Forget ‘snubs.’ The real winner in this year’s Oscar nominations is international cinema

- Share via

February is well upon us, and it wouldn’t take a groundhog sighting on Hollywood Boulevard to know that the interminable rituals of Academy Awards season will grind on for another several weeks. We have entered what I have come to think of as the Oscars’ interregnum, that anxious, frequently tedious period between the announcement of the nominees and the unveiling of the winners. During this period, which Judi Dench described in her own 1999 acceptance speech as the best part of the Academy Awards (“You live in a kind of haze for several weeks, and the terrible thing is that somebody’s got to win”), the movie industry primps, preens and prepares itself for battle. On Sunday, March 10, all will converge at the Dolby Theatre, surrounded by paparazzi battalions on a carpet fittingly dyed the color of blood: It’s Oscar night, baby, and all’s fair in self-love and war.

For now, though, a mild if suspicious calm seems to have descended on Hollywood, disrupted every so often by a fresh renewal of controversy around what too many ostensible journalists have called “the ‘Barbie’ snubs.” May I propose that, in the context of awards season, the word “snub” be banned, or at least looked up in dictionaries more often? Whether you think Greta Gerwig deserved to be nominated for director or Margot Robbie for lead actress, it takes a ludicrous suspension of disbelief to assume that academy voters deliberately and maliciously conspired to deny them. (Especially since they both received nominations in other major categories: Gerwig and her co-writer, Noah Baumbach, are up for adapted screenplay, while Robbie and her three fellow “Barbie” producers are nominated for best picture.)

The 2024 Oscar nominations were announced Tuesday, with big numbers for “Oppenheimer,” “Barbie” and two foreign titles, “Anatomy of a Fall” and “The Zone of Interest.”

The “Barbie” uproar became so intense, with Ryan Gosling, Robert Downey Jr. and even a former U.S. presidential candidate coming to Gerwig and Robbie’s defense, that at a certain point Robbie herself felt moved to push back gently against the “snub” narrative. Perhaps she and others sensed a looming backlash to the backlash, and rightly so: The notion that a billion-dollar blockbuster with eight Oscar nominations has been in any way slighted by the industry is ludicrous on its face.

I wasn’t surprised that Robbie’s wonderful performance — a subtler, trickier, less attention-grabbing one than Gosling’s — ultimately failed to place in a lead acting race that often undervalues comic performances, Emma Stone’s hilarious “Poor Things” shenanigans notwithstanding. I was even less surprised that Gerwig didn’t get a directing nomination, for reasons that have nothing to do with the quality of her work in “Barbie,” which is characteristically nimble and dazzlingly imaginative, than with her intense competition in a category that, unlike the 10-nominee best picture race, offers only five slots.

