- Share via

Since he founded the Critics Choice Awards in 1995, Joey Berlin has dreamed of the day when his show might emerge from the shadow of the Golden Globes, taking over as the awards season’s leadoff event and stealing the mantle of “Hollywood’s party of the year.”

That chance appeared to come in May, when NBC pulled the plug on the Globes for 2022 after months of controversy sparked by a Times investigation in February that detailed allegations of financial and ethical lapses among the 87 members of its voting body — and revealed that the association had no Black members.

The absence of the glitzy, star-studded Globes telecast left a void worth tens of millions of dollars in the industry’s awards ecosystem. Berlin — and about 500 broadcast, radio, print and online entertainment reporters and critics from the U.S. and Canada who make up the Critics Choice Assn. — stood ready to fill that vacuum.

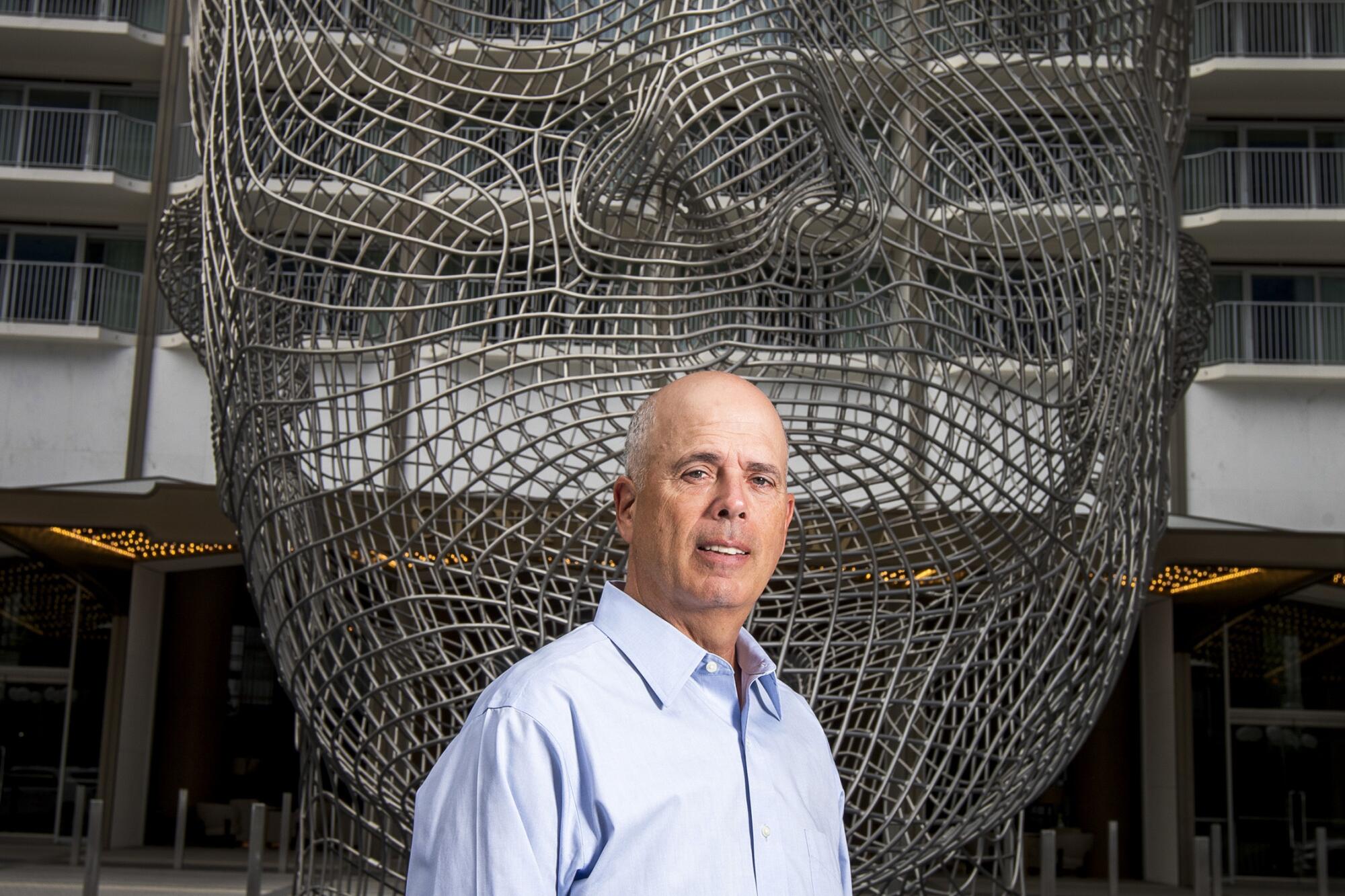

“I’ve been getting all these calls from the industry, saying, ‘We’re counting on you to step up now,’” Berlin, the group’s chief executive, told The Times in late July, as he drank a cup of tea at the Pendry hotel in West Hollywood. “I just feel such a strong wind at our back.”

Even as he tries to capitalize on his rivals’ stumbles, however, Berlin and his organization face their own head winds, both internal and external. The show’s already modest ratings have fallen in recent years as it bounced around TV networks. And, according to some members, the nonprofit organization has been dogged by some of the same issues — including questions over its credibility, governance and potential conflicts of interest — that have plagued the Hollywood Foreign Press Assn., the group that hosts the Golden Globes.

Interviews with nearly 20 current and former Critics Choice Assn. members, as well as a review of tax filings and internal emails, depict a struggling organization largely controlled by Berlin with the help of a close cadre of associates on the board. Berlin has faced scrutiny over his total compensation, which increased 42% to $367,337 in 2019, when the association ran a nearly $800,000 deficit, according to the most recently available tax filing.

Since 2015, at least a dozen members have quit the organization over Berlin’s handling of a number of issues, including how nominations are doled out.

Salt Lake City Weekly film critic Scott Renshaw left the group in 2015, having grown disillusioned with the way the awards appeared to place ratings concerns and industry relationships above artistic considerations.

