Striking writers celebrate May the 4th: ‘Without writers, “Star Wars” wouldn’t exist’

- Share via

Although the “Star Wars” franchise is set “in a galaxy far, far away,” one need travel only to Lankershim Boulevard in Universal City on a rainy Thursday morning to see Darth Vader march the writers’ strike picket lines alongside Baby Yoda.

It’s where screenwriter Rob Forman — who wore a blown-up image of Darth Vader on his torso and held a sign with “May the force be with the WGA” written on it — joined dozens of others Thursday to march in front of the NBCUniversal offices. And some, like Forman, showed up in “Star Wars” apparel to celebrate May the Fourth or Star Wars Day.

Forman said one of his earliest and most formative memories was watching a scene from the space opera’s third film, where Princess Leia, clad in a golden bikini, chokes Jabba the Hutt to death with the same chain that enslaved her.

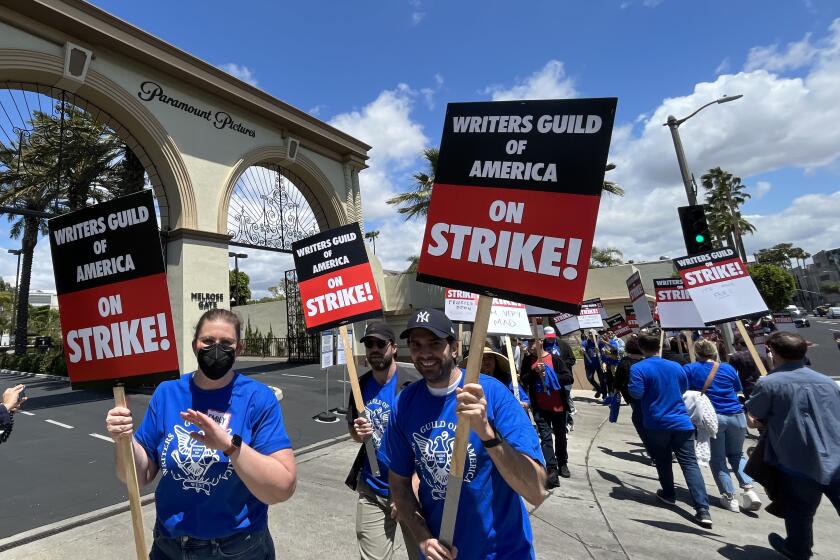

Hollywood writers formed picket lines in L.A. and New York after the Writers Guild of America called a strike for better pay and working conditions.

“It explains everything who I am as a writer,” Forman said, recalling the moment as a child when the scene flashed on the TV screen via a VHS tape. For picketers who are fans of the franchise, parallels between the “Star Wars” narrative and their fight for a new contract with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers are apparent.

“What is ‘Star Wars’ about but a scrappy, rebellious group who is not going to take fascism and having their rights and their way of life undermined and endangered from an evil galactic empire?” said writer-producer Andrea Thornton Bolden, pointing at the NBCUniversal offices, the same studio where she booked her first television job and where she worked on a Peacock show just months ago.

She walked the picket lines with a portable speaker slung around her shoulder, blasting the “Star Wars” score. As the main theme exploded from her speakers, the group of picketers erupted into yells and cheers.

The 2023 writers’ strike is over after the Writers Guild of America and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers reached a deal.

“Without writers, ‘Star Wars’ wouldn’t exist,” Bolden said. “And that has become this incredible world — from ‘Star Wars’ the movie come the toys, the theme park — and all we want is to be recognized for that creation and compensated for our labor.”

The entertainment business was in turmoil before the strike started, with firms such as Netflix, Warner Bros. Discovery and Disney laying off hundreds of employees as they face pressure from shareholders to cut costs.

The Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, which is negotiating on behalf of the studios, said that it offered a $97-million annual increase in minimum wages before talks broke down over requirements for minimum staffing and a minimum length of employment for writers. A proposed 4% increase in the first year of the contract was the highest in 25 years, according to a document the alliance released Thursday.

“Writing jobs come with substantial fringe benefits that are far superior to what many full-time employees receive for working an entire year, including employer-paid health care, employer-paid contributions into a pension plan and eligibility for a paid parental leave program,” the AMPTP said in the document.

Hollywood studios are pushing back on claims by striking writers that their latest offers were paltry.

