What are the Oscars for? Hollywood grapples with awards season anxiety

- Share via

To filmmakers who grew up watching the Oscars, this Sunday is supposed to be their Super Bowl. With its parade of fashion, movie stars and acclaimed films, the annual awards show, which once brought in tens of millions of viewers, inspired generations of artists to get into the business.

But as television ratings have shrunk and movies have been demoted to a supporting role in pop culture, many people in the industry worry that the glamour of honoring the top achievements in filmmaking has faded.

There’s a growing worry that the Academy Awards have become a niche for a passionate crowd as audiences gravitate toward star-studded TV series, video games and TikTok influencers. That, some say, has created an identity crisis for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the group that votes on the awards.

The academy’s mission has always been twofold: to promote the business of moviegoing while also honoring the highest achievements in the art form. But it has become harder for the Oscars to deliver on that promise when general audiences respond with a shrug and as the definition of moviegoing evolves amid the rapid shift to streaming.

Cutting important categories from its live telecast and Twitter-sourcing fan favorites won’t do a beleaguered motion picture academy any favors.

“The film business is at a particularly strange state right now,” said Peter Newman, who produced the Oscar-nominated 2005 film “The Squid and the Whale” and runs the dual MBA/MFA graduate program at New York University‘s Tisch School of the Arts and Stern School of Business. “Clearly, saluting the best movies and the best performances doesn’t necessarily make for required viewing at the moment.”

The Oscars face a litany of problems, some of which are out of the organization’s control and others that are self-inflicted. Those include the unpopularity of the nominees, the fragmentation of the TV audience and the controversial pared broadcast presence of eight awards, meant to preserve ratings but which has alienated craftspeople the Oscars are supposed to celebrate.

A major source of anxiety is that relatively few people have seen or heard of the movies that are most expected to win the main statuettes.

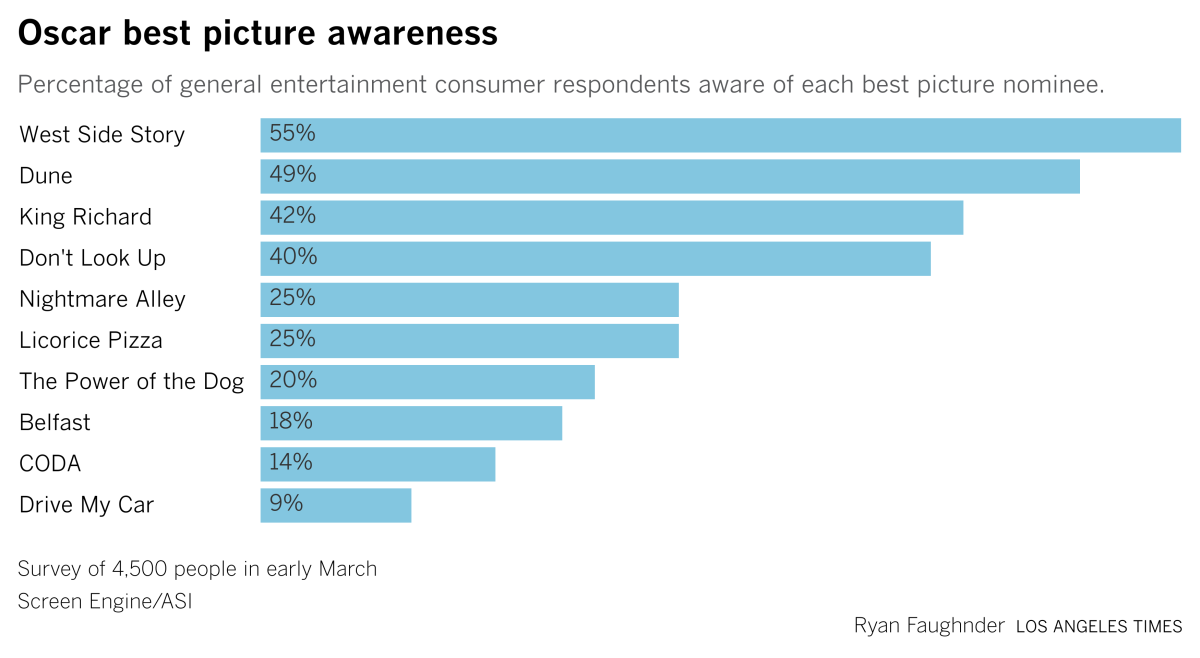

An early March survey of 4,500 entertainment consumers found that nine of the 10 best picture nominees had less than 50% awareness among respondents. The front-runners did not fare well. According to Screen Engine/ASI, 20% of people were aware of Netflix’s “The Power of the Dog” and 14% knew of Apple’s “CODA.”

That’s a problem for the academy, which is under pressure from Walt Disney Co.-owned ABC to improve viewership. Last year’s Academy Awards, when “Nomadland” won the most coveted prize, drew a record low of 10.4 million viewers.

The lone film approaching traditional blockbuster status among the best picture nominees is Denis Villeneuve’s “Dune,” which grossed about $400 million in worldwide box office receipts and is nominated for 10 awards. Netflix’s apocalyptic comedy “Don’t Look Up,” starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence, was also widely seen, driving 360 million viewing hours in its first four weeks of release, according to the streaming service.

This year’s nominees are more popular than last year’s. But awareness is still low for the majority of the best picture picks.

“The first question you have to ask is, ‘Who’s it really for?’” said a veteran film executive who requested anonymity to protect relationships. “You can’t say it’s for the public when you honor movies the audience hasn’t seen and doesn’t care about.”

The academy originated in 1927, blending art and commerce, and not in that order. MGM topper Louis B. Mayer came up with the idea for the academy as a way to thwart labor disputes and burnish Hollywood’s image. They became a massive promotional vehicle for the movie industry and one of the biggest shows on television.

