In Tulsa, the new Bob Dylan museum reconsiders the legacies of an icon and a city

- Share via

TULSA, Okla. — In his liner notes to “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan,” the singer saw what was heading toward him back in 1963 and put up his guard, writing, “I do not care to be made an oddball bouncin’ past reporters’ pens.”

It’s just as well, then, that he skipped the soft opening of the Bob Dylan Center, in Tulsa, Okla.

The museum was thrumming with invited guests last weekend, just a few days before it opened to the public on May 10. NPR and the Minneapolis Star Tribune and “CBS Sunday Morning” were here, looking for a good line on why Dylan matters. There were Dylanologists galore, folks ready to argue with what the recorded tour averred. Patti Smith was taking selfies. Musicians John Doe and Taj Mahal and comedian-podcaster Marc Maron puttered between exhibits.

“I thought it was just great,” Maron said of the museum. “Whatever your context is, whatever portal you use to see into Dylan, it’s transcendent.”

Pete Townshend on writing for Roger Daltrey (“not easy”); losing Keith Moon and John Entwistle; and his new Audible Original, ‘Somebody Saved Me.’

Dylan, now 80, is famously given to reinvention and loath to explain himself. Put his life and work in a museum, that final resting place ideas too often go when they’ve already gone everywhere else? How could it work?

There isn’t a lot to compare the Dylan Center to. In contrast to Graceland, another single-artist institution, the center is more of a cultural space and less of a cult space. Visitors walk past a 16-foot-tall metal gate welded by Dylan himself, past a room showing a video about his life. Then you are in the downstairs exhibition area, focusing on his songs. Interactivity is encouraged, and the songs move in and out of your head as you wander the floor. There is a jukebox that Elvis Costello packed with songs by Dylan or numbers that shaped him. And there is a reading nook with books curated by Tulsa native Joyce Harjo, U.S. poet laureate and the center’s inaugural artist-in-residence.

Upstairs, in the rest of the 29,000-square-foot space, is a gallery devoted to numerous glances at Dylan’s biography: a bag of fan mail from 1966, Bruce Langhorne’s Turkish drum that inspired Dylan to write “Mr. Tambourine Man,” a postcard from Pete Seeger saying he never really minded when Dylan “went electric.”

The center holds approximately 100,000 items, including letters, notebooks, bootleg recordings, leather jackets. Even given all that stuff, it feels important to explain that what one encounters isn’t so much stuff but words and ideas. The core of the exhibition space is a focused look at a handful of songs by Dylan (“Jokerman,” “Tangled Up in Blue” and “The Man in Me,” among them), spotlighting how they changed as he worked on them and how they kept changing after he put them on record.

Museums are places full of stuff. Yet this new institution in Dylan’s name is not a repository of stuff: What’s on view is the creative process — how one of the most unpredictable forces alive built his art and keeps at it today. A lot of visitors to the center are going to end up thinking about the work they do, whether or not they write, paint, sing or dance. A quote from Dylan greets the eye upon entry: “Life isn’t about finding yourself or finding anything. Life is about creating yourself and creating things.”

Mark Davidson employs the word “velocitation” to describe what he’s feeling the weekend before the Bob Dylan Center opens to the public; it’s what drivers who have been pounding down the freeway can feel when they suddenly find themselves motoring through a town at normal speeds. Time seems to stand still.

Davidson, the curator and director of the Bob Dylan Archive, has been pulling 12-hour days for weeks leading up to the opening.

The center came into focus in 2016 when billionaire Tulsa oilman George Kaiser heard from a New York rare-book dealer through his Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser had purchased the archives of Oklahoma-born folk singer Woody Guthrie in 2011 and helped create the Woody Guthrie Center in Tulsa’s Arts District.

The book dealer said Bob Dylan was interested in selling his archive to Kaiser, in no small part because Dylan’s legend involves his early worship of Guthrie. He sang his hero’s songs as a teenager growing up in Hibbing, Minn., and just after he arrived in New York City in 1961 visited Guthrie as he was dying of Huntington’s disease in New Jersey.

Kaiser bought the Dylan archive for a reported $20 million and brought Davidson on in 2017. Dylan found more stuff and sent it that year, and Davidson and his staff have been unpacking and getting ready for the opening for five years now.

Davidson explains his philosophy of trying to appeal to three overlapping groups simultaneously: skimmers, swimmers and divers. That is, casual visitors who may barely know Dylan’s name; fans who have his music on their hard drive; and the fanatics who think they have heard it all before.

