- Share via

The divers who saved 12 boys and their soccer coach from a flooded Thailand cave in 2018 were obviously brave. Immense courage would be required from anyone willing to swim over a mile through sediment-rich water in complete darkness, expecting to bump into 13 dead bodies. But the men who volunteered to fly to Asia from their homes in Australia, England and Ireland to help with the rescue also shared some more unexpected character traits.

“They were pretty ornery right off the bat,” said E. Chai Vasarhelyi, who interviewed the cave divers for the new documentary “The Rescue.” “They all kind of self-present as misfits — as people who had a hard time fitting in. They feel most comfortable in a muddy hole but ended up being the most unlikely heroes.”

The filmmaker, along with her co-director, husband Jimmy Chin, are no strangers to “weird, nerdy characters. That’s kind of our thing,” laughs Vasarhelyi. She’s referring to the last film she and Chin made: “Free Solo,” which won the documentary feature Oscar in 2019. The film centered on Alex Honnold, a world-renowned athlete who was attempting to scale Yosemite’s 3,000-foot El Capitan rock wall using only his hands and feet. While the film was ostensibly about Honnold’s climbing feat, much of its emphasis was also on his clinical, fearless and sometimes abrasive personality.

But the divers?

“They make Alex look normal,” jokes Vasarhelyi.

The directors began working on “The Rescue” in 2019, after filmmaker Kevin Macdonald had to drop out of the project to focus on his legal drama “The Mauritanian.” Macdonald had already began interviewing the divers who participated in the Thai effort, deciding to focus on their stories in part because Netflix owned the rights to the children’s stories. National Geographic had made a deal to share the divers’ accounts. The company released “The Rescue” in theaters last week to a pandemic record limited release average and is expanding nationwide this week ahead of a Disney+ streaming debut in December.

Chin, who is himself an accomplished climber with a North Face sponsorship, immediately felt a kinship to the divers despite their differing disciplines.

“Big wall, high-altitude climbing only draws pretty specific people and personality types, and so does cave diving because it’s a specific discipline with such high stakes,” he said. “The problem-solving, the ingenuity required, the amount of risk assessment — those aspects make it really appealing to a certain mind-set. You have to make perfect calculations because if you don’t, you die.”