It was during the glory days that watching the Oscars helped inspire former academy President Sid Ganis, known for producing “Akeelah and the Bee” and “Big Daddy,” to get into show business. Ganis recognizes the modern challenges but said the academy’s sense of purpose is unchanged. Moreover, the show is necessary, he said.

“The Oscar brand shouldn’t go away,” Ganis said in an interview. “We need it as a symbol of who we are as a society, who we are as a culture. And we also need it to do what its job is, which is to promote filmgoing. And, yes, what that means is a little less defined these days. But if you ask anybody involved with the Oscars, they’ll say, ‘Go to the movies.’”

As the Oscars hope to stem a ratings slide, producer Will Packer discusses the controversy over this year’s changes to the show and what viewers can expect.

The value of an Oscar has changed over the years. Winning the gold-plated trophy was once a way for movies to get a huge bump at the box office and on home video, a strategy Harvey Weinstein perfected with films like “Shakespeare in Love.” Winning an Oscar remains a lifetime goal and the ultimate résumé booster for actors, directors, hairstylists and composers.

These days, though, box office is far less of a factor. Three of the best picture nominees — “The Power of the Dog,” “Don’t Look Up” and “CODA” — were released by streaming services. “Dune” and “King Richard” hit theaters and streamer HBO Max simultaneously months ago and have effectively ended their theatrical runs.

“You might say the academy has kind of lost its original purpose in the studio era, because there just aren’t that many films in theaters,” said Jonathan Kuntz, a film historian at UCLA’s School of Theater, Film and Television.

Yet studios still drop big bucks on awards campaigns. A full-blown run at the top prize might cost a studio $10 million to $15 million in spending on TV ads, billboards, newspaper spreads and other trappings of Oscar season. Some have spent much more. Netflix deployed at least $25 million to promote its 2019 candidate “Roma,” according to people familiar with the matter. “For your consideration” ads for “The Power of the Dog,” “CODA” and “Belfast” have inundated social media and print publications in recent weeks.

There was a time when a best picture Oscar meant everything to studios.

What’s the benefit? For Netflix and Apple, it’s not about the commercial performance or value of the movies in their libraries. Instead, those companies are motivated to earn the respect of the town, secure bragging rights and prove to skeptical filmmakers and rivals that they are legitimate forces in film. Plus, as tech giants, they can afford it.

“It’s a PR move for the companies,” Newman said. “The film industry is one of the few industries where vanity is a tradable commodity.”

Getting into the Oscar conversation is one of the few ways indie titles, festival favorites, international films and documentaries can find a mass audience. Take Ryûsuke Hamaguchi’s “Drive My Car,” a languorous, Chekhov-infused Japanese film that is nominated for best picture. Or even “Parallel Mothers,” Pedro Almodóvar’s Spanish-language drama nominated for lead actress (Penélope Cruz) and original score (Alberto Iglesias).

“If you’re in the Oscars, you’re on the map,” Sony Pictures Classics Co-President Tom Bernard told The Times in January. “Right now, the Oscar movies are the ones that have that awareness, and people seem to step out to the theaters for them and pay $20 for pay-per-view.”

Analysts have said that nominating more commercial fare would keep the show relevant. Campaigns for “Spider-Man: No Way Home,” “No Time to Die” and “House of Gucci” ultimately sputtered. Still, why not nominate Disney’s popular phenomenon “Encanto” for best picture, rather than just in the animation and music categories?

It’s not clear that simply honoring more blockbusters would save the show, though. The decline of the Oscars ratings has followed the overall trend of eroding viewership afflicting live television broadcasts, with the exception of National Football League games.

Social media has been particularly brutal for awards season. The Oscars used to be one of the few times viewers could see a moving Tom Hanks speech and watch the world’s biggest stars swish down the red carpet in designer gowns. Now, stars seem to be available everywhere and all of the time. Anyone who cares about the fashion can find the highlights online later.

Seeking to attract a wider audience, the group has changed the show in ways that smell of desperation to Oscar purists.

Artisan guilds and filmmakers balked at the academy’s decision to pre-tape eight award categories, including original score and film editing, to limit the run time to three hours. More than 70 prominent film professionals — including Oscar winners James Cameron, Kathleen Kennedy and Guillermo del Toro — issued a letter saying the plan would reduce some nominees to “second-class citizens.”

The telecast this year will bestow a “fan favorite” award (though not an official Oscar) based on polling from Twitter and a dedicated website. The hope was that the award would be a way to recognize a hit like “Spider-Man: No Way Home.” But the plan raised the specter of the masses instead choosing something like the critically reviled Camila Cabello musical “Cinderella.”

Oscars producer Will Packer has made no apologies for his efforts to juice ratings by making the broadcast more entertaining.

“I think you have to be really honest and aware of the time in which we’re living, and say: ‘How can we make the best version of a show in today’s environment?’” the “Girls Trip” and “Ride Along” producer told The Times recently.

Ganis is familiar with the kind of blowback Packer and the academy have received. In 2009, the last year of Ganis’ tenure as president, the academy expanded the best picture field from five nominees to 10 after failing to honor Christopher Nolan’s “The Dark Knight.” The tactic was blasted for diluting the prestige of the nominations.

Now with more slots available, it’s easier for studio films such as “Dune” to break in. Yet the odds are also higher that festival darlings like “Drive My Car” and “CODA” will get into the mix. To Ganis, that’s not a problem; it’s an advantage.

“Thank goodness we consider ‘Drive My Car,’” Ganis said. “Thank goodness we consider ‘Dune.’ That’s another reason why the Oscars are so relevant, because we’re absolutely willing to reach out and find the films that might be obscure but are special and superb in terms of the filmmaking.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.