- Share via

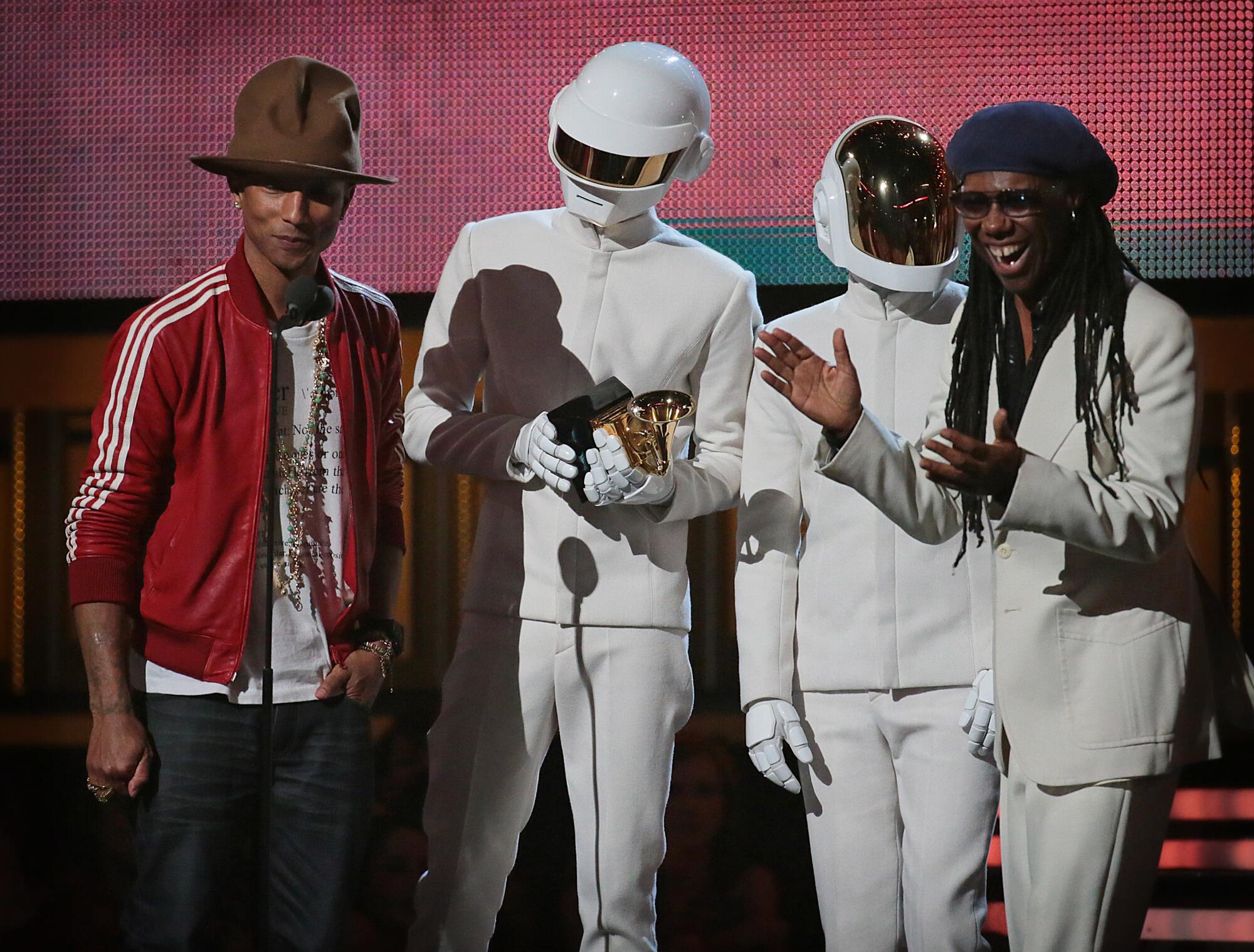

On the night of Jan. 26, 2014, Thomas Bangalter and Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo of Daft Punk leapt onto the stage at Staples Center to accept the Grammy for album of the year.

Even though the French electronic duo’s faces were hidden behind white and gold robot masks, they couldn’t hide their elation as they waved back to cheers from Jay-Z, Taylor Swift and Kendrick Lamar. Their album “Random Access Memories” and its smash single “Get Lucky” were crowning achievements in a career of immaculately produced dance music, played at pop-star scale.

Meanwhile, somewhere in the flatlands of L.A., far from the limos and gowns at Staples Center, Eddie Johns bedded down for the night.

Johns doesn’t remember exactly where in L.A. he was living back then, but it was almost certainly somewhere bleak. The Liberian-born singer, now 70, struggled with homelessness here for more than a decade; he had a stroke 10 years ago that left him unable to work and forced him onto the streets or into shelters.

