What went wrong with the ‘Sopranos’ prequel: Our experts break it down

- Share via

Fourteen years after TV’s most celebrated — and debated — cut to black, series creator David Chase returned to “The Sopranos” saga with a feature film prequel, “The Many Saints of Newark.”

The film — which was released in theaters this past weekend and also started streaming on HBO Max, as every other 2021 Warner Bros. title has — proved to be a commercial disappointment that brought in just $4.7 million at the box office and earned a crippling C+ CinemaScore from opening weekend audiences.

But it has also given us much to reflect on — from the legacy of one of TV’s “greatest shows of all time” to the barely tangible divide between the cinema and the “small screen.” Was “Many Saints” a mistake, misunderstood or something in between? Here, three Times staffers break it all down.

Matt Brennan, TV editor: I certainly didn’t dislike “The Many Saints of Newark.” In fact, I had a blast creating diptychs in my head of “Sopranos” characters with their younger selves: Paulie Walnuts (Tony Sirico/Billy Magnussen), Junior Soprano (Dominic Chianese/Corey Stoll), Livia Soprano (Nancy Marchand/Vera Farmiga) and, of course, Tony himself, played by the inimitable James Gandolfini in the original and his son, Michael, here. But I must admit I am baffled by it.

David Chase’s crime drama, which ran on HBO from 1999 to 2007 and is generally considered to have ushered in “the Golden Age of television,” rarely went in for fan service. The series famously ended with a cut to black that had desperate viewers frantically calling the cable company, suffused with ambiguities that are still being debated more than a decade later: Was Tony killed? What about Carmela, A.J., Meadow? And if she survived, did Meadow ever learn to park? And yet the very existence of “Many Saints” feels like fan service, an attempt to scratch an itch that, as Willy Staley recently pointed out in the New York Times, can easily be remedied by watching, or rewatching, “The Sopranos.”

Ultimately, I am left with more questions than answers, because “Many Saints” does not, in my view, substantially deepen our understanding of Tony Soprano, the DiMeo crime family, or the rise and decline of the Mafia concern we call the United States of America. Would this have worked better as a miniseries? Why does Chase, one of its preeminent artists, seem to have turned up his nose at TV? And how can he justify sullying a series bookended by one of the best pilots and best finales in TV history with an appendage like this?

I’m reminded of what Tony says to Dr. Melfi (Lorraine Bracco) in the series premiere of “The Sopranos”: “I feel like I came in at the end. The best is over.”

Mary McNamara, culture columnist: I have to confess that I was not thrilled when the existence of a “Sopranos” prequel was announced. Though I was a fan of the show when it aired and still admire it deeply, I did not feel the need for an extension of its “universe.” Indeed, I find the notion of a “Sopranos universe” wildly alarming — will Venom be part of it? Is a cross-over with “Mad Men” in the works?

The wonder of the series was its unwavering specificity, its passionate and monogamous devotion to its main characters, brought to life by an unparalleled cast, and their world. Like Stephen King, Chase was a master of conjuring a state of resonate normalcy so unassailable that even the most violent, psychotic actions made sense. I didn’t need to know how Tony became Tony — one look at Marchand’s Livia and Chianese’s Junior made that pretty clear. So I am not the audience for whom this film was built. I watched it out of curiosity and, perhaps, a sense duty, but my expectations were low.

The ‘Sopranos’ prequel film resolves a long-standing debate among fans about what happened to a key character, but it may not be who you think.

Not low enough, as it turned out. From the opening moments, careening through a graveyard as poor dead Christopher Moltisanti (Michael Imperoli) offers a brief, baffling and unhelpful narration, I was a stranger in a strange land. “Many Saints” was not just unrecognizable as a prequel, it was very confusing as a film. “Wait, who is that?” quickly became the mantra of my familial viewing party, not just in an effort to identify the younger iterations of familiar characters, but to try to figure out what the hell was going on.

The child Tony (William Ludwig) was helpfully pointed out by Christopher’s voice-over, and Farmiga’s Livia was instantly recognizable when she dangled a lit cigarette over a baby carriage, but who were the rest of these people and what, exactly were they doing? Numbers were being run, the Italians were clashing with Black gangsters who, like the rest of their Newark community, were in revolt, but what exactly was the relationship between Tony’s father, Johnny (Jon Bernthal) and his “uncle” Dickie Moltisanti (Alessandro Nivola)? What position did Dickie’s father “Hollywood Dick” (Ray Liotta, in one of two roles) hold in the family business?

Part of the fun of any mob narrative is assembling the hierarchy of power, but in “Many Saints” the pieces of that jigsaw remain sprawled on the table. Who did Johnny, Dickie and all the guys answer to? And was I supposed to know that going in?

