- Share via

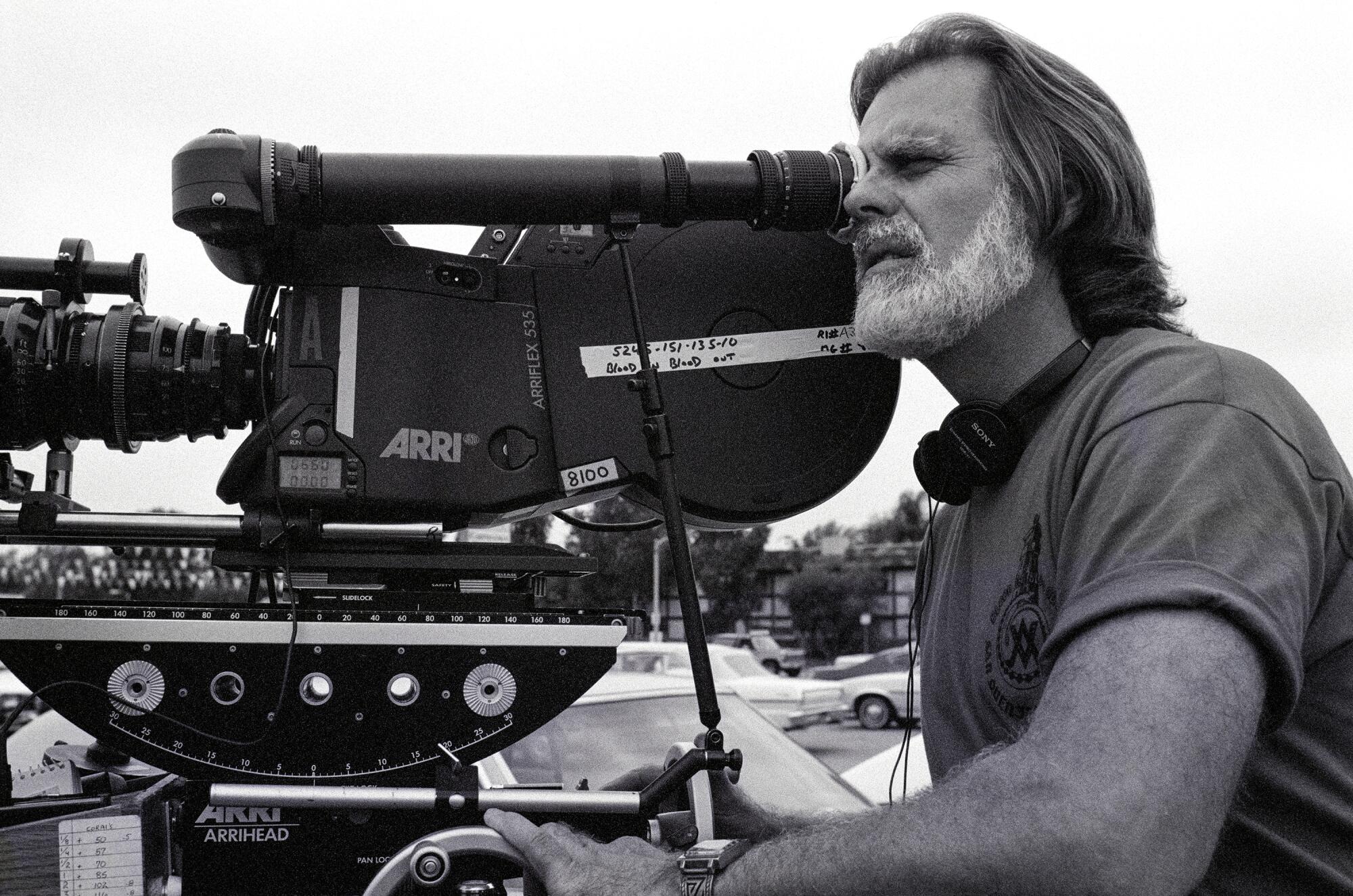

On a recent evening out with a friend at La Cita Bar, the downtown L.A. nightclub that has historically catered to Latino patrons, Oscar-winning director Taylor Hackford made a bold statement.