“It became impossible for me to justify continuing to say they had integrity about the process,” Renshaw said.

One current member who declined to be named out of fear of retaliation said Berlin’s sway over the association has grown unchecked.

“To me there are lots of unanswered questions. The facts aren’t out there. For example, what is our budget, and how much are people getting paid?”

This member said the group’s early years were flush with a spirit of collective optimism, but over time that ebbed. “Once it became a TV event with money behind it, that’s when Joey kept increasing his stake and control.”

With this year’s Critics Choice Awards film nominations set to be announced Monday — the same day the HFPA will reveal its Globes nods — Berlin defended how he runs the Critics Choice Assn.

“This is my life’s work,” Berlin, 67, said. “I’ve built this organization into something that is significant in our industry. I worked really hard, and I’m well compensated and fairly compensated.”

The Critics Choice Awards has long been something of an also-ran. The 2020 show drew just 1.2 million viewers, about half the audience of that year’s Screen Actors Guild Awards and a fraction of the Globes’ 18 million-plus viewers. Viewership for the 26th edition of the show, held in March, plummeted 67%, reaching just 402,000 viewers in a year when ratings for most awards shows were down.

Nonetheless, the Critics Choice Awards, which encompass both film and television, are considered a significant awards-season stop for studios and networks and, as Berlin has frequently touted, a strong bellwether for the Oscars.

The Critics Choice Assn. gives out a large and ever-growing number of awards. The 2021 Critics Choice Awards telecast included 39 categories, 14 more than the Globes; in recent years the group has spun off separate ceremonies to honor reality TV and documentaries, as well as comic-book movies and other genre fare.

With the Globes off the air for a year, Berlin has worked to muscle onto the HFPA’s former turf. He nabbed the Globes’ Jan. 9, 2022, airdate and, soon after, ruffled the HFPA’s feathers by attempting to install the Critics Choice Awards at the Globes’ longtime home, the Beverly Hilton. Eventually, he struck a deal to bring the 2022 ceremony — which will be aired for the first time on two networks, the CW and TBS — to the Fairmont Century Plaza Hotel (it was formerly at the Barker Hangar in Santa Monica). He also established a new international branch, adding a group of foreign journalists to the association.

