Appreciation: 10 essential songs of ranchera legend Vicente Fernández

- Share via

No one would’ve held it against Vicente Fernández if he had flamed out early in his career. After all, the singer had the weight of a nation placed on him when he debuted in 1966.

Mexico’s three greatest ranchera icons — Jorge Negrete, Pedro Infante and Javier Solís — had died at the height of their careers in the previous 13 years. The man who wrote their greatest hits, José Alfredo Jiménez, was slowly drinking himself to death. Other stars of the genre — Luis Pérez Meza, Antonio Aguilar, Miguel Aceves Mejía — were popular but couldn’t capture the zeitgeist the way Negrete, Infante, Solís and Jiménez had.

Fernández would. The title of his second album, released in 1967, set those expectations from the start: “La Voz Que Usted Esperaba.”

The Voice You’ve Been Hoping For.

Over the next 40 years, Fernández released hundreds of songs that secured his spot as the fifth head alongside Negrete, Infante, Solís and Jiménez on ranchera’s Mt. Rushmore. In some way, he eclipsed them. When we think of the archetypal ranchera singer — a man in a gleaming charro suit and immaculate mustache whose machismo swings from braggadocio to pathos in seconds — we now think of the man whom fans simply know as Chente.

The following is a glimpse into how Fernández turned into another of his nicknames — El Ídolo de México. Mexico’s Idol. These are not my favorite Chente songs and definitely not yours, but it chronologically tracks one of the greats and shows what made him so consistently spectacular.

“Tu Camino y el Mío,” 1969

Fernandez’s first albums found him trying to rein in his titanic voice but not yet having the maturity or skill to do so. Think of those as his Randy Johnson years. He began to fulfill his potential with this song. “A bunch of ungrateful memories/A letter that I haven’t read,” Chente roars, as mournful horns back up his sadness. He communicates the depressed frenzy of the protagonist — this is a guy who can’t get over the woman who left him and just doesn’t know how to move on — with a calm, deliberate delivery. But what pushes him over the edge in misery is the chorus, where Felipe Arriaga, one of the few singers who was ever able to match Chente’s baritone — joins in. Together, the two lifted “Tu Camino y el Mío” (“Your Way and Mine”) to its heights and let Mexico know that Fernández had a good shot of living up to his hype.

“Volver, Volver,” 1972

The 1972 album “¡Arriba Huentitlán!” (“Long Live Huentitlán!”, the name of Fernández’s hometown) was Fernández’s first great release. The album starts off with “El Jalisciense,” a galloping paean to the traits and cities of his native state of Jalisco. But the most famous track from “¡Arriba Huentitlán!” is “Volver, Volver.” Once again, Arriaga helps his compa on the chorus to this weeper, one so heart-wrenching that no less an authority of melancholy than Harry Dean Stanton sang it for one of his final film roles, in 2017’s “Lucky.” The song starts with a dirge-like organ, moves on to weeping horns backed by simple, strong guitar strums, and crawls toward the titular, titanic plea of “Volver, Volver” — return, return. That particular refrain is now as much a part of Southern California Mexican American Spanish as “Doyers.”

“El Rey,” 1972

Chente covered some Jiménez songs — “El Jinete” on his first album, “Las Botas de Charro” in 1979 — but none were better than this one, a defiantly existential cri de coeur in the same theme as “My Way” (which Jose Alfredo wrote before Paul Anka — just saying). “The King” is one of the few times that a singer bested Jiménez’s original rendition, and it’s such a part of Mexican American life that it played at AT&T Stadium in Dallas during a Cowboys game Sunday — and the crowd sang along and cheered.

“La Ley del Monte,” 1975

Despite becoming Mexican royalty, Chente was always a country boy at heart. His songs about horses (“El Moro de Cumpas”), roosters (“Hoy Platiqué con Mi Gallo” — more on that in a bit), and the village life always found him at his most exuberant, especially in peliculas campestres — rural comedies. “The Law of the Hill” was included in the soundtrack for the film “El Hijo del Pueblo” (“The People’s Son”) and tells the story of a man who had scratched his name and that of his beloved on a maguey plant after a night of canoodling, only to see her break off that stalk when they broke up. The following spring, all the magueys on the hill sprouted stalks that bore the graffiti that declared their eternal love, a bit of magical realism that’s also one of the great reveals in ranchera history.

“Los Mandados,” 1977

Chente was a political conservative, a longtime supporter of Mexico’s long-ruling PRI party who infamously sang at the 2000 Republican National Convention. Yet he was someone who well knew the struggles of his fans in the United States and marveled at their resolve as they tried to come into el Norte, legally and not. Hence, this morality play ringed by accordion, a novelty in ranchera music but one used here to evoke the U.S.-Mexico border, where norteño music reigns.

In “The Orders,” Chente assumes the role of a mojado — a “wetback” — who freely crosses in and out of the United States — “300 times, let’s say,” until the hated migra finally captures him and beats him up. Chente’s character not only isn’t afraid — he sues the government for his abuse. In an era when undocumented immigrants are frequently portrayed as pitiful and helpless, here is a proud, unabashed one who revels in mocking U.S. immigration policy and sounds even more radical today than he did over 40 years ago.

