- Share via

Randall Emmett was fuming.

It was the producer’s first time in the director’s chair, and things weren’t going well. For the last half-hour on the set of “Midnight in the Switchgrass,” the filmmaker and his colleagues had been trying to persuade Bruce Willis to kick open a door.

A voice coming through the actor’s earpiece coached him through his lines. A stunt coordinator gently attempted to guide him. Yet, take after take, Willis did not seem to understand, according to seven crew members who were present for the late-night shoot. Emmett rose from behind the video monitor and mimed the actions, urging Willis to emulate him. When the effort failed, the director left the set in frustration, three of the crew members said.

“Did I do something wrong?” Willis asked, searching the concerned faces of the below-the-line team.

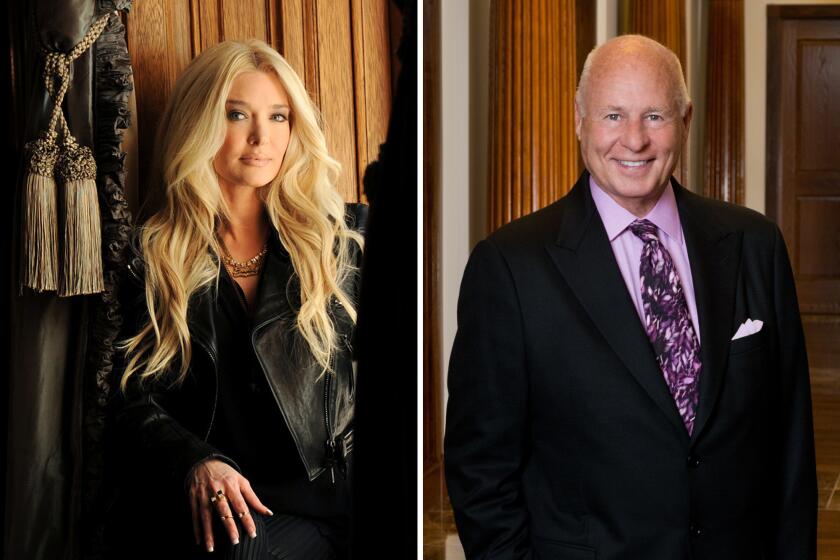

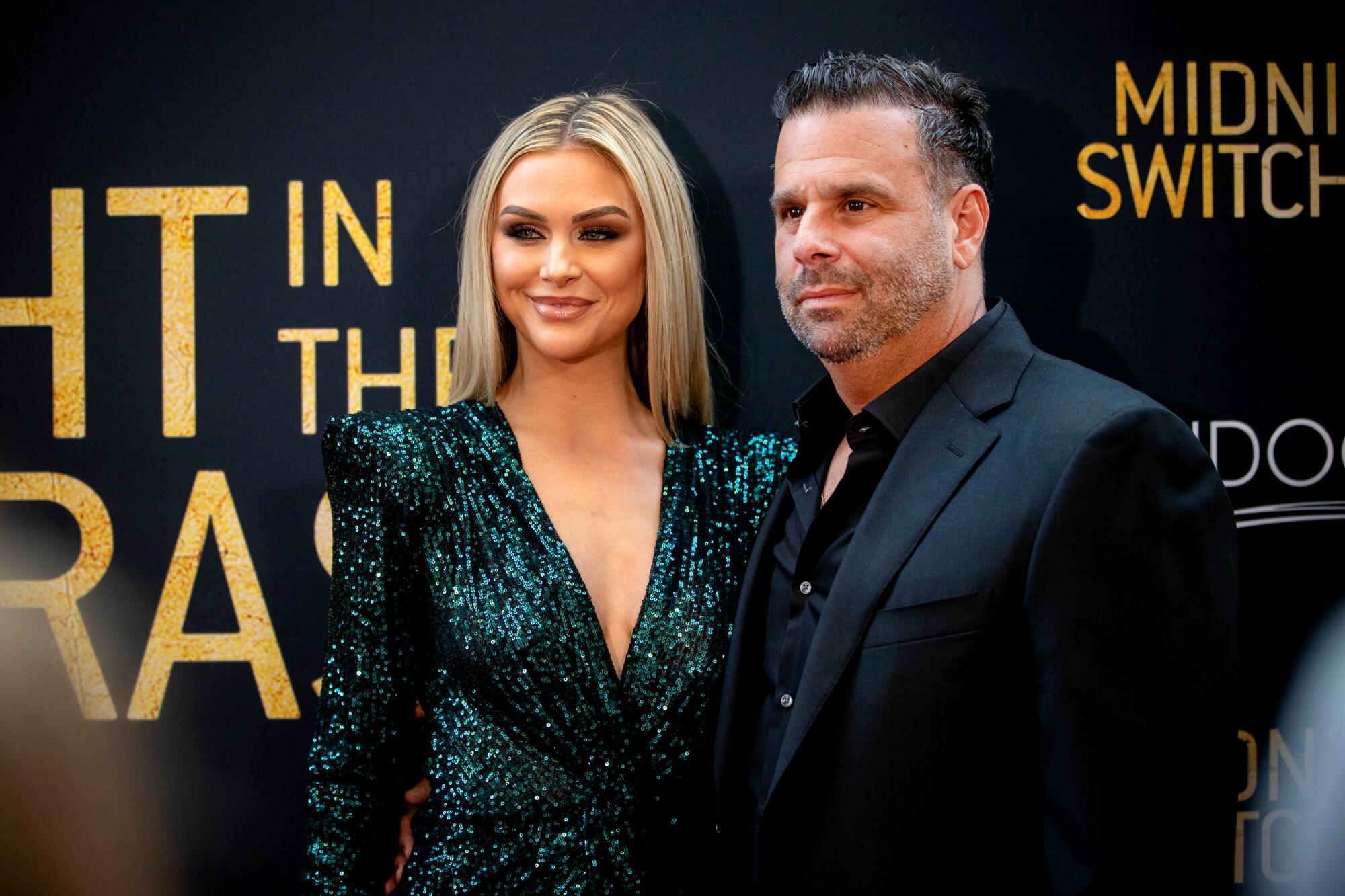

That night, Emmett’s then-fiancee, Lala Kent, said Emmett called her crying.

“I can’t do this anymore,” Kent recalled him saying in a call overheard by two other people. “It’s just so sad. Bruce can’t remember any of his lines. He doesn’t know where he is.”

‘Die Hard’ and ‘Pulp Fiction’ actor Bruce Willis ends his acting career after being diagnosed with aphasia, his family announces.

But in the 15 months after filming “Midnight in the Switchgrass,” Emmett made five more movies with Willis.

Emmett, in a statement to The Times, denied the conversation with Kent occurred or that he was aware “of any decline in Mr. Willis’ health.”

On that day in September 2020, few people outside the insular world of low-budget action filmmaking knew Willis was battling a condition that made it difficult for him to understand or express speech. But as The Times previously reported, it was an open secret on movie sets.

“Our stunt coordinator mentioned he was struggling,” said Alicia Haverland, a property master on “Midnight in the Switchgrass. “Our first [assistant director] saw he was struggling. You would have to be blind to not see him struggling.”

In March, his family announced he had been diagnosed with aphasia and was ending his career.

Willis’ enduring appeal had helped propel Emmett’s production company, Emmett/Furla Oasis, to success; the 51-year-old producer used the Willis name and face to sell his films around the world. Since 2006, the actor has appeared in two dozen of the firm’s projects — and the pace of the output heightened as Willis’ health declined.

For years, Emmett had flourished on the margins of Hollywood, producing films that featured cameos from big-name stars like Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone and often went straight to DVD. But by 2019, he was flirting with Hollywood glory. He’d produced a couple of genuine blockbusters, and was in line to claim an Academy Award as one of the producers of Martin Scorsese’s Oscar contender “The Irishman.” He had easy access to private jets, friendly contacts at gossip site TMZ, and a Los Angeles Police Department officer who described himself as Emmett’s “business and security manager.”

A year later, the walls were closing in.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

A review of hundreds of court filings and internal company records, as well as interviews with three dozen former associates, depicts an empire that is crumbling. The once-high-flying producer faces lawsuits and mounting debts, as well as allegations of abuse against women, assistants and business partners. He is accused of inappropriate behavior with women, including offering acting work in exchange for sexual favors, and of forcing assistants to conduct dangerous and illegal activity on his behalf. Through his spokeswoman, Sallie Hofmeister, Emmett denied these allegations.

Emmett used an array of tactics to try to keep these allegations secret, including entering into nondisclosure agreements and allegedly promising a payment of about $200,000 to a female accuser, which Emmett has denied.

Emmett and his company now are confronting nearly a dozen lawsuits, including several from former financiers, an insurance company and a prior landlord, all clamoring to be repaid their portion of more than $25 million in outstanding loans and disputed payments. Several lawsuits accuse Emmett’s company of misrepresentation and civil fraud.

The Writers Guild of America West won a $541,464 judgment against EFO last year after it filed a claim on behalf of writers who alleged they were shortchanged for their work on an Emmett project.

“His normal mode of business is being sketchy,” said Teresa Huang, a writer on that project. “He just spins all these plates in the air and doesn’t care how they crash.”

Times reporting has played a starring role in ‘The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills’ this season. Here’s our guide to Erika Jayne and Tom Girardi.

In a statement, Emmett rejected Huang’s assessment and blamed the allegations contained in this story on Kent, a reality TV star with whom he has a child. “These allegations are false and part of a now-familiar smear campaign orchestrated by Randall’s ex-fiancee to sway their custody dispute,” said Hofmeister. Emmett and Kent, a cast member on Bravo’s “Vanderpump Rules,” currently share custody of their child.

Willis’ attorney, Martin Singer, declined an interview request on the actor’s behalf.

“My client continued working after his medical diagnosis because he wanted to work and was able to do so, just like many others diagnosed with aphasia who are capable of continuing to work,” Singer wrote. “Because Mr. Willis appeared in those films, they could get financed. That resulted in literally thousands of people having jobs, many during the COVID-19 Pandemic.”

A wheeler-dealer

In a town that is home to creative geniuses as well as quick-buck hustlers, Emmett occupies a lucrative niche in between. He’s made more than 120 movies, most of which have been critically panned. His specialty is cranking out low-budget, high-testosterone, assault-gun-and-explosions films and recruiting stars such as Willis, Stallone, Mel Gibson and other older white men whose enduring cachet has lured investors and generated overseas sales. Although he isn’t among the few movie producers who are recognizable by name — Kevin Feige, Jerry Bruckheimer, Megan Ellison — Emmett had just enough success to attract young women, aspiring actors, ambitious assistants, deep-pocketed investors and even big-name stars seduced by the promise of fame, fortune or both.

With his trademark five o’clock shadow, black T-shirt, cargo shorts and white shell-toe Adidas sneakers, Emmett has worked overtime to hone his image as a Hollywood tough guy — a wheeler-dealer, high-stakes poker player who beats the house.