For reasons known only to David Chase, Dickie is the center of “Many Saints.” In Dickie’s continual (and frankly absurd) struggle to strive for good while viciously murdering people (often in scenes narratively jerry-rigged for just this purpose), I suppose we are meant to see a template for Tony’s similar struggle. But who is this guy anyway? And why did he not come up more in Tony’s endless therapy sessions? As hard as Nivola works, it is hard to see Dickie as anything but a brutal bastard, and even more difficult to see why Tony would hero-worship him if the script did not require it.

But maybe I am missing something. Justin, help a girl out.

Justin Chang, film critic: I’m afraid I must echo the general bafflement, Mary, though not necessarily for the same reasons. My wife and I actually kind of enjoyed playing “Spot the Young’un” and congratulating ourselves on correctly identifying Little Big Pussy and junior Junior (admittedly not the hardest task, given how well Stoll nails Chianese’s dyspeptic scowl). And I, for one, would gladly watch the feature-length origin story of Silvio’s hair.

The one guy who doesn’t make you ask “Wait, who is that?,” of course, is Tony Soprano himself, given the downright eerie resemblance between Gandolfinis padre e figlio. But that makes it all the more frustrating that Tony doesn’t occupy the movie’s center of gravity. I’m not sure I needed to know how Tony became Tony, either, but it seems almost perverse to introduce such an ideal younger stand-in and not give him anything more interesting or revealing to do than rob an ice-cream truck. Tony was always the most dazzling star in “The Sopranos’” galaxy, of course, but Chase’s show was rich and expansive and (needless to say) long enough to contain him and dozens of other memorable characters, all of whom were compelling through their associations with him but also in their own right.

“The Many Saints of Newark” never finds that balance. I have to say that if I was anticipating this movie for any reason, it was to see how it would handle the character of Livia, given how crucial and destructive she is to Tony’s psychological development: She’s still the most indelible of the show’s many monsters. And what an opportunity, too, to revive a character whose fictional life was cut short by Marchand’s untimely death in 2000. Stepping into Marchand’s shoes would be a challenge for any actor, but Farmiga — who notably inhabited an even more iconic psycho mom’s backstory in “Bates Motel” — is as up to the challenge as anyone. (Her rendition of Livia’s “Aaaaawwwww, poooooooor yooouuuuuu!” is a particular hoot.)

Can the prequel film ‘The Many Saints of Newark’ kick off a new era in the ‘Sopranos’ saga?

The movie leaps to life in Livia and Tony’s too-few scenes together. By contrast, as Mary notes, the allegedly formative relationship between Tony and Dickie never comes into satisfying focus, to the point where Dickie’s entire story feels like the stretchiest of retconned narratives. None of which is the fault of Nivola, who’s been a terrific, under-appreciated actor for decades (check out his superb recent work in “Disobedience” and “The Art of Self-Defense”), and who’s long deserved to carry a movie of his own.

But it would have to be a more coherent, less overstuffed movie than this one. It’s hard not to agree with Matt’s suggestion that this material would have worked better as a miniseries — or to simply rubber-stamp our colleague Lorraine Ali’s conclusion that “The Many Saints of Newark” “might have played better as a limited series rather than a truncated self-contained production.” It doesn’t help that the movie was released simultaneously in theaters and on HBO Max, which is hardly the filmmakers’ fault or responsibility; still, having it sit there, side-by-side with every superior episode of “The Sopranos,” throws the discrepancy into very harsh relief. The movie’s most thrilling moment is also its most deflating, when you hear that familiar blast of “Woke Up This Morning” over the closing credits: It’s a rousing callback to the series, and it takes all of five seconds for you to realize just how unearned it is.

Brennan: To take Justin’s point one step further, “Many Saints” feels like a marker of how rapidly we now process beloved cultural artifacts into new “content” to feed the streaming beast (see also: Netflix’s dreadful “Breaking Bad” sequel “El Camino”), all at the the risk of setting the prequel/sequel/remake up for failure, or even devaluing the original.

But to apply Occam’s Razor to the question of what went wrong with “The Many Saints of Newark,” I wonder if the answer is even more fundamental.

Much has been made of the blur between film and TV, especially in the pandemic-fueled age of day-and-date ubiquity, but they remain, at heart, different disciplines — if I might be so bold, the former an art of distillation, the latter of diffusion. And I suspect the mixed-to-negative response to “Many Saints” stems in part from its confusion about what it is; in trying to be both a standalone film about mob culture in the political hothouse of midcentury America and a satisfying chapter in the saga of “The Sopranos,” it sabotages itself into being neither.

But I also suspect the problem is what we want it to be.

