At comedy clubs, ‘everyone knows Jo Koy.’ With ‘Easter Sunday,’ America will too

- Share via

It’s not April, but “Easter Sunday” is right on time for Jo Koy.

“Summers are all about your blockbusters, right? We got ‘Top Gun: Maverick,’ ‘Minions[: The Rise of Gru],’ ‘Bullet Train’ — and the studio’s like, ‘We’re putting Jo Koy’s movie in that slot!’ What a beautiful moment to celebrate,” says the comedian, laughing happily.

“I just passed another billboard in front of Universal Studios. And as I left that, there’s another one. They are full-on supporting this movie.”

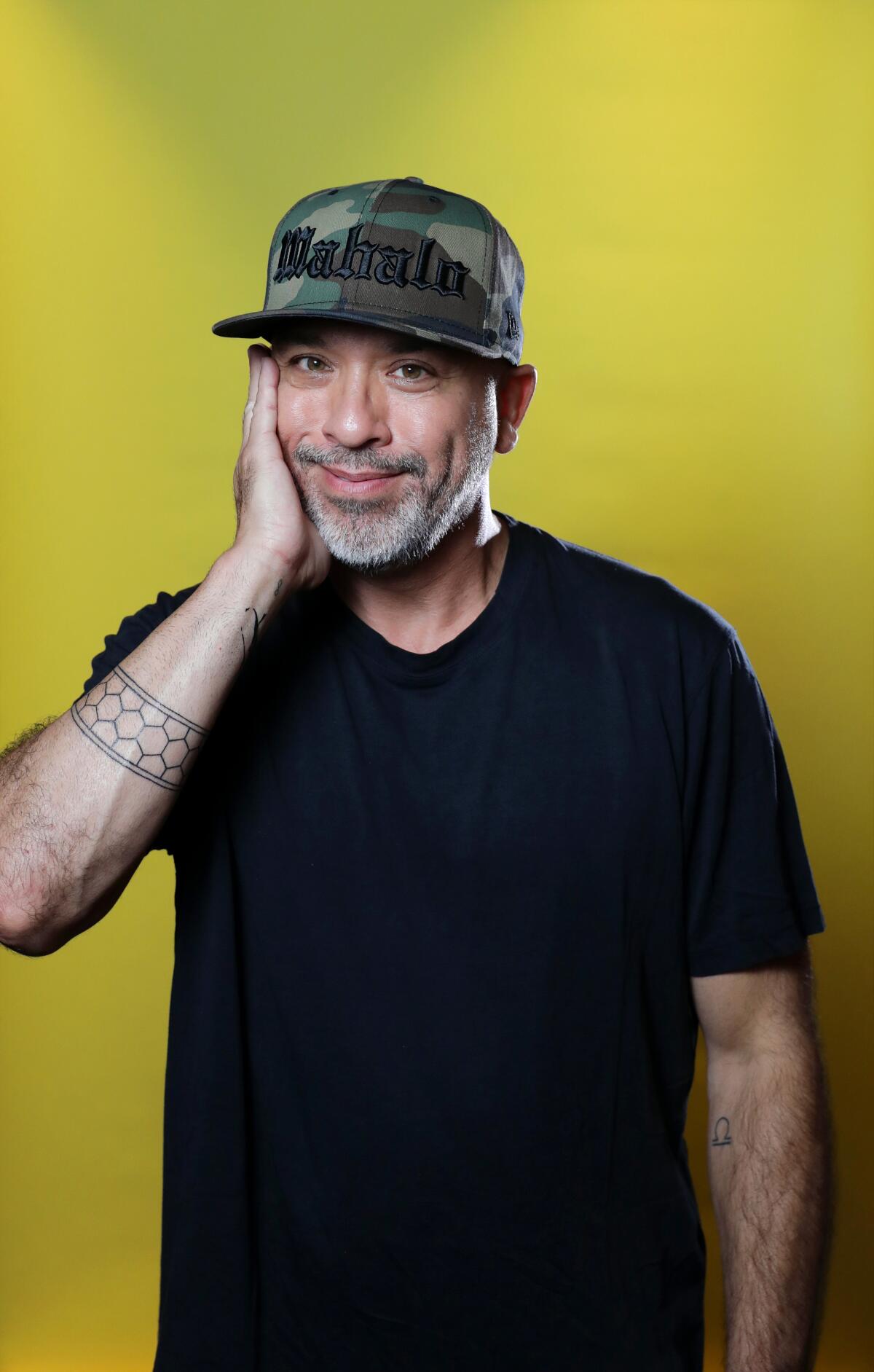

It has got to be pretty heady. Koy, who once hustled to get people into shows he wasn’t even headlining, eventually advanced to selling out arenas and creating four stand-up specials (two on Comedy Central, two on Netflix). Now he’s No. 1 on the call sheet in a feature film and seeing his face on billboards and bus stops all over Los Angeles. The movie, “Easter Sunday,” is all the more improbable because it’s a major studio comedy (Universal via DreamWorks, Rideback and Amblin Partners) about a Filipino American family.