But Forman recently worked in one of Netflix’s “mini rooms,” an outgrowth of the streaming boom. In such rooms, studios employ staffs that are about half the size of the typical staff of 10 or more. Forman and other WGA members said the same output is expected, for less pay. In Forman’s case, lasting compensation was minimal as his 20-week project hit a wall at the end and didn’t get a green light for production.

“While I wouldn’t say the CEOs of AMPTP are Emperor Palpatine,” Forman said, referring to one of the chief “Star Wars” villains, “we are in the fight for our lives and our careers. Technological changes and shifts have destroyed a former way of life — we have to recognize that in our contracts.”

Among those major changes, along with the streaming boom, has been the growing prevalence of artificial intelligence.

At the bargaining table, the WGA had sought assurances from studios that AI-generated text would not be used as source material and that AI cannot write or rewrite scripts, proposals that were rejected, said Ellen Stutzman, a chief negotiator for WGA who picketed Thursday.

“Those are pretty reasonable demands for the true human authors of the work — to not have some system take all of our content and plagiarize it,” Stutzman said.

A person familiar with the negotiations said Wednesday that the studios assured the WGA that current contract language already protected writers. The AMPTP countered by offering to meet annually to discuss advances in AI and to approach things on a gradual, case-by-case basis.

In the days before the Writers Guild of America called on members to strike, the creators of hit shows, including ‘Shrinking,’ ‘The Last of Us’ and more, gathered to discuss the state of the industry.

AI continues to be a main point of conversation and concern at picket lines — and such shared struggle over the last several days is something TV writer Mark Rozeman has found invigorating.

“We work in isolation a lot of the time — oftentimes we can be in our own head,” Rozeman said. A plush Baby Yoda rested against his chest, nestled inside a pouch that hung from his neck. If not for his glasses, his first choice would have been to wear his Boba Fett helmet.

Rozeman recently worked on the show “The Good Doctor,” where he was allowed to be present on set as a writer and remain on staff until post-production, an experience he knows is increasingly rare for his colleagues.

“I know a couple of people who have worked on a couple shows and have never set foot on set,” he said. “And that has to change.”

Rozeman said he draws inspiration from the “Mandalorian” series — a spinoff of the “Star Wars” films, which birthed the ubiquitous Baby Yoda (Grogu) character. The show’s titular character, played by Pedro Pascal, is a reluctant hero, traveling from planet to planet and aiding those who need his help with their own fights.

The current writers’ strike is just the latest in Hollywood. Since the 1950s, writers gone on strike eight times.

“And that’s what I feel like we all need to feel as a collective — we’re not just fighting for us, we’re fighting for future generations,” he said.

Those future generations may include screenwriters Chelsea Perrotty Talbot and Brian Barnes, who hope to become WGA members as they look to join more projects. The two currently work in podcasting, but they have their eyes on careers as full-time film and TV writers.

“I’m a dad of two,” said Barnes, wearing a “Star Wars” T-shirt. “So I want to make sure once I get into the WGA and enter the industry as a writer that I’m able to support my family as well.”

As productions shut down due to the writers’ strike, local prop houses, florists and caterers worry about their future and loss of work, as their business costs continue to rise.

Talbot, who had fashioned her hair into Princess Leia buns, agreed, drawing additional parallels with “Star Wars.”

“The spirit of ‘Star Wars’ is rebels, and how much more rebellious can you get than striking to get what you want,” she said.

As rain poured down on the picket lines, water bounced off writer Montserrat Luna-Ballantyne’s Darth Vader helmet. A new WGA member, she carried a sign, “Even Darth Vader thinks the AMPTP is too evil.” She said the helmet, which she borrowed for the occasion, belonged to her fiancé — she’s “more of a Trekkie.” Another picketer carried a sign reflecting some artificial-intelligence anxiety: “Scripts written by AI: R2-FU!” it read, with a drawn picture of a deceased R2-D2.

Beyond the puns and gimmicks, Forman said the “Star Wars”-themed march was an effort to embrace the fun of the moment.

“This is only Day 3, and I know that we are very far apart from what the studios want to give us versus what we might accept,” Forman said, “So anything we can do to put a smile on a face, to encourage members to keep coming out, to walk for four hours, to hold a picket sign, it’s gonna be very necessary, ‘cause they want to grind us down, and we have to lift ourselves up.”

Times staff writer Anousha Sakoui contributed to this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.