His parents sold insurance in his native Miami, but as a child, Emmett yearned to be in entertainment. In eighth grade, he began acting in TV commercials but was mocked for being a goofy kid who was interested in the arts.

After graduating from Miami’s prestigious New World School of the Arts, he went to college in New York on an acting scholarship.

“Everyone else at film school wanted to be a writer or director or actor,” Emmett told The Times in 2012. “I was the only one who wanted to be a producer.”

After graduation in 1994, he moved to Los Angeles. He landed a coveted internship with his distant cousin, Bruckheimer, the blockbuster movie producer behind “Top Gun” and “Pirates of the Caribbean,” and then became an assistant at International Creative Management talent agency.

At 24, he got a job as Mark Wahlberg’s assistant, a gig that became central to Emmett’s origin story and the foundation of his career. In the actor-producer, he had a role model and a foil. In 2012, Wahlberg told The Times that Emmett once challenged him to a wrestling match. “I had to body-slam him. Then he wanted it again.”

(Wahlberg’s manager said he could not be reached for comment.)

It was as Wahlberg’s assistant that Emmett began cultivating the kind of cool that HBO’s “Entourage” — a show produced by Wahlberg and based loosely on his rise — showcased more than a decade ago. Indeed, Emmett claims to have helped inspire the show’s weed-dealing driver, Turtle. (Multiple reports have noted that the character was actually based on another of Wahlberg’s assistants.) Throughout his decades in Hollywood, Emmett, like the guys on that series, would flaunt luxury cars and expensive real estate, date a bevy of much younger women and party at roped-off clubs.

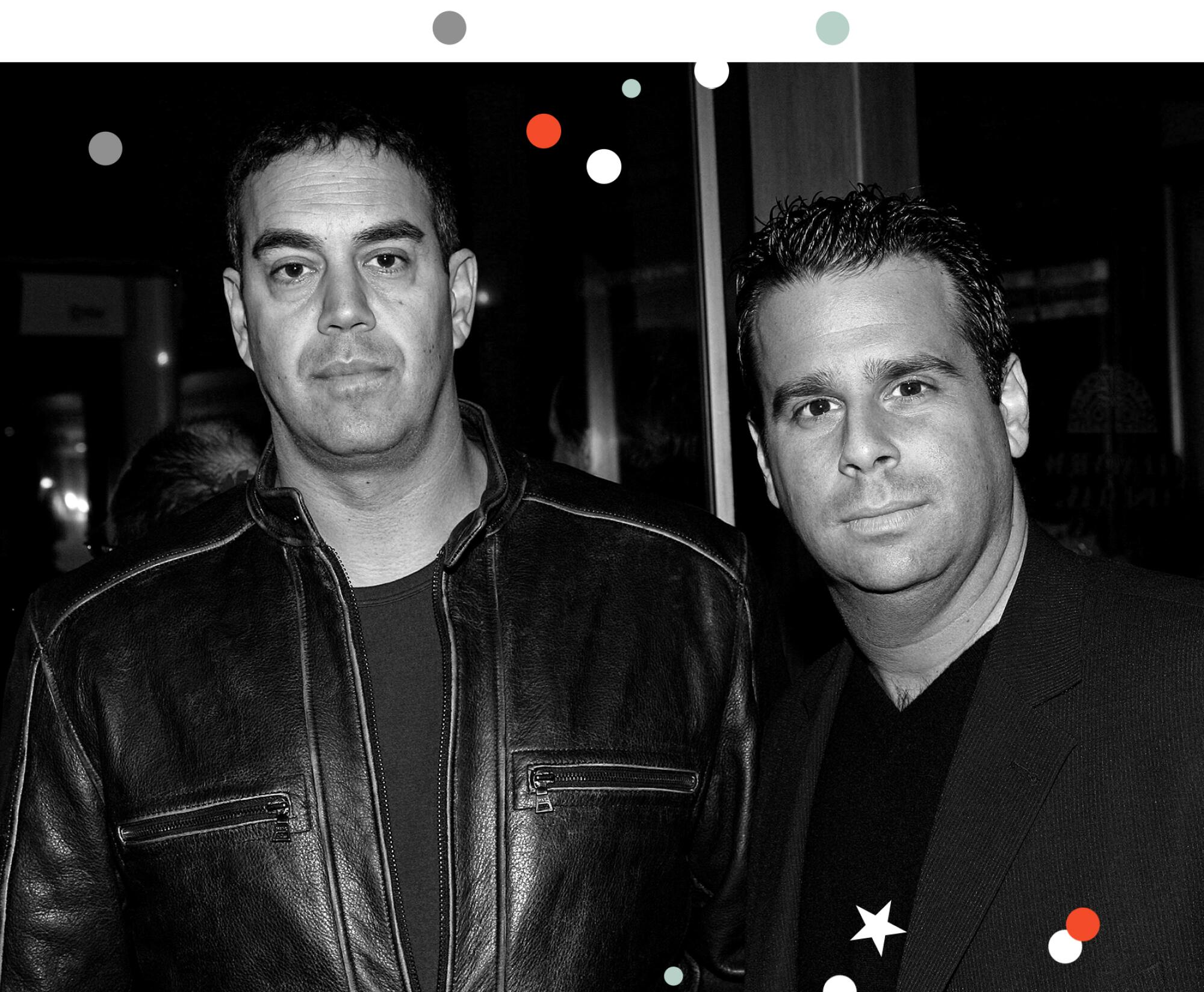

Emmett found his first loyal investor in George Furla, a former stock trader and hedge fund manager who’d put some money into a modeling agency and surprised Emmett by backing his 1999 buddy drama “Speedway Junky” with $30,000.

The pair founded Emmett/Furla Films. Furla, who declined interview requests, handled the finances, while Emmett became the self-described “loud and obnoxious” frontman.

“If you throw Randy out the door, he comes in the window,” Emmett’s film producing mentor, Avi Lerner, told The Times in 2012. “If you throw him from the window, he comes down the chimney.”

Emmett’s trademark films, dubbed “geezer teasers” in a 2021 New York magazine article that called Emmett “Hollywood’s worst filmmaker,” mined the box office appeal of Hollywood heroes of an earlier era. On a recent YouTube broadcast, he kidded that he isn’t a B- or C-level producer: “more like H-level.”)

“For a lot of people in Hollywood, Randall is the person who can help you get the movie done,” said Michael Polish, who has directed three Emmett films. “He gives people their chance, and not a lot of people in Hollywood will do that.”

Emmett’s drive, and results, attracted a large investment from Dubai-based Oasis Ventures, which in 2013 acquired a one-third stake, renaming it Emmett/Furla Oasis.

Hollywood took notice of Emmett and Furla that year. Universal Pictures released their film “Lone Survivor,” which was written and directed by Pete Berg and based on a real-life story of Navy SEALs conducting a failed military operation in Afghanistan. The film, which starred Wahlberg, was praised by critics and raked in $155 million worldwide. It gave Emmett newfound credibility after years of producing mediocre fare like “Mercenary for Justice” with Steven Seagal.

Suddenly, Emmett could attract big stars and hungry investors. His Instagram account shouted his ambition: @randallmogul.

Emmett also became an unlikely savior that year for one of the industry’s greatest filmmakers. Martin Scorsese had tried for 15 years to secure financing for a project about Portuguese Jesuit priests in the 17th century investigating Catholic persecution. None of the studios would touch “Silence,” but after a call from Scorsese’s super-agent Ari Emanuel of WME, Emmett jumped at the chance.

During his first meeting with Scorsese, he “was perspiring and hyperventilating,” Emmett recalled during a 2014 conversation with students at New York’s School of Visual Arts. “And I just went in the room and he said: ‘Why should I make these movies with you?’ I said: ‘Cause you’re the man and I’ll do whatever you f— say, basically.’ He’s like, ‘I love this kid. All right, give him the movie.’”

Emmett and Furla reportedly raised half of the $46.5-million budget for the film featuring Adam Driver and Andrew Garfield, which The Times described as a “masterwork of spiritual inquiry.” In exchange for backing “Silence,” Emmett earned a producing credit — and eventually, an Oscar nomination — on Scorsese’s next film, the brooding 2019 mob epic “The Irishman” for Netflix.

Scorsese’s publicist said the director was unavailable for comment.

‘I’m not a creep, I promise’

Despite his prolific film resume, Emmett may be best known for appearing on reality television as Kent’s fiance (and then ex-fiance) on the last two seasons of “Vanderpump Rules.”

On the Bravo show, Emmett projected the image of a Hollywood power broker who drove a Rolls-Royce convertible and lived on Mulholland Drive. Kent told friends that he’d offered to give her a Range Rover the morning after she “let him hit it” for the first time in 2015.

The couple were together for nearly six years and had a daughter before their relationship imploded. Last fall, one of Kent’s fellow cast members alerted her that pictures of Emmett exiting an elevator with two young women, taken by an onlooker in Nashville, were circulating online. (Asked about the images, Hofmeister said: “Randall enjoys socializing with friends. In Nashville he was hanging out with a large group of people, men and women.”)

Within hours of the photo leak, Emmett was back in L.A, where Kent demanded that he share the contents of his phone. When he refused, she said she grabbed it away from him.

Natasha Henstridge was watching a movie on Brett Ratner’s couch when she fell asleep.

“He ran after me, tackled me and knocked me to the ground,” Kent said, echoing claims she made in her request for custody of their daughter. “I used every ounce of strength to get him off of me as he was trying to pry it from my hands. … That was when I knew, for sure, that there was a lot he was hiding.”

The Times spoke with five people who confirmed Kent told them about Emmett tackling her to the ground within days or weeks of the altercation. Emmett, however, denied a physical fight occurred. His team provided The Times with a declaration from his longtime nanny, Isabelle Morales, who said that “neither was on the ground.”

“I witnessed Randall and Lala fighting over his phone,” Morales said. “The only physical interaction I saw was Randall taking back his phone from Lala.”

Kent sought “to keep her name in the press, and remain relevant in reality television,” Hofmeister said in the statement.

Emmett had good reason to protect the iPhone. It was the keeper of his secrets — the tool he is accused of using to send lewd text messages to women, hunt for sexual prospects on Instagram and email his lawyer about wiring money to women in exchange for their silence.

Through interviews and reviewing previously confidential documents, The Times has learned that several women have accused Emmett of pursuing them in inappropriate ways — one alleged she was offered acting work in exchange for sex — even as Hollywood began to reconsider the way its powerful men treated women.

“I used every ounce of strength to get him off of me as he was trying to pry [his phone] from my hands. … That was when I knew, for sure, that there was a lot he was hiding.”

— Lala Kent, echoing claims she made in her request for custody of their daughter

One woman, who declined to be named for fear of retribution, said that she was leaving a bar around midnight in 2014 when a Rolls-Royce pulled up beside her on Ventura Boulevard and a man she had never met rolled down the window. It was Emmett.