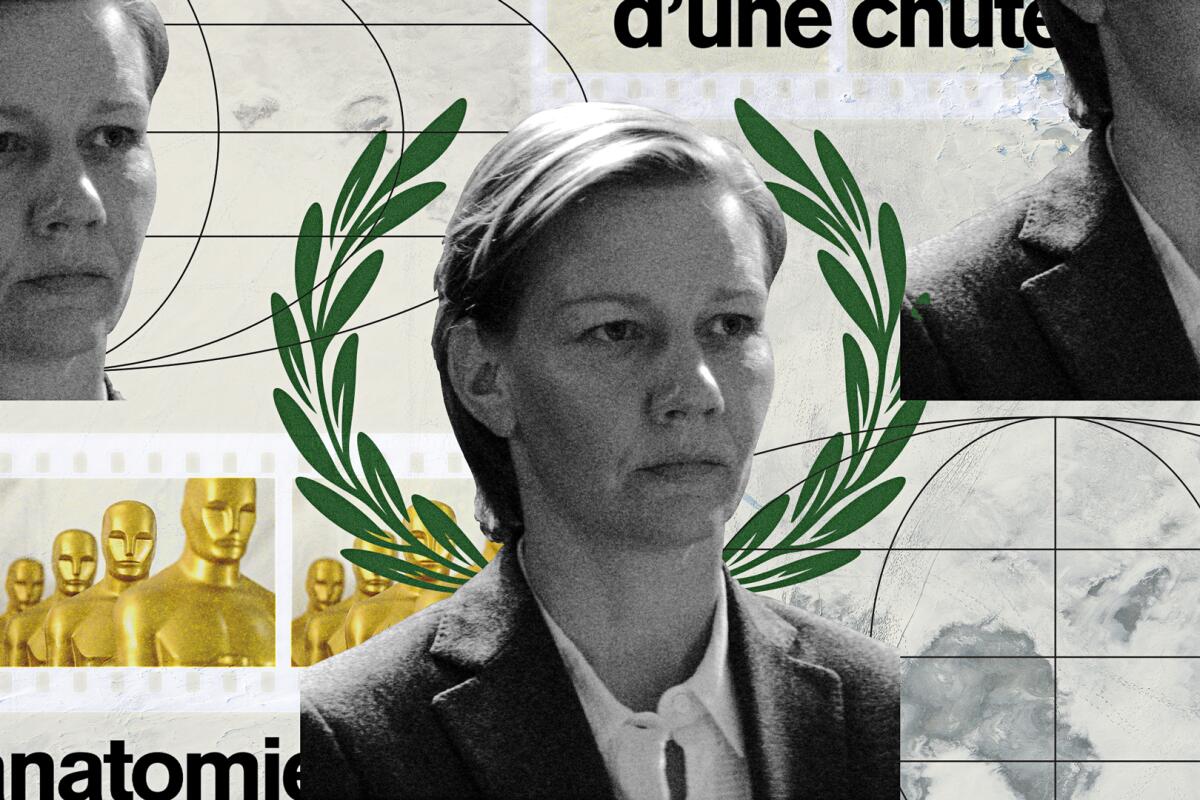

This year, those slots went to Jonathan Glazer (“The Zone of Interest”), Yorgos Lanthimos (“Poor Things”), Christopher Nolan (“Oppenheimer”), Martin Scorsese (“Killers of the Flower Moon”) and Justine Triet (“Anatomy of a Fall”). That’s as unassailable a lineup as any the directors branch has produced in recent years, and it’s interesting for several reasons. One is that while many were expecting Gerwig to be the category’s lone female nominee, that dubious honor went instead to Triet, who I’d suspected would crack this category for her roundly admired Palme d’Or winner, “Anatomy of a Fall.” (It received five nominations total, including best picture, lead actress for Sandra Hüller, adapted screenplay and film editing.)

It’s meaningful that the directors branch nominated Triet, a Frenchwoman whose work has seldom been screened in the U.S. until now. It would be even more meaningful, of course, if Triet weren’t the only woman director nominated, especially in a year that gave us not only Gerwig’s “Barbie” but Kelly Reichardt’s “Showing Up,” A.V. Rockwell’s “A Thousand and One,” Raven Jackson’s “All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt” and Celine Song’s best picture-nominated “Past Lives.” Triet’s nomination hardly refutes the contention that the predominantly male directors branch still has a serious sexism problem. And it’s easy to see how a bright, cheeky mainstream crowd-pleaser like “Barbie” might have had built-in biases to overcome that a self-evidently serious-minded drama like “Anatomy of a Fall” clearly didn’t.

At the same time, “Anatomy of a Fall” had its own significant hurdles: Let’s not overlook how rare and remarkable it is for a mostly French-language art-house drama to muscle its way into an Oscar race dominated by American blockbusters and prestige productions. That it managed to do so is testament to the growing diversity and discernment of the voting membership, and a reminder that said membership, thanks to nearly a decade’s worth of concerted reforms on the academy’s part, is more broad-based and international-minded than ever.

So are the “Barbie” omissions — OK, fine, “snubs,” if you must — a sign of gender bias or genre bias? A little of both, yes, and maybe something else: Call it global bias. I have to wonder if “Barbie” might be a victim less of sexism than of its own Amerocentrism, which may have cost it some resonance with academy voters abroad. (Writing about “Barbie” last year in a post on Twitter/X, the critic Guy Lodge asked, “Why no sense of Barbie as a global brand?” — a smart question that I haven’t heard a single American articulate.) Seen in this light, there’s something curiously blinkered in retrospect about the American media’s rush to anoint “Barbie” the Great Feminist Movie of 2023, a designation that overlooks, among other things, the darker, more complicated understanding of womanhood at the heart of “Anatomy of a Fall.”

