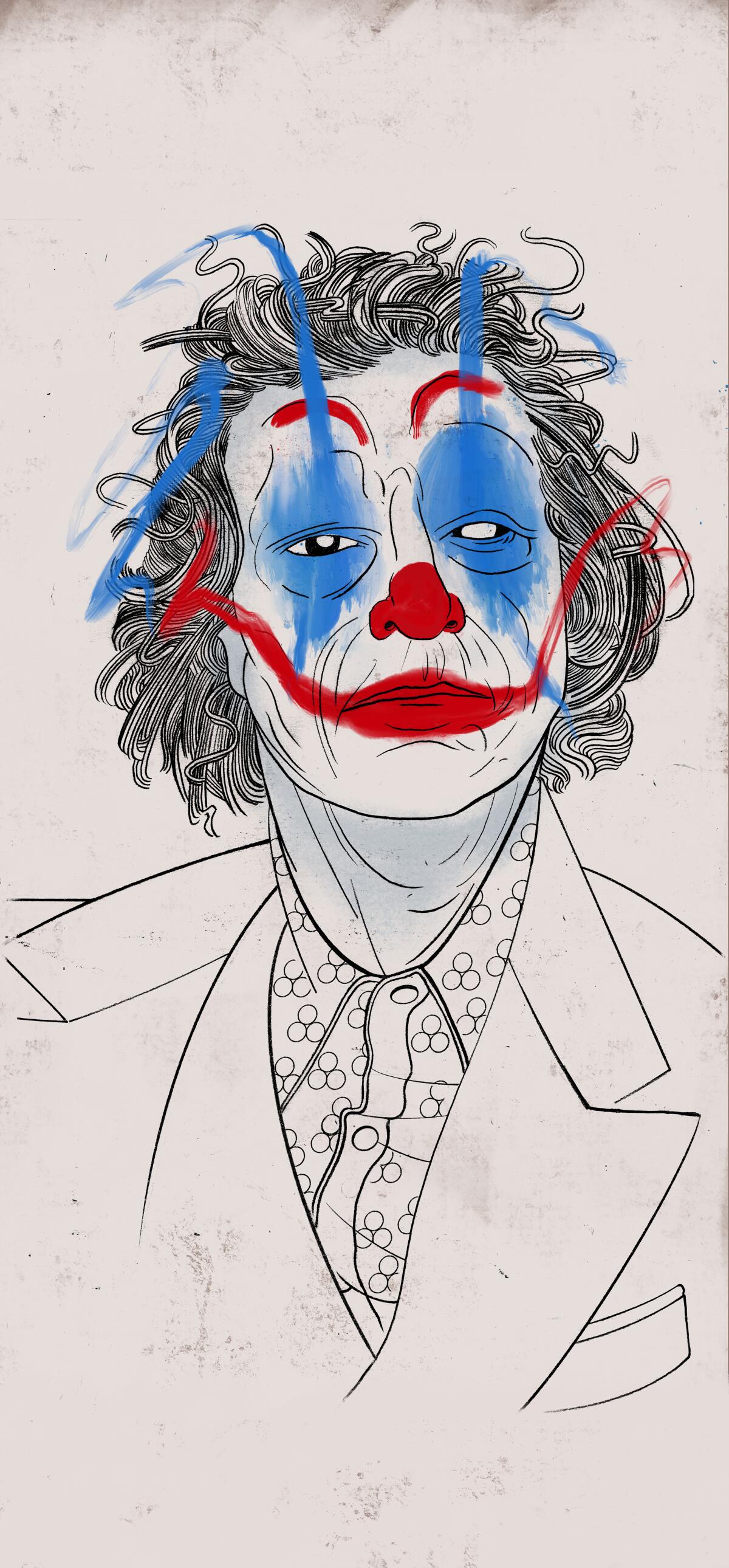

Yes, Joaquin Phoenix deserves his best actor Oscar — but not for ‘Joker’ alone

“Joker” isn’t the movie I’d give Joaquin Phoenix an Oscar for, but his greatness as an actor can’t be denied.

- Share via

In one of his greatest, most entrancing performances, Joaquin Phoenix plays a coldblooded killer who strikes terror in the hearts of the rich, the predatory and the corrupt. Having witnessed terrible things and endured horrific abuse, he now projects that abuse outward in brutal but meticulously orchestrated eruptions of violence. Apart from a sliver of tenderness in his relationship with his aging, ailing mother, he is a man incapable of giving or receiving human kindness, an outcast from society turned avenger of the downtrodden.