To illustrate, Davidson describes how the center was contacted by a collector who went to college with Dylan in Minnesota in 1959. He said he had a picture of Dylan in a suit at a campus performance that he wanted to donate. “So, for a lot of people, that will be a nice picture of Bob among other early photos. For other folks, they’ll know it must be at the University of Minnesota. For somebody like Bill Pagel” — a hardcore Dylanologist, Pagel famously has bought Dylan’s two childhood houses — “he’s studied the bricks of different buildings on campus, and he will know from looking at the wall behind Dylan in the photo, ‘Oh, this was taken at the Hillel center.’”

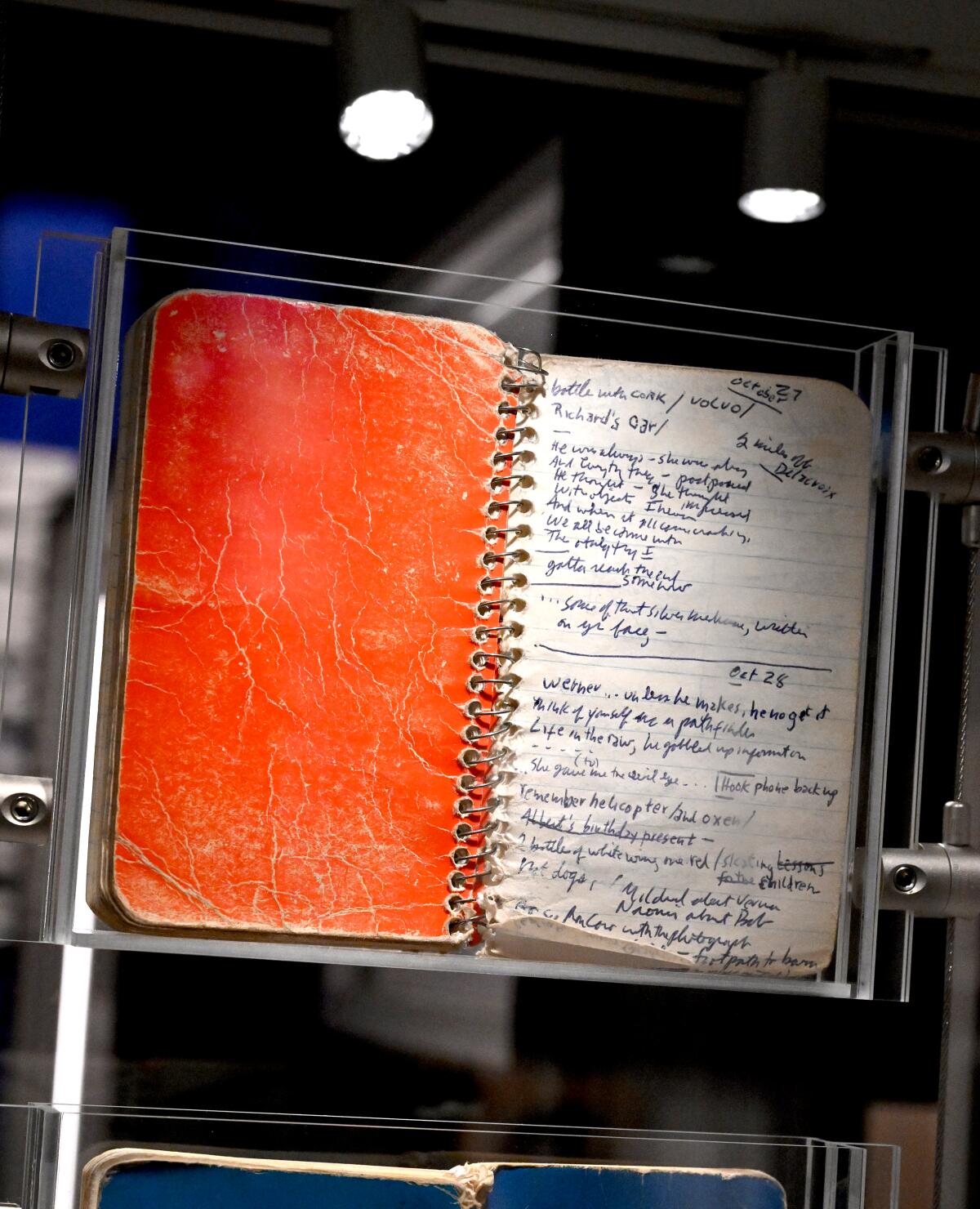

One fulcrum of the exhibition space is the legendary “little red notebook” in which Dylan wrote and rewrote the songs that in 1975 became “Blood on the Tracks,” an artifact that writer Mark Jacobson has fittingly called “the Maltese falcon of Dylanology.” The notebook was said to have been stolen from Dylan and to have turned up at New York’s Morgan Library and Museum. Now it is on display at the center, along with two other notebooks that show Dylan revising and writing alternative versions of some of his most celebrated songs.

“Who knows?” said Davidson. “Maybe there are more notebooks. Our hope is that discoveries will continue to happen — that he keeps opening closet doors, boxes, whatever. We want everything to be in Tulsa.”

