Review: ‘Killers of the Flower Moon’ is a powerful historical epic — and a qualified triumph

- Share via

Martin Scorsese’s “Killers of the Flower Moon” begins in the heavily shrouded darkness of an Osage tribal ceremony, a somber occasion that marks the passing of a much-cherished way of life. White American settlers have driven the Osage from Kansas into what is now northeastern Oklahoma, an act of displacement that they commemorate by burying a peace pipe. But their lament will soon give way to celebration: Into the earth goes the pipe and out comes a great gush of oil, raining down on the Osage in a sequence of surreal, joyous revelry. This is the first and last time they will appear this carefree, dancing against a wide-open landscape that will soon be dotted with oil derricks, looming emblems of America’s industrial and capitalist boom.

Suddenly rich beyond their wildest dreams, the Osage will also find themselves extorted, exploited, hunted and persecuted in ways they scarcely could have imagined. By the time “Killers of the Flower Moon” draws to a close, a few decades and nearly 3½ hours later, the toll of that persecution will have been amply measured: in the hundreds of millions stolen from Osage coffers, and in the steady, systematic pileup of Osage bodies. The qualified achievement of this grim and enveloping movie, which Scorsese and Eric Roth adapted from David Grann’s superb 2017 nonfiction book, is to illuminate a far-reaching conspiracy from the inside, to give cinematic force and emotional weight to what was once a Prohibition-era footnote in the long, brutal history of Native American genocide.

Since that history has seldom been given its due or even the time of day in American movies, the significance of Scorsese’s accomplishment can hardly be overstated, even if the film itself, like much of the director’s work, is susceptible to both knee-jerk dismissals and florid overpraise. Part of the fascination of “Killers of the Flower Moon” is that it is both the highly skilled culmination of a master’s output and a wobbly first step in a new direction. It is, on one level, a crime thriller built from familiar Scorsesean elements: demanding father figures and feckless heirs, treacherous husbands and neglected wives, oafish goons and ruthless assassins, Leonardo DiCaprio and Robert De Niro. But within Scorsese’s own oeuvre as well as the larger context of American cinema, it also charts out fresh and historically significant dramatic terrain.

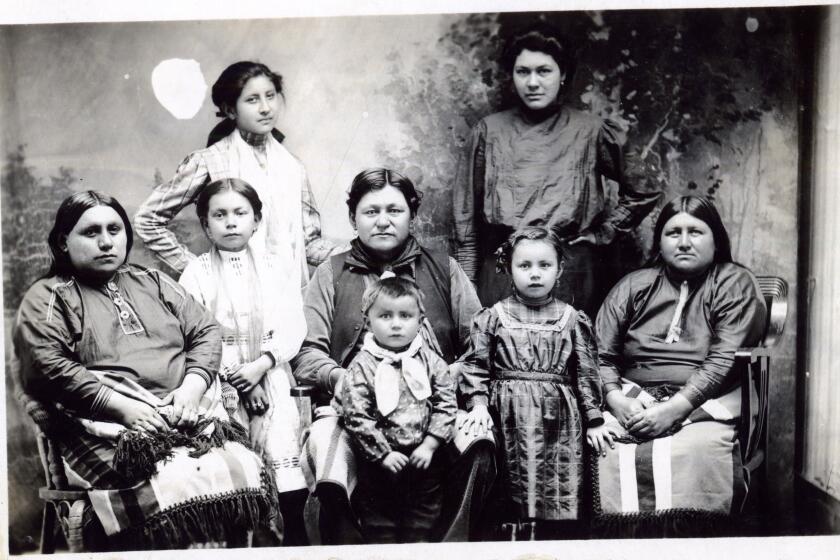

By the 1920s, that terrain, once a sparsely populated stretch of Osage reservation, is covered with bustling small towns, those towering derricks and an awful lot of cattle. It is also, or at least seems to be, a thriving bicultural boomtown, where Osage men and women live in well-appointed houses, own expensive automobiles and wear a mix of traditional tribal garb and modern dress; some also employ white servants. The extravagance of their lifestyle inspires much public curiosity, something Scorsese conveys, in an energetic period flourish, with reams of black-and-white mock-newsreel footage.