“I bet you that 90% of the people in this bar right now have seen ‘Blood In Blood Out,’” he told his companion, who thought the proclamation was a stretch. Hackford turned to the two Latino men sitting next to him and asked if they’d ever heard of the movie. “Cruzito is my favorite character!” one of them replied enthusiastically. Point proved.

Akin to “The Godfather” in its scope and themes, “Blood In Blood Out,” which turned 30 this month, stumbled at the box office but was saved from obscurity by fervent Latino audiences, who reclaimed it as a cornerstone of their representation in cinema.

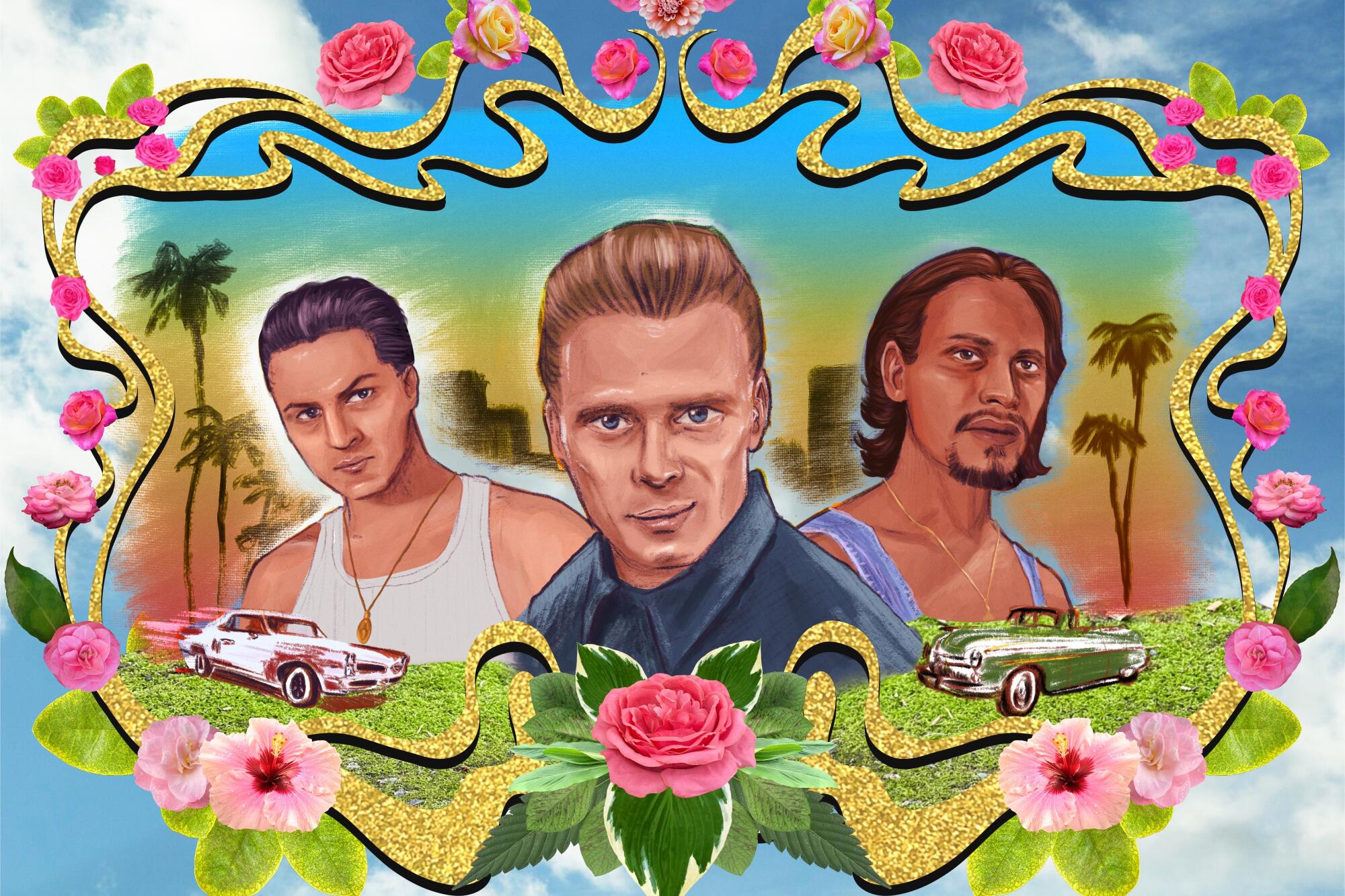

Released theatrically in 1993 as “Bound by Honor,” Hackford’s ambitious, decade-spanning story, set between 1972 and 1984, featured three up-and-coming Latino talents — Jesse Borrego, Benjamin Bratt and Damian Chapa — as inseparable members of the fictional Vatos Locos gang in East Los Angeles whose paths divert into incompatible directions.

There’s Cruz Candelaria (Borrego), an auspicious painter who develops a drug problem following a tragic incident; Paco Aguilar (Bratt), a Golden Gloves boxer turned “traitor” after becoming a police officer; and Miklo Velka (Chapa), a white boy with Mexican ancestry whose desperation for acceptance lands him in prison, where he quickly rises to a leadership position within La Onda, a dangerous Chicano crime family.

