Behind the scenes with the real teachers of ‘Abbott Elementary’

- Share via

A parade of first graders bursts through the doors and enters the room along with the early morning sunlight. A girl in a pink chef’s hat, a boy in a Spider-Man hoodie, a girl in a ballerina tutu, a boy with light-up sneakers, a girl in a unicorn onesie and dozens of other energetic children meander through the line, clutching their parents’ hands.

One girl, Maria, greets her “bestie” Harmony with an early valentine and receives a warm hug in return.

“Hello Xhyla, my little cheerleader,” the kids’ teacher, Kristin Minkler, says as they skip past the check-in table. “You’re good, Zariah. I got you.”

Minkler, sensibly clad in black leggings, tennis shoes and long puffer coat, informs the children that they are “going straight to school.”

But this is not a normal school.

The team behind ABC’s Emmy-winning sitcom explains how they found 80 child actors who could ‘play it real’ — and became a potential career launchpad.

Minkler is the lead studio teacher for the hit ABC sitcom “Abbott Elementary,” which means she is in charge of every child performer on the show from the moment they arrive on the Warner Bros. studio lot in Burbank. Immediately after checking in with Minkler, the young background actors — who populate Abbott’s classrooms, hallways, library and gymnasium onscreen — change out of their everyday attire and into their costumes: tiny blue polos that bear the crest of their fictional Philadelphia grade school.

When the kids aren’t busy acting opposite their TV teachers — played by Sheryl Lee Ralph, Tyler James Williams, Lisa Ann Walter, Chris Perfetti and show creator Quinta Brunson — they spend their downtime behind the scenes chipping away at their schoolwork.