Tellingly, though, he brings us into this strange new world through the outsider eyes of Ernest Burkhart (DiCaprio), a feckless World War I veteran with an injured gut, an aw-shucks grin and an insatiable appetite for women and money. That’s no crime, of course. But from the moment Ernest arrives in the Osage town of Fairfax and sits down with his uncle, a cattle rancher and revered community fixture named William K. Hale (De Niro), it’s clear that the younger man’s lusts are being cultivated in a treacherous direction.

With a demonic twinkle, Hale shoves his nephew toward the town’s many wealthy Osage women, among them a quietly poised beauty named Mollie Kyle (an outstanding Lily Gladstone). Like all the Osage, Mollie has no direct control over her wealth; she’s been assigned a white financial guardian and declared “incompetent” by the U.S. government, though that’s the last word you’d use to describe someone of her grace and self-possession.

When Ernest starts chauffeuring her around town, Mollie is guarded but receptive to his flirtations. She knows that this “coyote” wants her money, but she also senses and returns his very real ardor and affection. They soon marry in a gorgeous wedding sequence that suggests a Sooner State remake of “The Godfather,” buoyed by the exquisite details of Jacqueline West’s costumes and the earthy, panoramic sweep of Rodrigo Prieto’s cinematography. In this scene and others, Prieto places Ernest and Mollie side-by-side in a symmetrical widescreen frame — a visual gesture that conveys the depth of their intimacy but also positions them as equals. It may be a white man’s world, but here in Osage territory, Mollie’s riches and regal bearing tell a thrillingly different story.

The prevalence of interracial marriage, plus the rare spectacle of white subservience and Indigenous largesse, is the kind of inversion of the social statuo quo that clearly fascinates Scorsese. Like some of his most elaborate period re-creations — the high and low visions of 19th-century Manhattan in “The Age of Innocence” and “Gangs of New York,” the feudal Japan of “Silence” — the Oklahoma we see is more than just a splendid piece of scenery (although it is certainly that, thanks to production designer Jack Fisk, who worked similar magic with the parched California oil country of “There Will Be Blood”). As the camera navigates crowded streets, seedy gambling parlors and the swirling domestic chaos of Ernest and Mollie’s home, Scorsese doesn’t just achieve a sense of place; he also pulls off, not for the first time, a passionate and meticulous feat of cultural anthropology. He brings an entire bygone era to rich, teeming life, just before he chokes it off with an all-consuming stench of death.

Even as she and Ernest start a family, Mollie finds herself losing her own relatives, in what somehow feels like both agonizing slow-motion and shatteringly rapid succession. Over the course of a few years, her sister Minnie (Jillian Dion) and her mother, Lizzie Q (the steel-gazed Tantoo Cardinal), succumb to a mysterious “wasting illness.” Another sister, Anna (Cara Jade Myers, fiercely memorable), is found shot to death in a nearby pond, one of several grisly homicides memorialized in a stark, disturbing montage. Most of these Osage deaths, we’re told, were never investigated, suggesting breathtaking levels of official corruption at a time of already rampant lawlessness. But the big picture is always distressingly clear: White people are killing Indigenous people for their “headrights,” their legal claims to this oil-rich land, and they are doing so with strategic patience, chilling ruthlessness and utter impunity.

The fundamental obviousness of what’s happening accounts for why, unlike Grann’s book, which disgorged its secrets gradually, Scorsese and Roth pretty much clue us in from the outset. That’s a bold stroke for a 206-minute movie, even one that, as cut together by Scorsese’s longtime editor, Thelma Schoonmaker, keeps its grip on your attention even when it sometimes gets lost in its own conspiratorial labyrinth. The specifics of who killed whom aren’t always apparent or, for that matter, coherent. (Call it disorganized crime.) You learn to follow the plot not just through the names but also the faces of various low-level thugs and lunkheads, vividly played by actors including Scott Shepherd, Louis Cancelmi, Tommy Schultz and Sturgill Simpson.

Speaking of faces: Even if Hale didn’t give off such conspicuous John Huston-in-“Chinatown” vibes (or have an occasional tendency to say the quiet part out loud), it’d be impossible to ignore the darkly iconic associations De Niro pipes in from “Goodfellas,” “Cape Fear,” “The Irishman” and other classic Scorsese joints. You perceive Hale’s true colors immediately through those associations, just as you can see Ernest’s venality through DiCaprio’s immediately recognizable brand of boyish corruptibility. The sublimated tension of the Hale–Ernest dynamic, embodied by two Scorsese veterans in fine form, is so clear and legible that it sometimes runs the risk of pushing everyone else to the narrative periphery.