It’s an almost-too-perfect irony that Chase and HBO played such a forceful hand in creating the current against which “Many Saints” now swims, but the limited series, and TV more broadly, have largely replaced the mid-budget studio movie as the preferred vernacular for a certain kind of popular adult storytelling. I can’t help but think that the film reads as half-baked because we’re now so used to the slow-burn rhythm of anticipation and conversation that comes with six, eight or 10 installments, cultural training in which “The Sopranos” had a formational role.

In the course of the series, Chase developed an intuitive understanding of how to harmonize episodic beats, season-long narratives and ongoing character arcs into a gratifying whole, and I’m not sure the prequel reflects those lessons, or succeeds in translating them to feature length. Which may explain why “Many Saints” is a disappointment even to those who didn’t dislike it: It feels like an episode without a TV show, from the man behind one of the greatest TV shows ever made.

How David Chase recast old ‘Sopranos’ characters — and introduced new ones — for the big screen prequel ‘The Many Saints of Newark.’

Mary: It makes me sad, and slightly furious, that Chase still seems to be, er, chasing cinema, living out the old chestnut that film is, by its very nature, superior to television — especially given his pre-”Sopranos” pedigree, which included “The Rockford Files,” “I’ll Fly Away” and “Northern Exposure.” I thought “Not Fade Away,” his first feature film, was good, if not great, unfairly plagued by overwrought expectations of Chase finally, finally getting a crack at the big screen. I’m sure he has been badgered relentlessly about extending the Sopranos story, and I suppose we should be grateful that it wasn’t a sequel (with, perhaps, Meadow as a driving instructor).

I always wanted a Dr. Melfi spin-off (it is still possible, David Chase!!) but she was dismissed so peremptorily at the end of the series that I suppose I wait in vain. We’re about to be hit with a prequel storm of epic proportions — including “Lord of the Rings” and “Game of Thrones” — but those are series, as is the most famous and successful of the sub-genre, “Better Call Saul.”