“I’m not a creep, I promise. I’m a movie producer, you can Google me — please Google me,” she said he implored. The Times spoke with a friend of the woman who said her friend shared this account, but Emmett denied the incident occurred.

Another aspiring performer was just 23, with a few minor TV credits to her name, when she met Emmett. The producer, then making a string of movies with rap star Curtis “50 Cent” Jackson, introduced himself to her as a “well-known and established movie producer,” according to a letter written to Emmett by attorney Gloria Allred.

Allred’s letter, which The Times reviewed, was dated Oct. 5, 2021, and sent to Emmett via FedEx and email. In it Allred alleges that the producer explicitly told the woman, who declined to make her name public, “that to receive acting work from [him], she would have to perform sexual favors.” The letter then cites a text exchange in which Allred’s client asked Emmett if she’d won an acting role she’d auditioned for in one of his projects.

“Yes. one day of work and u need to fuckme hun,” Emmett responded, according to the letter.

Hofmeister confirmed that Emmett did receive the letter but said he “adamantly denies” the allegations in it. Allred declined requests for comment.

Over the next three years, Allred’s client had minor roles in two more of Emmett’s films.

During this period, Allred’s letter alleges, the woman gave Emmett massages and oral sex, allowed him to digitally penetrate her and stood nude in his office while he masturbated.

She complied with Emmett’s requests, the letter says, because she was “seeking to further her career” and did not want to “anger an important producer in the industry.”

Interviews with multiple members of the “Rust” crew paint an hour- by-hour picture of a cascade of bad decisions that created a chaotic set on which a lead bullet was put into a prop gun.

Whenever Allred’s client rebuffed Emmett’s advances, she said, he told her he would not give her the roles they had discussed.

The incidents caused her to feel a “deep sense of self-loathing and self-hatred” that led her to seek weekly therapy beginning in 2016, Allred said. The lawyer went on to invite Emmett to engage in “an expeditious confidential mediation process” to avoid civil litigation.

On Jan. 2, 2022, Emmett was sent a settlement agreement that stipulated he would pay Allred’s client about $200,000 over the course of two years. A person familiar with the situation said Emmett printed, signed and scanned that agreement, although he denied doing so.

Just two months after finalizing the settlement, Emmett sent an unsolicited Instagram message to a 30-year-old woman in Las Vegas whose feed featured dozens of photos of herself and her boyfriend. This woman told The Times that Emmett — whom she’d never met — messaged her from his account using the social media platform’s “vanish mode” setting, which permanently deletes any text or pictures after they are seen by both users.

According to a declaration filed in the custody proceedings and reviewed by The Times, Emmett asked her to “f— on the dl” and “do heroin and meth,” among other things. She did not respond and was so alarmed, she recounted, that she used the camera from her laptop to capture the Instagram messages on her phone. She included screenshots of those images with her declaration.

Hofmeister provided proof of negative drug tests Emmett has taken as part of the ongoing custody dispute.

“He is working hard on his sobriety and very proud that he has stayed clean for almost a year,” she said.

A person close to Emmett said there was no forensic proof Emmett sent the messages to the Las Vegas woman.

Despite being unanswered, Emmett’s DMs continued for two weeks, the Las Vegas woman said. Then she received a string of similar WhatsApp messages from an unknown number.

She reached out to a friend who knew a “Vanderpump Rules” cast member and confirmed that the unknown number matched Emmett’s. She said she blocked his number.

“I was shocked, concerned, and afraid because Randall is a stranger to me,” the woman wrote of Emmett’s behavior in the court document. “His persistence despite my never responding to a single message from him is frightening.”

Offers of payment

Emmett paid women to sign nondisclosure agreements, or NDAs, requiring them to keep mum about his intimate relationships.

He tried to get Kent to sign one early in their relationship, his ex-fiancee told The Times.

In the summer of 2016, she was about to start filming the fifth season of “Vanderpump Rules,” and producers wanted to include her new boyfriend on the show. But their romance was a delicate subject: Emmett was still legally married to actress Ambyr Childers, though he told Kent that they were separated.

To figure out how to handle the subject on television, Kent said Emmett suggested that she meet with one of his attorneys, Keith Davidson, who once represented Stormy Daniels in her legal battle against Donald Trump. Kent brought her mother, Lisa Burningham, along to the attorney’s Wilshire Boulevard office for one of their meetings.

Inside, Kent said Davidson put a stack of papers in front of the women: an agreement stating that Kent would receive $14,000 in exchange for keeping her relationship with Emmett a secret.

“I said: ‘We’re done,’” Burningham recalled, and she and her daughter left the office.

Davidson, in a response to The Times, said attorney-client privilege prevented him from discussing the matter. A person close to Emmett said the account was inaccurate but did not provide any details.

Kent and her mother said she did not take the $14,000 offer, and Kent ended her relationship with the producer. But after his divorce with Childers was finalized in December 2017, Emmett and Kent reentered a serious relationship. They remained a couple until she learned of his alleged infidelity following the Nashville incident in October 2021.

After those photos of Emmett with other women surfaced, Kent said she was suddenly bombarded with messages. Several individuals claimed that a Florida model had been having an affair with Emmett, and Kent checked out the Florida woman’s social accounts.

When the woman noticed that Kent had viewed her Instagram story, she called Emmett on Nov. 28 and recorded the conversation without his knowledge. The Times reviewed the recording, in which the woman fretted that Kent “obviously has a lot of details if she knows my Instagram account.”

“There’s no evidence of us ever having hooked up,” Emmett responded. “I want you to say — if she ever tries to get to you, you can say, ‘Hey, I dated [his assistant].’”

Later that day, the Florida woman texted a friend, saying she was “trying to figure out a way to leverage the whole situation to get money” in exchange for “my silence.” (The Times reviewed the messages.) “I should say some thing like a tabloid came to me with a certain amount of money and they found proof of some sort.”

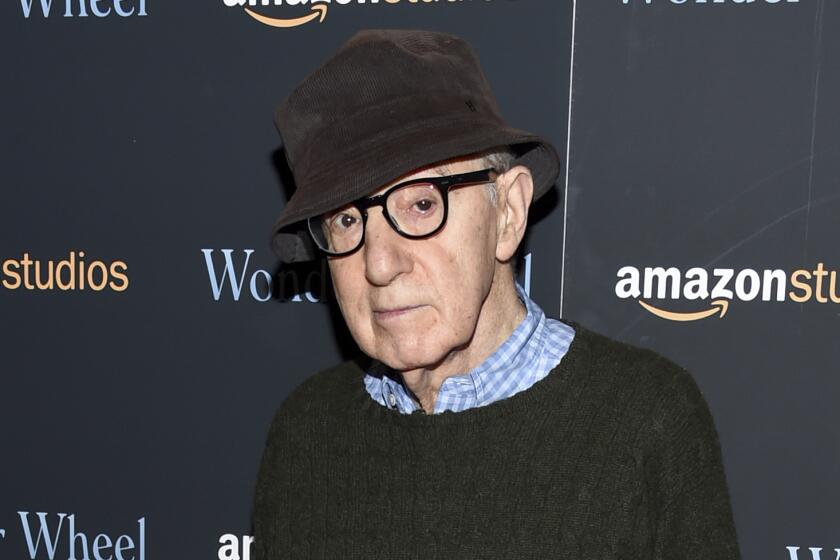

A year after an HBO documentary shed new light on sexual abuse allegations against Woody Allen, the director is releasing an essay collection.

Within hours, the Florida woman texted her friend that Emmett had offered her as much as $20,000 and said she would be reviewing a “legal document” from him regarding the payment the following day. He had already sent her “$3K for no reason a few minutes ago,” the Florida woman texted.

The Times could not determine whether Emmett or his associates made the payments to the Florida woman.

Hofmeister declined to answer The Times’ inquiries about this woman, who did not return requests for comment.

After this story was published, Hofmeister told Page Six: “As the Times acknowledged, there is zero proof that Randall paid her any money to sign an NDA. In fact, she said just the opposite.”

Roughly a week later, Kent subpoenaed the Florida woman in her custody battle with Emmett, requesting all text messages between the two. But, according to a Dec. 22 text to her friend, the Florida woman had “signed a[n] agreement” with Emmett saying she wouldn’t show any of her messages, in exchange for “a bunch of stuff from Randal,” she wrote.

A woman named Grace McCarthy also signed nondisclosure agreements with Emmett.

In May, The Times reviewed emails referencing payments from Emmett to McCarthy. She made various allegations about Emmett in an interview and said she had signed several NDAs at Emmett’s behest between 2015 and 2019. She sent two of these purported agreements to The Times, one for $2,700 and another for $7,500.

Asked to respond to McCarthy’s allegations, Emmett’s lawyer provided a declaration in which McCarthy retracted her statements to The Times, saying that she’d told “a bunch of lies to paint the worst possible picture of Randall.”

Emmett’s team also provided a sworn statement from one of McCarthy’s friends, Samantha Rakell, claiming that she too had lied to a Times reporter.

In McCarthy’s initial interview with The Times, she’d alleged that Emmett had mistreated Rakell.

“I want to tell the truth before my statements are published in the paper,” Rakell wrote in the declaration sent by Emmett’s team. “Because I allowed myself to be manipulated by Lala, I lied to Amy Kaufman to make Randall look abusive.”

But neither Kaufman nor any Times reporter had ever interviewed Rakell.

‘The Tasmanian devil’

Within his inner circle, Emmett commanded grudging respect. Some former subordinates marveled at his hustle and salesmanship. His partner, Furla, once described Emmett as “the Tasmanian devil.”

Working for Emmett had a certain Hollywood appeal — at first. The producer appeared to relish the role of the demanding boss who shouts to a harried assistant: “Get Ari Emanuel on the phone.”

But Emmett’s subordinates also found his behavior alarming. Former employees described him as emotional and volatile. Anna Szymanska, who worked as Emmett’s assistant for about a year before resigning in February, recalled an incident last year after she beat Emmett in a game of pingpong. Emmett threw the paddle so hard at a door in the office that the glass cracked.

“I was terrified, but I felt like I couldn’t show my fear because I had to be better than that,” said Szymanska, now 24. She provided The Times with a photo of the broken glass as well as a June 2021 invoice documenting a nearly $800 charge to replace it.

Hofmeister told The Times that “Randall never threw a paddle,” but then provided a sworn declaration from one of Emmett’s employees acknowledging the incident occurred. “Randall lost to Anna and threw a paddle. We were all laughing about it, including her,” Sean Stone, Emmett’s assistant-turned-executive, said in the document.

Hollywood assistants have launched a push against low pay. With the hashtag #PayUpHollywood, they are tweeting horror stories. But will the industry notice?

Numerous former assistants said Emmett demanded 24/7 assistance, frequently called them disparaging names and asked them to transport drugs, deliver payments to women and put large expenses on their personal credit cards.

