After 30 years as Hollywood’s coolest film composer, Danny Elfman still has something to prove

- Share via

If Disney ever wanted to reboot “Toy Story” as a horror franchise, they’d do well to tap the curiously creepy collection that famed film and TV composer Danny Elfman keeps in his East Hollywood recording compound.

Animators could do a tracking shot through the enclosed loading dock, into Elfman’s studio, and be greeted by the man himself, who’d introduce his little buddies: a pair of fist-sized, shrunken human heads that occupy space on a table in the corner of a cavernous entry room.

Protected in glass display cases a few steps away from a similar case housing an original Jack Skellington doll from “The Nightmare Before Christmas” (Elfman provided the singing voice of Skellington, as well as the film’s songs and score), the shriveled noggins sit among various Victorian medical devices, detached mannequin hands, busts of clowns, doll parts and other macabre curios that constitute the life-long Angeleno’s aesthetic.

Recently Elfman, who just turned 68, opened his studio doors for an extended conversation on his life’s work as a composer — a résumé filled with Oscar, Emmy and Grammy nominations, but best known for his 16 film scores for director Tim Burton and for the theme song to “The Simpsons” — and how all that informed “Big Mess,” Elfman’s first solo album in more than 30 years, which comes out via Anti-/Epitaph on June 11.

During the afternoon, Eflman variously describes himself as insecure, competitive, hyperactive, weird and obsessive. At one point he pulls up his shirt to reveal six-pack abs and a torso dense with tattoos.

“I thrive on negative energy,” he says. “I was reviled by every other composer, understandably. I was a jerk from a rock band,” referring to his punk-era art-rock band Oingo Boingo. That disdain, he continues, was “the best thing that could have happened to me because every single score I did for Tim was all about, ‘I’ll show those motherf—. Give me your hate. All you motherf— are going to be imitating me in your next score.’

“I’m a little bit like Godzilla,” he says. “You try to throw an atomic bomb on me and it just makes me stronger.”

“Big Mess” is the closest Elfman has come to making a rock album, and it’s as filled with sonic incitements as his compound is with grimly alluring paintings and images by Joel-Peter Witkin, Mark Ryden and Henry Darger. Spanning 18 songs and nearly 75 minutes, it’s a fiercely political work filled with bombastic peaks and strikingly meditative valleys that focuses on the internal and external strife caused by living in a country torn apart by hate, racism, ignorance and corruption.

“We reached a point in 2020 where I felt like we were living a dystopian novel version of America,” he says. “Trumpism is literally ‘Two plus two equals five because Trump says it’s five.’ I didn’t think that was possible. The big mess was all around me.”

How fans of Elfman’s filmic work receive “Big Mess” depends on whether or not they’re willing to fully immerse themselves in such a beast of a project. As if anticipating the reaction, the artist apologizes five times in the first song, “Sorry,” and again in the second song, “True,” a work whose opening stanza concludes with the line, “Why do I live in hell?”

With Renée Zellweger in attendance, Rufus Wainwright performed Judy Garland’s immortal ‘Live at Carnegie Hall’ album with a small ensemble at Capitol Studios.