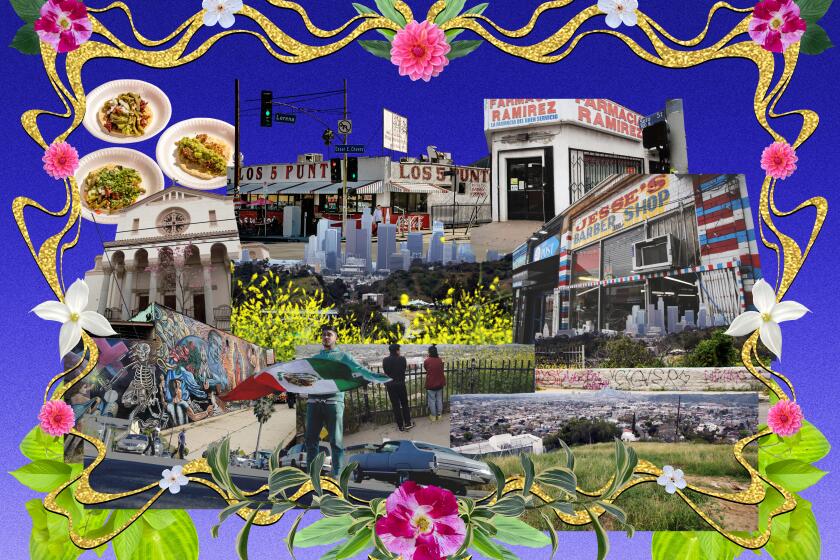

30 years after its release, ‘Blood In Blood Out’ still holds cultural significance to the Latino community. Here is a list of some of the locations depicted in the film, in East L.A. and beyond.

Credit for the lived-in sensibilities of the film goes to Jimmy Santiago Baca, a New Mexico poet who honed his craft in la pinta (slang for prison). Chapa refers to him as a “modern-day Chicano Oscar Wilde,” while Borrego calls him “the Chicano Shakespeare.”

Together with paintings by San Antonio artist Adan Hernández, including the mural “Carnalismo” in the final scene, as well as cinematography by Gabriel Beristain, the collective force of these Chicano talents conceived a wide-ranging portrait of the community “in its many subtleties and forms,” as Borrego puts it.

“It’s a beautiful panoramic view of who we are as a people, in our abundance rather than our exclusivity,” said Baca.

On the occasion of its 30th anniversary, The Times reminisced about the making, release and enduring timelessness of the Chicano classic with some of the crucial artists involved.

A Disney-backed Chicano Sistine Chapel

In the wake of the box-office success of the 1987 Ritchie Valens biopic “La Bamba,” which Hackford produced, the director envisioned developing other projects aimed at an eager Latino audience.

