WGA members easily ratify new contract to end 148-day strike as anxieties loom

- Share via

As members of the Writers Guild of America voted overwhelmingly in favor of a new contract that ended a 148-day strike, anxieties loomed over a coming contraction in the film and TV business that could limit job opportunities even after Hollywood gets back to work.

WGA members on Monday gave a near-unanimous endorsement of the new film and TV contract — with 99% of those who voted approving a deal.

“Through solidarity and determination, we have ratified a contract with meaningful gains and protections for writers in every sector of our combined membership,” WGA West President Meredith Stiehm said in a statement. “Together we were able to accomplish what many said was impossible only six months ago.”

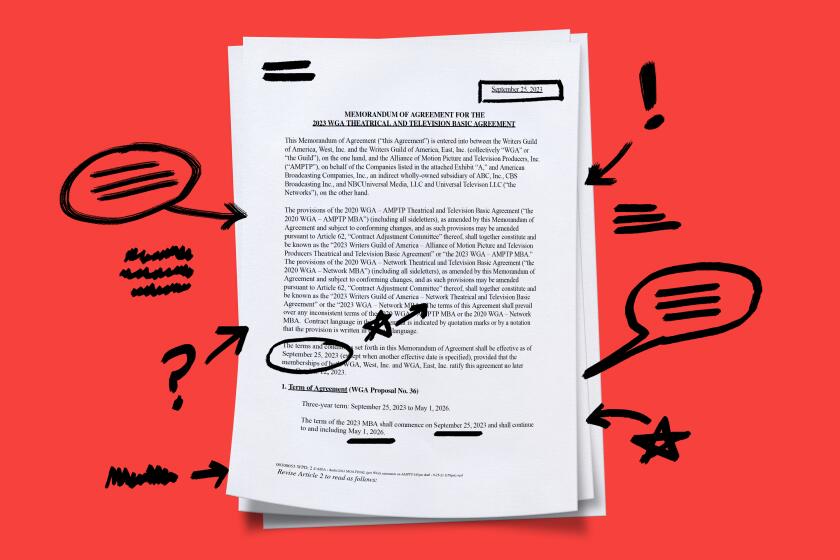

A team of Los Angeles Times journalists analyzed the Writers Guild of America’s contract with studios, marking it up line by line. See the most significant changes, the pivotal arguments and the key subtexts within this historic document.

The vote marked an official coda to one of the longest strikes in the history of the 11,500-member union. WGA members were joined by actors on picket lines in mid-July, and the SAG-AFTRA strike remains ongoing.

There were 8,525 votes cast, with 8,435 voting “yes” and only 90 “no” votes, the WGA said. The new agreement with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, which represents studios, will run through May 1, 2026.

The strong ratification was a vindication for guild leaders in their decision to hold out for gains that studios initially rejected when the strike began May 2. They did so by maintaining a high degree of solidarity from the union’s membership and other Hollywood guilds.

The new contract establishes bonuses to writers based on viewership data on streaming services, sets minimum staffing requirements in TV writers rooms depending on length of season and imposes limits on the use of artificial intelligence.

The 2023 WGA strike lasted 148 days, making it one of the longest work stoppages in Hollywood history. Why did it last so long?

In a statement Monday, the AMPTP said its member companies congratulated the WGA on the contract’s ratification, “which represents meaningful gains and protections for writers.”

“It is important progress for our industry that writers are back to work,” the alliance added.

But while the news was met with relief by many WGA members, the celebratory mood was tempered by deepening worries that it will take some time before productions get back into full swing and that job opportunities will be more scarce than before the walkout began.

Alex O’Keefe, 29, who has written for the FX series “The Bear,” strongly supported the strike, saying it made important gains for current and future generations of WGA members. But he remains concerned about his future.

O’Keefe, who relied on mutual aid and charitable donations during the strike, is struggling to find work. He said he’s not sure whether he’ll be able to afford living in L.A. and may need to move to live with his partner’s parents in New York.

SAG-AFTRA has approved a deal from the studios to end its historic strike. The actors were on strike for more than 100 days.

“Just because the strike has ended doesn’t mean that I get to make an income, that I go back to work,” said O’Keefe. “The entire industry has contracted ... before and during, and I’m sure after this strike, which means less jobs, more competition, and that will probably be used as a tool to break our solidarity and pit us against each other. We have to fight against that.”

In the wake of the WGA deal, many writers have voiced concerns that studios and streamers would use the strike as an opportunity to further cut costs and ratchet back production levels.

The WGA said the total value of the deal was $233 million, up from $86 million offered by the AMPTP.

After the murder of George Floyd in 2020 and the social movement that followed, there was a big push by studios to raise the profile of underrepresented creators and diversify their staffs, but recent exits by high-ranking diversity and inclusion executives have some questioning what the future holds for young writers of color hoping to break into the industry.

“I don’t think there’s a lot of protections,” said O’Keefe, who is Black. “It’s probably one of the major fights of the next three years — the fight to preserve the diversity and expand the diversity because it’s still a very, very white place.”

Like most WGA members, many Black writers widely support the strike but fear there will be a contraction of projects and opportunities once Hollywood gets back to work.

Even before the strike began, studios and streamers began suspending expensive deals with high-profile producers amid signs that the era of “peak TV” was over as they reassessed the challenging economics of the streaming business. Stung by heavy losses and high debt levels, studios laid off thousands of workers before the work stoppages began.

“Talking about fallout, I think what we’re seeing happening in streaming was done by the companies themselves in the last couple of years; there was a big bubble,” said Tyler Ruggeri, a features screenwriter and strike captain. “Any contraction that is happening was coming down the pike regardless, in my opinion.”

David Slack, a TV writer and producer whose credits including “Law & Order” and “Person of Interest,” added: “Yes, there’s a contraction, but the strike has nothing to do with it.”

Slack, a former WGA West board member, said the current pullback is a consequence of “profound mismanagement at the top by the people at the studios and a breach of their fiduciary duties by starting streamers with no clear way to make money.”

He noted while the strike garnered writers some major “wins,” the cost to the major studios is a “drop in the bucket of corporate profits.”

Elizabeth Benjamin, a writer on such shows as “The Flight Attendant,” said that a 20-week Amazon series she was working on before the strike just got canceled, but the writers were paid out their writers’ fees.

Benjamin said, however, that she has a pilot at Netflix.

“It’s at the outline stage. I know other writers have had their pilots killed,” she added. “My agents are actively looking for a staffing job — I need more than one job to make a living.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.