I truly don’t mean to fall into the politically regressive trap of pitting one movie (or one woman) against another when I point out that the great feminist movie monologue of 2023, for me, was in Triet’s movie. I’m speaking of the flashback sequence in which the protagonist, Sandra (the galvanizing Hüller), refuses to apologize for her artistic success, her bisexuality, her tough-love parenting or her language preference for the sake of her husband’s ego. Sandra doesn’t utter the word “woman” once, and she doesn’t have to; the unfairness of her treatment and the cruelty of her husband’s entitlement reverberate in every frame.

I imagine more than a few voters had that sequence in mind when they cast their votes for Hüller, and also for Triet and co-writer Arthur Harari’s “Anatomy of a Fall” script. The unerring skill with which Triet brought all the elements of her filmmaking together clearly made her a formidable threat all along; anyone who expressed shock or surprise at her directing nomination clearly hadn’t been paying attention. They also probably haven’t noticed that the directors have been, by no small measure, the most international-minded branch of the academy for decades. Veteran Oscar watchers will remember the quadrumvirate of directing nominations for Federico Fellini in the 1960s and ’70s (for “La Dolce Vita,” “8½,” “Fellini Satyricon” and “Amarcord”).

They may also recall the years when world-cinema luminaries like Hiroshi Teshigahara (“Woman in the Dunes”), Michelangelo Antonioni (“Blow-Up”), Claude Lelouch (“A Man and a Woman”), Jan Troell (“The Emigrants”), Ingmar Bergman (“Cries and Whispers”), François Truffaut (“Day for Night”), Lina Wertmüller (“Seven Beauties”) and Akira Kurosawa (“Ran”) cracked the lineup. None of these filmmakers won, sadly, but it means something that they were invited to the ball. And it’s long-standing evidence that directors, more than any other branch of the academy, see the medium of cinema as its own lingua franca and recognize when a great filmmaker from outside the U.S. wields that language with particular brilliance.

Which brings us to the other interesting thing about this year’s category: Scorsese is, remarkably, the only American-born director in the race. Lanthimos is Greek, Triet is French and Glazer and Nolan (the widely projected winner) are both English. Two of them, Glazer and Triet, were nominated for art-house dramas that were scripted and shot in languages other than English; “The Zone of Interest” is in Polish, German and Yiddish, and “Anatomy of a Fall,” while it features a good smattering of English, is predominantly in French. For some of us, too, the multiple major nominations for “Anatomy” and “Zone” marked the near-culmination of a journey that began at last year’s Cannes Film Festival, where they nabbed the top two prizes.

The impact of Cannes on the Academy Awards has ebbed and flowed over the years, but in recent years its influence has become hard to ignore. Of all the European and Asian directors who have received Oscar nominations over the past decade or more, nearly all of them — Michael Haneke (“Amour”), Pawel Pawlikowski (“Cold War”), Ryûsuke Hamaguchi (“Drive My Car”), Ruben Östlund (“Triangle of Sadness”) and 2019’s winner, Bong Joon Ho (“Parasite”) — launched their journey with a major prize at Cannes. (Even “Another Round,” which earned a directing Oscar nomination for its Danish filmmaker, Thomas Vinterberg, was announced as an official selection of the pandemic-canceled Cannes Film Festival of 2020.)

Cannes, it’s worth noting, screens only a fraction of world cinema’s annual bounty. But its consistent influence at the Oscars — an event often assumed to be dominated by Hollywood-made, English-language movies — carries mighty symbolic weight, particularly on the heels of a year that was often written about, reductively, as being about “Barbenheimer” and nothing else. The mere fact that so many voters cast their ballots for a movie as purposely, defiantly uncommercial as “The Zone of Interest” should be heartening news to anyone who loves the Oscars but loves cinema even more.