Most of Emmett’s staff were men. Several assistants said they were instructed by Emmett’s former lieutenants to avoid selecting women for internships and other positions; one said the reason was “to protect them from Randall.” In the Wilshire Boulevard office, where framed photos of a nude Marilyn Monroe decorated the walls, “bro” culture prevailed, several assistants said.

Szymanska said in an interview that her boss told her he didn’t like working with women because he felt they weren’t “emotionally strong.” (Emmett denied the allegation.)

One night in July 2021, she said he summoned her to his house for an urgent errand around 10 p.m. His blood pressure was low, he said, and he needed coconut water and Muscle Milk to raise his sodium levels.

Drinks in tow, Szymanska arrived at Emmett’s house about an hour later to find her boss, fully visible through the glass entryway of his home, “lying naked on a couch.”

“I became extremely uncomfortable and disturbed,” she wrote in a declaration filed in the custody proceeding. “When I entered, Randall nonchalantly grabbed a pillow to cover his penis.”

Three months later, she recounted the experience over Facebook Messenger while venting about her job to a friend from her native Poland.

In the messages — which The Times translated from Polish — Szymanska wrote she had been harassed “sexually, mentally, physically and psychologically” during her six months on the job — including when she saw Emmett “lying on the couch naked.” She had also been subjected to seeing him urinate “with the door open” and “he has his back hair shaved in the office on the carpet,” she wrote in the message.

Hofmeister denied these allegations and said Emmett only urinated with the door open when taking a drug test, a requirement in the custody dispute, and “never intended anyone other than the drug tester to witness him in the bathroom.” She also questioned Szymanska’s credibility, citing a declaration the former assistant gave in support of Emmett’s custody request in January. Szymanska said she made the earlier declaration because Emmett was hounding her about it for months.

“I was scared about my immigration status, because I needed the job to keep my visa. So I felt obligated,” she said. “He gave me a talk where he told me what to say about what a good dad he was.” (Hofmeister said Emmett “did not pressure Anna or suggest topics to cover in her declaration.”)

Nearly three months later, after she left EFO, Szymanska provided a second declaration — this one in support of Kent — because she felt “compelled” to share her “concerns about what his children are exposed to when left with him for long periods of time.”

Several of Emmett’s former subordinates said they went into debt trying to placate the producer. He asked interns and assistants to cover his expenses — thousands of dollars in charges — with their own personal credit cards. (A person close to Emmett said that expenses incurred by assistants “for Randall’s personal life, in addition to corporate expenses,” were reimbursed.)

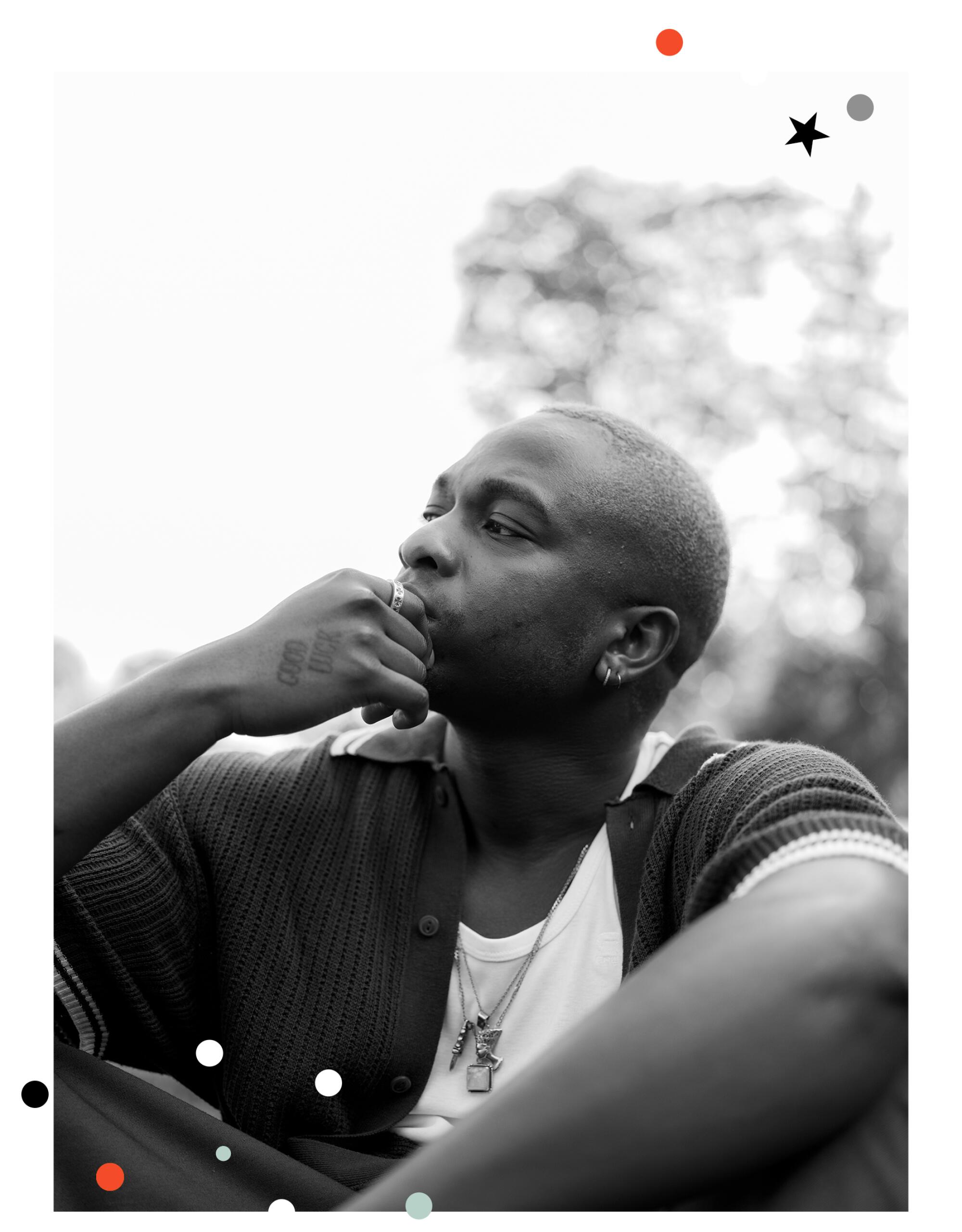

About a month into his job at EFO, Martin G’Blae was directed by an EFO executive to send Emmett’s poker chips and his custom poker table to Puerto Rico the following day, according to a text exchange reviewed by The Times. The table weighed 100 pounds, so G’Blae and an intern called FedEx Freight, and G’Blae put the $1,250 charge on his personal card. (The Times reviewed the receipt, bank charge and a photo of the package. A person close to Emmett said G’Blae was reimbursed.)

The former assistant said he then hopped on a flight to Puerto Rico to set up the table. Shortly after his arrival, Emmett sent G’Blae and another assistant to his $1,300-a-night suite at the Dorado Beach Ritz-Carlton to retrieve an item from the room’s safe. When the combination didn’t work, G’Blae said he summoned the hotel staff.

“A security team comes in and they open the safe and then they all just turn away,” G’Blae said. “I look in and see a big bag of cocaine.”

G’Blae was petrified by the prospect of being caught with drugs.

“I was in shock — and disbelief,” he said, noting that, as a Black man, he felt he was being put at an unacceptable risk. “We had a 30-minute car ride where I was constantly paranoid about getting pulled over by the cops.”

A second former assistant who accompanied G’Blae that night corroborated the account, saying the drugs looked “bricked up, like they were off a cocaine kilo.”

“I had seen Randall do lines off a poker table at Sundance [Film Festival] the month before,” this assistant said. “And while we were in Puerto Rico, Randall had me carry his drugs around in my sock during a night out and pull them out for him whenever we got to a casino. He offered me some, but I said no.”

Hofmeister declined to comment on the 2020 allegation or discuss alleged past drug use, but emphasized that Emmett has been sober since October 2021.

Entertainment industry assistants, who for decades have worked long hours with little pay, have in recent years demanded improved working conditions, inspiring a Twitter hashtag #PayUpHollywood.

The Times spoke with 10 former assistants; several said they were grappling with the lingering emotional toll of working for Emmett. Some said they’d experienced severe depression, prescription drug abuse and bouts of heavy drinking.

“Randall was different from being just a mean boss. He made people do dangerous things — and illegal things,” G’Blae said in May. “You had to be his punching bag — and his mule.”

G’Blae joined EFO in February 2020, when he was 26. He figured he would work hard for a year and earn a few movie credits, boosting his fledgling entertainment career.

Instead, throughout his nearly eight-month tenure, he said he was excoriated when Emmett’s 2018 Rolls-Royce got stolen, even though Emmett had instructed G’Blae to park the car on Mulholland Drive rather than in his driveway, according to text messages. He got blamed when Emmett’s goldfish died. (Text messages show G’Blae tried to explain that Emmett’s nanny said the fish was fine. “Don’t care,” Emmett texted back. “I told you to get doctor ... and now my fish is dead.”)

G’Blae also got chewed out for buying Emmett’s favorite daily treat — a $2.25 Toll House ice cream sandwich — in bulk from Costco rather than the convenience store next door. Emmett tossed one in the trash, saying it wasn’t “fresh.” A person close to Emmett denied these allegations, but a second assistant who was there confirmed the ice cream sandwich incident.

In June 2020, G’Blae was tasked with arranging a romantic stay for his boss and Kent at the Beverly Hills Hotel.

Emmett had asked him to decorate a suite with rose petals, so G’Blae rushed to a Melrose Avenue florist and spent $350 for two bags. Upon arrival at the hotel, a guest services manager let G’Blae into the room, which a second assistant had reserved. G’Blae sprinkled the petals around the room and used them to spell “L A L A” on the bed.

He left the room key with a concierge and went home. But when Emmett arrived at the hotel restaurant for a candlelit dinner with Kent, he texted G’Blae demanding the room key. G’Blae replied that it was at the front desk. “I can’t go to front desk,” Emmett texted. G’Blae headed back to the hotel, where staff members told him that Emmett needed to physically provide his credit card. After he relayed this information to Emmett, the producer responded:

“Stop … Dude my card is maxed,” Emmett responded. “Handle it.”

Forty minutes later, Emmett asked: “Martin where is the key?”

Fearing he might lose his job, G’Blae tried to put the charge — more than $1,200 — on his debit card. His bank rejected the transaction. So G’Blae called his mom and begged for money. His mother, Amy Kamara, said she was rattled by the call — it was nearly midnight in Rhode Island — but she quickly transferred the money into her son’s account because she feared he was in some danger. (The Times reviewed a copy of his debit charge rejection and the hotel invoice.)

A source close to Emmett said: “Martin knew he always had the option to contact George Furla to cover expenses, including Randall’s personal ones. Apparently Martin did not use this option.”