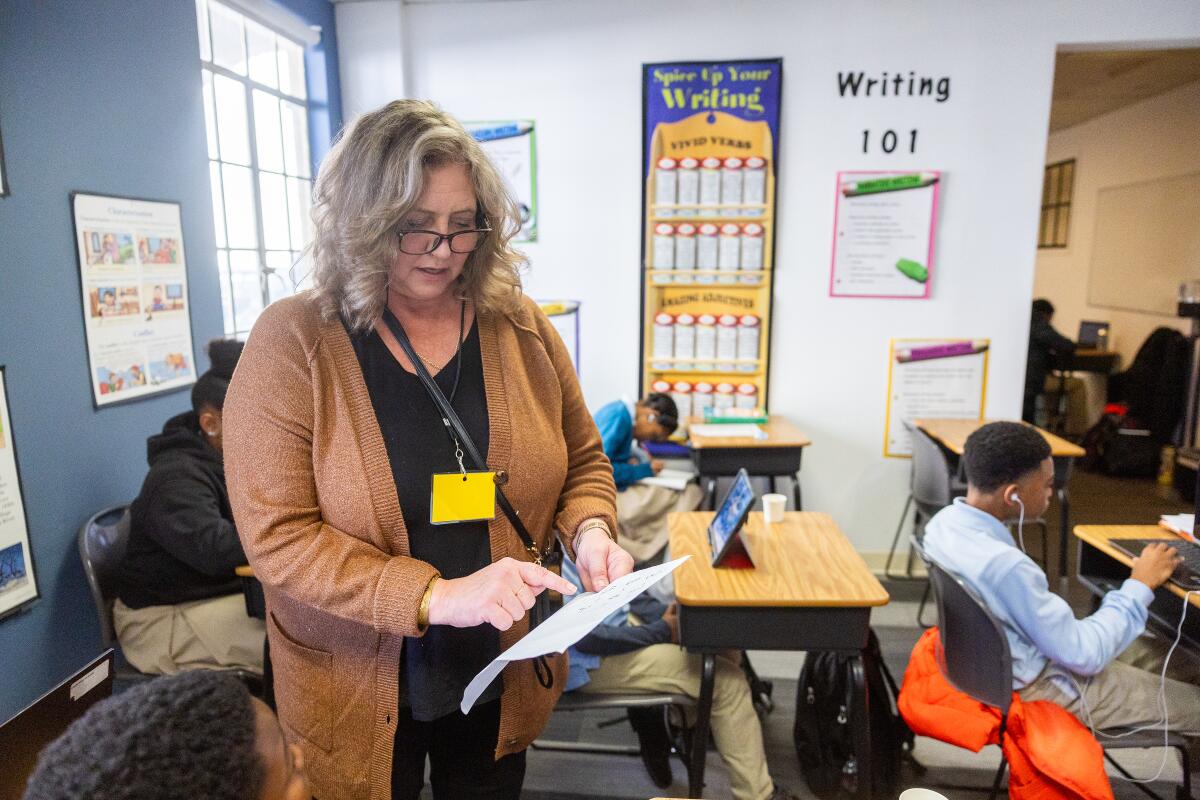

Around the corner from soundstages 15 and 16, where “Abbott Elementary” is filmed, is a dedicated learning space where Minkler and her team entertain the child actors with educational activities and help them with their studies.

The teachers fulfill a dual role as both educators and caretakers who are responsible for enforcing California’s child labor laws on set. After a production delay caused by last year’s Hollywood strikes, the studio teachers and child actors are back and busy working on Season 3 of “Abbott Elementary,” which premieres Wednesday on ABC.

“I always tell [the children], ‘This is real school,’” Minkler said. “‘It’s different from the school that you go to, but this is a real school.’ And if you’re gonna tell them it’s a real school, it needs to look like a real school.”