All this is true of Arthur Fleck, the villainous psychopath at the center of Todd Phillips’ “Joker” and the role that won Phoenix the best actor Oscar on Sunday night. But it also applies just as well to Joe, the traumatized veteran and assassin-for-hire he played in Lynne Ramsay’s brilliant, underseen 2018 crime thriller, “You Were Never Really Here.” Phoenix’s work in that movie is, I think, the deeper, richer performance of the two, the moodily restrained flip side to “Joker’s” furious histrionics. Whichever one you prefer, though, you could hardly ask for two more strikingly distinct studies in male sociopathy — or, for that matter, a more terrifying display of an actor’s range.

Joe is in many ways Arthur’s opposite, a somber, gray-bearded wreck of a man beside the Joker’s giggling, gaudily colored beanpole. (Phoenix gained considerable weight to play Joe, and then promptly lost it — 52 pounds’ worth — to inhabit Arthur’s bony, emaciated frame.) Joe hulks and broods and keeps his head down; Arthur struts and scrambles and dances up a storm. Joe has emptied himself out; Arthur consumes, and becomes consumed by, his own rage.

The key difference between the two men is not physical so much as moral. Joe, who kills sexual predators and rescues young girls from their clutches, can be plausibly defended as a hero in ways that Arthur, a vicious murderer of men who mock and manipulate him, cannot. To be sure, both Ramsay and Phillips encourage an ambivalent view of their characters; we are meant to take moral stock of their bloodlust and weigh it against our own. We can look at both Joe and Arthur and find ourselves stirred by sorrow and pity, but we are also meant to be troubled by what we see.

Another way of saying this, of course, is that we are watching a Joaquin Phoenix performance. Few American actors go as consistently deep and dark as Phoenix, and few have illuminated so many different faces of human frailty, despair and even madness; for years now he has been something of a specialist in the artistic depiction of emotional damage. He can vanish into the background or become, instantly, the volatile center of attention. His body — twitching and writhing one minute, a thing of balletic grace the next — has always felt like a conduit for forces it can scarcely withstand, let alone control. It takes almost nothing for his extraordinary face to suddenly contort with pain and fury, for those sternly handsome features to twist into a dark-lidded scowl.

Even in some of his earlier roles — an easily manipulated mark in “To Die For,” a hapless young man following his heart in “Inventing the Abbotts” — filmmakers immediately seemed to recognize that he was more than simply another mid-’90s heartthrob, that there was something more tortured, more vulnerable and infinitely more interesting at play beneath the surface. Phoenix quickly figured out how to make that something work for him. Neither of the roles that earned him his first two Oscar nominations — the treacherous Roman emperor Commodus in “Gladiator,” the troubled country musician Johnny Cash in “Walk the Line” — rank among his best work, but as examples of his talent for villainy and self-destruction, respectively, they were auspicious signs of what was to come.

Phoenix, now 45, has one of the most accomplished and adventurous résumés of any actor working today. Joe and Arthur, for all their points of connection and departure, grow out of the same wild psychological soil as Freddie Quell, the gravely stunted, sex-obsessed World War II veteran in Paul Thomas Anderson’s “The Master” (still perhaps Phoenix’s greatest performance, and one that earned him a richly deserved third Oscar nomination). They are distant cousins of Leonard Kraditor, the thwarted, suicidal romantic who finds himself caught between women and worldviews in James Gray’s haunting “Two Lovers,” and perhaps also Theodore Twombley, the lovelorn nebbish who falls for his operating system in Spike Jonze’s “Her.”

They exist on an emotional continuum with Charlie Sisters, the more damaged and volatile of “The Sisters Brothers,” and also with Doc Sportello, the perpetually zonked private eye whose comic eccentricity bleeds almost imperceptibly into melancholy in “Inherent Vice.” There is, in all these characters, a free-floating element of the absurd, an utter fearlessness about looking ridiculous. And in that fearlessness there is also a ruthless interrogation of conventional notions of American masculinity, an insistence on showing us the aching fragility beneath an exterior we have been conditioned to find hard and unyielding.