G’Blae, who left after working on “Midnight in the Switchgrass” in September 2020, said he has yet to be fully reimbursed for his expenses. By November 2021, after Hurricane Ida had damaged the roof of his family’s home in Rhode Island, and G’Blae needed money for repairs. He called EFO’s former bookkeeper and began liking a series of old text messages he’d sent about the charges to highlight what he believed he was still owed.

G’Blae didn’t realize that Emmett was also on the text thread. G’Blae sought reimbursement as Emmett was dealing with other issues: His former girlfriend, Kent, was demanding custody of their daughter; Allred was pressing for a settlement; and EFO’s bank accounts were frozen.

G’Blae’s phone lit up.

- Share via

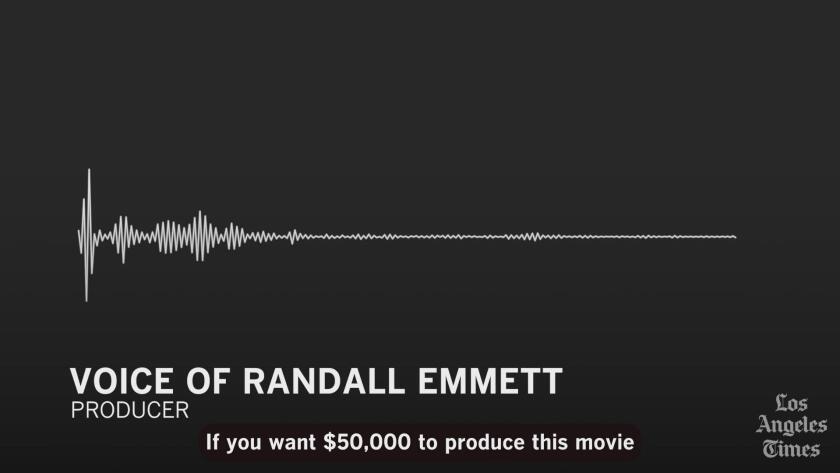

Voice notes from Randall Emmett to former assistant Martin G’Blae

“Martin, if you want $50,000 to produce this movie that starts next week, let me know,” he said in the first of four voice notes shared with The Times. “I’m just sad, man. I just really need somebody who could be a friend to me right now.”

Offended that Emmett was now calling him a friend, G’Blae declined the offer.

Hofmeister in a statement said that G’Blae “has only recently criticized Randall, despite previously speaking about him in glowing terms — even after leaving EFO.” G’Blae said he had been pleasant because he wanted to leave on good terms.

Several former assistants said they grew weary of the alleged abuse and Emmett’s semiregular threats of termination. “If you do that again, your fired,” read one typical text. Three former assistants said they also endured insulting remarks such as “you’re a moron,” “do something with the zits on your face,” “you’re f— lazy.”

While on location in Puerto Rico, another former assistant said he was ordered to book an inexpensive hotel room for Emmett and a female companion with his own credit card.

“The next morning, he had me go back to his actual room at the Ritz [Carlton], go into his safe and get $1,800 bucks for her,” the former assistant recalled. “You feel like you have to say ‘yes’ to everything he says.”

The subordinate delivered the payment but apparently made a math error, prompting an irate call from Emmett.

“He said I’d overpaid her by $200,” he recalled. “I said I was sorry, but he said I was fired, told me to get my stuff and find a flight home.”

Hofmeister said that Emmett “has never fired anyone for mistakenly overpaying a vendor, contractor or employee” and that it is “false and misleading to claim that verbally insulting his assistants is a common practice.”

The Times interviewed nearly two dozen Black entertainment industry voices, spanning directors, producers, writers, designers, agents and executives. They discussed racism in Hollywood, what needs to change and their frustration with years of talk and little action by powerful companies.

Several past assistants said they were also intimidated by the fact that Emmett had an LAPD officer working for him. In 2019, Emmett hired Eric Halem, a 34-year-old officer at the West Valley station, as a security consultant through a referral from “a member of a concierge company.” Though Halem described himself in a 2019 email as Emmett’s “business and security manager,” in an interview he said he never dealt with the producer’s business.

“I may have used that descriptor as a ruse or something,” Halem told The Times, adding that he obtained work permits for his consulting gigs through the LAPD. He said his responsibilities included running background checks through a private investigation firm, mediating disputes and responding to threatening parties. Once, he said, he also helped orchestrate the arrest of a man who was threatening Emmett with extortion. The man was later convicted.

Halem, for his part, described his interactions with Emmett’s staff as “positive.”

“I never introduce myself to anyone as a LAPD officer. I always introduce myself as a security consultant,” said Halem, who appeared in small roles in “Vanderpump Rules” and “Midnight in the Switchgrass.”

In January 2020, Halem sent an invoice to Emmett noting that he was to receive a $1,000 tip, “per Randall,” for a “TMZ video.” Asked what the video entailed, Halem responded: “I have a lot of clients. I don’t recall the specific incident.”

Steve Small, a longtime agent and business affairs executive, joined Emmett’s operation last August after knowing the producer for 20 years. In an interview, Small disputed allegations of an abusive environment, saying that he “never saw any unprofessional behavior.”

In a separate statement, Small, who now serves as film and television president of Emmett’s new company, Convergence Entertainment, said, “During my tenure with the company I have never witnessed any verbal insults from Randall to any employees.”

He said Emmett and Furla have filled a niche in Hollywood by providing opportunities for aging stars and movies for their fans.

“Randall and George are trying to create an opportunity for artists and content creators — actors, writers and directors — in a very challenging environment for independent filmmakers,” Small said. “And I give these guys credit for that.”

Emmett and Furla’s business model relied heavily on tax credits and paying millions to aging stars and then pushing their films in foreign markets including the Middle East, Russia and Turkey, where audiences remained eager to see American he-men smash bad guys. The bigger the name, the bigger the foreign presales, which meant more investment and more money that everyone — actors, agents and producers — could grab.

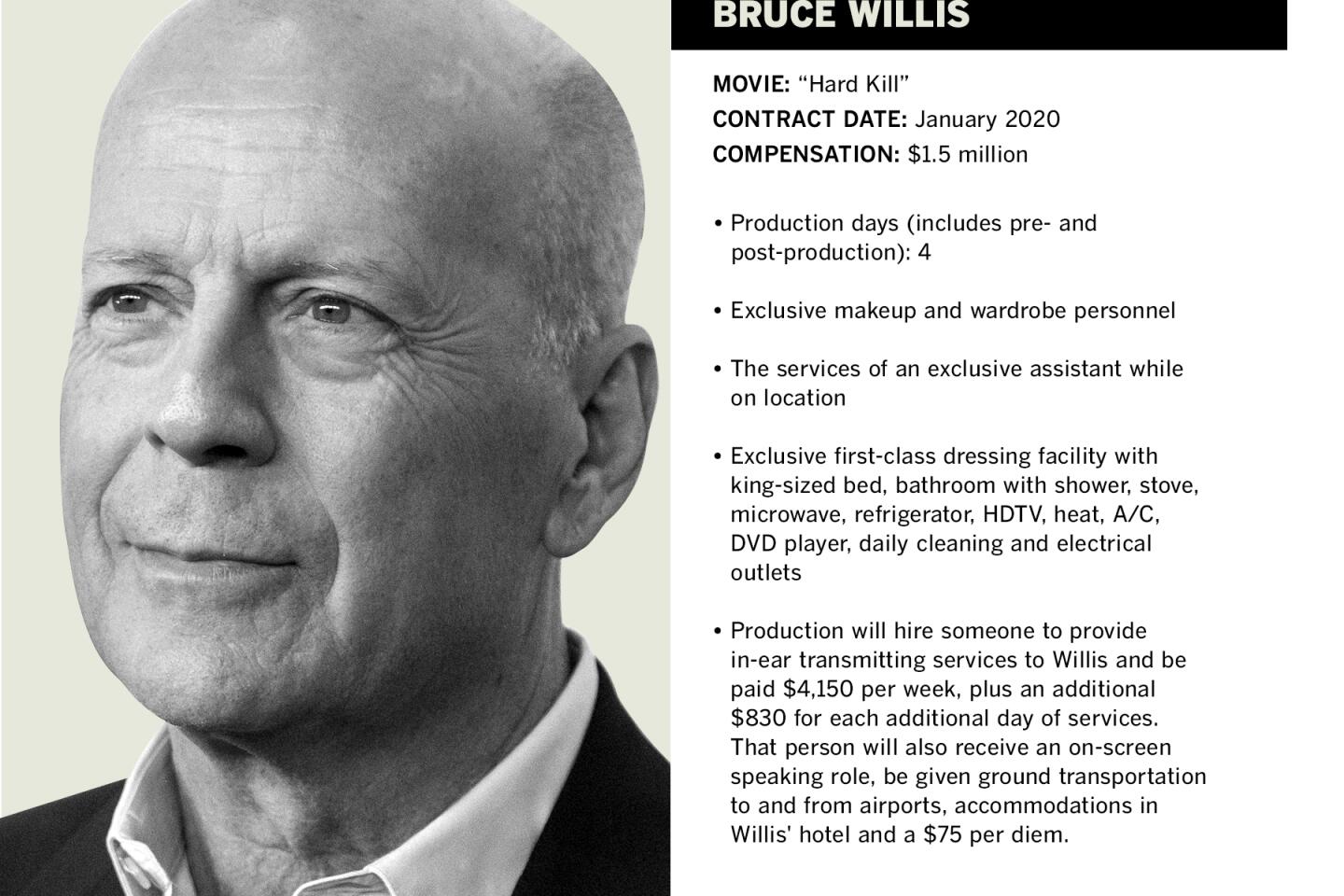

According to internal emails, Willis’ standard fee was $2 million for two days’ work.