“If they’re willing to take a chance for my culture and my people to have a voice, then I’m gonna do whatever it takes to make sure everyone goes and sees it. And that’s why I’m not sleeping, man,” says Koy with his trademark enthusiasm, despite a jam-packed schedule.

Joseph Glenn Herbert grew up in Washington state. His Air Force veteran father left the family when Koy was 10 and his mother raised the kids from there. The family moved to Las Vegas during his high school years and he began performing stand-up at open mics in 1989. (The stage name “Jo Koy” comes from a mishearing of his aunt calling him to dinner in Tagalog: “Jo ko, eat,” or “My Jo, eat!”)

Koy built a name in comedy through sheer will.

Cheer up at one of these spots for stand-up comedy in L.A.

In his early 20s, after being spotted by someone from the comedy club chain Catch a Rising Star, Koy became a regular support act for headliners and canvassed the streets, handing out two-for-one coupons. Attendance steadily improved.

Eventually, he realized people were coming to see him, not the headliners. He still couldn’t get those coveted top-of-the-bill spots, though, so he put his own money into renting a theater and persuaded local businesses to sponsor him, printing coupons for them on the backs of his tickets. Soon he found himself filling that house, then joined the Black College Comedy Tour and appeared on BET’s “ComicView” and “Showtime at the Apollo.” (“And I won it,” he says with pride.)

He moved to Los Angeles, where he worked as a stocker at Nordstrom Rack and Barnes & Noble and cleaned yachts to make ends meet for himself and his young son, Jo Jr. But breaking through in Hollywood was yet another long, slow grind.

“There was a lot of systemic racism going on. I know we throw this around a lot, but it’s true,” he said. “Late ’80s and ’90s, it was f— up. You can ask Cedric the Entertainer, Steve Harvey, Margaret Cho, anybody from that era. There was a division in comedy: It was literally called ‘White Nights,’ Friday and Saturday. If you were any other color, you had to do these theme nights — Thursdays were ‘Asian Invasion.’”

Now Koy can get onstage anytime he likes. It’s a hard-earned status he relishes as he strolls through the hallowed halls of the club that launched him in L.A., the venerable Laugh Factory. Up the stairs, in the most exclusive area, he teases employees: “Where’s my poster?” Everybody knows him here, just as when his friend, Tiffany Haddish, took him to a highfalutin party and he was stunned by all the big-namers glad-handing him.

“Everyone knows Jo Koy,” she says she told him, laughing at the memory.

He’s still getting used to who knows Jo Koy. After his 2019 Netflix special, “Jo Koy: Coming in Hot,” Amblin brought him in for a meeting.

“The minute we walked in, every other person’s walking up to me, ‘Oh my God, Steven cannot stop talking about your special,’ ‘Steven is a huge fan.’ I was like, ‘Are you talking about Steven from accounting?’ And they were like, ‘No, Steven Spielberg’s your biggest fan. He wants to make a movie with you.’ And I pitched ‘Easter Sunday’ to him.

“He’s been involved since the beginning, from the writing process to picking the director, casting, everything. Thank God for Steven Spielberg.”

“Easter Sunday” (directed by Jay Chandrasekhar and written by Ken Cheng and Kate Angelo) draws heavily from Koy’s life and stand-up routines.

“It was such a beautiful process to see bits that I do come to life,” said Koy. “From the balikbayan box to ‘You could have been a lawyer’ — all that stuff is just parts of my life, put into this film.”

The in-demand Haddish took a small role in the movie despite the two-week COVID-19 quarantine for the Canadian production. She says Koy appreciated her willingness to help but told her, “‘We can’t have you on lockdown for two weeks and then you only work for four days. It’s not worth it.’ And I was like, ‘My friendship is worth it.’”

Koy befriended Haddish when she was an up-and-comer at the Laugh Factory. “That’s my big brother, man. When I was homeless and he was basically a single dad, I would watch his son while he was onstage,” Haddish says. “We were both pretty poor, but I didn’t have no money. I was living in my car. He’d take me to this hot dog man across the street from the Laugh Factory. We got a hot dog wrapped in bacon. It was the best. He would give me two or three of them. Like, the best.”

Koy smiles at the memory, eyes glistening:

“Even when I didn’t have money, I got to share it. I feel like that’s a Filipino thing. I think I learned that from the balikbayan box. ‘I don’t have much either, but I got enough for us.’”

It’s no surprise, then, that the balikbayan box — the tradition of Filipino Americans sending care packages to the Philippines — is integral to “Easter Sunday.” “It’s more than just, ‘Oh, they come to this country and now they get to live the American Dream,’” he explains. “Now they’re making this money, and guess what? They have another family that they’re gonna support. ’Cause they’re not gonna leave them. I get emotional when I talk about that. ’Cause I remember filling those boxes up.

“My mom didn’t even have money. She’s filling up these boxes — I remember when there was no chocolate and I was like, we don’t even get chocolate — I remember she put in some Nestlé Quik. My mom and dad divorced and she put Nestlé Quik in there.”