Four decades earlier, he helped put Daft Punk on the path to those Grammys.

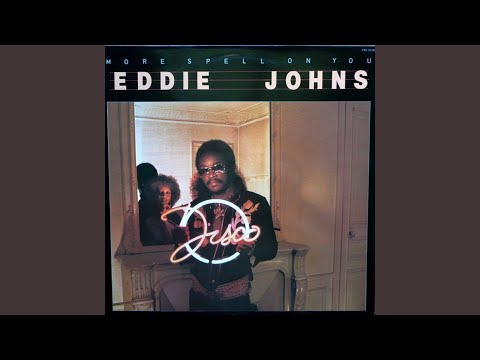

In 1979, when he was 28, Johns released an album, “More Spell on You,” with a punchy disco title track he recorded in Paris and released in Europe. Johns’ pleading lyrics about a desperate love — “I’m gonna put a spell on you, because that’s the only thing to do / So that you’ll never get away” — rode an uptempo, brassy production. It didn’t earn the singer much attention at the time. But when Daft Punk recorded its 2001 album “Discovery,” the duo found it and heard something they liked.

They chopped the track’s champagne-fizzy horn sections into short samples (a portion of a previously recorded song) and, as the band verifies, rearranged them into new hooks for the track “One More Time.” That song became Daft Punk’s biggest hit to date and its first million-selling single. It grew the duo from a respected club-music act into one of the most popular electronic groups on earth. Pitchfork called “One More Time” the fifth-best song of the 2000s, and Rolling Stone called “Discovery” one of the 500 best albums of all time, in any genre.

Johns says he hasn’t seen a dime from it.

Friends since the ‘90s, two of rock’s grandes dames gather to discuss Faithfull’s new album, “She Walks in Beauty,” and their near-death experiences in 2020.

“I help Eddie use the computer sometimes, and he showed me some of his music,” said Alyssa Cash, who since September has been Johns’ case manager at the supportive housing charity PATH. After Daft Punk announced its retirement in February, amid all the praise for their achievements, she wanted Johns’ part to be remembered too.

“He showed me his album cover, and when I found this video talking about how it was sampled by Daft Punk, it was like a lightbulb went off. ‘That’s Eddie, this is his song.’”

“I just hope I can get some credit, you know?” Johns told The Times (he is not listed as a songwriter on “One More Time”). He wants his family and the world to know that, whatever else happened to him, his music was important: “I’d like to have something to give to my daughter.”

A representative for Daft Punk confirmed that they have, for years, paid royalties to officially license the sample of Johns’ song. “‘One More Time’ contains extracts of the recording ‘More Spell on You.’” the representative said. “Daft Life LTD. is paying royalties twice a year to the producer and owner of ‘More Spell on You.’ … Per the agreement it is the duty of the producer of ‘More Spell on You’ to pay (part of such) semiannual payments to Eddie Johns.”

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

The rights to “More Spell on You” — first released in France on the label Président — were acquired by a French label and publishing company, GM Musipro, that reissues vintage French rock and pop. It’s where Daft Punk pays its royalties for permission to sample “More Spell.” The firm’s founder, Georges Mary, confirmed via phone and email that his company does receive those payments from Daft Punk but did not specify an amount.

“We have not heard from [Johns] since the day we acquired in 1995 a catalog from another label that featured this title,” Mary wrote. “We have tried to do research on him, but without any result. For our part, we are going to study his file and do the accounts to his credit. We will get back to him immediately on this subject, at the same time as we will inform him of his rights.

“We ask you in the meantime to convey our sympathy to him,” Mary added.

From Paris dance-floors to L.A. shelters

On the sun-cooked back patio of PATH’s complex in Pico-Union, Johns walks slowly, leaning into his cane. He’s still got a flash of his dapper disco days, behind dark sunglasses and a brightly striped tie. After his stroke, he talks very quietly but still with a cosmopolitan tang from his youth in West Africa and in France.

He lives alone in a one-bedroom apartment, with simple furniture stacked with books from PATH’s library. “It is very comfortable here,” Johns said, relieved to be somewhere stable.

Johns grew up with seven siblings in Liberia. His father worked as an accountant for an American company and his mother was a nurse. “She was always singing or humming while doing housework,” he said. He discovered he had a gift for singing, and fell in love with American rock and soul artists like Aretha Franklin, Johnnie Taylor, Jimi Hendrix and Eddie Floyd.

He moved to Paris in 1977 to make records, though he sometimes struggled to earn money, and experienced bouts of homelessness there. The first song he remembers professionally recording was a cover of Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’ “I Put a Spell on You,” which came out on Polydor in 1978. The French composer Gérard Salesses, who worked with Grace Jones, arranged it. “I recorded it in one breath,” Johns recalled. “I thought, ‘My mom is going to be so surprised.’ I just wanted to make her proud and maybe get her some money.”