Edward James Olmos reached out to Hackford with a screenplay titled “Blood In Blood Out,” written by Floyd Mutrux and based on a story by Ross Thomas, which Olmos hoped to turn into his directorial debut. The saga traced the foundation of La eMe (Mexican Mafia), the notorious criminal organization formed within the California prison system.

“With ‘La Bamba,’ there was no controversy, with ‘Blood In Blood Out’ there certainly would be, but I still felt it was a compelling piece,” Hackford recalled.

The fundamental elements of the story, which takes place in East L.A. and San Quentin State Prison, were already present then: Three young men (two half-brothers and a cousin), each with their respective struggles of identity, set against the backdrop of the emergence of a powerful crime family. For Hackford, however, something was lacking.

“That format was there. It was the voice that I had a problem with,” said Hackford.

A native of Santa Barbara, Hackford had grown up around the Mexican American community, and in his years as a KCET reporter he often accompanied colleague Jesus Treviño to cover East L.A. Those experiences, he believes, convinced him that the text didn’t ring true. Still, he trusted Olmos’ instinct and reputation.

Citing creative differences, among them his decision to bring a co-director on board, Olmos eventually moved on to pursue what would become “American Me” with a different script about the same subject matter. Hackford decided he’d direct “Blood In Blood Out” himself, but he desperately needed an ally with close ties to the world where the drama unfolds.

On the recommendation of Luis Valdez, the noted playwright and director of Chicano classics such as “La Bamba” and “Zoot Suit,” Hackford reached out to poet Jimmy Santiago Baca to rewrite the script. But a guarded Baca wasn’t interested in working for Hollywood. It was only after Hackford agreed to take a trip to New Orleans to get to know Baca over copious drinks that the scribe accepted. And so Baca began to transfigure his firsthand accounts from 25 years of institutionalization, six of them in federal prison, into the lyrical fabric of the film. (Baca shared a writing credit with Jeremy Iacone.)

“I thought, ‘If I can do something for my raza, if I can write something that’s true to the bone, pues go ahead and do it,’” recalled Baca.

“Jimmy was so important to this because everybody else, including me, we were posers,” said Hackford. “We’re in the entertainment business, but Jimmy was in the joint. He knows about it because he lived it.”

Baca moved from Albuquerque to L.A. to immerse himself in the city’s Chicano culture. From the onset, the dialogue was essential to Baca’s intent.

“I wanted to use this buoyant Chicanismo language that we speak; the beautiful way that we transform language to meet our own cultural needs, our own legacy and our own inheritance from our antepasados,” Baca explained. “It was like giving the actors something that they knew already instinctively: the rhythms of the language, the metaphors, the imagery, the cábula, and how much meaning all that carries for us.”

Once fleshed out, Baca believed it had the potential to become “the Sistine Chapel of how we are trying to integrate into American society.” Each character drew from the people he’d known during his time incarcerated. And while he sought to stay faithful to the story of Joe Morgan, La eMe’s first non-Latino member, he did so without explicitly referencing him or any of the factions involved by name. La eMe became La Onda. The Aryan Brotherhood was the Aryan Vanguard.

Encouraged by the more than $50 million that “La Bamba” had amassed, Hollywood Pictures — a now-defunct label under the Walt Disney Co. umbrella that was run by Cuban American executive Ricardo Mestres — expressed interest in producing “Blood In Blood Out.”

Hollywood Pictures had been created by former Paramount Pictures executives Jeffrey Katzenberg and Michael Eisner, who knew Hackford from his Academy Award-winning drama “An Officer and a Gentleman.” Suddenly, a violent tale of loyalty, honor and carnalismo — brotherhood — among Chicanos became a Disney-backed, $17-million feat.

When the three carnales came to the Eastside

It was inside a casting office on Hollywood and Vine more than three decades ago that the life of actor Damian Chapa took an indelible turn.

There to audition for a part in a film called “The Bridge,” Chapa was asked if he would instead read for the role of Miklo Velka. Intrigued, he read the sides, which described the character as a “blue-eyed Chicano,” the child of a Mexican mother and an Anglo father.

