- Share via

“Spain has a bad a relationship with its past,” Pedro Almodóvar said during a recent visit to Los Angeles. “Spanish people don’t like to be told about the darkest parts of their history.”

Beloved internationally for his exuberant melodramas, often laden with sizzling eroticism, Almodóvar has consistently transgressed conventions of gender and religious dogma without overt political statements — especially not about the Franco regime of his early years. The choice to avoid dealing with that period head on in his work was deliberate.

But his latest dramatic confection, “Parallel Mothers,” which is now playing in limited release following a world premiere at the Venice Film Festival, explicitly honors the thousands of victims of the late 1930s Spanish Civil War and its aftermath, in which the murderous dictator seized power until 1975.

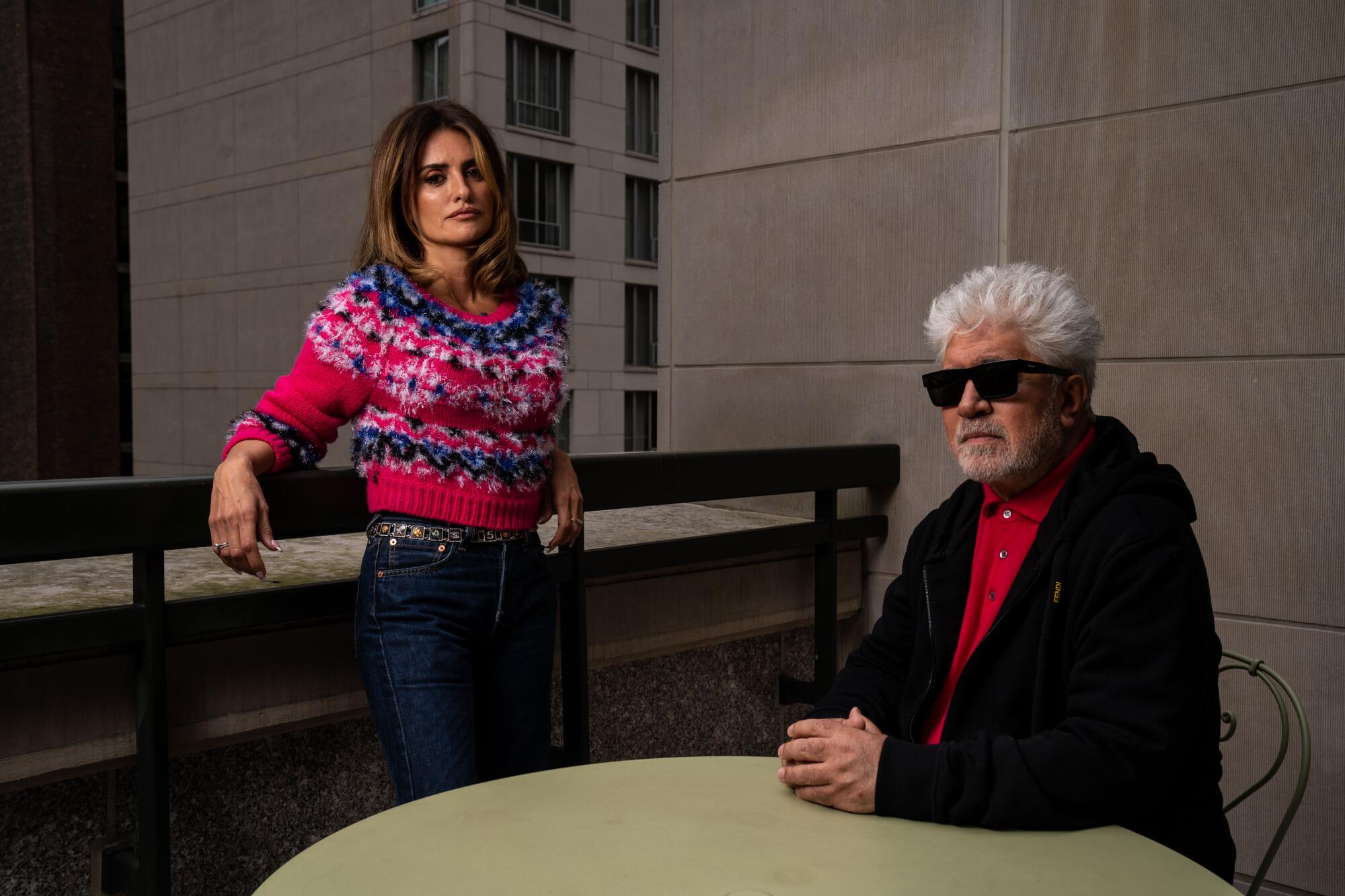

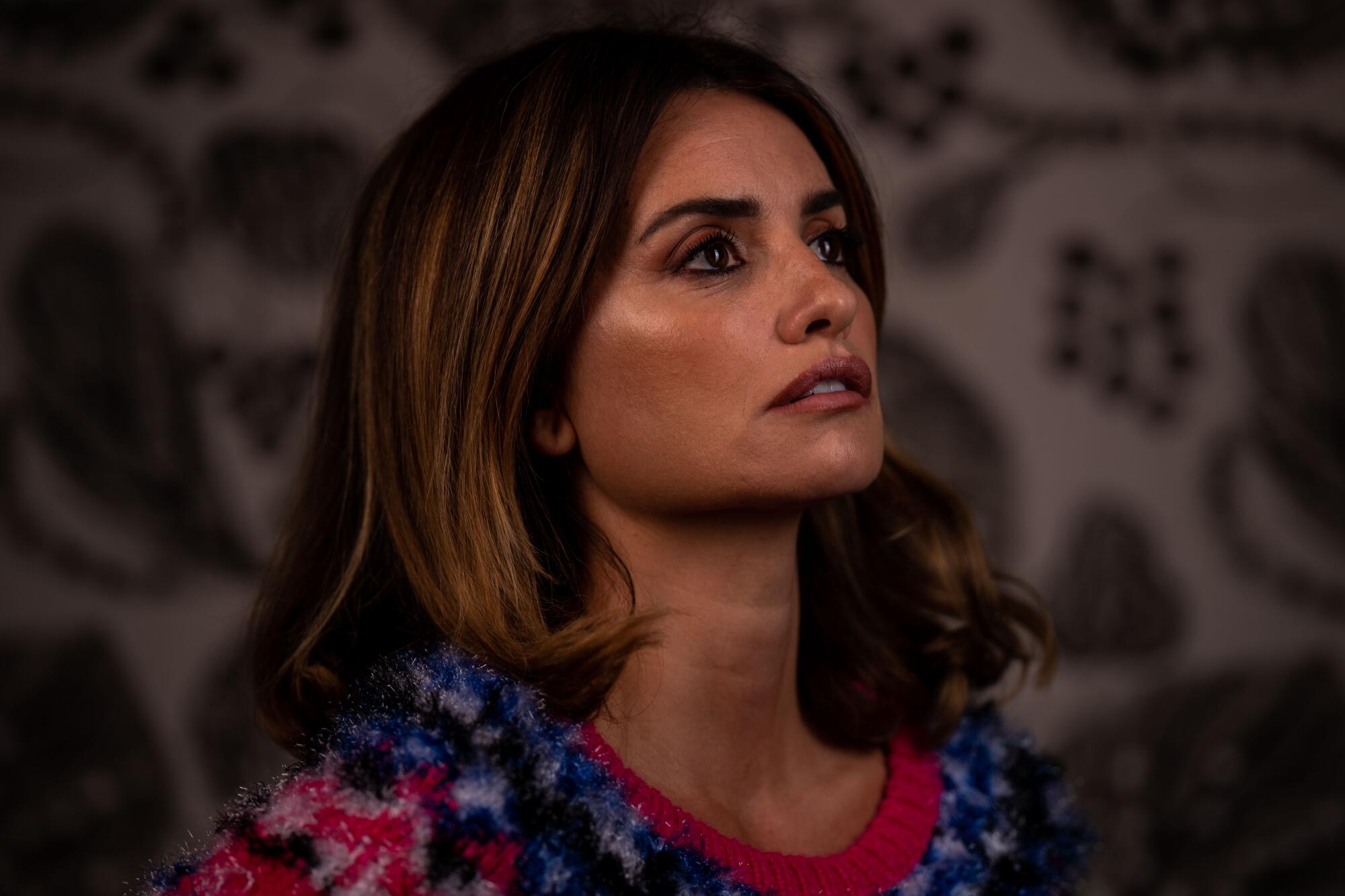

Oscar-winner Penélope Cruz, Almodóvar’s longtime muse, stars as Janis, a photographer who befriends a younger woman, Ana (a fresh-faced Milena Smit), when they both give birth to their respective daughters in the same hospital. As entanglements of the heart ensue, Janis also tries to orchestrate the exhumation of mass graves — horrific byproduct of the armed conflict — in her family’s rural hometown.

Penélope Cruz gives one of her finest performances in Pedro Almodóvar’s first movie to directly confront the horrific legacy of the Spanish Civil War.

Throughout the dictatorship and for many years after, Almodóvar recalls, people in Spain buried their memories of the atrocities over concerns about retaliation for speaking out.