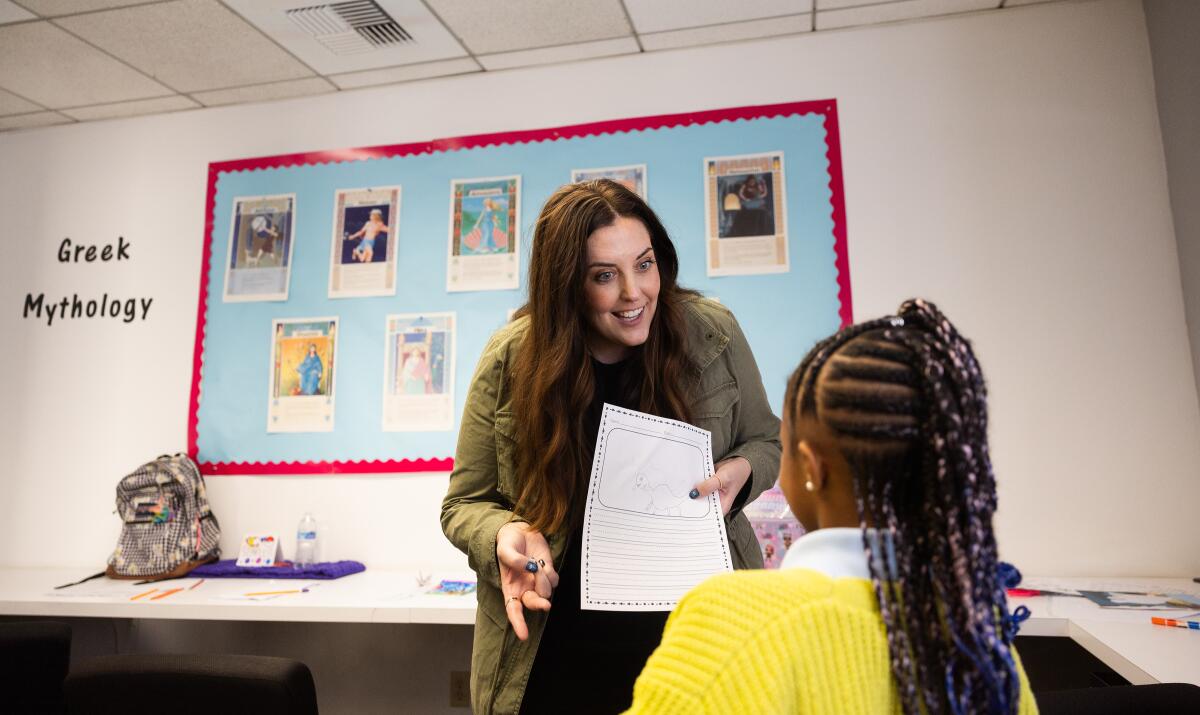

To that end, Minkler has decorated every wall of her studio classroom with colorful bulletin boards and educational resources — including miniature biographies of William Shakespeare and Langston Hughes, fun facts about the ancient Greek gods, a planetary diagram of the solar system, the periodic table of the elements, guides to converting fractions and solving algebraic equations, giant maps of the United States and the world, and motivational phrases such as “Be brave,” “Dream big” and “Never give up.”

Every piece of decor in the building — from the pink high-heel-shoe tape dispenser on Minkler’s desk to the handwritten name tags waiting for each student at their assigned seat — was procured by Minkler herself. Some of the items have been in her possession since she was a high school English teacher 25 years ago.

Also on display are various student art projects, which the show’s art department occasionally borrows or commissions for its classroom sets.

“We want them to walk in and see their art and see that this is a school, and it’s a safe space,” said studio teacher Ali Bloom. “You can come in here, you can relax, you can get your work done, you can learn something. You can be amongst your peers and feel that feeling of school.”

Because they began their careers in traditional school settings, Minkler and her studio teacher second-in-command, Sandy McNeil, can sometimes relate to the educators and scenarios portrayed on “Abbott Elementary” — which has earned glowing reviews, strong ratings and multiple Emmy Awards since it debuted in 2021. (The show’s sophomore season averaged 9.1 million viewers after 35 days spanning traditional TV and streaming platforms.)

While working as a substitute teacher in Los Angeles schools early in her career, McNeil recalled, there were instances when kids sat on tables because there weren’t enough chairs for all of the students — which isn’t far off from the kinds of funding and resource issues the characters contend with in the show.

Minkler was amused by Season 2’s Halloween episode, which sees the “Abbott” students get sugared up on candy and wreak havoc on the school — a predicament she knows all too well from her experiences both as a teacher and a parent.

As a studio teacher, “You walk the tightrope because you’re with production, but you’re there to make sure everything is OK with the kids, but you want things to run smoothly,” Minkler said.

“It really is this dance between making sure everybody is happy and everybody feels like they’re getting what they want,” she added.

“It’s a lot harder of a job than people think.”

Each season, a portion of Warner Bros.’ budget goes to studio education for its child actors, who hail from all over Los Angeles County and beyond.

According to the California Department of Industrial Relations, children between the ages of 6 and 18 who are employed on a film or TV project must complete at least three hours of school per workday. During weekdays, there must be one studio teacher present for every 10 kids on set.

“We are a show who greatly values real-life educators, so it was crucial that the teachers working here be exemplary,” executive producers Justin Halpern and Patrick Schumacker said in a statement to The Times. “Kristin, Sandy and the rest of the team’s hard-earned wisdom, patience and care ensure that our show’s young actors value education every bit as much, if not more, than making TV.”

Brunson said the production is fortunate to have such a dedicated studio teaching staff “on a show that is primarily populated with children almost every episode.”

“Abbott Elementary” can require the presence of more than 100 child actors with varying classwork, needs, dietary restrictions and schedules on any given day. Like all studio teachers, Minkler and her staff are equipped with double teaching credentials — single subject, which focuses on one core area of study, and multiple subject, which covers a general array of knowledge spanning kindergarten through 12th grade.

“I don’t know where we’d be without our studio teachers,” Brunson said in a statement. “The team is patient, kind and focused on the children and their education first while balancing the needs of the production.”

