How Bad Bunny broke every rule of Latin pop — and became its biggest and brightest star

- Share via

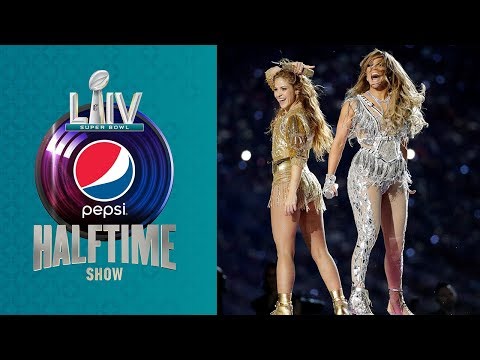

CHICAGO — Bad Bunny had just finished performing with Shakira at the Super Bowl halftime show and was being rushed back to his dressing room when he stopped.

“Listen, we’re going to stay here,” he told his handlers. “The show’s not over yet.”

For the next few minutes, as the crowd of 65,000 screamed for Jennifer Lopez and fireworks streaked the Miami sky, the 25-year-old Puerto Rican rapper lingered on the field. He danced with friends, posed for photos in his glittering, Swarovski-encrusted suit and took a moment — just a moment — to revel in the fact that in a handful of years, he had gone from bagging groceries at a supermarket to all of this.

“It was overwhelming,” he recalls. “And I said to myself then: ‘I have to slow down and enjoy things more.’”

It can be tough finding time to take stock of your life when you’re one of the fastest-rising stars in music.

In just a few years, Bad Bunny has remade reggaeton with his inclusive politics, freaky fashion and moody trap beats, challenging the genre’s deeply rooted stylistic and social norms while becoming one of the most streamed artists on earth.

At the same time, he has blazed new paths in the broader American market, churning out chart-topping hits with the likes of Cardi B and Drake and playing the country’s biggest arenas, all without the backing of a major label and all while rapping almost exclusively in Spanish.

Amid the collapse of traditional music genres and soaring global demand for urbano — an umbrella term that includes reggaeton, Latin trap, dancehall and dembow — everybody wants a piece of Bad Bunny.

And that is why, rather than taking a six-month break in sunny Puerto Rico that he had planned after two years of nonstop touring, he is here, shivering in Chicago, where he is taking part in the annual NBA All-Star Weekend. Bad Bunny loves basketball — a tribute song he wrote when Kobe Bryant died became an unexpected hit — and he couldn’t say no when he was invited to play in the celebrity game and rub shoulders with his favorite players.

But damn, it’s freezing out, and he is not prepared.

“I have never been this cold,” he declares in Spanish as he dodges from his hotel into the back of an SUV that will whisk him to the game. It is 9 degrees out and much of Lake Michigan is frozen solid, yet he is dressed in a sweatshirt with no coat. On the front of his shirt is a skull made of crystals. On the back are the letters YHLQMDLG.

That stands for “Yo Hago Lo Que Me Da La Gana” — the title of his new record, out Friday, and a phrase that is his mantra in life. Translation: I do what I want.

Before an awards show in 2017, he decided on a whim to paint his fingernails, a small act that set off shock waves in reggaeton’s machista culture even as young men around the globe began copying his style. “He’s just very different,” said Fernando Lugo, who has directed nearly 30 music videos for the star. “He’s kind of magic.”

Yet on this afternoon, as we cruise down Lake Shore Drive, Bad Bunny is feeling uncharacteristically anxious. He knows he’ll soon be facing questions — in English — from a pack of journalists.

In the past he would have answered them in Spanish, but he has lately been cramming with an English tutor up to eight hours a day. His assignment this afternoon: Flex his new language skills.

“I’m nerrrvous,” he says, looking up from scrolling on Instagram to emit a comical groan.

His publicist tells him not to worry, that the media will meet him on his own terms, just as everybody else has in his career so far.

“Remember, Benito,” she says, using his given name. “You’re not crossing over to them; they’re crossing over to you.”

Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio grew up in Vega Baja, a town about an hour from San Juan, the oldest son of a truck driver (his father) and a teacher (his mother). He always tried to stand out, wearing above-the-knee shorts favored by skaters and flashy patterned shirts, a kind of preppy swag look distinct from the baggier hip-hop garb popular at the time.

“My dad would say, ‘You’re really going out like that?’” he recalls. “But he always supported me.”

Growing up, Benito soaked up the sounds of iconic reggaeton rappers such as Daddy Yankee and Vico C as well as the Juan Gabriel and Héctor Lavoe that his mom blasted while they did housework. He still loves listening to salsa.

In 2016, he was working at an Econo grocery store and paying his way through college when he started uploading songs to SoundCloud. He was one of a handful of musicians on the island experimenting with trap rhythms.

Noah Assad, a music lover who had been booking acts since he was a teenager, stopped in his tracks when he first heard “Diles,” on which Bad Bunny sings about sex in a deep, slurry baritone over a hard Atlanta beat. It felt, Assad said, like a Gen Z reinvention of reggaeton, which had emerged from the island’s poor barrios in the 1990s.

He was intrigued, too, by Bad Bunny’s irreverent moniker, which stood out in an industry with serious egos. “I wanted to meet this guy just because of the name alone,” Assad says.

He became Bad Bunny’s manager, and they began releasing dozens of dozens of singles in quick succession, always with a video attached. They never concocted an elaborate crossover strategy. Instead, they just flooded the internet with content and watched as demand grew.

