Welcome to the ‘Hotel California’ review: In Vegas, the Eagles perform their definitive album

- Share via

LAS VEGAS — Since 1976, the Eagles have sold more than 26 million copies of their fifth album, “Hotel California.” It’s the third-biggest-selling album in American history, beating out everything but Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” and “Their Greatest Hits 1971-1975,” also by the Eagles.

Back when people owned CDs, even people who owned fewer than 20 seemed to own a copy of “Hotel California.” The title song remains supremely ubiquitous — it’s unavoidable on classic-rock radio, but also in pop culture, from “The Big Lebowski” to Frank Ocean’s first mixtape. It’s playing in Tony Soprano’s basement in “The Sopranos” episode where Tony and Carmela bicker about the elliptical machine while the FBI listens in; it was playing in my local 7-Eleven the day before I drove to the MGM Grand in Las Vegas to watch the Eagles perform the “Hotel California” album live in its entirety for the second time ever. (The first time ever was the previous night.)

Of course, in the mythos of the Eagles, “Hotel California” doesn’t just represent a commercial pinnacle — it was also the beginning of the end. The Eagles’ cocky, jock-y perfectionism instantly set them apart from the mellow folk-rock scene that spawned them, but at the “Hotel California” sessions that creative ruthlessness began to set them apart from one another. In Alison Ellwood’s epic 2013 documentary “History of the Eagles,” Eagles co-founder Don Henley explains that Don Felder was replaced (by Don Henley) as vocalist on “Victim of Love” because Felder’s take “simply did not come up to band standards.” They would accept nothing less than a masterpiece, which is usually how bands run themselves into the ground.

The crazy part is that it worked. From the title track — a 6 1/2-minute flamenco-reggae ballad with an evocative, inscrutable lyric that may be about Satan or Steely Dan, depending which conspiracy theorist you ask — to the elegiac closer “The Last Resort,” it’s a consummately performed album that spun gold from surprisingly bleak themes: disillusionment and loss, the end of the ’60s, the splintering of the country itself. As the late Glenn Frey’s smuggler character Jimmy once said to Crockett and Tubbs on “Miami Vice,” “I always like to take a goodbye look at America, just in case it’s my last.”

The band wasn’t finished, but their innocence was. They’d make one more studio LP, 1979’s three-tortured-years-in-the-making “The Long Run,” the one where they finally stopped mourning paradise and became cynical citizens of the fallen world that replaced it, scoffing jadedly at golden-calf cultists from their bar stools at Dan Tana’s. “Hotel California” is that goodbye look, and they know it, and that sadness suffuses every song, even the one Frey wrote about riding shotgun in his drug dealer’s car. It’s the sound of guys who had everything coming to terms with the knowledge that everything must go.

Is Las Vegas, that monument to escapism, a somewhat counterintuitive place to restage “Hotel California’s” confrontations with the inescapable? Well, sure. But it’s also a perfect place to revisit an album about malevolent desert oases, American magic and dread, and houses that always win. Besides, isn’t “What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas” just another way of saying “What a nice surprise / Bring your alibis”? (“We are all just prisoners here of our own device,” while also accurate, wouldn’t do as much for the tourist trade.)

Backstage before the show, when asked what it meant to revisit songs like these in a place like this, Henley answered desert-dryly: “I’m well aware of the ironies.” Those ironies were occasionally unavoidable: A wide selection of T-shirts commemorating an album about the death of the hippie dream at the hands of cruel commerce could be had for $45 at the Eagles-merch pop-up by the venue’s entrance.