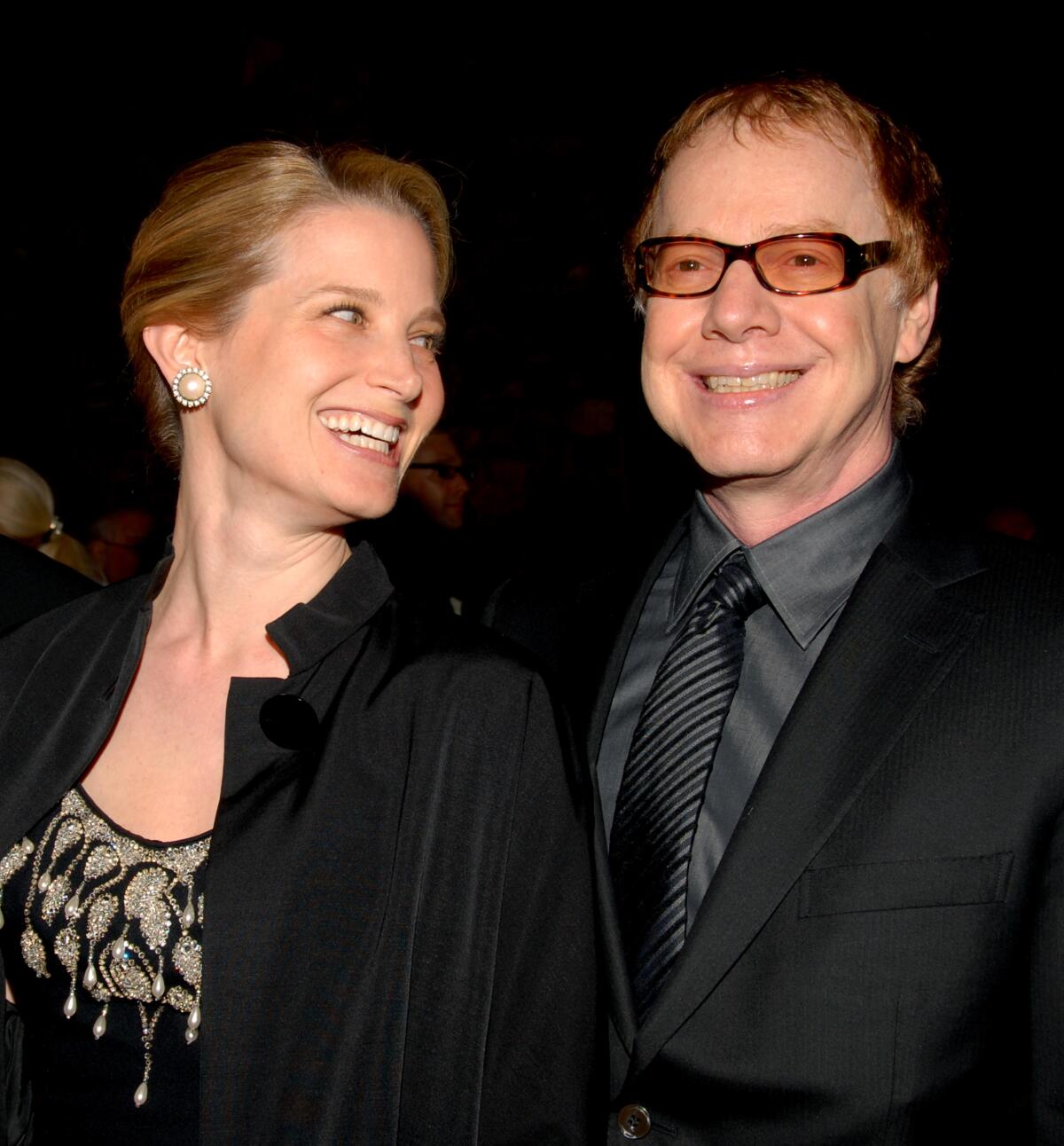

In fact, Elfman lives “somewhere north of Los Angeles” with his wife, actor Bridget Fonda, and their teenage son, Oliver. (The family recently sold their two homes in Hancock Park.) Elfman also has two adult daughters, Lola and Mali, from his marriage to Geri Eisenmenger.

Elfman grew up in Baldwin Hills, the son of a novelist mom and teacher dad. As a student at University High School in West Los Angeles, Elfman ran with the respected percussionist William Winant, West Coast new-music composer Michael Byron and former Sonic Youth bassist Kim Gordon. Elfman and Gordon dated, in fact.

“We were as different as night and day,” Elfman says, sitting on a comfortable couch in a room filled with drums the size of redwood stumps. “She was always cool — and I don’t mean ‘trying to be cool.’ The kind that you’re born with and other people try to imitate. I was the opposite — a hyperactive OCD geek.”

At 18, he and a friend booked a flight to Paris with the intention of heading south into Africa. While in France, they met up with Elfman’s older brother, Richard, who was performing in noted French theater director Jérôme Savary’s traveling Le Grand Magic Circus.

Obsessed with French Italian jazz violinist Stephane Grappelli, Danny had packed his violin for his transcontinental adventure. Upon arrival, Savary invited him and his friend to join the circus band as they traveled through Europe and Africa.

Elfman called his yearlong journey an exile from “middle-class white suburbia in the most extreme way ... like my DNA was being reprogrammed.” Any notion that Elfman might settle for a 9-to-5 job upon his return was rendered moot. He joined his brother’s Mystic Knights of the Oingo Boingo as musical director the day after he landed at LAX.