Berlin has lauded the credibility and inclusiveness of the Critics Choice Assn., whose members mostly hail from regional radio and TV stations and small online entertainment sites and YouTube channels but also include contributors to prominent publications, including the Hollywood Reporter, Variety, Vanity Fair and The Times. Members are divided among television and film branches and vote for their respective categories.

Whereas the HFPA has enacted a series of sweeping reforms to win back the industry’s favor, adding 21 new members, including six who are Black, and overhauling its bylaws, the Critics Choice Assn., Berlin suggested, had nothing to hide.

“We haven’t changed one thing in the wake of any of this,” Berlin said. “We’ve been squeaky-clean all along.”

A Times investigation finds that the nonprofit HFPA regularly issues substantial payments to its members in ways that some experts say could skirt IRS guidelines.

In the mid-1990s, filmmaker Rod Lurie, then a film critic for Los Angeles Magazine and KABC-AM radio, approached his fellow entertainment journalist and poker buddy Berlin with the idea of starting a group for broadcast film critics, believing they were delegitimized compared with their print counterparts.

“I told him we could have a lot of influence and have some fun with it,” Lurie said.

“The fact that he’s been able to pull this off is an unbelievable feat of chutzpah and imagination,” said Lurie, who left the organization in 1999 to focus on directing.

Before founding what was then called the Broadcast Film Critics Assn. in 1995, Berlin, who grew up in Glen Cove, N.Y., on Long Island, wrote movie review blurbs under the byline of Jeff Craig for “Sixty Second Preview,” a show syndicated to about 150 radio stations. Having worked as what some in the industry call a “blurbmeister,” Berlin came to recognize the commercial value in an awards show that would give a critical stamp of approval to Hollywood’s contenders.

“I always talk to the studio reps about how, if we all do our jobs right, everybody wins,” Berlin said. “If you make a good show, we tell our audience about it, and they’re happy, the people who funded your project are happy, we’re happy. It’s a great business to be in.”

Driven by Berlin’s genial boosterism, the Critics Choice Assn. grew from an initial 42 members to about 500. Under Berlin, the group has in recent years inaugurated spinoff awards, including the popcorn-movie-centric Super Awards and an annual Celebration of Black Cinema & Television. Last week, the group held its inaugural Celebration of Latino Cinema, with a virtual show.

“I like to joke, we used to have a show; now we have a franchise,” said John De Simio, a former studio publicist and the group’s executive vice president. “Joey’s vision was to bring this to the broadest possible audience.”

The association derives most of its revenue from awards shows, which generate television licensing, as well as by charging studios and networks to buy tables at the flagship Critics Choice Awards.

The awards ceremony is not nearly as lucrative as the Golden Globes — the Critics Choice Assn. had total assets of $894,993 in 2019, compared with the HFPA’s $62,716,595 in assets ending that fiscal year.

The association has run deficits in six of the last 10 years reported (2010 to 2019), according to tax filings, and has never broken through to a large mainstream audience. Berlin’s effort to reach a wider viewership through this year’s new Super Awards, celebrating comic-book movies and other genre fare, reached just 263,000 viewers.

“The ratings are terrible,” said one current member.

But despite the group’s anemic performance, Berlin has been handsomely remunerated, tax records show.

In 2019, the most recent year for which filings were available, Berlin earned $367,337 in direct total compensation, up from $257,478 the prior year, when he was listed as the group’s president. His wholly owned production company Berlin Entertainment, which helps to produce the Critics Choice Awards, received an additional $655,411 for “production services.” Berlin and Bob Bain serve as executive producers.

That year, the group took in $4,205,834 in revenue but, with expenses, ran a deficit of $784,084, according to a tax filing.

By comparison, that same year, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences CEO Dawn Hudson earned total compensation of $744,789 for running an organization with roughly 10,000 members, more than 450 employees, a museum and revenue of more than $147 million, according to the academy’s tax filing. The academy has been in the black for many years.

Although it’s not uncommon for small nonprofits to pay board members and insiders for services, the question is “whether they are using arm’s length payments,” said Ellen Aprill, the John E. Anderson chair in tax law at Loyola Marymount University. “Are they paying fair market rate, or are they getting a sweetheart deal?”

In a statement, Berlin said the payments to his production company for producing the Critics Choice Awards and its spinoff shows were “wholly appropriate,” adding that he has been the “driving force behind Critics Choice.”