In reflecting on Phoenix’s astounding career, I find myself returning to two late actors who were among his contemporaries, and who seemed engaged in a similar project of challenging and redefining cinematic manhood as we understand it. Those two actors are Philip Seymour Hoffman and Heath Ledger, both of whom were Oscar-nominated in the same best actor category that Phoenix was for “Walk the Line” (Hoffman won for “Capote,” while Ledger was up for “Brokeback Mountain”).

Phoenix and Hoffman would go on to forge one of the great screen partnerships of recent years in “The Master,” their characters enacting a father-son, teacher-mentor bond rife with sexual tension, alcoholic addiction, generous friendship and jealous rivalry. And Phoenix, of course, would follow in Ledger’s “Dark Knight” footsteps by playing the Joker — a fact that he acknowledged in his exceptionally gracious Screen Actors Guild acceptance speech, when he described Ledger as his favorite actor.

The art of acting often requires its practitioners to make certain professional transactions with their own demons. The tragic deaths of Ledger and Hoffman (in 2008 and 2014, respectively) were taken by many members of the public as a reminder of this truth, and they led to some understandable if unfounded speculation as to whether both actors, who died of severe intoxication, had pushed themselves too far in the name of celebrity and art.

Phoenix, although still very much with us and clearly in the prime of his career, has not escaped that kind of baseless chatter himself. Not just because his own life has been marked by personal tragedy, but also because his performances are often so raw and so full of emotional risk, so under the skin and close to the bone. Rightly or wrongly, he has always seemed to have readier access than most to an actor’s inner darkness, that place where characters like Freddie, Joe and Arthur like to live.

As more than one critic has noted, Phoenix’s performance in “Joker” feels like a patchwork collage of his earlier performances, almost like a greatest-hits compilation. There are feverish flashes of Freddie, Joe and Leonard in Arthur, and there are also echoes of Phoenix’s own career. The movie’s scariest scene, in which Arthur shows up in full killer-clown regalia on the set of his favorite late-night talk show, may jog your memories of mass-media-satirizing classics like “The King of Comedy” and “Network.” But it also feels connected to a notoriously low moment from 2008, when Phoenix made a surly, incommunicative appearance on “The Late Show With David Letterman” in what he has since exposed as a piece of satirical performance art, a dark sendup of celebrity burnout.

That kind of real-world connection can make Phoenix’s performance feel excitingly, unpredictably alive at moments, even if in the grander scheme of things Arthur feels less like a flesh-and-blood human being than a meticulous psychological construct — a character whose dark, fatalistic transformation into the Joker has been mechanically plotted out. There is something ingenious about the way this expression of deadly, unbridled id has been squeezed into the schematic contours of a comic-book origin story, the way it exists at the intersection of mass entertainment and ’70s-style New Hollywood art. As Phillips said in an interview with The Wrap, his aim was to “sneak a real movie in the studio system under the guise of a comic-book film.”

But there is something diminishing about it, too, especially when you consider that it’s the imprimatur of DC Comics — and its ability to command the attention of millions worldwide — that made Phoenix so unignorable with Oscar voters this year. “The Master” and “You Were Never Really Here” were never going to muster that kind of mass recognition, but that’s precisely why those movies, and those performances, feel so exciting and uncompromised by comparison.

To watch Freddie as he goes toe to toe with his rival, or Joe as he navigates the labyrinth of his own fractured psyche, is to see an actor in utter thrall to his craft and also in thrilling command of it; you genuinely have no idea what’s going to happen next. In “Joker,” by contrast, you have a pretty good idea: Arthur Fleck’s journey can only end in murder and madness. And so it is only surprising that the long road to Phoenix’s Oscar-night coronation has been marked by a similar sense of predictability.

I’m not complaining, just assessing. Truth be told, the sight of one of our greatest living actors receiving the industry’s highest honor could never disappoint me. Joaquin Phoenix is not the first actor to win an Oscar after having been passed over for subtler accomplishments, or to benefit from those accomplishments, insofar as they have added up to a vague general perception of dueness. He gives a good, sometimes great performance in “Joker,” and what’s great about it is its eerie refraction of all those myriad Phoenix personalities, the sense that we are seeing his persona through a blood-tinged kaleidoscope.

Has Phoenix compromised his gifts for the sake of blockbuster palatability? Or has he demonstrated, in his own madcap way, what André Bazin called “the genius of the system,” the ability to harness his own creativity in service of a powerful work of art? Both can of course be true. I for one can’t wait to see what Phoenix does next — by which I mean, besides the “Joker” sequel.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.