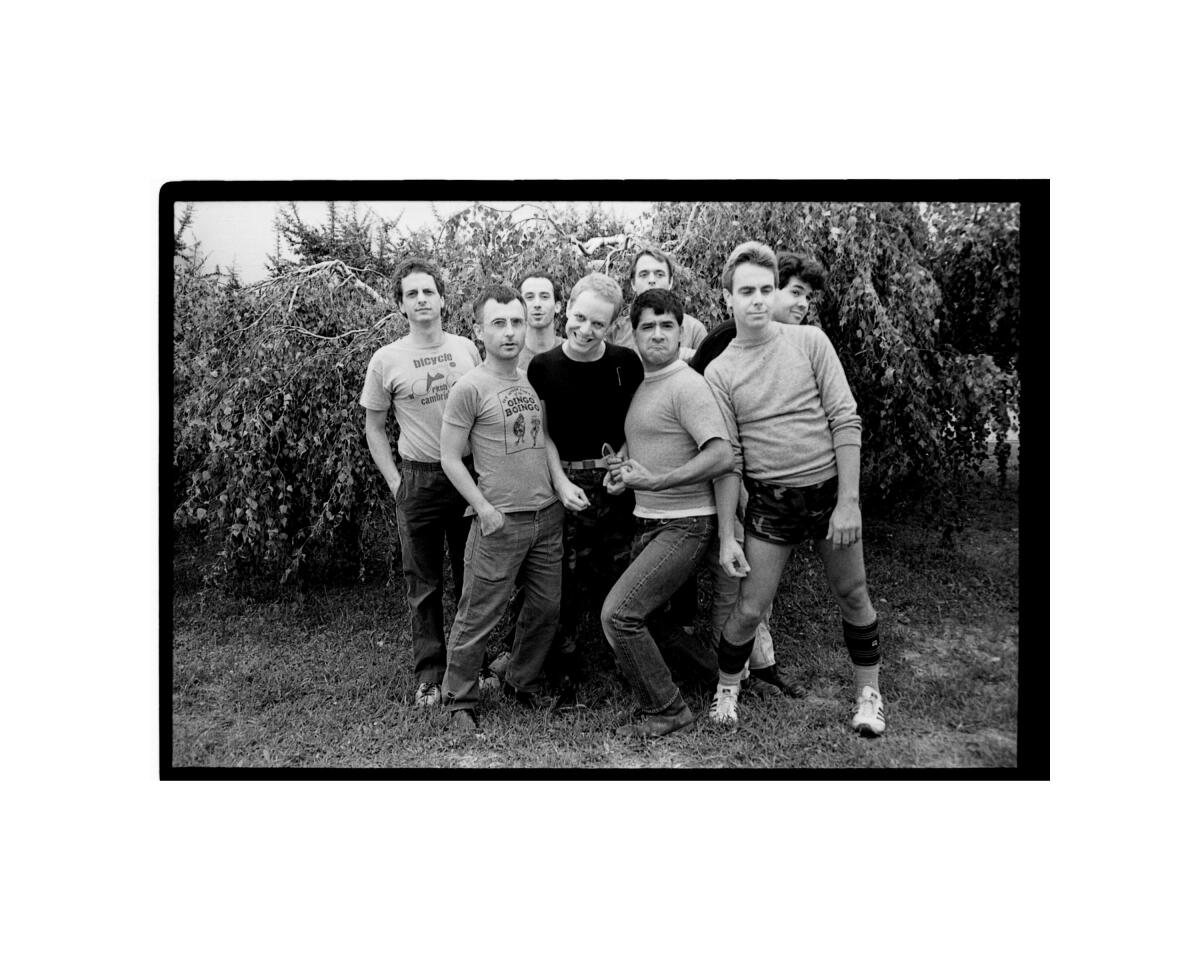

Established in 1979, Oingo Boingo, as they became known, mixed ska, punk, jazz and a Zappa-esque experimental streak during the rise of new wave. Elfman became Oingo Boingo’s leader after Richard left to produce and direct the 1980 cult classic “Forbidden Zone,” which starred Danny as Satan. “I never fit into anything in my life here,” Elfman says. “There was nothing I ever felt aligned to.” Oingo Boingo “might as well have come from Mars — this weird, surrealistic cabaret. Theater critics hated it. We used to print the worst reviews in our ads.”

Still, the band became a SoCal mainstay, releasing eight albums between 1981 and 1994 and earning attention for songs including “Little Girls,” “Dead Man’s Party” and “Weird Science.” That’s their “Goodbye Goodbye” playing over the closing credits of the 1982 teen classic “Fast Times at Ridgemont High.”

Burton first saw the band as a CalArts student at early punk clubs Madame Wong’s and the Whisky a Go Go. “I don’t know if it’s my background in animation but it seemed very filmic,” Burton recalled on the phone from England. “They had different instrumentation — more of a theatrical experience and a funny way of being a rock spectacle. Something about the rhythm sounded like weird animation music.”

At the height of Oingo Boingo’s popularity, Elfman entered the world of film scoring, collaborating with Burton on the director’s first feature film, “Pee-wee’s Big Adventure,” the now-classic 1985 movie starring Paul Reubens. “None of the old guard really accepted him,” Burton recalls, describing the tension as “a rite of passage, but it was a two-way street.”