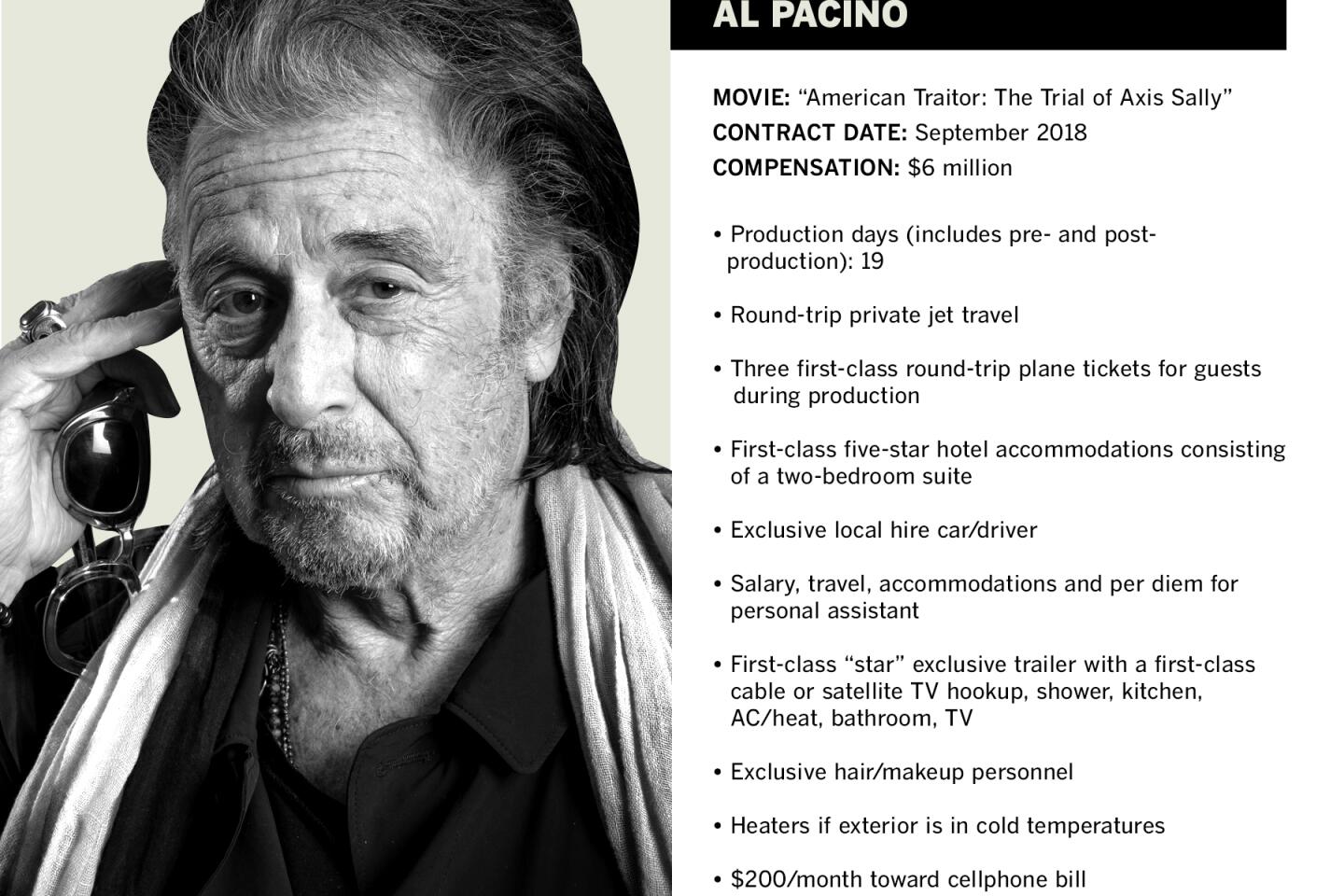

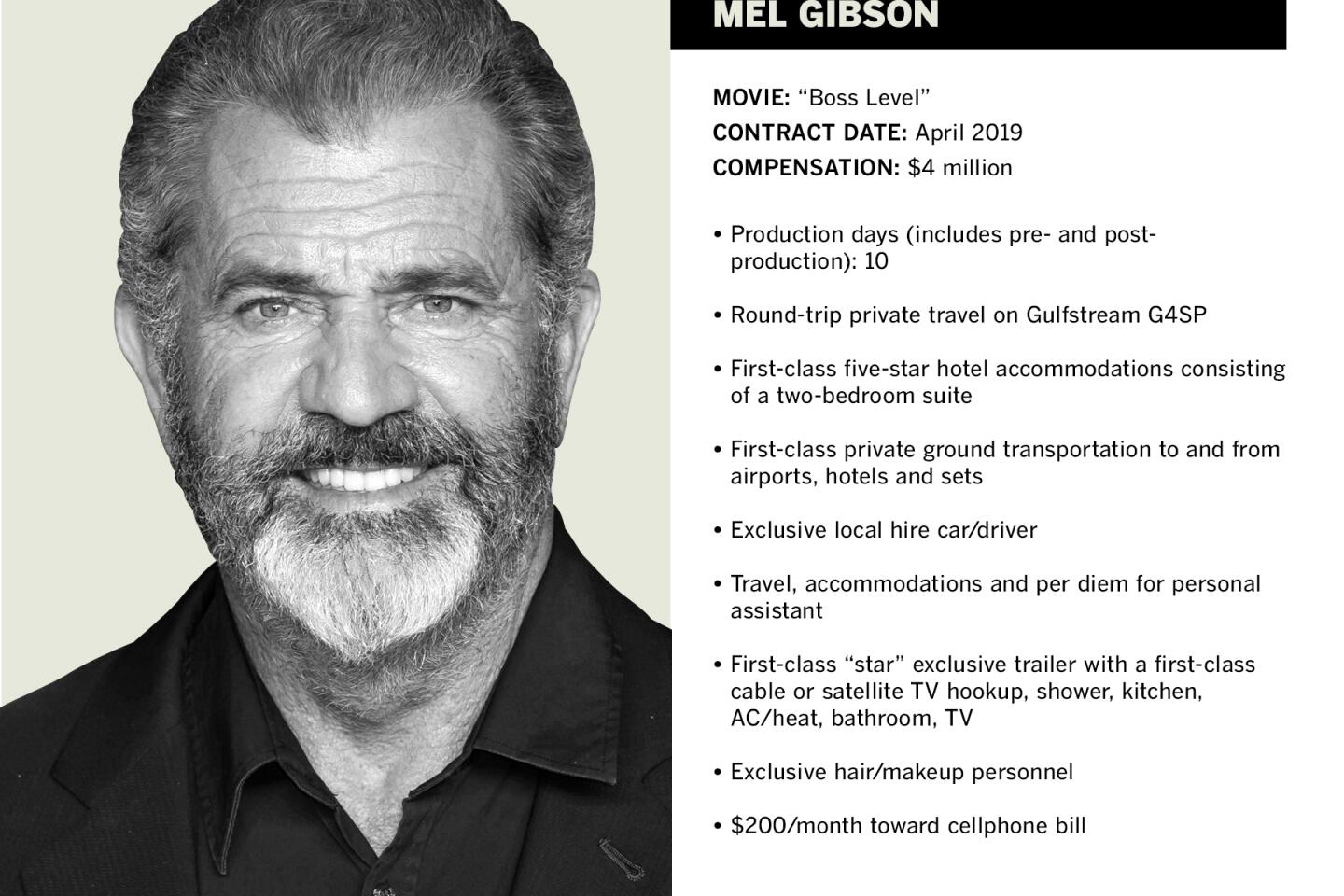

Actors’ contract details:

Other actors demanded even more, amounts that though not unheard of, were unusually high, according to Hollywood veterans.

Al Pacino reaped $6 million for working up to 19 production days on “American Traitor: The Trial of Axis Sally” in September 2018. Gibson was paid $2 million the following year to act for 10 days in “Force of Nature” and $2 million more to serve as its executive producer, according to internal documents. In August 2020, Stallone’s agent at Creative Artists Agency wrote an email to Emmett approving “the proposed $8M for four days of work” on an undisclosed project. Through their publicists, Pacino, Gibson and Stallone declined to comment.

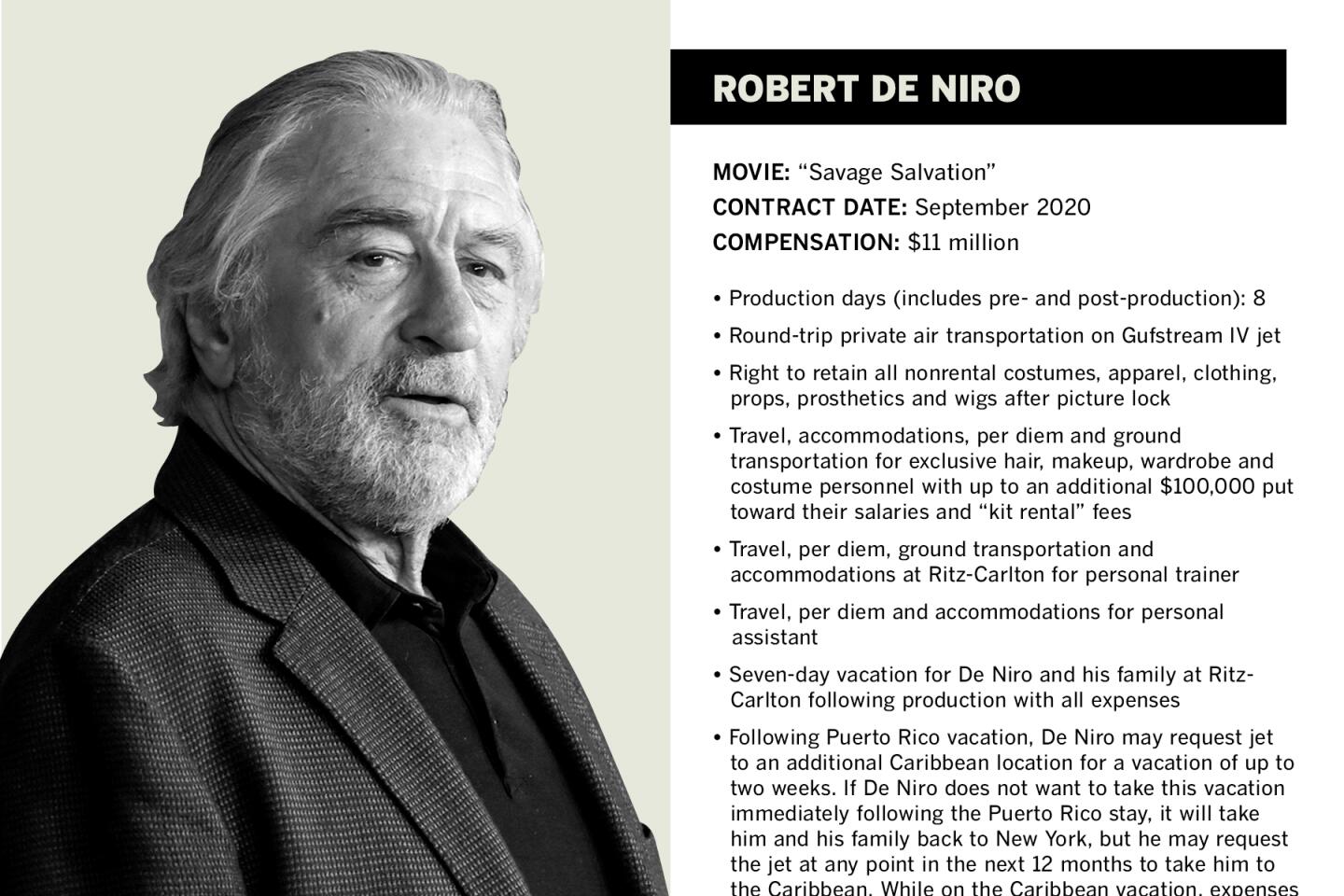

These actors’ deals included private plane travel, five-star hotel accommodations, a trailer, personal drivers, assistants, their choice of hair and makeup artists and on-set security. Robert De Niro’s deal stood apart.