“My father went to war when he was 18. He wasn’t a Republican, but they took him to fight. At home, he never said a single word about the war,” he said. “Most families had a pathological fear that something could happen to their children or grandchildren.”

Cruz, speaking over video call, shared that her family never learned exactly what happened to one of her great-grandfathers, yet, as it was customary, they didn’t much dare pry.

“There are so many mysteries about that topic in many families. There are many people who still don’t know what happened,” she said. “If you ask your grandmother about your grandfather or a great-grandfather and she says, ‘I don’t know what happened,’ you can’t push much further for information because it’s a very delicate and traumatic subject.”

By the same token, Spanish cinema at large has been reluctant to engage with that tenebrous period. Of the few titles that exist, Almodóvar considers the two by Victor Erize, “The Spirit of the Beehive” (1973) and “El Sur” (1983), the most notable to date.

But now, as the country appears more willing to discuss the truth, “Parallel Mothers” has entered the conversation. Since its release at home, Almodóvar has received numerous letters from family members asking whether some of the cases depicted in the film (like that of a man buried with a glass eye) were inspired by their loved ones’ final moments. And they could be, since every detail in the film about the disappeared came from documented sources.

Earlier this year, the Spanish Socialist party introduced the Law of Democratic Memory, finally allocating institutional support and financial resources to unearth the remains still in unmarked graves across the country and to identify those in a relatively good state.