Famously, Elfman fired legendary film composer and conductor Lionel Newman (of the famed family of L.A. film composers) after a “Beetlejuice” session in which a sarcastic Newman derisively called him “Beethoven” in front of the orchestra.

Elfman’s Oingo Boingo bandmate and longtime orchestrator Steve Bartek witnessed the Newman exchange from the control room. “Lionel thought it was his place to have an idea what the score should be like, and it was not Danny’s idea,” says Bartek. According to Bartek, they later learned that Newman had been telling the orchestra the opposite of what Elfman had instructed. “Danny is very adept at how to say what it is he wants,” observes Bartek.

That skill has continually drawn Elfman into Burton’s world, even if both have acknowledged creative tension in the past. Asked whether his and Elfman’s partnership has ever devolved into screaming, Burton replies dryly, “It’s more like psychological torture.”

Despite the torture, Burton keeps returning to his decades-long collaborator because his work wends its way into movies until it becomes an invisible character. Elfman’s scores also perform well, which Burton first witnessed during a pre-release “Beetlejuice” showing. Producers first screened the film without Elfman’s score. “It didn’t test that well,” says Burton. “Then when we put the score in, it was like adding a character — it was part of [the movie]. It was like missing an actor if you didn’t have it in there. That’s happened quite a bit.”

Elfman’s scores have gone on to propel hit films from Burton’s “Batman” to Gus Van Sant’s “Good Will Hunting” to Sam Raimi’s “Spider-Man.” He won an Emmy for his opening theme to “Desperate Housewives” and earns Screen Actors Guild money every time his theme song to “The Simpsons” drifts in with a trio of voices, one of them his, singing a three-note theme. And local Halloween celebrants have come to revere Elfman for his annual Hollywood Bowl performance of “The Nightmare Before Christmas,” backed by a full orchestra. (The live-to-film concert comes to Banc of California Stadium on Oct. 29.)

Elfman had begun preparing for a full-blown return to live music when the pandemic hit. Coachella promoter Paul Tollett, who had been unsuccessfully pushing for an Oingo Boingo reunion, flew Elfman to the festival via helicopter in 2019. That year, composer Hans Zimmer brought film scoring to the festival with a well-received set of his movie themes. But Elfman was more struck by Janelle Monáe’s show and the way she wed sound and visuals. He pitched a performance that was half film music and half band. Tollett agreed and Elfman enlisted Bartek and a band that included Nine Inch Nails’ Robin Finck and session drummer Josh Freese.

Liz Phair’s new album, ‘Soberish,’ reunites her with the producer of ‘Exile on Guyville,’ her influential indie-rock masterpiece.

Elfman and band spent three months producing and rehearsing for Coachella by revamping a half-dozen Oingo Boingo songs. “I looked where we are politically and I said, ‘Which of these old songs feel relevant today? Oh, my God, we were already talking about dystopian fascism and everything else.’” Elfman also dug into his popular TV and movie themes and composed a few new songs.

April 2020 was supposed to be a momentous month for Elfman. Not only was there Coachella but he was scheduled to begin rehearsals with the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain for the world premiere of an Elfman symphonic work. He’d booked dates for “The Nightmare Before Christmas,” and there was the premiere of a new percussion piece.

“I was hyped and ready to go,” Elfman says.

When COVID brought the curtain down on live music, Elfman fell into what he called “a deep funk.” Because of his anticipated concert schedule, he’d turned down all 2020 scoring projects. He was as idle as he’d ever been. “The first year that I’m finally taking no film music in order to commit to live performances — and it completely implodes.”

Despite the disappointment, he was still buzzing from the Coachella rehearsals and the way in which the band manifested his ideas, so he kept grinding away in his home studio.

“Big Mess” wasn’t finished when Elfman invited Epitaph Records owner and Bad Religion founder Brett Gurewitz to his studio. Gurewitz likened the meeting to “having a tour of Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory by Wonka himself. He showed me his collection of esoteric instruments and objects and eventually took me to a studio where we listened to highlights from the record.”

Gurewitz was awed by what he heard, telling Elfman that it reminded him of “a gothic ‘Sgt. Pepper.’” Gurewitz adds, “Danny doesn’t really have a rock background — he just sort of makes it up as it goes along. But he’s taking everything he’s learned on the scoring and orchestral side, and combining that with his innate goth-rock style.

“He’s uncompromising,” Gurewitz adds. “He has a vision. It’s a bizarre vision, and we just want to facilitate it.”

“He really should have done it a long time ago,” Bartek concludes.

Asked why he thought Elfman waited 30 years to release another solo album, Bartek replies with affection, “His agents kept him busy.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.