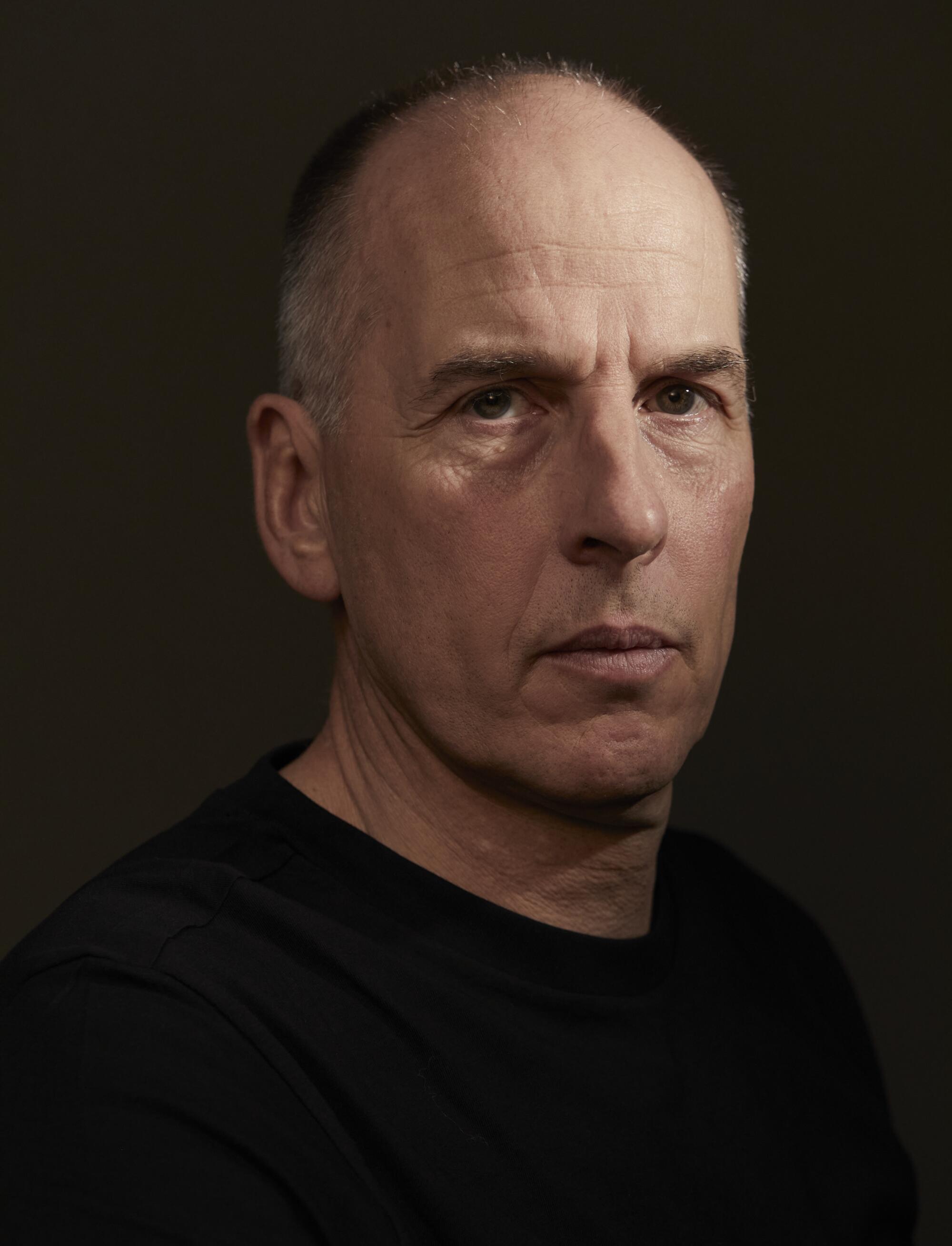

While Chin and Vasarhelyi interviewed dozens of people involved in the international rescue — Thai Navy SEALS, members of the U.S. Air Force, local volunteers — their focus ended up largely on three men: Rick Stanton, 60, John Volanthen, 50, and Dr. Richard “Harry” Harris, 57. All did cave diving as a hobby, and yet due to the uncommon nature of the sport, were called upon for their expertise in Thailand.

Stanton, a retired firefighter, and Volanthen, an IT consultant, were two Brits who’d known each other for decades and often went diving together. Harris worked as an anesthesiologist in Adelaide, South Australia, and was called upon to figure out the proper concoction of sedatives to give the stranded soccer team before the attempted rescue. The Times interviewed the trio separately over video chat from their respective homes.

Were you surprised that the filmmakers picked up on commonalities in your personalities?

Stanton: We could see that coming before we even started. I guess that’s why we all turned to the same hobby when we were late teenagers and we all get on. We’re introverted, I guess.

Harris: That’s well-recognized within our group around the world, almost. John said “we don’t play well with others.” I don’t mean that in an antisocial way, but I think there’s a bit of truth to that. I don’t know any cave divers who were successful in team sports. And I’m definitely that way. I was more interested in individual pursuits like being in the ocean and being in the bush and camping, that sort of stuff. There’s also a very common thread with motorcycles in the cave divers. Just about all of them have had high-powered motorcycles and have later sold them because they were concerned about killing themselves.

Volanthen: I hope we don’t come across as too odd. But perhaps we are a strange bunch with a strange hobby. We’re all quite determined. It does require a certain kind of person who is able to get knocked down, get back up again and carry on. And also perhaps to be prepared to suffer a certain level of discomfort that many would choose not to.

Do you find any similarities between your jobs and cave diving?