“I automatically said to myself, ‘How is this happening?’ My whole life I was trying to fit in with my Chicano culture, the same exact way that Miklo was,” said Chapa.

Raised in Robstown, Texas, Chapa embodied the dichotomy of Miklo: His father was of Mexican descent and his mother had Irish heritage. His genuine grasp on the emotional struggles of the character set him apart from the many actors in consideration.

Miklo has become so entrenched in the fiber of his being that in conversation Chapa often speaks about himself and the character as if they were one and the same. In talking about Chapa, Hackford does the same: “I keep calling Damian ‘Miklo,’ because he is.”

The Latino community’s unending fondness for Miklo has granted Chapa the sense of belonging he longed for growing up. “People say all the time, ‘Well, you’re not Miklo,’ but I go, ‘Maybe I’m not Miklo, but I understand Miklo more than a lot of people,’” Chapa said.

Author and journalist Shea Serrano, who dedicated his most recent book, “Movies (and Other Things),” to Miklo, identifies with the character as a Mexican American who doesn’t speak Spanish and who grew up feeling not Mexican enough. “When I watched the movie for the first time, I was like, ‘I know all of this stuff that he’s feeling,’” recalled Serrano.

By the time Chapa officially joined, the other two leads had been cast. Jesse Borrego came first. Originally from San Antonio, Borrego had starred on the popular series “Fame” and was considered for the role of Bob in “La Bamba.” Fully bilingual and already an outspoken advocate for the dignified representation of Latinos in media, he became a key ally for Hackford throughout the production to avoid any falsehoods.

“Through Cruzito and the exemplification of Chicano art, I thought I could show how a chavalon from the barrio was just as talented as any of your mainstream artists,” explained Borrego. “I was the proof. I was already a successful actor in the business.”