With his new album, ‘Eduardo,’ 20-year-old Ed Maverick leads Mexico’s new generation of indie-rock romantics.

He played a few club gigs around Europe to support the record. Johns returned the next year with an album of covers and originals, including “More Spell on You.” It showcased Johns’ pleading, just-ragged-enough vocals, with distinctively keening horns that drew from American contemporaries like Chic and Sister Sledge.

Jean-Paul Missey, who recorded and mixed “More Spell on You,” was the house engineer at Paris’ Grande Armée studio at the time. He said he only distantly recalled Johns and his sessions but loved recording during the disco-fevered Paris of the era. “I rarely knew the time I’d go to sleep,” he said in an email. “It was a rewarding time for music and a great time for me.”

His favorite techniques helped define Johns’ sound: “Rhythmic bass, string accompaniments, brass and a chorus to finish the vocals,” as he put it. “It was a time when the soundman participated in the realization of an album,” which likely attracted the famously meticulous Daft Punk.

Four-on-the-floor rhythms were popular among rockers then, but West African acts like Fela Kuti and Manu Dibango had become international stars, and Johns saw a chance to make it big. But he admits he didn’t know how to navigate the record business. “I was so caught up in everything that I didn’t get legal protection,” he said.

He released another album, the suave and synth-inflected “Paris Métro,” in 1980. But as his music career stalled out, he didn’t quite know where to turn next. Like so many others, he came to California hoping for a fresh start.

“I liked ‘More Spell on You’ more”

You can go on YouTube and watch amateur producers slice up “More Spell on You” into a capable facsimile of “One More Time.” In real time, they cut, EQ and stutter-step the horns to re-create the song’s regal thump. Daft Punk and the American singer Romanthony wrote a new vocal melody on top of it, but the pieces from “More Spell” are the audio signature of the track.

Sampling is as old as hip-hop and forms the DNA of much dance music. In the 1970s, American soul and R&B bands upped their tempos into disco, and European producers twisted synthesizers into looping club music. DJs and producers playing Black and Latin gay clubs in Chicago and Detroit smashed both genres together to create house and techno. In the late ’90s, Daft Punk went back to those roots to dig for material.

Tim Lawrence, a dance-music historian and professor of cultural studies at the University of East London, said the late-’70s era of disco and funk “turned out to be arguably the richest for contemporary dance music producers, who regularly want to inject a level of instrumental skill or sonic distinctiveness in their electronic recordings.”

“Daft Punk tracks don’t sound like they were recorded during the ’70s,” he continued. “But Daft Punk has long been drawn to the organic warmth of analog sounds. They provide something that the precisely ordered 0s and 1s of digital recording culture can struggle to provide. They help new recordings cut across time.”

Daft Punk was, laudably, open about this process. The duo shouted out dozens of pioneers like Jeff Mills, Louis Vega, Joey Beltram and DJ Deeon on their 1997 single “Teachers.”

But one person they didn’t credit was Eddie Johns. Among the registered songwriters on “Discovery,” Daft Punk credit sampled material from George Duke (on “Digital Love”), Edwin Birdsong (on “Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger”) and Barry Manilow (on “Superheroes”), and each earns a portion of the revenue generated by those songs. But Johns’ name remains missing from the album’s credits.

“My daughter told me about Daft Punk,” Johns said of discovering “One More Time” after its release. “But I didn’t pay attention to what she said at the time because I was no longer in music. But one time, I was at the library in Pasadena, I was listening to a song from my album, and I found a video of engineers talking about how Daft Punk transformed ‘More Spell on You,’ how they were changing the sound.”

Did he like what they did with it? “Ehhh…,” Johns said, smiling. “I liked ‘More Spell on You’ more.”

In the first area concert since the pandemic, and the first at SoFi Stadium, Foo Fighters, Jennifer Lopez and Prince Harry appear at “Vax Live.”

“Discovery” was certified gold by the Recording Industry Assn. of America, meaning it sold at least 500,000 copies in the U.S., and it sold millions more across Europe. While payments from streaming services such as Spotify and Apple Music are divided among labels, artists, publishers and songwriters, at hundreds of millions of streams, and millions of physical and digital albums sold, even a piece of “One More Time” likely is worth something significant.

“It would depend on the division of income, but it is a substantial amount these services are paying,” said Erin Jacobson, a Beverly Hills attorney specializing in music industry intellectual property. She doesn’t work with the parties involved here but deals with similar cases.

“Generally, a song with that amount of streams would be earning in the high six- to seven-figure range on streams alone,” she estimated.

When a popular artist samples a more obscure artist, it can be difficult for the latter to get paid. Even for artists sampling in good faith and eager to pay, it can be hard to figure out who to cut the check to.