Companies associated with Berlin also have provided other services to the group.

In 2014, the Critics Choice Assn. received board-approved loans totaling $3.05 million from two companies — Berkshire Hills Music and Litchfield Entertainment — tied to Berlin’s wife, Ivy Tombak, according to a tax filing reviewed by The Times. Tombak declined to comment.

Tombak is president and Berlin is secretary of Litchfield, according to state corporate records. Tombak, an attorney, also is listed as the agent of Berkshire Hills, records show.

The Critics Choice Assn. had decided to move the show from the CW to A&E that year and had to pay back the broadcast licensing fee to make the switch, Berlin said.

However, Berlin’s specific association with the companies was not disclosed in the tax filings, nor were details about the loan terms.

“We were really fortunate that my wife’s company was able to loan the organization the money in order to make that deal, which was an extremely important part of the development of the Critics Choice Awards,” Berlin said. “We paid it back a little early. I think there was some interest involved, but it was just a couple of points.”

Berlin declined to provide documentation of the loan terms.

Board member Sam Rubin couldn’t recall a board vote but said he was aware of the loans, and this was “done in an aboveboard and transparent way.”

In its most recent tax filing, the organization said it doesn’t have a written conflict of interest or whistleblower policy, and there is no independent review or approval of compensation for key executives or officers.

That’s unusual for a nonprofit group like the Critics Choice Assn., one expert said.

“For an organization of this size and budget, I would expect to see more formal policies in place to create separation between the organization and the people within it,” said Brian Mittendorf, the Fisher Designated Professor of Accounting at Ohio State University, who reviewed the filings. “Having a system without guardrails opens them to all sorts of problems that can arise when engaging in transactions with insiders or relatives or affiliates of insiders.”

Berlin said he is “confident that the policies and procedures that we have in place are the right ones for a critics group that has grown so successfully over the past quarter-century.”

For many years, the organization’s small board consisted of Berlin, De Simio and three others. This summer, the board added four more directors who were voted on by members. It currently has nine members, according to its website.

But those familiar with the organization say there is little oversight or transparency over decisions, including financial matters.

“Everything is kind of a mystery,” said one longtime member. “One board member I’ve known for a long time, I’d ask him questions, and he’d say, ‘I don’t know. Joey makes all the decisions. I do what he says.’”

Longtime board member De Simio confirmed that Berlin “was always the driving force” behind the group’s key decisions.

Board directors in 2019 received payments ranging from $5,000 to $82,000, according to tax filings. De Simio, who is listed as both a director and executive vice president, earned $122,332.

Rubin, the entertainment anchor for KTLA-TV, was paid $10,000 in 2019 as a director. He and his production company also are compensated for hosting the red carpet show. The group does not break out how much Rubin is paid for his services.

Berlin declined to provide financial details, saying the arrangement was known to the board.

“It is a labor of love for Sam, and if he makes any money for doing it, that compensation is well below market rates,” he said.

According to Rubin, he is paid about $20,000 a year for such services.

“I’m in charge of the broadcast red carpet show and have been for many, many years,” Rubin told The Times. “I was doing it before I was ever on the board.”

Berlin forwarded a statement on behalf of the board, saying it “knows and understands the details of the compensation of all executives of the CCA and all licensing agreements regarding all Critics Choice programs and events, including those reached by Berlin Entertainment, Inc. and Sam Rubin Entertainment, Inc. on its behalf. The Board is confident that no such compensation is excessive or unreasonable, that indeed compensation related to the Critics Choice Awards is ordinary and customary.”

In recent years, several members have left the group in protest over some of Berlin’s decisions.

In 2015, the Critics Choice belatedly added J.J. Abrams’ blockbuster “Star Wars: The Force Awakens” to its slate of best picture nominees after the group had already announced its nominations. Although Berlin said the members were polled on whether to make the addition, the move led to social media derision and resignations from two members.

“The only thing we have is our integrity,” said onetime Kansas City, Mo.-based film critic Eric Melin, who quit the group, along with Renshaw. “Adding the ‘Star Wars’ movie when we had already voted felt like a marketing ploy to get better ratings.”