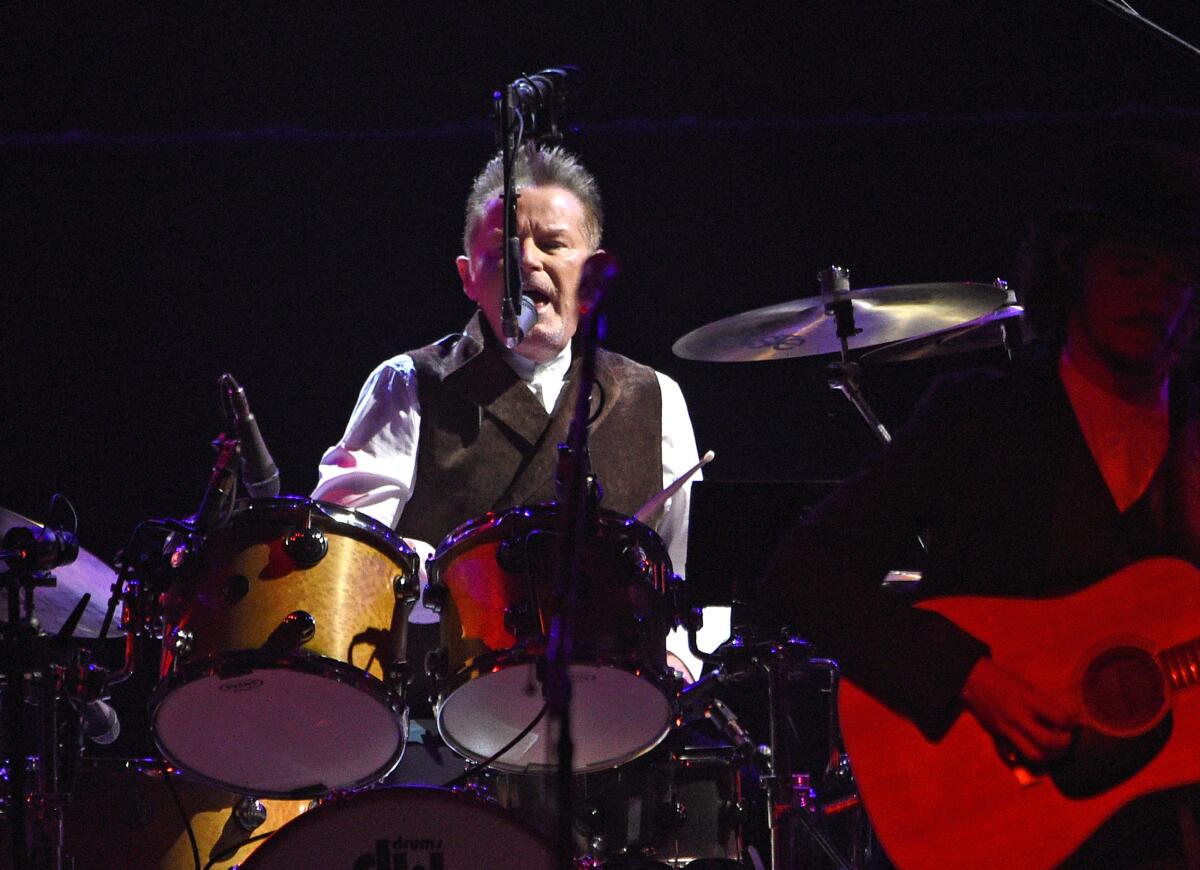

But the minute the lights went down on Saturday in the MGM’s packed Garden Arena, cognitive dissonance didn’t stand a chance. A towering, grim-faced actor in a black cape emerged from the wings to drop the needle on side one of a vinyl copy of “Hotel California”; this almost Lynchian act of summoning brought forth the Eagles, dressed in black and white like pallbearers at a hipster funeral or the Dalton Gang on their way to rob the Oscars. The newest Eagles wore the coolest hats — a gambler’s top hat for country legend Vince Gill, a natty bowler for Deacon Frey. Drummer/vocalist Henley sported a sea-captainish double-breasted vest and a high-and-tight haircut, worlds away from the ’fro he once rocked behind the kit.

Without a word of introduction, guitarists Joe Walsh (in boots and tails) and Steuart Smith — the unassuming virtuoso who’s held down Don Felder’s lead-guitar parts since Felder was fired in a bitter 2001 contract dispute — launched straight into “Hotel California’s” glimmering-mirage opening. It sounded like “Hotel California” always does, which was probably prudent; nobody comes to a Vegas revival of an uber-classic-rock record to hear its makers tinker with the original recipe.

But the other thing about “Hotel California” is that it’s a profoundly world-weary album about time’s inexorable passage made by guys who were barely 30. They’d each put themselves through 10 lifetimes’ worth of backstage debauchery by that point, but technically they were still young. The hard truths in the words to these songs hit differently when voiced by men in their 70s, to a room full of similarly-seasoned fans.

“Wasted Time” — the first song of the night to feature a 46-piece string orchestra conducted by Jim Ed Norman, who played in Henley’s pre-Eagles band Shiloh a lifetime ago — took on a rueful new weight, becoming an ode to the bittersweet corners middle age paints us into. And while Joe Walsh has always brought a tenderness to the ballad “Pretty Maids All in a Row” that belied his rep as the band’s hotel-trashing holy fool, hearing him sing “Why must we give up our hearts to the past / Why must we grow up so fast” in a voice audibly worn by consequence provided an unexpected moment of pathos.