Volanthen: I’m in IT — a network engineer by profession. I think that risk assessment, that ability to look at a situation when things are going wrong and to make unemotional and hopefully correct decisions without panicking in sort of a linear, sensible manner — I think the two are very complementary.

Stanton: The bread and butter of firefighting is rescuing people — going into a house where you can’t see anything that you’ve never been in, trying to find somebody and rescue them. Going into dark places and finding your way around, really.

There’s a moment in the film where the Thai Navy SEALS grow frustrated that they’re unable to cave dive as well as three men over 50. What makes someone a good cave diver?

Harris: Most people, including very expert divers, do not go out of their way to immerse themselves in small, dark tunnels with no visibility and kind of enjoy that feeling of problem-solving and groveling around in the dark to work out where you’re going. That’s challenging and usually enjoyable for us. The Thai Navy SEALS are the obvious example of people who are courageous, competent, fit, well-trained — but they hadn’t specifically trained in that environment. Equally, asking us to do some of the stuff that they do, we would be all at sea as well. If you trained those guys to do cave diving, they’d probably be better at it than us, but it was just not possible in the time available so you had to get people who already had that background and experience to do the job.

Stanton: The main thing about cave diving is that it isn’t only a physical activity, it’s a mental activity. And you’ve got to be very technical and practical with all the equipment. You also have to have the right temperament where you don’t get flustered.

Volanthen: My interest is in problem-solving. I’m a whitewater kayaker as well, and it’s those sorts of experiences that feed into being able to read a cave, look at a set of water, and be able to manage myself in a certain environment. Also, we’re quite relaxed in the water so we don’t particularly breathe very hard.

Dr. Harris, you gave the soccer team an injection of sedatives to relax them so that they wouldn’t panic while they were being dived out of the cave. How did you decide on that combination of drugs?

Harris: There is only one drug that fits the bill in this situation, and it was fairly obvious to me as soon as I started to think about the problem that ketamine would be the answer. It’s got a number of pharmacological properties and clinical properties that make it suitable for this task. These kids had to keep breathing by themselves. We couldn’t artificially ventilate them. So any drug that depressed their respiration significantly was going to be a nonstarter. And ketamine is very good at allowing people to breathe normally.

It also leaves a little bit of airway protection, so that if you lie on your back and a bit of saliva dribbles down onto your larynx, that would make you cough and spit it out — you retain a little bit of that protection with ketamine. My greatest fear was that those masks were going to fill with water or even that the boys would drown in their own saliva, so any airway reflexes that were still intact would work in their favor.

Ketamine is also pretty good at providing a pretty stable blood pressure and cardiovascular system. You might ask with all these fabulous properties, why don’t we use it routinely for anesthesia? The problem is, it has some horrible side effects and that horrible feeling of nightmares and bad trips and things, which anyone who has taken it in a nightclub will be able to share with you. It’s not a great drug for someone coming in for their knee arthroscopy where they’re completely fit and healthy and there are much better options where we don’t have all those unpleasant side effects.

How is it possible to remain calm in a completely dark, unknown environment like that?

Stanton: I’ve always been unfazed by being underwater in a cave. Quite relaxed.

Volanthen: I’m a great believer in visualization. I visualize my emotions in my mind and I put them in a box on a shelf to the high and the right. I leave them there for the duration of whatever it is that I have to do. In that way, I’m able to look at a problem unemotionally. But I do make a point after that event of taking that box off the shelf and peeking into it just to see if there’s anything in there that I might need to deal with. And happily in this case, there wasn’t because we were so successful.

When people are perplexed by your hobby, how do you explain to them why you like it?

Volanthen: Cave diving quite often is seen to encompass most people’s worst fears of being in the dark, being in small spaces, being unable to breathe. So I completely get why people would think it’s a foolish hobby or something they wouldn’t like to try themselves. But equally, I really enjoy the challenge, and it’s a privilege to be able to go to places that have never seen light before, let alone a human footprint. I’m the first person to go there not this week, not this month, but ever. That’s a huge privilege and a huge responsibility.