Prior to this pivotal initiative, forensic anthropologists volunteered time to conduct sporadic excavations, as Janis fights for in “Parallel Mothers.”

“[The argument] against the exhumations is that they would open old wounds,” Almodóvar said. “But I’ve spoken to a lot of the families and all they want is to have a place with the name of their family member where they can take flowers. It’s something basic to which every human being has a right. “

Although the conflict might seem distant, Almodóvar believes understanding the history has gained new relevance as an ultra-right party has gained ground in Spain over the last few years. In what the director describes as the pinnacle of fake news, they push a revisionist agenda retelling Spanish history according to Francoist values.

Within the context of how seldom the Spanish Civil War has been tackled in local productions, Almodóvar finds it curious that Mexican director Guillermo del Toro has made two acclaimed films set against its backdrop: “The Devil’s Backbone” and “Pan’s Labyrinth.”

Almodóvar produced the former, a ghost story set in an orphanage, through his company El Deseo, helping the master of monsters navigate Spanish culture. He is impressed at how Del Toro has managed to survive within the Hollywood system while preserving his artistic integrity. The two have fostered a friendship based on mutual admiration.

“He is so affectionate and is always celebrating my work,” said Almodóvar. “Every time we see each other he tells me that he still wants to make a third movie about the Spanish Civil War with us. And I tell him, ‘Guillermo, whenever you want to do it, we are there for you.’”