“Smaller artists are more vulnerable to infringements, but it’s a common problem that the rights owner can’t be found, or the record company has gone out of business, or it’s unclear who owns the rights,” Jacobson said. “It makes it more difficult for artists wanting to sample. Many artists will take the risk and use it, and just deal with it once somebody recognizes it.”

If fairly compensated, an appearance on a hit like “One More Time” can be life-changing. For an artist like Johns, who has suffered greatly on the streets of L.A., it could mean the difference between homelessness or safety.

Johns first came to America to be with his sister in New York, after his music career wound down before he’d hoped. He hated the cold and left for L.A. about 18 years ago. At first, he had his own apartment here and largely supported himself, but after his stroke, he found it impossible to keep working. He cycled through homeless shelters in Boyle Heights and Long Beach until he arrived at PATH’s Pico-Union complex in 2019.

He’d first come out west with his daughter in tow, but “I didn’t want to expose her to that life,” Johns said. “It was a very hard time. The shelter life broke me up.”

Johns’ wife picked his daughter up and returned her to France, where she still lives today. Johns said hasn’t seen his daughter in many years — “I try to reach her but she’s very busy,” he said, his eyes a little downcast.

He knows he’s lucky to have found housing in the midst of the city’s homelessness crisis. His life in L.A. is quiet but reliable, and he spends days reading favorite Bible passages and “writing songs now and then,” he said. It’s a huge improvement from the anxieties of being unsheltered.

“I’m blessed that I’m still here,” he said.

Johns’ situation comes at a gold-rush moment for music publishing. Streaming has buoyed the recorded music industry and made older songs more accessible to fans, and thus the projected value of songwriting copyrights has skyrocketed. Superstars Bob Dylan and Paul Simon recently sold the rights to their songs to publishing giants Universal Music Publishing Group and Sony Music Publishing, respectively, for hundreds of millions of dollars. Meanwhile, the U.K.-based Hipgnosis Songs Fund has led the pack of heretofore lesser-known companies spending billions to purchase the songwriting catalogs of everyone from the Red Hot Chili Peppers to Carole Bayer Sager.

For hip-hop and EDM in particular, sampling has long scrambled the idea of who owns a song. Initially, hip-hop artists used it to freely mine music history to create new tracks on a budget. But after Irish singer-songwriter Gilbert O’Sullivan sued rapper Biz Markie in 1991 for using a piece of his hit “Alone Again (Naturally),” the calculus changed in favor of the sampled act rather than the artist. Today, only well-financed artists can typically afford to sample prominent material.

Race, as always, complicates the ways artists lift or credit musical ideas. It’s a story as old as vaudeville and Elvis, up through Led Zeppelin, Vanilla Ice, Madonna’s “Vogue” and Diplo. European dance music is inseparable from the Black acts that white superstars often sample (like Avicii using Etta James’ vocals on “Le7els,” which kicked off the EDM boom of the 2010s).

“The question of musical ownership is a thorny one,” Lawrence said. “The process of researching and selecting samples is one that requires musical knowledge and skill. If the sample is paid for, then the musician is arguably both paying homage as well as royalty fees. But when a privileged artist uses material from another artist, it’s only right that that material should be paid for.”

Jacobson agreed: “Creators’ rights have to be respected, and everybody should share in that income,” she said. “Especially in a situation where the music is already being used.”

But determining what, exactly, Johns is owed two decades later will be complicated.

When an artist samples a record, they need permission from the owners of the master recording (usually a record label) and the owners of the songwriting (usually the writer or their publishing company). Sampling licenses are negotiated individually, and fees vary widely.

The song “More Spell on You” is registered with France’s publishing agency SACEM, which administers royalty payments for songwriters. Johns is listed as “More Spell’s” main writer and performer, while Salesses is listed as a composer. (SACEM did not return requests for comment.)

Income from “One More Time” would be subdivided between the various labels, publishing companies and the artists, depending on their agreements. “What part of that Eddie shares in, we don’t know yet,” Jacobson said. “But it does seem that Eddie should have some credit on the composition and the master side, which didn’t get handled. Now it’s up to all the parties to remedy that.”

Missey, Johns’ mix engineer, hopes Johns finally sees his share of the record they made. “I think that the profit from it should also benefit the first creators, who took the initial risks,” he said.

Daft Punk retired after a career of sold-out stadiums and Grammy-winning albums. Johns never expected anything close to that for himself. He just wants what he was always looking for in music — whatever bit of money he’s due, and the respect he sought for his work back then.

“I did always wonder if the song was a success or not,” he said. “I went on with my life in another direction. But I wish I had gotten paid. I would have been in a better state of mind. My mother would have been very happy. I always just wanted to impress her.”

Anousha Sakoui contributed additional reporting to this story.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.