A few blocks from the center is Cain’s Ballroom, a vintage 1920s dance hall. For three nights last week, one musician who influenced Dylan, Mavis Staples, and two who learned from him, Smith and Costello, played shows and invoked aspects of Dylan’s sweeping presence.

Costello came with guitarist Charlie Sexton (who often plays with Dylan) and offered a roof-raising “Like a Rolling Stone.” He told a story about scoring a ticket to see Dylan in L.A. in 1978, at the very beginning of the Englishman’s career, and, to his surprise, being whisked into Dylan’s green room. Dylan came out and cordially said, “I’ve heard a lot about you.” Costello responded, “I’ve heard a lot about you too.”

Dylan himself was nowhere to be seen at Cain’s or anywhere else nearby. “I don’t know if I’ll ever meet him,” said Davidson, the man who has spent years lovingly archiving Dylan’s things.

Steven Jenkins just recently became director of the center, and he points out that Dylan has a new book coming out on songwriting and is in the middle of a tour. He’s thinking about now, not then. If Dylan wasn’t comfortable with what they have done, Jenkins feels he would know.

“He just played Tulsa two and a half weeks ago. He didn’t call us up for a coffee and a bagel. Didn’t ask if the walls were the right color. I hope if he comes in, under a hoodie and a baseball cap, he picks up on the sense of respect and the sense of play, our juxtapositions that we hope let people see something of the man.”

Tulsa worked because Dylan liked the idea of the museum being in the heartland, as he told friend and historian Douglas Brinkley. He also responded to the Native American presence in the region. Dylan is interested in the country’s Indigenous roots; at Tuesday’s public ribbon-cutting, “I Shall Be Released” was sung in Cherokee.

But there are few direct flights to Tulsa from New York or L.A., and although the city is on Route 66, it’s off the beaten path. Can the museum make a go of it long-term? Jenkins pinpoints that as a key challenge.

The essential goal, he said, is “getting the word out and having our work rise to a level of excellence that’s undeniable [and] in keeping with the man who is at the heart of this.”

There is the nearby jewel of a music venue, Cain’s Ballroom. There is impressive support from Kaiser and the city. Brinkley thinks the city itself is ideal for what Dylan and the planners behind the center want to achieve. “True, Tulsa is the beginning of the west, but it is on the edge of north, south, and east. There’s no better crossroads city in America; Tulsa is a sort of amalgamation of our country in its best ways.”

Brinkley is a deep admirer of Dylan’s work. “It falls comfortably alongside Melville’s and Walt Whitman’s — or Aretha Franklin’s and Bruce Springsteen’s.” Therefore, “Bob Dylan fans from around the world will make the pilgrimage to Tulsa, the same way you go to Glacier National Park in Montana or visit the Jamestown colony in Virginia.”

Access is not the only issue the Dylan Center knows it must deal with. There’s also the living history of Tulsa, a place where scarcely 100 years ago white Tulsans waged racial assault on Greenwood, Tulsa’s “Black Wall Street” district. Hundreds were murdered, more than 1,250 were burned out of their homes, and then the city never spoke of it for decades, until Greenwood almost disappeared from its conscience. Recent years have seen Greenwood reemerge as an important history for America to grapple with.

It happened within walking distance of where the Dylan Center is today. “I say this not to say, ‘Hey, we’re woke,’” said Jenkins, “but that this is in a special place and a special time. We can’t turn a blind eye to the history and sociocultural context in which we find ourselves.”

Steph Simon, a rapper and cultural force in Tulsa, spoke with me by phone on the morning the center opened to the public. The Kaiser Foundation and the Dylan and Guthrie centers provided support that helped launch the “Fire in Little Africa” project, which used dozens of rappers and singers from Oklahoma to mark the centennial of the Tulsa Race Massacre.

Simon talked of the need to celebrate Black heroes from the city, like Charlie Wilson of the Gap Band. “Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie … they’re not engaged with heavily in the Black community,” Simon explained at an even pace. “People know who they are, but [Tulsa native, NBA player and Motown recording artist] Wayman Tisdale is our Bob Dylan.”

Davidson describes what he calls the Tulsa Experiment. It entails work done by the George Kaiser Family Foundation to break the cycle of poverty in Oklahoma, with early childhood education programs and programs that offer alternatives to incarceration for women. It also involves creating gathering places like Guthrie Green, a commons area in front of the Dylan Center, as well as the Tulsa Arts Fellowship, “Fire in Little Africa” and other projects.

Along with being an archivist, Davidson is a musician and music scholar, and he invokes a term he says comes from gamelan music, a sonic surge called a blossoming. “We are watching a blossoming going on here in the Arts District this very weekend.” He gulps a little air.

“Now the work really begins.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.