‘Licorice Pizza’ made Asians a ‘punchline.’ And the fallout is bigger than the Oscars

- Share via

Paul Thomas Anderson’s shaggy ’70s coming-of-age dramedy “Licorice Pizza” has garnered more than 125 award season accolades, including a BAFTA screenplay win and three nominations at this weekend’s 94th Academy Awards. But the film, which is up for best picture, director and original screenplay Oscars, has also faced accusations of anti-Asian racism due to a pair of scenes some have called harmful at worst and tone deaf at best.

The controversial vignettes unfold early on in Anderson’s rambling ode to the San Fernando Valley of his youth. Actor John Michael Higgins, playing Jerry Frick, the real-life owner of the Japanese restaurant the Mikado, speaks to his wife, Mioko (Yumi Mizui) — and later his second wife, Kimiko (Megumi Anjo) — in overly exaggerated Japanese-accented English. Defenders of the film counter that exposing Frick’s racism is the point. Its critics say his wives, two of the only nonwhite characters in the film, are robbed of agency and are themselves stereotypes that play into anti-Asian tropes.

Although interpretations of its intent vary, “Licorice Pizza” drew a small but vocal outcry as it rolled out in theaters and prompted articles in the Hollywood Reporter, The Atlantic and NBC. With few exceptions, Anderson and stars Cooper Hoffman and Alana Haim — who appear in the scenes as the main characters Gary and Alana, respectively — have largely ignored the controversy while promoting their film. (It likely helps that they have barely been asked about it.)

When Anderson has addressed it, his responses have been viewed as attempts to sidestep any concerns. In February, well into its Oscar campaign and after months of discourse, Indiewire’s Eric Kohn asked the filmmaker about complaints over the Frick character.

“It’s kind of like, ‘Huh?’ I don’t know if it’s a ‘Huh’ with a dot dot dot. It’s funny because it’s hard for me to relate to,” Anderson said. “I don’t know. I’m lost when it comes to that. To me, I’m not sure what they — you know, what is the problem? The problem is that he was an idiot saying stupid s—?”

To the suggestion that Frick’s racist accent, played to the rafters by Higgins, gives the audience permission to participate in his racism rather than condone it, he answered, “ ... that’s a possibility. I’m certainly capable of missing the mark, but on the other hand, I guess I’m not sure how to separate what my intentions were from how they landed.”

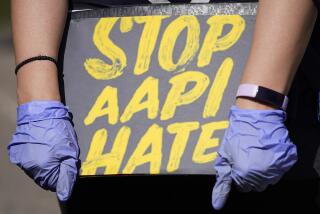

Amid a wave of hate crimes targeting Asians and especially Asian women in the U.S., Anderson’s failure to confront the criticism more forthrightly has been particularly deflating. “It’s frustrating,” says Michelle Sugihara, executive director of the Coalition of Asian Pacifics in Entertainment, which works to advance representations of Asian American and Pacific Islanders in Hollywood, “because it’s as if we’re invisible and our voices don’t matter.”

The longest tenured Asian American journalist on network TV has some stories of her own.

In the first scene in question, Gary watches his mother, Anita (Mary Elizabeth Ellis), present shallow ad copy for the Mikado to Frick and Mioko. Frick “translates” for Mioko in English, using an over-the-top mock Japanese accent; she responds to him in Japanese. Her words are not subtitled, suggesting that Anderson never meant for her to be understood by the other characters and a primarily English-speaking audience.

In the second, Gary mistakes Kimiko for Mioko, suggesting that he can’t tell the difference between the two women, an echo of the casualness with which Frick treats his Asian female partners as interchangeable and disposable. But the punchline comes when Alana asks Frick, who is speaking to Kimiko in the same offensive Asian accent, to translate — and he admits that he does not speak Japanese.

Frick’s fetishism of Japanese women may be intended as a cringe-inducing joke at his expense, but it falls flat for viewers who identify more with his wives than with Frick or the film’s protagonists. For some, the discomfort adds a provocative dimension to Anderson’s quasi-nostalgic love letter to the Valley. For others it feels like Anderson playing with explosive ideas but not sticking the landing, or pressing on a bruise with a bit out of step with the rest of the film.

Even with its 91% Rotten Tomatoes score, several critics flagged the Higgins scenes as clunky detours from the film’s otherwise sublime charms. “Strenuous comic nonsense,” Times critic Justin Chang wrote of the Frick character in his otherwise enthusiastic review.

Writing for Time, Stephanie Zacharek called the scenes “excesses that could have been excised,” writing that “Anderson can’t resist including not one but two scenes in which John Michael Higgins speaks loud mock Japanese, for alleged laughs — as if retro-mocking white boorishness of the past were in some way a corrective.”

Author and critic Walter Chaw put the insult more plainly: “At its worst, you’re reminded of how painful casual racism is when it’s used as a gag with not a point but a punchline.”

The debate comes only a few years after similar criticisms called out Quentin Tarantino‘s depiction of Bruce Lee in his L.A. valentine “Once Upon a Time ... in Hollywood.” When clips of “Licorice Pizza” went viral recently, Jenn Fang, founder of the Asian American feminist blog Reappropriate, watched social media flood with reactions to the scenes, in which stony expressions and reaction shots offer sparse clues as to Mioko and Kimiko’s interior lives.

“This scene is classic in terms of having an Asian American character serve as a plot device that is there to develop a white or non-Asian American character, rather than a character who is a full-fledged person in their own right,” said Fang, who has not seen the full film. Since the women‘s roles exist solely to make a point about Frick, she argues, Anderson’s film lands in a long lineage of problematic Hollywood stories.