On a sunny Friday in January, six studio teachers and 48 child background actors arrived on the Warner Bros. lot to shoot a library scene for Season 3, Episode 6.

The studio classroom is divided into sections corresponding with the kids’ fictional teachers on the show. Barbara’s kindergarteners and Gregory’s first graders are on the right; Janine and Melissa’s second graders are in the middle; and Jacob’s sixth, seventh and eighth graders are on the left. As the background actors grow up, they move into different groups both onscreen and offscreen.

“You’re walking into a well-oiled machine,” said McNeil, who joined “Abbott” this season. “I’m blown away by how organized it is and how efficient.”

Child actors of varying ages filed into the studio classroom and took their seats by their name tags, shrugging off their “Powerpuff Girls,” “Paw Patrol,” rainbow and butterfly backpacks. The studio teachers floated around their sections, stopping when they saw raised hands and helping students sound out long words in their reading, tackle their multiplication tables or understand fractions.

The studio teachers “help you so much,” said Abraham, who first appeared in Janine’s class before transferring into Melissa’s. The 11-year-old background actor from Ladera Heights said that whenever he is struggling with his schoolwork at home, he’s eager to return to set where he can benefit from the studio teachers’ assistance.

“Don’t tell anybody, but they give you the answers ... if you ask them,” Abraham said, lowering his voice for effect as his dad buried his face in his hands.

“I’m just kidding,” he added with a giggle.

For creator-star Quinta Brunson, Janelle James, Sheryl Lee Ralph and Lisa Ann Walter, the series lets teachers be human. And as a result, “teachers are feeling seen, which is one of the best things about the show.”

Jaidyn, a 13-year-old background actor from Watts who started in Jacob’s class and is now a designated “hallway kid” on the show, said that sometimes the studio instructors will teach her new things or show her an easier way to learn something.

“Even though there’s ... other kids, you still get that personal attention,” Jaidyn said. “They actually pay attention and help me when I’m trying to solve a problem.”

Multiple child actors said that they enjoy the educational activities the studio teachers provide for kids who finish their schoolwork before they’re needed on set, from arts and crafts to extra math practice.