In 2018, Assad eventually put out Bad Bunny’s critically acclaimed debut album, “X 100pre,” on his own indie imprint, Rimas Entertainment.

There had never been an urbano album like it. With the help of producer Tainy and with assists from Diplo and Dominican dembow legend El Alfa, Bad Bunny wove together an experimental soundscape of trap, reggaeton, bachata and even synthpop, and added a certain sadboi lyricism that drew easy comparisons to Drake (the stars collaborated on a song on the album, “Mia,” whose video has been viewed nearly 1 billion times on YouTube).

Last year, he released “Oasis,” an eight-song EP with Colombian rapper J Balvin that dabbled in rock and Afrobeat. It too was a smash, earning the pair a Grammy nomination for Latin rock, urban or alternative album.

Bad Bunny’s new album, set for release on Feb. 29, has a different vibe altogether; it’s a party record packed with twerkable perreo hits. “I changed it all up,” he says of the album, which he recorded at a rented house in Miami in a closet converted into a vocal booth. “When people expect something from me, I like to go in the other direction.”

That ethos applies to his politics. Last year he led protests in Puerto Rico calling on the island’s governor to resign — and his attitudes toward gender and sexuality. On social media, he has sung the praises of women who don’t shave their body hair, criticized a Spanish nail salon that barred him entry and called out reggaeton star Don Omar for making anti-gay comments.

“Homophobia in this day and age?” Bad Bunny tweeted. “How embarrassing, man.”

Sure, his music videos feature their fair share of bikini-clad female models and, sure, he sometimes raps about stealing your girlfriend. But he has also written songs about domestic violence (“I’m not yours or anyone’s / I am mine alone,” he sings on “Solo de Mi”), and his videos often feature long-excluded faces, including same-sex couples, transgender women and people with disabilities.

“There are people who listen to reggaeton and love it and at the same time they have never felt represented within it,” he says. “In 20 or 30 years nobody had worried about that, but I did.”

As for questions about his own sexuality, he’s not particularly interested in them. Like a lot of people of his generation, he views sexuality as fluid.

“It does not define me,” he says. “At the end of the day, I don’t know if in 20 years I will like a man. One never knows in life. But at the moment I am heterosexual and I like women.” He says he is seeing somebody now, though he declined to name the person.

Back on the All-Star red carpet, it turns out that Bad Bunny and his English tutor had nothing to worry about. He kills it, slapping journalists on the back as he talks with them about the frigid weather and about his favorite NBA players (Bryant, of course, but also LeBron James, whom he brought onstage for a bear hug at Calibash in Las Vegas in January).

His performance on the court, though, was less impressive. He spent much of the game glued to the bench, but he did score one basket — “my bucket” he proudly says later in English — and he looked extremely cute in his baby pink jersey (he asked to be on the pink team, of course).

When the MVP trophy was presented at the end of the game, Bad Bunny jokingly approached the podium to claim it — a gag that quickly becomes an Internet meme but seemed more designed to humor his friends and younger brother, Bernie, in the stands.

He travels with a tight-knit entourage of young men who have known him long before he was famous: arty kids who would generally rather smoke weed, listen to Travis Scott and dye their hair new shades of neon than go to celebrity-studded events.

During All-Star weekend, they skipped parties thrown by DJ Khaled and Megan Thee Stallion. Bad Bunny tucked into bed early, except for one night when he stayed up until 4 a.m. recording a song with fellow Puerto Rican rapper Myke Towers.

“People think we’re living the life,” says his friend Jesus Hernandez. “They think we’re going to after-parties, going to strip clubs. That almost never happens.” He sounds only a little bit disappointed.

After the game, the group heads to a deep-dish chain restaurant called Giordano’s. Bad Bunny has been on a diet for a few months, shedding weight he gained while touring, and has been saving up his cheat meals for two days. As soon as the pizza arrives, he takes a cheesy slice, flicks off the mushrooms and stuffs it in his mouth. He closes his eyes and groans with pleasure, uttering an unprintable bit of Puerto Rican slang that refers to a woman’s vagina.

The young waitress has no idea who he is.

“Where are you guys visiting from?” she asks, intrigued by the crew’s special-edition sneakers and Balenciaga sweaters.

“Puerto Rico!” Bernie pipes up.

Back home, Bad Bunny is so famous he can barely leave his house. The island loves its native son, whose success has been a rare bright spot during a tough period that has seen two hurricanes and an earthquake.

Last summer, he was on a boat in Ibiza, taking a break during a European tour, when protests began erupting in San Juan about leaked messages from Gov. Ricardo Rosselló that hinted at corruption.

In videos on Instagram, Bad Bunny fought back tears as he denounced what he described as the island’s history of mismanagement.

“You have to go to the streets,” he urged his fans, before canceling several concerts to lead them himself. Shortly after he, Ricky Martin and his friend Residente helped shut down a major highway in protest, Rosselló announced he was resigning.

He feels the urge to go back to the island, to dig his toes into the sand. But there are so many opportunities calling. He’s busy, yes, but he’s happy.

After All-Star weekend had ended and the Chicago snow had turned to a cold rain, he and his friends were preparing to film a music video. As they chose their outfits, they listened to salsa.

“I don’t think I’ve ever felt as good as I do right now,” he says, flashing a smile. “The plan right now is just to enjoy everything.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.