“Especially in this moment where we’re dealing with the one year anniversary of the Atlanta spa shooting and this massive pattern of anti-Asian racial violence that has predominantly targeted Asian American women,” said Fang, “it is particularly heartbreaking for this scene to reinforce a long Hollywood history of Asian American women not being the subject of the story, but rather window dressing.”

Anderson was not made available for comment for this article. But his head-scratching responses to questions about the scenes have only added fuel to the flame.

Before the Indiewire interview, at the time of the film’s limited release last November, Anderson explained to the New York Times’ Kyle Buchanan that the scenes rang true to their 1973 setting and “it would be a mistake to tell a period film through the eyes of 2021.

“You can’t have a crystal ball, you have to be honest to that time. Not that it wouldn’t happen right now, by the way. My mother-in-law’s Japanese and my father-in-law is white, so seeing people speak English to her with a Japanese accent is something that happens all the time,” Anderson said, citing the stepmother of his wife, Maya Rudolph, Japanese jazz singer Kimiko Kasai. “I don’t think they even know they’re doing it.”

Film critic Ryan Swen, a contributor to Film Comment and the British Film Institute who writes at the website Taipei Mansions, offers a more positive assessment of Anderson’s intentions. He argues for reading the scenes, which “walk the finest tightrope,” closely for what is unsaid.

Watch Mioko’s face as Gary’s mom reads her stereotypical presentation out loud and “the expression on her face changes in this very pointed way,” said Swen. “I think that’s important.” Another clue as to what Anderson is attempting comes after the “I don’t speak Japanese” punch line, when Alana runs into a white waitress in Japanese garb in the Mikado ladies’ room, implying that Frick, and by extension his business practices, are more invested in superficial Orientalist aesthetics than authenticity.

These moments are clearly critiquing Frick, Swen added, but the bigger question is: “How do viewers feel about the film showing people engaging in Asian caricatures in order to critique them?”

There is such a thing as being too subtle in depicting racism without also depicting consequences or addressing it elsewhere in a film, argues sociologist Nancy Wang Yuen, author of “Reel Inequality: Hollywood Actors and Racism.”

“The argument is that those [offended] are just people who were not reading it right,” said Yuen. “But ... there’s no context. There’s no repercussions. There’s no discussion. You don’t even understand what the women are saying. They might be saying, ‘F— you,’ but we don’t even understand that. It’s too subtle for people to say, ‘Oh, well, he’s racist and it’s terrible, and that’s what’s happening in this scene.’”

Several Asian American moviegoers have shared experiences of going to see “Licorice Pizza” in a theater and hearing strangers laugh at Frick’s antics.

“Picture this: You’re watching ‘Licorice Pizza.’ It’s brilliant,” tweeted podcaster Dave Chen. “Then, early on, a buffoonish character drops an Asian caricature. The (mostly white) audience laughs. And now, you gotta think about that laughter the rest of the film. Did you picture it? Because it f— sucks.”

A 2021 study by CAPE, Gold House and the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media found that Asian and Pacific Islander characters served as a comedic punch line in 43.4% of Hollywood films from 2017 to 2020. More than a third of characters (35.2%) fell into stereotypes such as the “Forever Foreigner,” “The Lotus Blossom” and the “Dragon Lady.”

According to Stop AAPI Hate, between March 2020 and December 2021, a total of 10,905 hate incidents against Asian American and Pacific Islanders were reported, 69.8% of which were directed at women. The majority of reports (66.9%) were incidents of harassment.

In 2020, the year “Licorice Pizza” was filmed, anti-Asian hate crimes in Los Angeles increased by 76%, according to the L.A. County Commission on Human Relations, as well as nationwide, per the FBI. Preliminary data shows that anti-Asian hate crime in major U.S. cities skyrocketed by 260.5% in 2021, according to Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism‘s director, professor Brian Levin, and an ongoing wave of shocking anti-Asian violence across the country has many in the AAPI community in fear.

A December statement from Media Action Network for Asian Americans, which urged Academy voters and other groups to not nominate the film for awards, slammed the “Licorice Pizza” scenes as existing “simply for cheap laughs.” “What people subconsciously get is the behavior, not the intent,” a MANAA spokesperson said. “And that subconsciously can lead to a dehumanization of a race.”

Given how much content consumed worldwide is created in Hollywood, said Sugihara, the creative industry has an opportunity and a responsibility to more deeply consider its impact. “What we watch on our screens affects how we feel and act, not only about others but about ourselves,” said Sugihara.

It’s important to distinguish between intention and impact, Sugihara says. “If you’re saying it’s a scene about racism or essentially a teachable moment within the confines of entertainment, but you still don’t unpack it, you can’t say ‘that’s racist’ without at least an acknowledgment that this is really the intent.”

One Asian American Oscar voter, who asked not to be identified due to the sensitive nature of the topic, said he did like “Licorice Pizza” and hadn’t taken issue with the “cringey” Frick character. The “white buffoon” was a reminder of many instances of exoticizing racism he’d directly experienced himself. This voter had even witnessed one such incident occur recently on the awards circuit to a female filmmaker of color currently nominated for an Oscar.

Higgins “wasn’t Mickey Rooney in ‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s,’” the voter said, comparing it to arguably the most egregious yellowface caricature in Hollywood history.

But seeing how Anderson responded to complaints about the scenes made the voter reconsider supporting the film, and it subsequently dropped way down his Oscar ballot. “PTA,” this voter said, “should be more transparent about why he had that character in there.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.