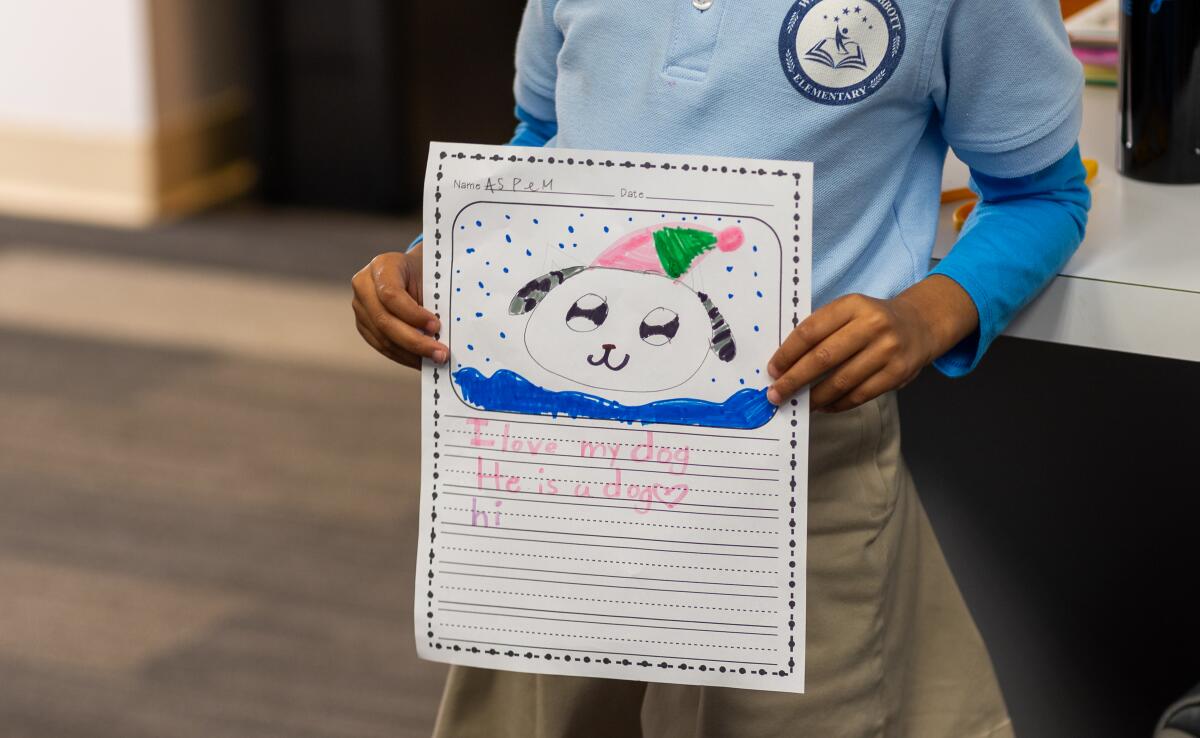

When the library shoot was delayed, for example, the studio teachers staged an impromptu “pet show” for the littlest kids. The first graders each grabbed a piece of paper and a drawing implement (one student embarked on a mission to fish out all the pink markers until Bloom persuaded her to leave some for her classmates) and began sketching their imaginary pets.

Then it was show-and-tell time.

Scarlet kicked things off to a strong start with her creation, Beardy, the bearded dragon. Peter introduced everyone to his bunny named Pete. Maria proudly presented Emma, a unicorn who plays with stuffed animals and sleeps on a rainbow.

McNeil explained that it’s in everyone’s best interests to keep the children engaged and maintain positive energy in the classroom. “If they’re happy here, they’ll be happy on the set” and deliver a better performance. “It’s all tied together,” she said.

After the pet show and a quick headcount, the studio teachers gathered the first graders in a single-file line and led them to the soundstages.

“One, two, buckle my shoe!” the children’s voices echoed across the empty lot. “Three, four, shut the door!”

Minkler was in the middle of explaining how singing exercises help the kids focus and prevent them from wandering into the street when, as if on cue, one of the first graders broke free from the queue and leaped gleefully over a puddle.

“Oop, there goes Ryleigh,” Minkler said.

Once on set, the studio teachers switch into health and safety mode, reminding the production crew when it’s time for the kids to take a break and meticulously scanning the high ceilings for any hazards, such as loose light fixtures or rigs.

McNeil likes to compare studio teachers minding child actors to Secret Service agents.

“You’re not so much looking at the president,” she said. “You’re looking at everything that’s around ... to see if there’s anything that looks potentially unsafe.”

With 55 years of teaching experience between them — mostly on film and TV sets — Minkler and McNeil are seasoned professionals when it comes to navigating tricky situations during production.

Season 2 of the ABC sitcom solidifies the bonds between the two male teachers -- and the conspiracy-minded school janitor. And, as it turns out, for the actors who play them.

Minkler has primarily worked on local TV productions, such as family shows on Nickelodeon, while McNeil has traveled the world to accompany child actors on location for major motion pictures. (One of her earliest, most loyal pupils was “The Lord of the Rings” star Elijah Wood.)

Both have experienced the logistical and financial challenges that come with freelancing full-time and had their fair share of brushes with the rare nightmare stage parent — but for the most part, Minkler and McNeil said they’ve found their studio teaching careers to be enjoyable and fulfilling.

“I’m proud to be doing this,” said McNeil, who commutes from the South Bay to work on “Abbott.”

“I wouldn’t drive three hours a day round-trip from where I live if I didn’t love this. ... I can’t think of something else I would rather do if I’m going to work in the entertainment industry. ... When I get home every day ... I feel like maybe I’ve made one little difference in the world.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.