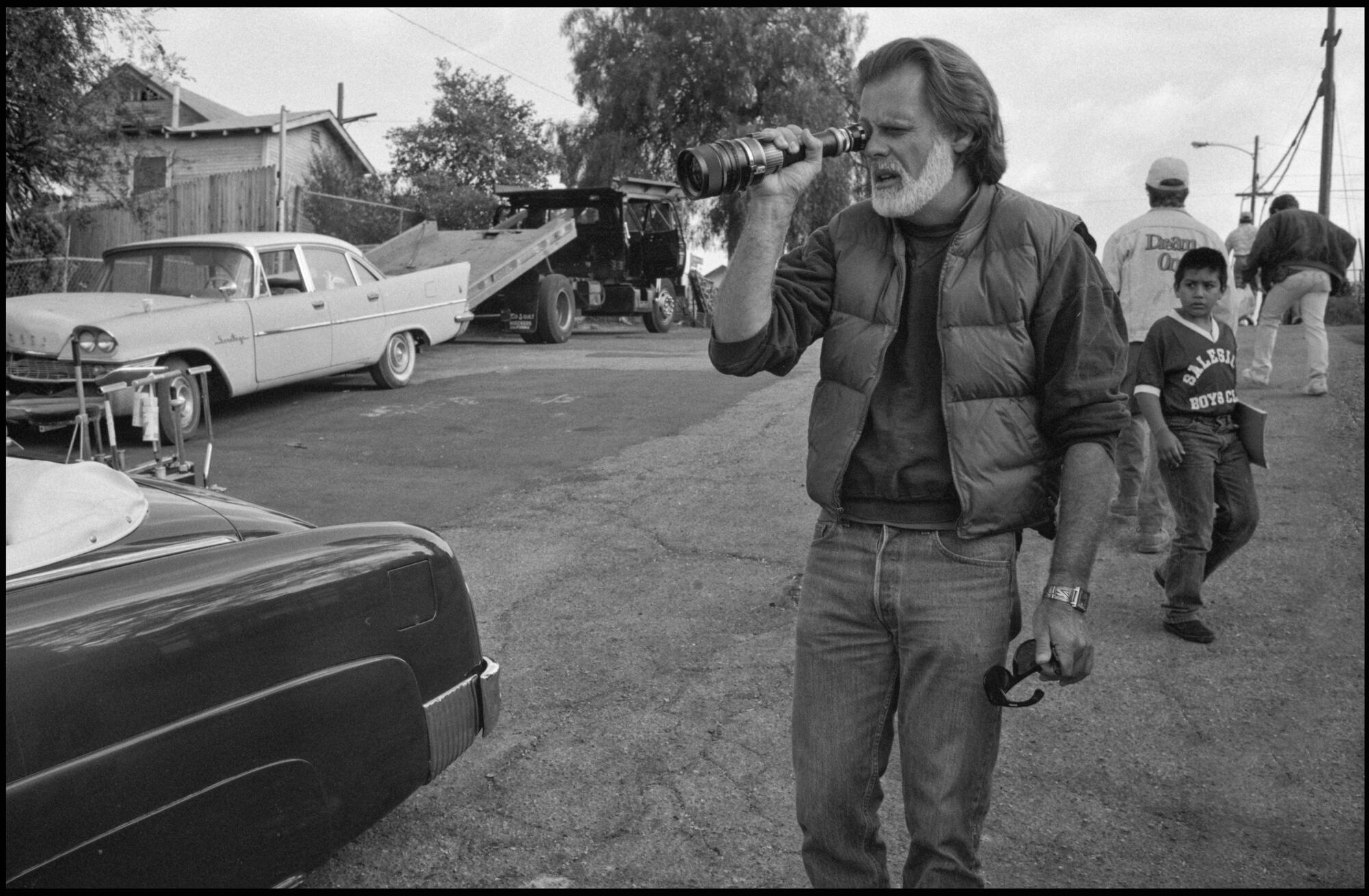

Concerned with authenticity, having cast three actors from outside Los Angeles, Hackford asked them to move together into a house near Hazard Park so that they could soak up the neighborhood and interact daily. In turn, the director also moved the film’s production office to Soto Street and Brooklyn Avenue (now Cesar E. Chavez Boulevard).

Every night, Borrego would host “Vatos Locos Tutorials,” where he and his co-stars would go over the screenplay and instruct Bratt and Chapa on the colloquialisms of Caló (Chicano jargon). Borrego’s efforts had great impact.

“If I attained any degree of success in my portrayal within this film, a great deal of the credit has to go to what I learned from Jesse Borrego,” said Bratt. “Not only about the notion of carnalismo but about what it means to be a true and giving artist as an actor.”

Living under the same roof, the three of them forged a fraternal bond. Bratt appreciates that the experience happened early in his career. More established actors, he thinks, wouldn’t have as easily accepted to go on this adventure months before filming began.

“There was a kind of alchemy created in those two months living together that really bore out on the screen,” said Bratt. “The relationships that you see reflected in the early part of the film feel very authentic because it was based on real experiences together.”

La pinta and the helpful wardens

Contrary to the apocryphal legend that has circulated over the years, neither Hackford nor Baca was ever in contact with members of La eMe. Although the director considered it after learning that Olmos, working on “American Me,” had done so, Baca vehemently advised him against it.

“Jimmy said, ‘You do not go to those people. They’re like every other crime family: If they do you a favor, they own you,” recalled Hackford.

Still, Hackford wanted to shoot at San Quentin State Prison. It was the veracity of Baca’s writing that made it possible. The warden at the time, Danny Vasquez, read the screenplay and was so impressed with its truthfulness that he granted them access.

Once they had obtained permission to shoot, Hackford enlisted Bobby Vazquez, a warden at Rahway State Prison in New Jersey, to interview hundreds of inmates at San Quentin and determine who were best suited to participate as extras. In exchange for their participation, the production offered meat with every meal, in addition to contributing to the prison’s library and the weight yard.

“They were happy to get involved because the story was a validation of their manhood as human beings, and not as criminals, but as human beings,” said Baca.

Portrayed by Enrique Castillo, Montana, the leader of La Onda and a key character during the prison sequences, was inspired by the older inmates who took Baca under their wing. Because of them, Baca learned to read and write while behind bars and later earned a living writing letters for other inmates.