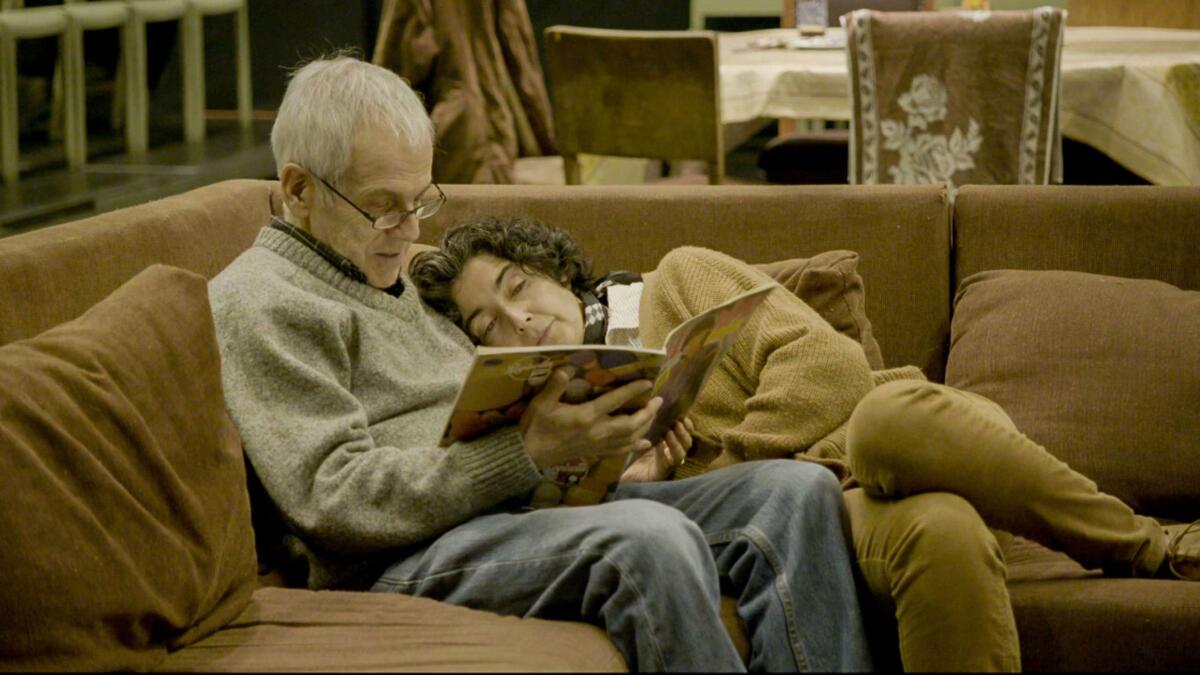

But perhaps the most startling and encouraging evidence of the academy’s growing internationalism could be found in another area of the nominations altogether. I’m speaking of the documentary feature category, which notably omitted some of the year’s most laureled American nonfiction films (“American Symphony,” “Still: A Michael J. Fox Movie,” “Beyond Utopia”) in favor of the most internationally wide-ranging selection of doc nominees I can remember. The nominees are “Bobi Wine: The People’s President,” Moses Bwayo and Christopher Sharp’s chronicle of Wine’s campaign for the Ugandan presidency; “The Eternal Memory,” Maite Alberdi’s moving portrait of a Chilean couple grappling with the challenges of Alzheimer’s disease; “Four Daughters,” Kaouther Ben Hania’s fragmentary story of a Tunisian family torn apart; “To Kill a Tiger,” Nisha Pahuja’s film about an Indian family seeking justice after a sexual assault; and “20 Days in Mariupol,” Mstyslav Chernov’s intensely harrowing dispatch from the early days of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

I haven’t seen them all yet, but plan to do so soon. Catching up with Oscar nominees you’ve missed, after all, is another reason the interregnum exists; even this seemingly late in the process, a sense of discovery is possible. It’s why I find myself unable to be (entirely) cynical about the Academy Awards, which, for all the mockery they court and sometimes deserve, can still do the essential work of bringing great, undersung movies to broader public attention. That’s another reason why “snub” grates as a concept: The people most convinced they know what should have been nominated so often have the least knowledge of the brilliant, lesser-known work that’s out there.

In movies and awards, in criticism and in art, I’ve always believed that a little humility can go a long way — which is another way of saying, I have no idea what’s going to win. But right now, a less insular motion picture academy, one that acknowledges the vitality of cinema as a global medium, already feels like its own kind of victory.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.