The 78-year-old “Taxi Driver” star demanded $11 million to spend a week in Puerto Rico early last year to film “Savage Salvation,” an Emmett-helmed film about a recovering opioid junkie seeking revenge.

Fees for De Niro, who played a tough cop, ate up half the film’s budget. De Niro’s deal, reviewed by The Times, also included an all-expenses-paid weeklong vacation for his family at Dorado Beach, a Ritz-Carlton Reserve. And, if De Niro wanted, EFO was to have the Gulfstream IV jet whisk him and his family off to “an additional Caribbean location for an additional vacation up to two weeks.” The family’s expenses, up to $100,000, would be paid by EFO. De Niro’s publicist said the actor had no comment.

De Niro’s talent agency, CAA, has long embraced Emmett and Furla. Most of the top talent in EFO movies, including Willis, were represented by CAA, which declined comment.

EFO made hefty payments to actors even as it struggled to meet payroll and pay for crew meals and other costs on location, according to three film crew members.

The investors

Wealthy investors eager to play in Hollywood were attracted by Emmett’s list of film credits and proximity to power.

EFO’s financiers over the years have been an eclectic mix. They included film studio Lionsgate and two London film financing groups, Ingenious Media and the Fyzz Facility. A decade ago, investors with ties to the Russian oil industry provided tens of millions of dollars for Emmett’s films.

Internal records show that Emmett also turned to multimillionaires outside of the entertainment world, including Jacksonville, Fla., entrepreneur Thomas M. Leonard; a former Hollywood tequila bar owner/real estate investor/filmmaker, Ted Fox; grandson of the late billionaire founder of Conair Corp. and actor Sergio Rizzuto; and, until about 2015, the head of an Atlanta-area healthcare staffing firm, Richard L. Jackson.

In recent years, Emmett’s most generous investor has been Meadow Williams, an actress who primarily had small parts in shows like “Murder, She Wrote,” until she became romantically involved with the founder of Nature’s Plus vitamins, Gerald Kessler.

Williams, who inherited a reported $800 million when her 80-year-old husband Kessler died in 2015, has invested heavily in Emmett’s projects.

Both she and her boyfriend, Swen Temmel, typically would be assured roles in the film projects she helped to finance, according to contracts reviewed by The Times. Williams did not respond to requests for comment.

Williams also allowed Emmett to shoot films on her 554-acre ranch near Santa Ynez, the former retreat of McDonald’s founder Ray Kroc.

In turn, Emmett and Furla tried to give their wealthy benefactor the star treatment, allowing Williams to pursue her acting dreams. She starred in the Emmett- and Furla-produced “American Traitor: The Trial of Axis Sally,” a story about a U.S.-born broadcaster who dished Nazi propaganda in Germany during World War II.

Williams invested $9 million in the project, according to internal documents; much of it went toward securing Pacino as her co-star.

But the veteran actor had some qualms, according to an email he wrote to Emmett in June 2019. After shooting wrapped on the $18-million film, Pacino complained that Williams was interfering with director Michael Polish’s creative process.

Emmett insisted that Williams needed to have “her voice heard” because “she wrote the check.”

Pacino countered. “My thought Randall is very simple. She is not a professional. ... Someone has to say back off a second dear, we’re completing the film still, take a look when it’s ready,” according to a 2019 email.

The actor suggested adding another shooting day “to help [Williams] give a better performance.”

“Let’s do this Randall. I’m not going for the A’s or the B’s. I’m going for something between C and B,” Pacino wrote to Emmett. “I don’t like Ds. And, as long as you put the effort in with what you know about filmmaking and Michael too I’m sure we’ll get to a B-. And that’s good enough for me, if it’s good enough for you.”

Pacino’s publicist said the actor had no comment. “Randall would never comment on his personal interactions with his actors,” Hofmeister said.

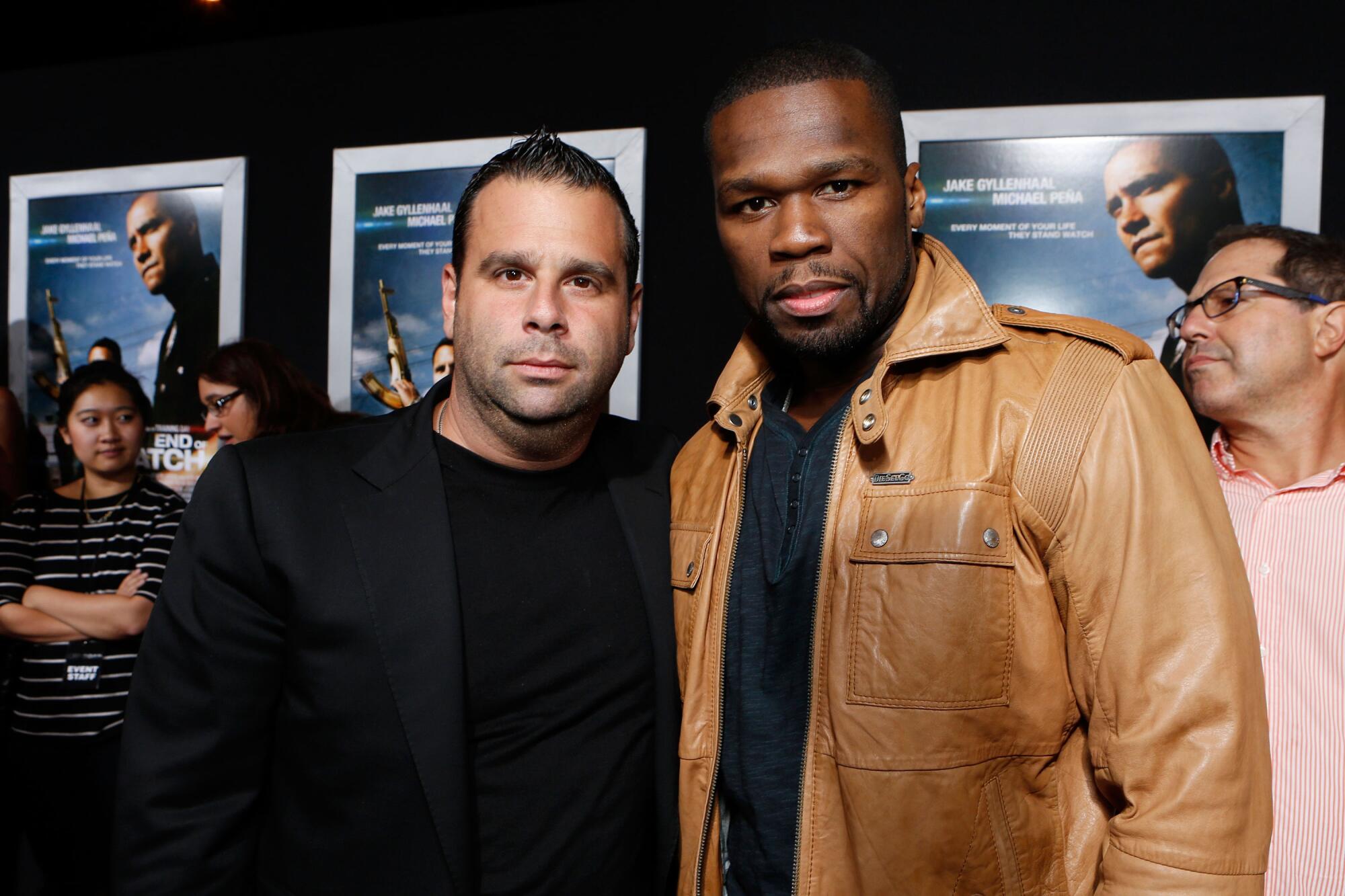

Another longtime business partner of Emmett’s, 50 Cent, turned on him in April 2019.

Emmett and Jackson’s relationship went back to 2008, when the producer put the performer in the 2008 film “Righteous Kill” with De Niro and Pacino. The two formed their own production company, Cheetah Vision, and in 2014 became producers on “Power.”

But in April 2019, Jackson announced on Instagram that Emmett had owed him $1 million and mocked his relationship with then-fiancee Kent. “Money by Monday Randall,” Jackson demanded on Instagram.

Emmett pleaded for Jackson’s mocking posts to stop, but mistakenly called him “Fofty” instead of “Fifty.” Jackson just posted Emmett’s texts.

The feud ended a few days later as a result of a settlement agreement, which was reviewed by The Times. Jackson agreed to delete the negative remarks and Emmett had to post a public apology, which also noted that Emmett had paid the debt.

Emmett was required to stay clear of Jackson on a different Starz crime drama the pair produced, “BMF: Black Mafia Family.” The agreement did permit Emmett to attend the show’s red carpet premiere, as long as he remained 100 feet from Jackson and refrained from joining group photos.

Through his publicist, Jackson declined to comment; Hofmeister said Emmett would not “discuss the business matters of others.”

Months later, Emmett learned “Vanderpump Rules” cast members talked about the “Fofty” dust-up during the show’s taping. Emmett reached out to Ron Meyer, then-vice chairman of NBCUniversal, which owns “Vanderpump” network Bravo, and begged him to quash the segment.

“If they mention him anywhere in this show … the antics will start Again which could Destroy my career,” Emmett wrote in an October 2019 email.

In exchange for the favor, Emmett told Meyer he would thank him “for real” from the Oscars stage if “The Irishman” won best picture. Soon, Meyer’s assistant sent an email, saying, “Ron would like to get” six tickets reserved for the Scorsese film’s premiere. Two were for his neighbor, and the rest were for private detective Anthony Pellicano. Emmett and Meyer declined to comment.

Clashes over money

Emmett’s career seemed to be soaring in 2019.

That fall, Netflix was releasing “The Irishman.” And Emmett was swinging for the fences with his production of a $45-million time travel movie with Gibson and Frank Grillo called “Boss Level.” He was also putting together a TV series based on Schwarzenegger’s early years in Venice Beach. “The Terminator” himself was expected to have an on-screen role in “Pump.”

But that spring, the facade began to crumble.

On March 9, 2019, Emmett and Furla received an email from a key financier with the subject line: “Debts.”

In the email, the British executive wrote that EFO owed: “TOTAL $8,250,000 PLUS INTEREST. This is a serious amount of capital … I get calls every day from my investors on most of these loans … What’s the plan?” (A person close to the matter said much of the loan had been repaid.)

That October, additional financiers turned up the heat.

Charles Auty, managing director of the Fyzz Facility — a group of wealthy British financiers who once lent money freely to EFO — had learned Emmett was coming to London for “The Irishman” premiere. He suggested a meeting, but Emmett initially balked.

In an Oct. 10, 2019, email, Auty warned that Emmett risked sending “a very dismissive and negative message to all of our investors to whom you guys owe in excess of $30 million in principal alone.” Emmett needed to show up, Auty said in a follow-up email, “to let the investor see you’re there grinding away getting movies made.” (Emmett met with the financiers, emails show. A person close to Emmett said his firm currently owes about $17 million in loan principal.)