Stanton: Exploration. There’s not many places in the world to explore now — you can go to the deepest oceans or unclimbed mountains in the middle of nowhere. And the whole surface of the earth has been photographed anyway. But the fact that you could go exploring on a tiny island like Britain was really fascinating to me.

The directors suggested the experience of participating in the rescue helped you self-actualize. Do you think that’s true?

Stanton: Look, everyone is very accomplished in their own field, aren’t they? Harry’s a very successful anesthetist and emergency doctor. He might not have been very good at team sports in school, but that’s not everything in life. I’m sure that he was very confident in himself before the rescue, as all of us were. Otherwise, we wouldn’t have had the confidence to do the rescue. We’ve all developed into being successful and confident adults before Thailand, or we wouldn’t have had the wisdom or the abilities to go in and do what we did, liaise with government ministers and force them to approve our plan.

Volanthen: I feel I’m quite exceptionally grounded. I have no delusions of grandeur. I don’t view myself any differently. I think each of us is only as good as what we’re doing now. That rescue is really very much in the past. It’s been brought into the present with the film. But that doesn’t mean we are special just because Jimmy and Chai have managed to capture a sense of what happened.

Harris: I don’t think it’s changed me at all, really. And it certainly hasn’t changed the way I look at the world in terms of the need to challenge yourself and take risks and do stuff that is difficult and sometimes dangerous to make yourself a stronger, more resilient person.

None of you were paid to partake in the rescue. Why take on the risk?

Volanthen: This isn’t my or our first rescue by a long stretch — we’ve been involved in a number of rescues and a number of body recoveries as well. It seems to me it’s the right thing to do to offer help to your community when someone is in need. It’s the same as giving blood. I give blood regularly. But on top of that, I think this was a very specific technical problem which we knew we were very well suited to. I felt very strongly — and I appreciate this sounds arrogant — we knew we had a set of expertise that was perhaps uncommon and that we felt we could make a difference.

Harris: I was convinced that none of these children would survive and I was going to be the agent of their death. I felt like I was euthanizing them. The only reason I agreed to do that was because the alternative seemed even worse — they would be left to die a very dreadful death over several weeks in the cave. And I just felt like, “Well, I can’t walk away from that even if there’s a one in a million chance that one of those kids will come out alive. Either they die in their sleep under anesthesia or they die this grotesque death with the fear and the psychological torture that that would involve.” I felt like the risk was on us in terms of how that would affect us, how that would affect my career — you can imagine the trial by media and social media if I became the Dr. Death of Thailand. But again, what are you gonna do? Are you gonna just run away and leave them, or give it a go?

What are you hoping audiences take away from the documentary?

Stanton: We wanted to get our story across, because most people can’t imagine what it’s like to be in a cave. In many ways, we made it look a bit too easy, because every day we went in and every day four or five kids came out. Nobody knew how technical and dangerous it was and how close things actually got for the boys. And people don’t understand how emotionally attached you were to the boys.

Volanthen: One of the things I hope that people learn is that we’re capable of amazing things when we work together. And also as individuals, if we believe in ourselves and go forward when we don’t think we can, we’re each capable of amazing things too. If it’s possible for some people to take that away from the film, then in my view it will have done a very useful and very important job.

Harris: The main reason it’s so powerful is because of the sense of community. All of these countries came together in a high-stakes mission to save some children they’d never heard of or met. People were willing to put their lives at risk to do that. When has it been more important for the global community to band together with all this stuff going on? I’m so frustrated about the First World problems that we are talking about at the moment around COVID and vaccinations. People who are being so selfish around their personal needs.

You look at countries like India and Indonesia and Thailand who are doing so tough with the pandemic and dying in droves. And people are going, “Oh, I don’t want the Pfizer, I want the Moderna” and being fussy and difficult about it. I just think, for goodness skates, get a grip. This sort of film and this sort of story will hopefully snap people out of that a bit and remind them there are bigger things at stake and we can behave much better as a global community.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.