You will wish for more immersive, interior glimpses of Osage life, beyond the sobering mass gatherings led by tribal elders terrified by the epidemic of killing in their midst. You may also wish for more of Jesse Plemons as Tom White, the politely dogged investigator who cracks the case with his intrepid undercover team. One of the calculated casualties of Scorsese and Roth’s script is the origin story that Grann’s book spun for the FBI, which counted the Osage killings among its groundbreaking early homicide cases. It’s not hard to imagine the sprawling detective procedural Scorsese might have wrought from that jettisoned material (or to dream of a surreal DiCaprio-meets-DiCaprio moment between Ernest Burkhart and J. Edgar Hoover). Instead he treats White’s investigation as something of a dramatic redundancy, a summary of a mystery whose solution has been clear all along.

The more compelling puzzle in “Killers of the Flower Moon” isn’t a question of whodunit. It’s the emotional and psychological ambiguity at the heart of Ernest and Mollie’s marriage, a parasitic bond that quivers with eroticism, swoons with tenderness and finally reads as an irreducible metaphor for Indigenous destruction. A shudder convulses the picture when Mollie, who’s diabetic, falls gravely and suspiciously ill. You search for clues to her condition in Ernest’s face, twisting itself into a horrified, self-loathing perma-frown. But it’s Mollie’s visage, radiant and eerily becalmed even when she’s bedridden, that keeps drawing your gaze; she’s the faint-flickering beam of light in a story of near-impenetrable darkness.

An actor who can set off more emotional reverberations with a barely cracked smile than some performers manage in an entire monologue, Gladstone (“Reservation Dogs,” “Certain Women”) is so extraordinary here that she nearly succeeds in blunting — and, at times, productively complicating — the showier, grabbier interplay between De Niro and DiCaprio. Her performance is astonishing, even if her character is too dramatically sidelined, especially in the later passages, to shoulder the movie’s much-vaunted representational ambitions. To describe Mollie as the story’s wounded conscience is not quite the same thing as saying she occupies its narrative center, which she does not. Apart from Mollie’s strongest scenes and Lizzie Q’s occasional grim deathbed visions, the movie seems curiously reluctant to penetrate the psychology of its Osage characters — a reluctance that feels like timidity, respect or maybe a mix of both.

I think that lapse explains some of the anxiety that has swirled around “Killers of the Flower Moon” since even before it premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in May. Much has been made about the armies of Osage consultants enlisted to ensure an authentic depiction of Indigenous life. While that commitment bespeaks admirable care and sensitivity, it’s also clearly designed to offset the apparent optical setback of having a white filmmaker, even a white filmmaker as justly revered as Scorsese, tell an epic tale of Native American displacement and destruction. Even if we reject the usual art-deadening canards about who is and isn’t allowed to tell whose story, it’s worth noting that one of the film’s most poignant and surprising scenes finds Scorsese himself addressing that very question. With wit and humility, he implicates himself in a vast storytelling tradition — one that encompasses radio and theater as well as cinema — that has continually exploited, marginalized and glossed over images and narratives of Native American life.

Scorsese’s new film ‘Killers of the Flower Moon,’ about the murders of Osage people over oil and land in Oklahoma, doesn’t begin to describe the depraved injustices inflicted on the tribe by the U.S. government.

That humility is crucial, and moving in its own right. Whatever its triumphs and missteps, revelations and blind spots, “Killers of the Flower Moon” comes by them all honestly. It has been made in rightful hope that the American crime epic, a genre Scorsese has pushed to peerless heights, can still open an audience window into a richer understanding of culture and history. It also brushes up against some of the genre’s not-uncommon limitations, including a tendency to privilege flamboyant villainy over heroic resistance, violence and excitement over the quiet and the quotidian.

And if “Killers” miscalibrates its balance of perspectives, it also discovers, in the luminous recesses of Gladstone’s performance, a quality of contemplation that beautifully suffuses and modulates Scorsese’s faster, more frenetic rhythms. This is the work of a filmmaker who, with 80 years and a permanent place in the pantheon under his belt, has nothing left to prove and entire worlds still to discover.

'Killers of the Flower Moon'

Rating: R, for violence, some grisly images and language

Running time: 3 hours, 26 minutes

Playing: Starts Oct. 20 in wide release

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.