In the second half of “History of the Eagles,” Jackson Browne recalls watching one of the band’s first reunion gigs with a euphoric Jack Nicholson, who turned to Browne and summed up the secret of the band’s enduring appeal in a single word: “Repertoire.” When the band briefly vacated the MGM stage after “Last Resort,” Henley promised they’d be back to play everything else they knew, and when they reemerged 20-odd minutes later, dressed further down, they delivered a two-hour-plus greatest-hits set that came close.

Aside from “Love Will Keep Us Alive,” a showcase for the still-angelic pipes of bassist Timothy B. Schmit, they mostly left the “Hell Freezes Over” era alone — hopefully the deep-cut enthusiast who hollered a request for “Get Over It” had better luck at the blackjack table. There was just too much other stuff to cover — a slew of Eagles hits, plus dips into both Henley’s solo catalog (a brisk “Boys of Summer”) and Walsh’s (“Walk Away” and “Funk #49,” all-timers by his old band, the James Gang).

Hours later, when they finally brought the pre-encore portion of the evening in for a landing with “Heartache Tonight,” the audience-cam briefly paused on a young man with a feathery shag haircut and the beginnings of a wispy mustache. He looked stoked, then spotted himself above the Eagles on a giant screen and looked even more stoked. As long as 1976 lives in the hearts (and on the upper lips) of guys like that guy, the world will always need an Eagles. They get older, and he stays the same age.

It’s still a band working around the absence of a key member — founding Eagle Frey, who died almost four years ago at 67 — and sometimes the amount of firepower on display felt compensatory. “Seven Bridges Road” featured six-part harmony and five different Eagles on acoustic guitar. But watching new Eagles Vince Gill and Frey’s son, Deacon, divide up what were once Glenn’s songs yielded some genuinely affecting moments as well.

Gill has sold more than 26 million albums since his country-hunk breakthrough in the ’80s, but he still looks bashfully stoked every time he receives the applause customarily afforded an Eagle. Deacon, meanwhile, looks a lot like his dad and more than a little bit like a dude who might buy your mountain bike on Craigslist. He’s not a born frontman; his stage presence is mostly symbolic.

It helps to know the back story: On Saturday night, when Deacon took the solo on “Try to Love Again,” he was playing Old Black, a Les Paul Junior with one broken pickup, supposedly gifted to Glenn by Jackson Browne, who got it from Jeff Hanna of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. The younger Frey handles this history the only way a sensible man could. He stands up there in a Colt 45 T-shirt — the beer, not the gun — and tries to ignore it. He doesn’t sing his father’s songs quite like his father did, but anyone attempting “Take It Easy” and “Peaceful Easy Feeling” at an Eagles show can always count on the help of a few thousand backup singers.

By sheer force of personality, the second half of the show belonged to Joe Walsh, who’s been lighting a fire under this band since 1975, give or take a few decades of downtime. A guitar genius, hall-of-fame goofball and enthusiastic maker of fast-lane life choices, Walsh is likely still breathing today because Felder and Eagles manager Irving Azoff drove him to rehab to ensure his fitness for the Hell Freezes Over tour; getting the band back together was worth it for that result alone.

On Saturday he was a show unto himself, contorting his face like a man fumbling for ecstasy and his locker combination at the same time, strafing “In the City” with swampy wah-wah effects and riding the talk-box solo on “Those Shoes” straight into psychedelic space. He also told the crowd to watch JoeWalshForPresident.com for an important announcement in about a week, avowing — to presumably bipartisan cheers — that he’d “had it.”

In 2012, Walsh backed Illinois Democrat Tammy Duckworth in her successful House race against a Republican, whose name was also Joe Walsh. That Joe Walsh has announced plans to mount a primary challenge to Donald Trump, which means there’s a slim but tantalizing chance that the 2020 election will pit the Joe Walsh who once supported building an alligator moat at the Mexican border against the Joe Walsh who made a solo album called “Got Any Gum?”

When Walsh last ran for the country’s highest office, he did so on a “Free Gas for Everyone” platform and a promise to make “Life’s Been Good” the new national anthem. In Vegas he offered no campaign promises, only an irresistible slogan: “Sleep well, America. Joe Walsh is awake.” Long may he stay that way.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.