He’s wiping his eyes now, but it’s not stopping the tears. “That’s the s— that she had to deal with and then to have that kid pull his eyes back on her and then she had to be all cool about it. And I had to sit there and watch my mom take it because that was normal.”

Koy had told the story onstage the night before, during an event with a host of other Asian comics at L.A.’s Rideback Ranch: When he was very young, Koy witnessed his mother stop to tell a young white child in a department store how handsome he was — and the boy responded by pulling back the skin by his eyes to mock her Asian identity. She had to turn to her son and tell him it was OK.

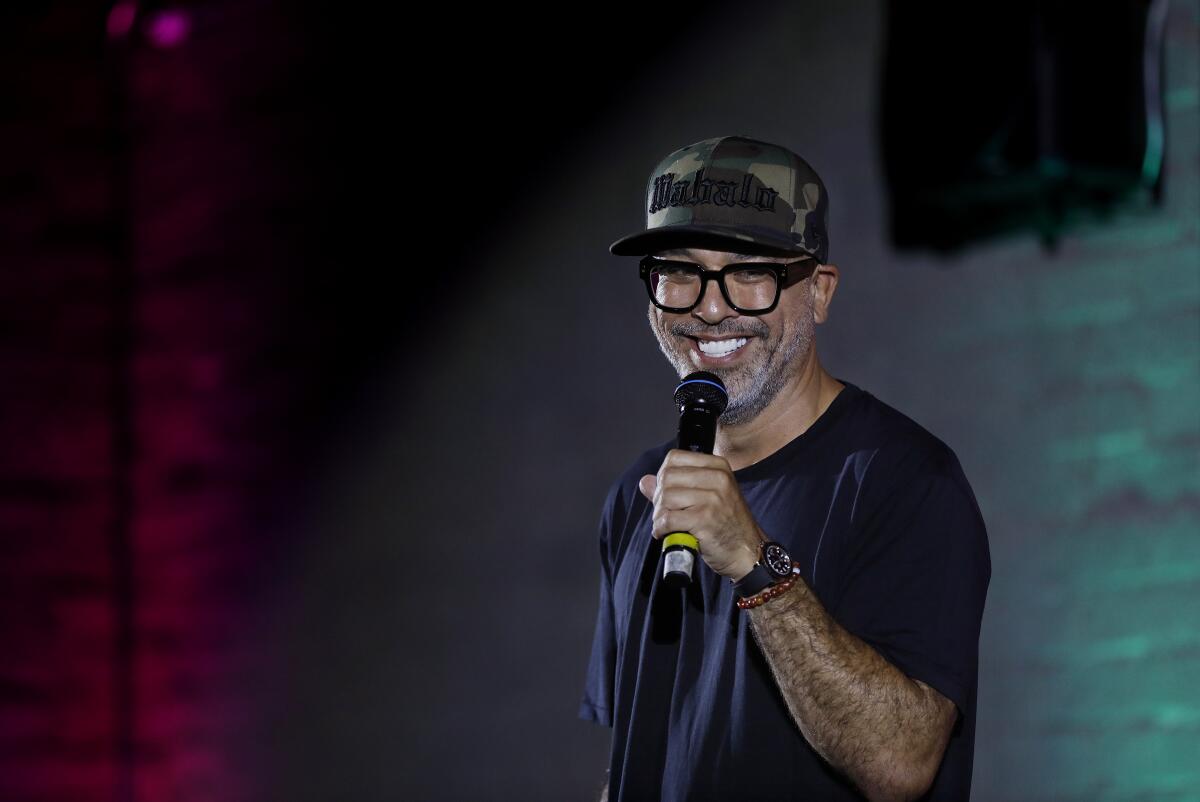

In person, Koy is an ebullient guy, a sincere hugger, even meeting you for the first time. He’s constantly telling people he works with that he loves them. But when he steps under the lights, he finds another gear. There’s swagger. He’s in his element. It happens in “Easter Sunday” too: He’s playing a character who’s put upon, balancing career and family, but when a microphone shows up in his hand, he suddenly owns the room.

Koy is adamantly opposed to the idea, held by many Hollywood gatekeepers he’s encountered, that his comedy is “too specific.” He understands comedy’s universal powers not only as a performer but as a fan. “Why was I able to relate to Eddie Murphy talking about his Aunt Bunny falling down the stairs?” he recalls. “I related to his mom disciplining the kids and having bionic ears. That’s my mom! That’s a Black woman I’m relating to, but my mom is Filipino. So why is it when it comes to me talking about my Filipino family, they’re like, ‘Hey, slow down... .’ Why, why? I don’t understand that note.

“There’s a reason why I’m selling out two arenas in every market. I am literally selling the same number of seats as the Golden State Warriors [at San Francisco’s Chase Center], if not more, because we added seats on the basketball floor. So to get 25,000 to 26,000 people to come see you tell jokes during the playoffs ... Come on, man. It’s not just Filipinos in there. It’s everybody in there.”

'Easter Sunday'

Rated: PG-13 for some strong language and suggestive references

Running time: 1 hour, 36 minutes

Playing: In wide release Aug. 5

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.