angry, approval-hungry comedians. On Marc Maron’s “WTF” podcast, traditionally a forum for the airing of funny people’s psychic wounds, Yankovic was the rare guest with almost nothing to declare — notwithstanding the loss of his parents, who died of accidental carbon monoxide poisoning in their home in 2004, when Yankovic was 44.

The movie invents a more pathos-rich dramatic arc. Movie Al survives an abusive, accordion-smashing father, dates Madonna and eventually squares off with Pablo Escobar.

But it’s not all lies. Yankovic really did grow up sheltered, raised by conservative parents who didn’t approve of Dr. Demento. In college, he really did stay home writing parody songs instead of partying. He really did go on to become wildly, expectation-defyingly successful. And it really did all start with an accordion salesman knocking at the Yankovics’ door.

In real life, Yankovic notes, the salesman actually offered him a choice between accordion or guitar. If he’d chosen the latter, Yankovic says, “I doubt I would’ve had a career at all. The reason Dr. Demento played my stuff back when I was just sending him tapes that I recorded in my bedroom was because he thought it was a novel thing for a teenage kid to be playing the accordion and thinking he was cool.”

After college, Yankovic worked for Dr. Demento for a little while, and Hansen got a glimpse of Yankovic’s creative process.

“He would research his songs,” Hansen says. “He carried around a big, blue loose-leaf notebook everywhere he went for a while, until laptops were a thing. He would write down ideas for songs. Fragments. And he’d go to the library. Like when he wrote the song ‘I Want a New Duck,’ he told me he spent an afternoon in the library just researching ducks.”

Yankovic’s early work also had a deranged energy to it. The original 1979 version of “My Bologna,” cut in a men’s bathroom at Cal Poly, feels spiritually connected to L.A. punk from around the same time. Yankovic says he “definitely felt a kinship” with punk and new wave. In their own way, both he and the punks were puncturing the self-seriousness that crept into rock ‘n’ roll as the form grew more gentrified.

But when I mention to Yankovic that rock critic Chuck Eddy once referred to Al’s parody “Smells Like Nirvana” as “the only honest rock criticism that Nirvana ever received,” he winces a little. He points out that “Smells Like Nirvana” — which Kurt Cobain is on record as having loved, even though it portrays him as an inarticulate marble mouth — was a rare example of a Yankovic parody that directly mocks the original artist. Yankovic would rather leave criticism to critics and mockery to “morning zoo” hosts.

“Some people who do song parodies, their whole thesis in the song is, ‘This band sucks. This artist sucks. This song sucks,’” Yankovic says. “That gets old after a while.”

Yankovic isn’t legally obligated to obtain the permission of the original artist before releasing a parody, but he asks for it anyway; the fact that he almost never targets performers’ foibles has to be part of why they say yes. His approach is gentle and silly and also self-deprecating; part of what we’re supposed to laugh at is the ridiculousness of Yankovic, white and nerdy, harnessing the power and pathos of a pop song to explore his own white-and-nerdy concerns.

But the world has changed significantly in the four decades since Yankovic started releasing music. The borders separating the inoffensive from the actionable have been repeatedly redrawn. I ask Yankovic if he’d feel weird about impersonating Black artists on record if he were starting out today. He covers most of his face with his hand while this question is being asked, as if to keep his immediate reaction private, and when he moves his hand away, his smile is back in place.

“That’s a really tough question, and you can add that to the list of reasons why I’ve been a little reluctant to do [more] parody songs,” he says.

“I don’t rail against PC culture and all that because I think when somebody is accused of being politically correct, that usually just means they’re being sensitive to other people’s feelings.”

Yankovic stopped playing his Michael Jackson parodies, “Eat It” and “Fat,” after the documentary “Leaving Neverland” came out in 2019 because he didn’t want people to have to think about child abuse and Jesus juice while watching a comedy show. He isn’t sure he’ll ever play those songs again. (It’s also been years since the R. Kelly parody “Trapped in the Drive-Thru” appeared in his set list.)

He still plays “Albuquerque,” an 11-minute-plus shaggy-dog story-song in the George Thorogood tradition, but he pauses midway through to contextualize his use of the word “hermaphrodite,” affirming that language is supposed to evolve, that certain words that seemed funny in 1999 aren’t funny anymore — unlike the word “Albuquerque,” which will always be funny.

ALSO, AT THE SANTA Clarita show, after playing “Buy Me a Condo,” a 1984 reggae song about a Rasta who cuts his dreads and turns yuppie, Yankovic dryly remarks, “That concludes the cultural-appropriation portion of the show,” and I will wonder if my line of questioning has made Yankovic feel bad, and will feel bad about it.

Like Heidecker, I loved Yankovic and then got too old or too cool for his parodies. But his body of work made me curious about pop music and how it worked, how words worked; I might not have been a writer without it otherwise. Yankovic may not have written many songs that qualify as “personal,” but my relationship with his body of work is personal nonetheless.

I’m not alone in that. The fans who line up for the after-show meet-and-greet in Santa Clarita clearly feel the same way. In a post-COVID world, “meet-and-greet” means the fans gather backstage and a guy from Yankovic’s road crew herds them into an orderly line: “It’s like taking Communion — Catholics, help the non-Catholics.” Each person gets a chance to stand on one side of a plastic barrier while Yankovic stands on the other and tour photographer Kamal Asar takes a picture of them pretending to organically yuk it up together. Later Asar will go in and Photoshop out the barrier in each photo so it looks like Yankovic and the fans have actually met and greeted each other without a sneeze guard between them. (When asked if this takes all day, Asar — who says Yankovic is the nicest musician he’s ever traveled with except for maybe Brad Delp from Boston — replies, “Only the first eight hours.”)

After two rootsy pandemic albums, ‘Midnights’ picks up right where 2014’s ‘1989’ and 2017’s ‘Reputation’ left off.

Pre-pandemic, a lot of people, especially women, would want hugs; this would make things take forever. And sometimes, on nights like this one, the third date of a four-night run, Yankovic will keep his interactions brief to save his voice. But sometimes he’ll talk to fans as long as they want to hang around. And over the years, they’ve told him all kinds of emotional things.

“Some people have told me that I’ve prevented them from committing suicide because they were in a really bad, dark place, and they listened to my music and it snapped them out of it,” Yankovic says. “Or it helped them deal with a toxic relationship or any horrible situation you can imagine. My music, for them, was a light in their world, even though I ostensibly am doing silly, goofy music.”

He says this like it’s information he does not quite know what to do with. No one confesses anything painful at the Santa Clarita show. But a pregnant woman in a “Welcome Baby Thomas” T-shirt lines up with her husband to take a photo they plan to use as a birth-announcement picture — Yankovic points at her stomach across the barrier, comically agog at the miracle of life. A guy with curly hair and a mustache who looks remarkably like a young Weird Al walks up and says, “Hey, Dad,” and Yankovic calmly replies, “Hey, Mr. Yankovic.”

Men tell him they’ve seen him live many, many times, and he’ll tell them they look familiar. They say that they’ve been listening to him since ’92 or ’79 or since they could barely walk, and Yankovic will act like he’s never heard this before. They show him their custom-painted Weird Al Vans, and they beg him not to retire. They tell him they’ve been dreaming of this moment since they were 8 years old, and Weird Al smiles at them and says, “Me too.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.