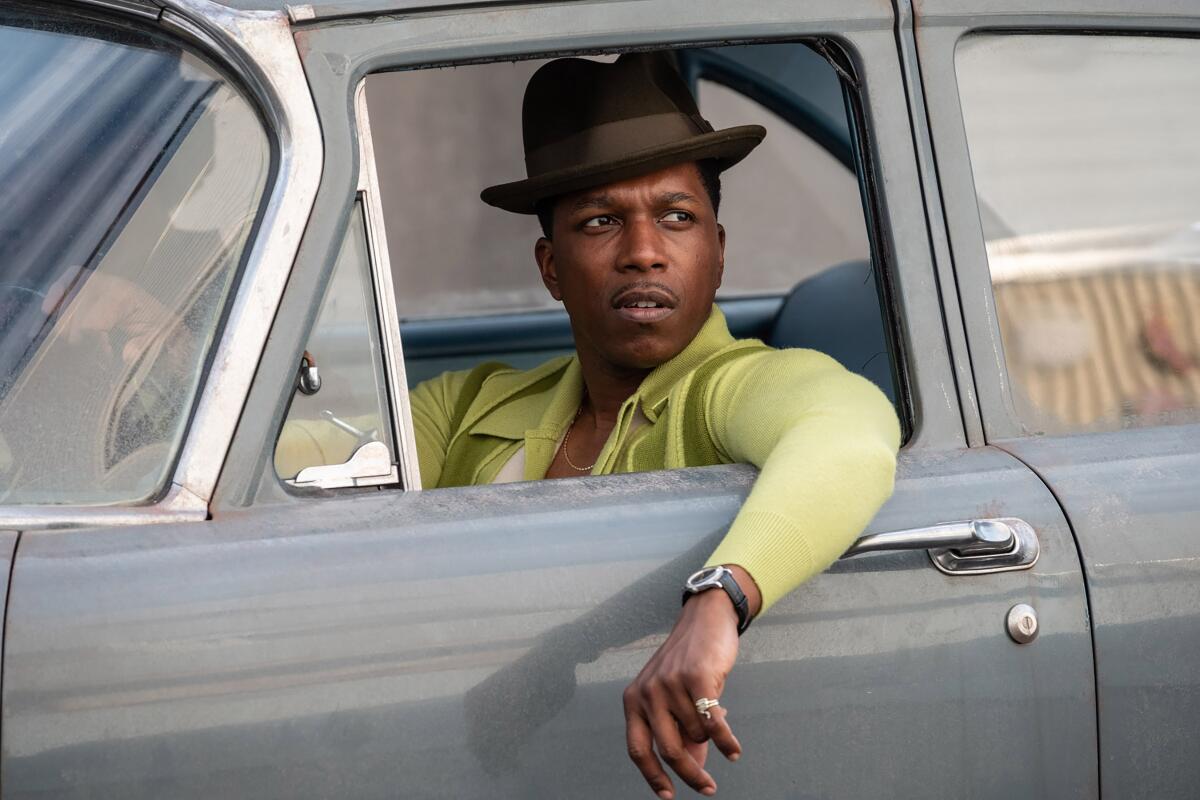

“Downton Abbey” managed to transition successfully from one screen to the other but mainly because, by the time the first film rolled around, we were all admittedly more interested in the spectacle (and, as always, Maggie Smith) than the plot. I don’t think “Many Saints” tarnishes the legacy of “The Sopranos” mainly because, beyond Michael Gandolfini’s astonishing resemblance to his father, it doesn’t seem to have much to do with “The Sopranos” at all. It has little of the series’ recognizable humanity, and almost none of its dark humor (though Silvio’s wig flip came close). The best thing about it — Vera Farmiga as Livia — is wasted, and perhaps the only thing we can hope for is, as hinted at during the end credits, a show revolving around Leslie Odom Jr.’s gangster, Harold McBrayer. That might be one way to keep tabs on Tony becoming Tony without the “name that gangster” mess. But then again, after two decades of antiheroes, maybe we need to give the mobster thing a rest.

Chang: It’s sad but also telling that it’s taken us this long to mention Odom’s performance as Harold, which is by any measure one of the better things in the movie — and which, like a lot of the better things in the movie, feels reduced by everything else. And it feels especially unfortunate since Harold’s story was clearly written to bring a fresh dimension of historical insight to “The Sopranos” saga, to illuminate the devastating violence of the 1967 Newark riots — spurred by the arrest and abuse of a Black man by police — while also examining and foreshadowing the long-standing animus between Black and Italian communities that Chase explored in the series. It’s a subject worthy of deeper engagement than it gets here; the way “Many Saints” uses the riots, as cover for a key plot twist involving Dickie, feels opportunistic to an almost offensive degree.

Like Mary, I wouldn’t mind seeing Odom’s Harold in a show of his own — or, for that matter, a movie of his own. That’s my way of politely broaching and deflecting an umpteenth iteration of the cinema-versus-television debate, which I tend to find tedious beyond words. As far as these two very different yet increasingly blurry media are concerned, I find Matt’s formulation — an art of distillation versus an art of diffusion — to be pretty apt, not to mention a master class in the art of diplomacy. And as for Mary’s displeasure at Chase for “chasing cinema,” it reminds me of just how much “The Sopranos” winkingly dealt with its own inescapable cinematic legacy. Again and again, the show engaged with — and triumphantly broke free of — the long shadow of “The Godfather” movies, acknowledging and riffing on their outsized influence in ways that felt both entirely believable and ingeniously self-reflexive. (“The Many Saints of Newark” has its self-reflexive streak, too, with its juicy double roles for Liotta, himself a Newark-born mob-movie icon.)

It’s worth recalling that “The Sopranos” ignited the so-called Peak TV renaissance, at least in part, by engaging in a degree of formal and structural experimentation that felt relatively new to the medium of serial television and was frequently (and perhaps reductively) attributed to the higher influence of cinema, or at least art cinema. But was this really Chase chasing cinema, or discovering and capitalizing on latent, intrinsically televisual storytelling possibilities that were there all along? Either way, those who remember the show as nothing more than a highly addictive narrative delivery system — a succession of twists and turns and grisly whackings — are doubtless forgetting its unnerving shifts in tone and perspective and its grotesque, hallucinatory forays into surrealism. And, yes, that radical cut to black — a parting shot that struck a lot of fans as infuriatingly avant-garde and now feels like the only possible way the show could have ended.

“The Many Saints of Newark” revisits HBO’s seminal TV drama “The Sopranos,” but the rich material would have been better off as a limited series.

None of which provides any filmmaker, even one as gifted as Chase, with any clear road maps for how to deliver an effective prequel, if such a thing is even possible. But I suspect that for “The Many Saints of Newark” to really work within its feature-length confines, its engagement with “The Sopranos” probably should have been more tangential, more mysterious, less fan-service-y. It might have unfolded over a few days or weeks rather than several years, allowing it to achieve more of that unwavering moment-to-moment specificity that Mary mentioned.

I’m spitballing here, I know. My point is that any useful return to “The Sopranos” territory will have to do more (which is to say, less) than merely lure us back in with familiar, recognizable pleasures. And I say that as someone who’s hardly unreceptive to those pleasures; clearly, to judge by the Great American “Sopranos” Watch/Rewatch of 2021, very few of us are. Rare indeed is the show that, just when you think you’re done with it — to very loosely paraphrase Silvio doing Al Pacino in a bit that will never grow old — can’t help but pull you back in.

Twenty years ago this week, “The Sopranos” was about to debut on HBO and creator David Chase was sure it would never amount to much.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.