The following year, more than a dozen members resigned in protest after the organization announced that A&E, which then aired the awards, was partnering with Entertainment Weekly on a multiplatform content and promotional deal for the telecast. The concern was that the arrangement favored the magazine over other media outlets covering the show. Several who quit later rejoined.

“We didn’t find out until a press release went out,” said one of those who quit the group. “It was a communications issue, and it also called into question the integrity of the awards show.”

Board member Shawn Edwards, film critic for Fox 4 in Kansas City, Mo., defended the group. “Sometimes you have to do things to ensure that you get ratings, and that’s not going to make everyone happy,” he said.

Berlin said he regrets the way he handled the episode.

“We thought Entertainment Weekly could be a great partner in helping to grow the Critics Choice Awards, and I did not think it through or ask the proper questions internally,” he said. “I screwed that up.”

The organization said the perception that many members are not serious journalists is “outdated and unfair” and that it is committed to addressing the lack of Black members.

With the awards landscape in flux, Berlin has been trying to highlight the differences between the Critics Choice Assn. and the HFPA to the industry, the media and his own members.

In October, the HFPA announced that, despite being pulled from NBC, it would present next year’s Golden Globes — in a form yet to be determined — on Jan. 9, as originally planned.

In a letter to Critics Choice Assn. members, Berlin blasted the announcement as a “desperate move” by a “scandal-ridden” HFPA to “undercut the Critics Choice Awards and the tremendous support we are receiving from all the major studios, networks and streamers.”

Whereas the HFPA has drawn criticism over issues of transparency about its membership, Rubin noted that the Critics Choice Assn. lists all of its members and their affiliations on its website.

“This is a real body with real members that work for real outlets,” he said.

However, even some within the group question some members’ journalistic and critic credentials. Said one: “Lots of people don’t even do reviews.”

To heighten the contrast with the HFPA, which faced heavy criticism over its lack of Black members, Berlin has touted the results of a recent internal survey the group conducted on its diversity. The survey found that 25% of its members are people of color, with 5% identifying as Black.

“Our numbers are good,” he said. “But we’re also going to try to move and be as perfect as we can, and that’s how we look at it.”

With the industry continuing to hold the HFPA at a distance, increased scrutiny has been brought to the way awards voters are wooed by studios pursuing prizes and the marketing bonanza they can represent.

As with the HFPA, many Critics Choice Assn. members routinely travel to studio-funded junkets, which can include round-trip airfare and rooms in luxury hotels, and are plied with publicity swag as awards races heat up. Members were informed last month in a newsletter that they could accept gifts under $50. The group has long held that its members’ participation in studio-paid junkets is dependent on the policies of their individual outlets.

As trophy-hungry studios and networks navigate this year’s upended awards landscape, Critics Choice Assn. members have continued to be courted as in the past. In recent weeks, members have been invited to studio-funded events for a number of this year’s leading Oscar contenders, including Warner Bros.’ “King Richard,” Focus Features’ “Belfast,” Netflix’s “The Power of the Dog” and United Artist Releasing’s “Cyrano.”

Although junketing is common among much of the entertainment media, Melin said he had left the Critics Choice Assn., in part, over the apparent eagerness of some members to be courted by studios and to “hobnob with famous people.”

“I think they were more interested in predicting the Oscars than honoring the best in film,” Melin said.

Several studios have increased their engagement with the upcoming Critics Choice Awards. Berlin said Netflix, Apple, WarnerMedia and Disney/Hulu are all planning parties around the show.

“It’s exactly what has been done for years with the Globes, where it becomes the party of the year, and the talent just goes from one to the other, and a magical night occurs,” he said.

But looking beyond this year, industry insiders are skeptical that the Critics Choice Awards will be able to displace a brand as established as the Globes.

Even within the Critics Choice Assn.’s leadership, there is a recognition that the Globes are likely to return in 2023.

“It would be nice if we could attain the top spot, but that’s a long and winding road,” De Simio said. “I don’t think it’s a wise bet on anyone’s part to count [the HFPA] out.”

Still, Berlin is undaunted. Looking ahead to the awards landscape five years from now, he said, “I’d like us to be talking about: ‘Whatever happened to the Golden Globes? Do you remember them?’”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.