“I met a lot of guys in prison that really were like Montana. They wanted to further the importance of la raza in a cultural way,” said Baca. “They wanted to get away from the idea that we were a criminalized population and believe that we could, even within that environment, still stay human and learn how to be compassionate toward each other.”

On the botched release of ‘Bound by Honor’

In 1992, the L.A. riots erupted while Hackford was editing the film. The director says the civil unrest worried Michael Eisner, the head of Hollywood Pictures.

“Eisner was really frightened that a violent crime drama might generate bad press for Disney. I wasn’t happy about it, but I did kind of understand it,” said Hackford. “Still, I was fighting for my film. What Disney agreed to was to test it.”

The marketing team screened the film in a number of predominantly Latino cities without incident. But during the final test showing in Las Vegas, a fight broke out in the lobby. “That was enough for Eisner to say, ‘Well, there it is. There’s the proof. There’s going to be violence,’” Hackford recalled.

Thankfully for the film, Frank Wells, then president of Walt Disney Co., had seen and liked it. They would release it but under a less controversial, seemingly more uplifting name that, to their mind, wouldn’t incite violence: “Bound by Honor.”

“From the time that [Hernán] Cortés stepped in the peninsula down in Mexico, the Europeans have done nothing but spill blood, so you’d think it would be familiar to them, but when we decided to use it, they’re like, ‘No,’” said Baca.

Before the Las Vegas incident, the studio’s projections estimated the picture was on track to gross $40 million. Upon its release on April 16, 1993, with a new title and diminished promotion, the film made only $4.5 million.

Hackford had enough footage to tell the story in two parts. But his epic had to adapt to the requirements of the studio. His vision had to be compressed to just under three hours for the theatrical cut. A slightly longer director’s cut later saw the light on DVD.

“We just kept trying to keep our integrity from selling out and making it fit into the frame that Hollywood Pictures needed it to fit in for the theaters,” said Baca. “And because of the theme and because of the content, they just kept shying away from it.”

Film critics at the time were not high on the film. Olmos’ “American Me” had been released a year earlier, which prompted comparisons. Some argued the story had already been told. Both productions had been in competition since their inception — they were shot around the same time in 1991 — and both raised concerns from advocacy groups such as the National Hispanic Media Coalition regarding their depiction of Latinos onscreen.

L.A. Times critic Kenneth Turan deemed it “three hours of violent, cartoonish posturing incongruously set in the realistically evoked milieu of East Los Angeles.” The New York Times published a more evenhanded if still unfavorable take by Vincent Canby. The review said that Hackford’s movie presented its characters’ lives as “an unending succession of moments of high melodrama” but still praised its “redeeming sincerity.”

Given the scope of the narrative, the resources at hand, and the cast being a “who’s who of who was working at the time within the Latino community,” as Bratt puts it, the actors had high hopes for what “Blood In Blood Out” could do not only for their individual careers but for Latinos in the entertainment industry. The illustrious ensemble featured the likes of Lupe Ontiveros, Danny Trejo, Raymond Cruz, Valente Rodriguez and Ray Oriel, to name a few.

“We really thought we were going to win Academy Awards,” said Borrego. “We really thought that we were going to break the barriers. It was unfortunate that in the business decisions that studios make, we got left behind.”

And still the Vatos Locos live on

Chapa saw his career prospects vanish following the initial failure of “Blood In Blood Out.” Few people had seen it on the big screen, and thus he felt nobody knew whether he was any good. They simply didn’t see him all. But that changed.

“All of a sudden, about two years later, some kid came up to me and he said, ‘I saw you in a movie.’ And I was like, ‘This is great. Somebody saw me in a movie,’ It was the first thing I’d done. And I said, ‘Where’d you see it?’ He says, “I got it at Blockbuster.’”

Chapa remembers hearing that “Blood In Blood Out” became the most stolen tape at Blockbuster ever. Although no evidence exists to corroborate this assertion, there’s no denying that it was thanks to home video, where the film was released with its original title, that people discovered it.