Auty declined to comment.

Fyzz Facility in May sued in Los Angeles County Superior Court for $10 million, alleging that Emmett and Furla used its funds without authorization, including allowing CAA to transfer $1.25 million from the loan advance without Fyzz’s approval, to actor Gerard Butler’s company for a movie, “Mexicali.” But the film has not been made, and Emmett declined to comment.

EFO has yet to file a response to the suit.

Also in the fall of 2019, the Schwarzenegger project, “Pump,” was deflating.

Emmett had hired four guild writers that year to develop scripts for a TV series loosely based on Schwarzenegger’s early years in California, according to internal emails and interviews. Writers said they envisioned “Pump” as a love letter to Venice Beach in the early 1970s and the birth of the modern bodybuilding culture. In a September 2019 meeting that included the writers and Schwarzenegger, the former California governor seemed enthusiastic. “Pump” would showcase his immigrant story.

Huang, one of the writers, recalled a separate September 2019 pitch session with producers. “We do the pitch and Randall loves it. He’s … clapping and cheering the whole time. He was like, yeah, this is great. Now we can get Arnold on board.’”

Huang was stunned: “That was when we learned that Arnold hadn’t signed anything.”

The writers said they previously had been told that Schwarzenegger and Emmett were producing the series, and that Emmett would shop it to a streaming service. That seemed odd, Huang said, because producers typically line up agreements and a buyer before producing episodes “because it’s so expensive to make television.”

But, Huang said, “we were told Randall has these investors who just write him checks.”

James van der Woerd had provided a $750,000 loan for “Pump” in August 2019. A lawsuit brought by his Canadian firm, 902878 Ontario Ltd., alleges that Emmett assured him that Schwarzenegger was committed to the project and that his money would go toward the actor’s fees and to hire writers.

Van der Woerd didn’t see his money again, according to his civil fraud and breach of contract lawsuit seeking $1 million. The loan was “used by defendants to pay themselves exorbitant producer fees,” the suit alleges. Van der Woerd declined to comment. Emmett declined to comment but disputes the claims.

By mid-October, writers and insiders felt the project was probably doomed when they learned Schwarzenegger had switched to United Talent Agency from CAA, which declined to comment. Martin Singer, a Schwarzenegger attorney, said the star had bowed out due to “scheduling problems.”

That November, payments to the writers stopped. One of the writers, Patrick Moss, camped out in the lobby of Emmett’s Wilshire Boulevard building until one of Emmett’s lieutenants, Tim Sullivan, brought down a check.

But finances were tight.

“We’re short about $14,000,” Sullivan wrote in a group email Nov. 22, 2019. “I’ll put in 7 k george can put in 7 k,” Emmett replied. But Furla disagreed: “Not my account. I just wired money to pay efo salaries.”

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit in March 2020, the writers still hadn’t been fully paid, nor had EFO made contributions to WGA West’s health and pension fund.

“Here we were, sitting in the middle of the pandemic,” Moss said. “The message that [Emmett] was sending was that my family and my kids didn’t matter.”

The WGA West filed for arbitration and advised its 10,000 members against working with EFO. The guild won an arbitration award against the firm that, with interest, now exceeds $588,000.

“They have not paid a cent ... And on Instagram, you see that Randall leads this lavish lifestyle — flying in private jets, going to pickleball tournaments at La Quinta and constantly staying at these lavish resorts.”

— WGA West attorney Leila Azari

“They have not paid a cent,” said WGA West attorney Leila Azari. “And on Instagram, you see that Randall leads this lavish lifestyle — flying in private jets, going to pickleball tournaments at La Quinta and constantly staying at these lavish resorts.”

A person close to Emmett said EFO’s attempts to settle with a payment plan had not succeeded. Azari said the attempts were “nothing more than bad faith legal maneuvers to try and evade” the ruling against them.

Since 2010, more than 30 lawsuits have been filed against Emmett and Furla, and a half-dozen more against Emmett. American Express sued Emmett for $393,756; the case was settled with a payment plan, court records show. Last year, Emmett repaid nearly $400,000 in debt to the IRS.

Financiers and fellow producers have hit Emmett and Furla with a barrage of lawsuits that allege fraud, misrepresentation, breach of contract and personal enrichment at the expense of others. Emmett and Furla, who dispute the allegations, declined to comment on pending litigation.

Two lawsuits have raised concerns about the partners paying themselves excessive fees, including on projects that were abandoned. (Company records show that Emmett’s fees in recent years were as high as $1.2 million a film.) Loans made to Emmett and Furla “were not utilized for their intended purpose,” according to a February lawsuit filed by European banker Arnaud Lannic, one of the Fyzz Facility investors.

Lannic’s investment firm, Shiny River, provided more than $7 million in loans from 2015 through mid-2016 in part to finance seven movies, but half of those projects were never made. (With interest, Lannic’s attorney said, the debt at issue in the pending lawsuit now exceeds $14 million.)

Rather than investing in their business, Emmett and Furla paid themselves rich producer fees to “meet their extravagant living expenses,” Shiny River alleged in the suit. Lannic, through his attorney, declined to comment.

The Shiny River suit also said that during a 2018 meeting at the Four Seasons Hotel in New York, Furla led Fyzz investors to believe that EFO was good for the money and its film library was worth around $9.6 million.

But, since then, an appraiser hired by Lannic “concluded that the EFO film library is worth, at best, only $2.1 million.”

Emmett and Furla declined to comment on Lannic’s lawsuit.

Two years ago, Emmett and Furla began hunting for new partners and engaged in preliminary sales talks with Lionsgate, their longtime distribution partner. But the deal, referred to internally as “Project X,” never materialized.

Soon, the pair thought they’d found a new financial savior — New York investment firm Forest Road. An internal 2020 deal memo, reviewed by The Times, showed the firm considered paying $12 million for preferred EFO shares. But Forest Road, which declined to comment, withdrew.

By mid-2021, EFO was teetering. Filmmaking costs had soared due to the pandemic.

The producers moved out of their Wilshire Boulevard offices, leaving a debt of $336,000 in unpaid rent, parking and phone fees, according to an October lawsuit. (The landlord’s attorney declined to comment.) “We fail to see how Randall’s dispute differs from the numerous lease disputes resulting from Covid,” Hofmeister said.

Meanwhile, a Beverly Hills entrepreneur, filmmaker and investor, Jonathan Baker, was still steamed that Emmett allegedly reneged on a 2015 agreement for a two-picture deal. They made one film “Inconceivable,” starring Nicolas Cage, which Baker directed, but their dealings soured. Baker sued in 2017 to try to get his $1-million investment back and reluctantly agreed to a $640,000 settlement.

But Emmett and Furla paid only a fraction of that amount, and in December 2020 L.A. County Superior Court Judge Craig D. Karlan ordered them to pay $570,855, according to a judgment. A person close to Emmett and Furla disputed Baker’s allegations and said negotiations have been complicated by Baker’s desire to include production of a second film in any resolution. Baker said they wanted him to first invest an additional $1 million.

“Randy and George prey on people with empty promises and they have only one thing in mind: Extract millions upon millions of dollars only to be told you will never work in this town again if you stand up to them,” Baker said.

In March 2021, Baker’s attorney, Joseph Kar, won a court order to freeze the EFO bank accounts. But just before the freeze went into effect, Furla withdrew $125,090 from the company’s accounts, according to court testimony.

“That’s problematic to say the least,” Karlan said at a hearing this year. Furla had told Kar during a court-ordered examination that he had been unaware the freeze was imminent. “When money comes in, why should it just sit there?” Furla asked. (He declined to comment.)

When finances were tight, Szymanska said she often heard Emmett and Furla discussing making “another bull— Bruce Willis movie.” Emmett denies that he made such remarks, Hofmeister said.

One of the last films the company made with the actor was “Wrong Place,” for which Willis spent two days on set in Alabama. His two associates — his producing partner, Stephen J. Eads, and Adam Huel Potter, who fed lines to Willis through an earpiece — guided him.

“He was never alone,” said Szymanska, who spent time on location. “When nobody from Bruce’s team was around, the crew would say how sad we were to see him in this state.”

Five months later, the actor’s family would disclose his aphasia diagnosis.

Eads and Potter did not respond to questions from The Times about their work with Willis. The actor’s attorney, Singer, said that his client relying on Eads and others was similar to “Stevie Wonder having an assistant lead him on stage to perform, or Marlee Matlin’s reliance on a sign language interpreter[.] My client allegedly relying on Stephen Eads or others to provide certain assistance is in the same vein. ... It ought to be commended.”

Emmett was barely on the “Wrong Place” set, according to crew members. After a brief appearance, he traveled from Birmingham, Ala., to Nashville, where onlookers would snap those now-infamous pictures of him out on the town with women who were not his fiancee. On Oct. 27, 12 days after the images surfaced, Kent moved out of the house on Mulholland Drive, her 7-month-old daughter in her arms.

As his custody battle began, Emmett continued to fight Baker’s claims in court. In a hearing in late May, A. Raymond Hamrick III, a longtime lawyer for Furla and Emmett, rejected allegations that the pair had created a web of limited liability shell companies to shield themselves and their film titles from creditors.

“This was not a shell. This was an active company [but] COVID gutted them,” Hamrick told the judge. “They couldn’t produce for two years because of COVID.”

But the pair filmed at least eight movies during the pandemic, including “Wrong Place.”

Baker’s attorney, Kar, has continued to press his case that Emmett and Furla should be held personally liable for their debt.

“The company doesn’t exist anymore,” Emmett told Kar in a late April deposition. “There’s no employees, there’s no money for overhead, there’s no money — you know, we got hit really bad in COVID and had substantial overages on movies and liabilities the company has taken on and just couldn’t survive anymore.”

Emmett said he had “resigned” from EFO to start a new venture: a new company called Convergence Entertainment. Emmett put his Mulholland Drive home on the market in May for $6.3 million. He also moved back into his old Wilshire Boulevard office building — despite the litigation over unpaid rent.

“I just wanted office space … to be able to get jobs as a director,” Emmett told Kar. “That’s what I’m focused on now.”

On Friday Emmett wrapped production on the Georgia set of a new bank heist movie called “Cash Out.”

It stars John Travolta.

Times staff researchers Scott Wilson and Cary Schneider contributed to this report. Elizabeth Kanski provided translation assistance.

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Credits

Investigations editor: Richard Verrier

Deputy managing editor, entertainment and strategy: Julia Turner

Culture columnist and critic: Mary McNamara

Design director: Taylor Le

Art direction and design: Jim Cooke and Jan Molen

Illustrator: Lizzie Gill

Copy editor: Angela Jamison

Director of photography: Kate Kuo

Photo editors: Jacob Moscovitch, Jerome Adamstein and Taylor Arthur

Digital production: Jevon Phillips

Video: Diego Medrano

Social Media: David Viramontes

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.