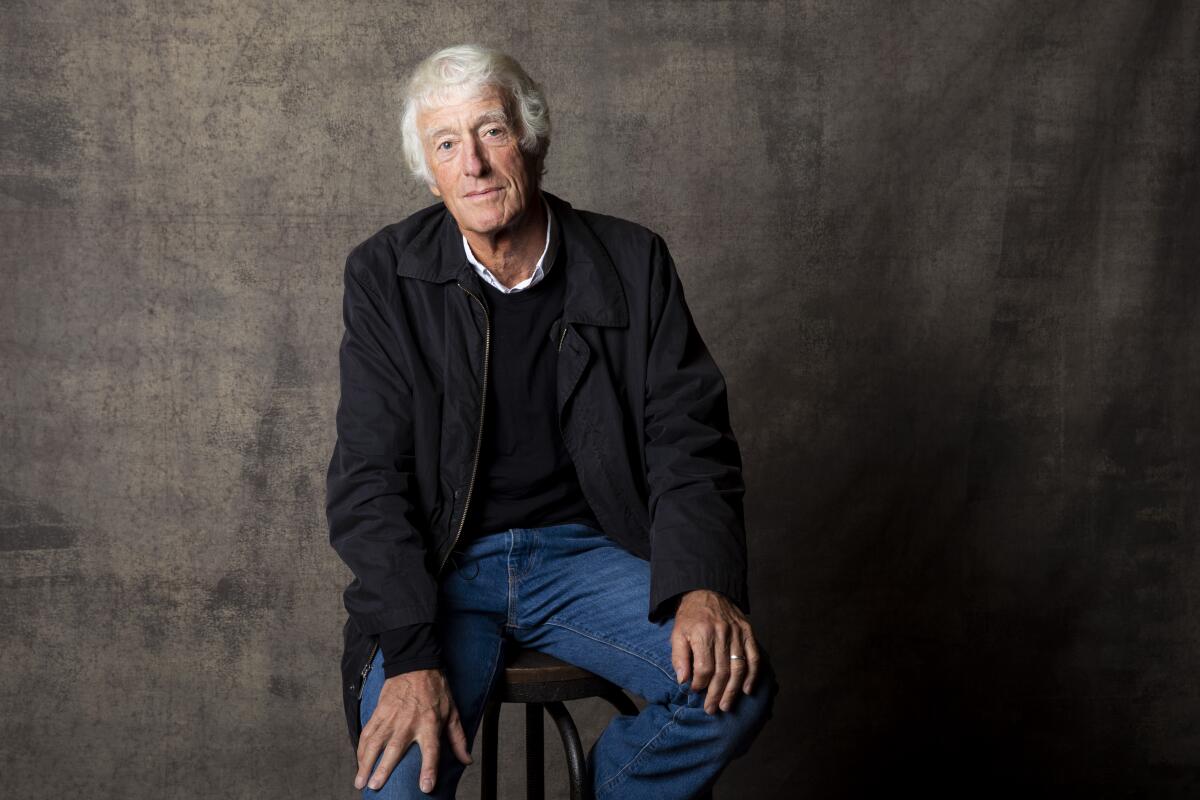

Cinematographer Roger Deakins goes to battle with director Sam Mendes in ‘1917’

- Share via

Prepare yourself for war. In Sam Mendes’ battlefield epic “1917,” set for release on Christmas Day, British soldiers Schofield (George MacKay) and Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman) must race against time to hand-deliver a message across enemy territory that will save hundreds of soldiers’ lives.

The World War I drama unfolds in real time as if it were one continuous shot tracking the heroes through the carnage.

The Oscar-winning director partnered again with “Skyfall” cinematographer Roger Deakins (an Oscar winner for “Blade Runner 2049”) to meticulously plan the harrowing allegory and technical beast. Deakins shares his story with The Envelope.

How did Mendes pitch you the story?

He mentioned the idea came to him a long time ago and it was about his grandfather who was in the war and had been a runner. That stimulated him to think more about that. Then he pulled together a whole assembly of true stories from the period and eventually put them in a script [co-written by Krysty Wilson-Cairns].

When you read the script, how did it start to visually shape itself?

The biggest thing in the script was that it said this is imagined as one shot. When we started talking about it, I wasn’t sure, as those things can be looked at as a gimmick. But when you read it, it gives you a sense of motion and pulls you in. I thought it was a really good choice.

What did you talk about in preproduction to avoid any hurdles?

We spent a lot of time discussing and scouting the locations. It’s those kinds of things that you gradually build on, and then we talked about each individual scene and blocked it out in our minds. We worked out what we thought the blocking was and what the camera would do, given that blocking.

Then that whole process went further down the road when we got the actors and developed the scenes with a camera. This way, by the time we actually had a full crew on set, we knew exactly what we wanted the camera to do and what the blocking was going to be.

Were there any obstacles dialing in the camera movement?

The biggest challenge was how to do the shots. It was an aesthetic challenge because of where to put the camera and how to move it, but it was probably more so a technical challenge of how to break down the action. We had some shots that were 8.5 minutes long and included very complicated camera moves, so we had to figure out how you break them down and how you join them together. Plus, for nearly all of the film we used one lens — a 40mm attached to an Alexa Mini LF.

Did you create any underlying rules for composition?

We always wanted to be connected to the characters in some way. With that said, we realized the process was going to be a discovery. If there was a way we could move to a wide shot that was still connected to the characters but didn’t feel like we were arbitrarily moving to a wide shot for the sake of a wide shot — that was the most important. We didn’t want the camera to suddenly be a character or observing the action. We wanted to stay with the characters, because it’s a very particular story that lends itself to that real time single shot idea.

Did the production design or the locations affect the planning?

The first thing about shooting one-offs is that you can’t change it once you shoot it. We had to figure out the timing of each scene and each shot, because you can’t adjust it later, nor can you cut out of it. Once you get the take you like, you live with it. So it was crucial that we walked through the scenes and shoot them to get a sense of the space. All the shots had to be worked out before the sets were built so they were the right size. It became quite a complicated thing.

Being a period piece, what quality of light and texture did you consider?

I was going for reality. Obviously, I couldn’t shoot with oil lamps for some of the interior bunker scenes, as I need a little bit more stop. But with the locations, the way the sets were dressed and the way the characters were costumed, we wanted it to look of the period. I haven’t put a filter on the front of the camera for the last 40 years. I think it’s the quality of light that you shoot in, the set, the color, the textures within it and how you light it that brings it all together.

With such a technical challenge, has the experience brought anything out of you as a visual storyteller?

This is something unlike I’ve ever done before. It’s totally different than something like “Blade Runner 2049.” That was about camera movement, but it was very considered. This is very fluid. You can’t get it from the trailer, but the camera hardly stops moving through the whole film, because the characters hardly stop moving.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.