It was on VHS that Serrano first watched the film, which he considers “the best movie that’s ever been made,” as a teenager in San Antonio. That the film still enjoys enormous popularity among Latinos, Serrano and the actors think, derives from the union of Hackford’s seasoned directorial skills and Baca’s singular artistry, a partnership of mutual admiration.

“It felt like [Hackford] was trying to make Jimmy’s script more than he was trying to make Taylor’s movie,” said Serrano. Baca agreed, and credited Hackford for fighting tooth and nail so that the integrity of the story and its Chicano DNA were never compromised.

Those who fixated on the violence onscreen misunderstood the motivation behind it, Baca believes, which was not to glorify criminal organizations but to expose how people living in an environment that is not nourishing, where political and economic injustices abound, react to those conditions in order to survive and to protect their families.

“While some tried to shy away from the crime, the gangs, the drugs and prison, I embraced it and I dove into it. And I showed you the compassion and the suffering and the sorrow that we experience in trying to navigate these obstacles, trying to get the respect that we deserve in American society,” said Baca. “And a lot of people really got that.”

Shockingly, “Blood In Blood Out” isn’t legally streaming on any platform, yet clandestine YouTube uploads of the entire film continue to make it accessible for its fans — one version, said to be in 4K quality added less than a year ago, has garnered more than 4.4 million views.

“They’re leaving money on the table,” said Hackford. He believes the suits at Disney are not aware of what they have in their hands and its cultural relevance. But the people know.

It’s a sentiment shared by stand-up comedian and podcaster George Perez, who says that the most downloaded episode of his podcast — “It’s not even close!” — was when he had Carlos Carrasco, the actor who portrayed Popeye, on as a guest.

“Imagine if they streamed it, how much money [Disney] would make!” said Perez. “It would easily be the No. 1 movie if you put it on Netflix, I guarantee you it’d be the No. 1 movie for at least a month!”

Such is the draw of “Blood In Blood Out” that the film made stars out of inanimate objects. One emblematic aspect for which Hackford takes sole credit is the invention of the symbolic El Pino, the bunya pine tree that became an East Los landmark through the film. As soon as he saw it while walking out of the Los Cinco Puntos market, the director realized that it could be the place where the trio would meet. The name, however, was Baca’s idea.

In 2021, Times columnist Gustavo Arellano reported that fans of the film flocked to the now iconic landmark when rumors spread online that a developer was planning to cut it down. The pending demise of El Pino turned out to be hearsay, but the endearment from the public was all real.

“The powers that be didn’t support the film, but it was the people who gave it longevity. It was the people who gave it popularity. It was the people who consistently said, ‘We love this film, it speaks to us,’” said Baca. “There’s no greater satisfaction when you’re a writer than when you touch somebody’s heart in a way where it validates their life experience.”

Borrego, who dubbed his own lines in the Spanish-language version titled “Sangre por Sangre,” now often meets fans of all ages and nationalities at pop culture conventions or outdoor markets around the country. “The endurance of the film means that we accomplished our job,” said Borrego. “Our award was to be with the raza for 30 years.”

Meanwhile, Bratt recalls ordering a latte at a coffee shop in L.A. , and when the drink came to his table it had “Vatos Locos Forever” written in foam. His brother, Peter Bratt, regularly messages him photos of the unlicensed merchandise he sees in the street markets of the Mission District in San Francisco. Everything from T-shirts to blankets emblazoned with the characters’ faces can be found anywhere Latino vendors are.

“I’ve been in a lot of memorable films, a lot of films that are beloved by audiences, but none greater than this one in terms of the quotability of the lines,” added Bratt.

For Chapa, there’s one Miklo line that sums up how this experience forever altered his path. “It’s the kind of line that lives forever,” he said. It’s a searing declaration that comes late in the film as Miklo inches closer to becoming El Mero Mero, and which in turn could also apply to how, despite being dismissed to oblivion in its day, “Blood In Blood Out” couldn’t be kept down: “When you expect nothing and you get everything, that’s destiny.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.