Revisiting the past has always been integral part of Almodóvar’s process. And some screenplays require longer gestation periods — he first talked to Cruz about “Parallel Mothers” about two decades ago. By the time they shot “Broken Embraces” in the late ‘00s, he had a treatment. (A poster for “Parallel Mothers” can actually be spotted in that film. “In my movies there are many characters who are film directors or writers, so I like to sneak in titles that are already mine legally or that I have something written for,” he explained about the Easter egg.) In the years since, Cruz repeatedly inquired about the story.

Fast-forward to the COVID-19 lockdown of 2020, which lasted three months in Spain, when Almodóvar returned to the screenplay. During that fruitful period in isolation, he finished the story and started shooting almost immediately. To avoid having characters wearing masks on screens, and explain why, he decided to end his fiction in 2019.

“Parallel Mothers” is Almodóvar and Cruz’s seventh collaboration (eight if counting her cameo in the raunchy airplane comedy “I’m So Excited”). In all of them but one, Cruz has played mothers in distress.

“Penélope has a blind faith in me,” said Almodóvar. “She has more faith in me than I have in myself.” Since he first saw her film debut “Jamón Jamón,” Almodóvar sensed Cruz was an atypical actress, and on the flip side, a burgeoning Cruz knew she wanted to pursue the dramatic arts immediately after watching “Tie Me Up, Tie Me Down” as a teenager. When the director first cast her in “Live Flesh,” for a memorable part of about eight minutes, her earnest dream of working with him was fulfilled.

It had been a few years since the pair’s last collaboration, and Cruz was ecstatic to receive a call from her favorite director amid the uncertainty of the pandemic. “It was a joy to know that he was writing it and that we were going to make this together,” she said. To portray Janis, Almodóvar asked her to undergo the longest and most arduous rehearsal period he’s ever done (about three months), in part to help her novice co-star, Smit.

The interpersonal dynamic between Cruz’s Janis and Smit’s Ana presents a new example of the open families that have been a staple in Almodóvar’s oeuvre, dating back to “Law of Desire.” But Janis was born of Almodóvar’s admiration for women’s hard-earned freedoms in the 21st century. “Today, a woman who wants to be a mother doesn’t need to be married. She doesn’t even need to have sexual intercourse to become a mother,” he said.

That something so intrinsically feminine as motherhood is feasible for women without men being indispensable strikes the storyteller as a triumph of our time. “This is the most feminist character I’ve written considering that all of them are feminists. I’ve given all my female characters an enormous moral autonomy,” said Almodóvar.

“He has written some of the most incredible characters for women in the history of cinema, and that message of respect and equality has always been there,” noted Cruz. “I’ve played other women for Pedro who were also feminists in their own way. Even the woman in ‘Volver’ or Sister Rosa in ‘All About My Mother’ are characters with a very open mind, perhaps in different ways but they are all fighting for the same thing.”

Almodóvar believes the character of Janis was uniquely complex for Cruz because she had never experienced the feeling of guilt and shame that comes with keeping a secret. “Janis [is] always aware of what she says and what she does. There’s always a contradiction within her,” explained the director.

“My relationship with my own feeling is distinct from that of Janis. It’s much easier for me to express myself, easier for me to cry,” said Cruz. “I’m much more transparent than she is in that sense.”

For her wrenching rendition, Cruz won the best actress award at the 2021 Venice Film Festival and more recently the same prize from the Los Angeles Film Critics Assn.

While pondering mothers, Almodóvar returns to the motherland and laments how Spanish conservatives, in a similar fashion to what’s happened in the United States, have co-opted patriotism.

“The right wing has stolen our flag. In Spain if someone wears the flag in their clothing, or their hat, or their watch you know that person has far-right ideas,” says Almodóvar. “They have stolen our national symbols and equated them with their ideologies.”

What he recognizes as his place of origin isn’t tied to political affiliations but to the words that give a voice to him those who raised him. As such, it can’t be taken away.

“The Spanish language is my homeland,” said Almodóvar. “And my homeland is also those yards in La Mancha full of women working and talking about everything that happened on our street. That street is for me like the place about which Gabo [Gabriel García Márquez] wrote ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude.’”

Los Angeles Times film critic Justin Chang’s best movies of 2021 include ‘Drive My Car,’ ‘The Power of the Dog’ and ‘The Green Knight.’

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.