“Hoy Platiqué Con Mi Gallo,” 1986

“Today I Talked to My Rooster” — need any further clue as to how country this song is? But what could easily have been a problematic celebration of cockfighting (which Chente did in other songs) instead turns into a subtle critique of the bloody sport and its fans. “Why did you take such good care of me,” Chente’s rooster asks him, “if today, you’re throwing me to Death?” When Chente blames a “damned bet” that has put his life in danger, the rooster has heard enough. “I’m going to save you,” he tells Chente, and quickly kills his opponent, but not before that rooster delivers a mortal blow. At the end, Chente warns his audience, “You should never betray a friend” — a line worthy of PETA.

“Mujeres Divinas,” 1988

A slow, sultry ballad that finds Chente at his most meta. He’s a singer in a cantina whispering songs of lament to the heartbroken backed by muted trumpets and arpeggioed guitars when a gray-haired gentleman asks him to stop. The two argue about who’s been hurt more, then Chente concludes, “Women, o such divine women/There’s nothing else to do except to adore them.” He repeats it at the end, and concludes with a surprising sob — the macho defeated.

“Perdón,” 1993

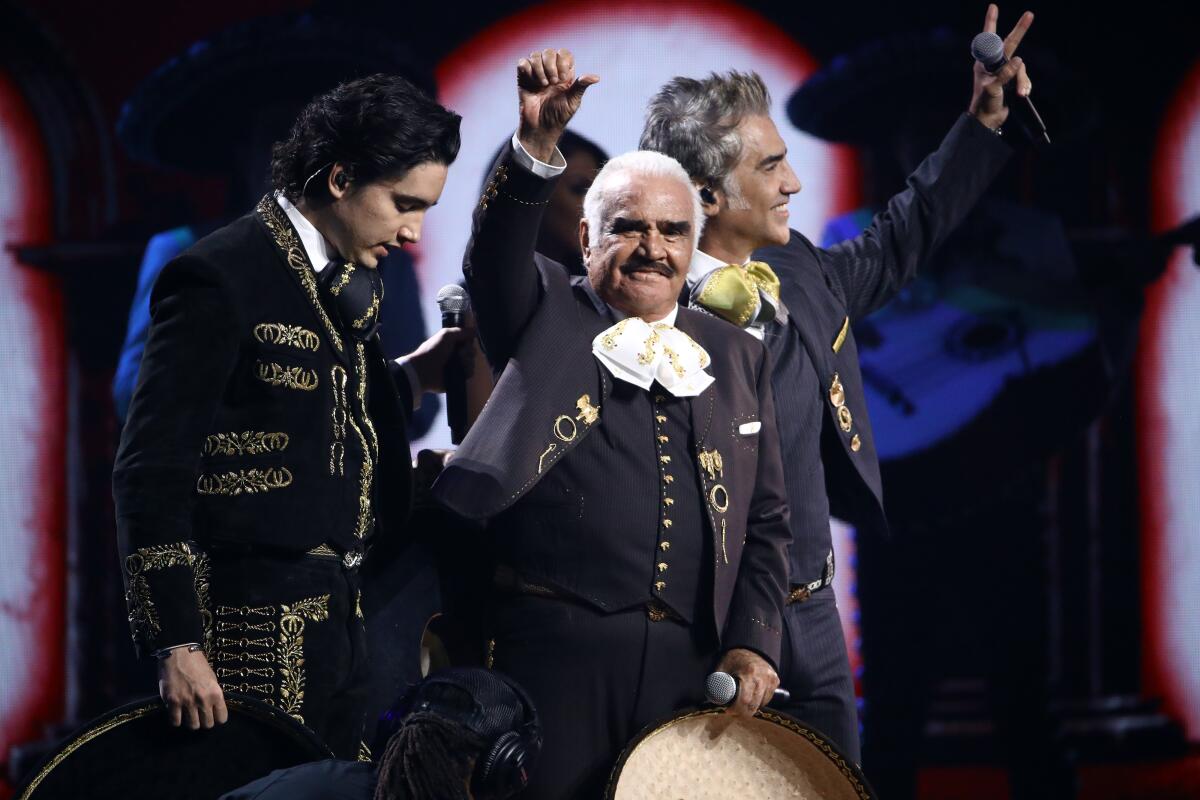

Fernández recorded duets with everyone from Vikki Carr to Celia Cruz, but his greatest partner was his son Alejandro, nicknamed “El Potrillo” — the Foal, a son with a voice almost as mighty as that of his papi. In this apologetic track — originally recorded live for the album “L´astima Que Seas Ajena,” then retracked years later — father and son match each other roar for roar before Alejandro steps back to let his dad have the solo. Halfway through the live version, the audience applauds, and an obviously happy Chente proclaims, “That’s my son!” before yelling at him “Get over here!” and telling the crowd “very handsome ... what a stud!”

“Me Voy a Quitar de En Medio” 1998

Chente’s songs were iconic enough that he never went out of style, but his career found a second wind in the late 1990s gracias to theme songs to smash telenovelas. That subgenre started with “I’m Going to Get Out of the Middle” from “La Mentira” (“The Lie”), a favorite of my late mother. I still remember the initial excitement of the opening credits: That saw an elder Chente riding a horse past the front of a hacienda as elegant as ever. His voice can no longer hit the high notes as before, but now he finds his vibrato delivering sensitive notes better than ever, aging like a fine añejo.

“Estos Celos,” 2007

Perhaps Chente’s last true masterpiece, this song found him covering another legendary singer-songwriter, Joan Sebastian. With an atypically sunny start punctuated by warm horns and twinkling guitars, followed by sudden musical breaks and a rush of guitar strums, “These Jealousies” showed a master who was never afraid to experiment all the way until the end. It’s slowly becoming a constant of the mariachi repertoire, joining all the songs above and dozens more.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.