Can studios compete with streaming services to buy this year’s Sundance hits?

- Share via

This year’s mostly virtual version of the Sundance Film Festival can’t possibly live up to the heady atmosphere that regulars expect. Sundance, and the deal-making that comes with it, thrives on the in-person experience of crowded lobbies and bars along historic Main Street in Park City, Utah, between and after screenings.

But, perhaps counterintuitively, some attendees — tuning in to the film premieres digitally because of the pandemic — still see Sundance 2021 as a major opportunity.

Just ask the executives from Shout! Factory, the Los Angeles-based independent film distributor. Buying a hot title at Sundance for the first time could represent a significant step for the 18-year-old company that made a name for itself selling “Mystery Science Theater 3000” DVDs.

“This is an exciting time for us,” said acquisitions head Jordan Fields, adding, jokingly, that he’ll be getting in the “Sundance spirit” by putting on his winter coat and gloves before watching through his iPad and television. “We’ve bought [films] out of festivals before, but Sundance is new. It’s a measure of where we’ve come from and where we’re going.”

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The fact that any buyers are excited about this year’s Sundance is a minor miracle for an independent movie industry that has had little to celebrate during the COVID-19 crisis.

The festival often sets the tone for the year ahead in indie film, providing a platform for new artists, a launchpad for Oscar hopefuls and an annual pilgrimage for cinephiles. It’s where studios and indie distributors write big checks for what they hope will be the next breakout hit, à la “Brooklyn.”

This year’s edition, which starts Thursday and runs through Feb. 3, has a lot working against it, being largely online, shorter in duration and having fewer film titles for sale. Of the 73 films showing, fewer than 60 are seeking distribution, according to industry sources. That’s down significantly from last year, when about 120 films showed, nearly 100 of which didn’t yet have deals.

Traditional studios that lean heavily on the theatrical business could find it even more difficult to bid against deep-pocketed streaming services this year, given the uncertainty over when movie theaters will reopen.

While only 35% of U.S. theaters are currently open and prolonged closures are expected in art-house-friendly Los Angeles and New York, studios are hoping theaters are more fully open by late summer or early fall. With no guarantees, though, it may be hard for some to justify the seven- and eight-figure offers.

Another problem: Studios normally would be able to use the prospect of a robust theatrical release as a bargaining chip with filmmakers when bidding against Netflix, Amazon Studios, Apple TV+ and HBO Max. Not this year.

Sundance’s Tabitha Jackson won the festival director gig, then the pandemic hit. How she’s leading the film festival’s 2021 edition into the future at a pivotal time in history.

That hasn’t deterred Bleecker Street Chief Executive Andrew Karpen, whose New York-based company is bringing two films to screen at Sundance: Nikole Beckwith’s comedy “Together Together” and the 19th century drama “The World to Come.”

“The number of films available is much smaller than in prior years, but there are people looking for quality content to deliver to audiences,” Karpen said. “Right now it’s hard to promise the allure of a big theatrical release. As a buyer, I’m looking to find films I want to share with audiences, and filmmakers have to trust that they’re going to sell their film to someone who is going to find the best way of connecting with audiences.”

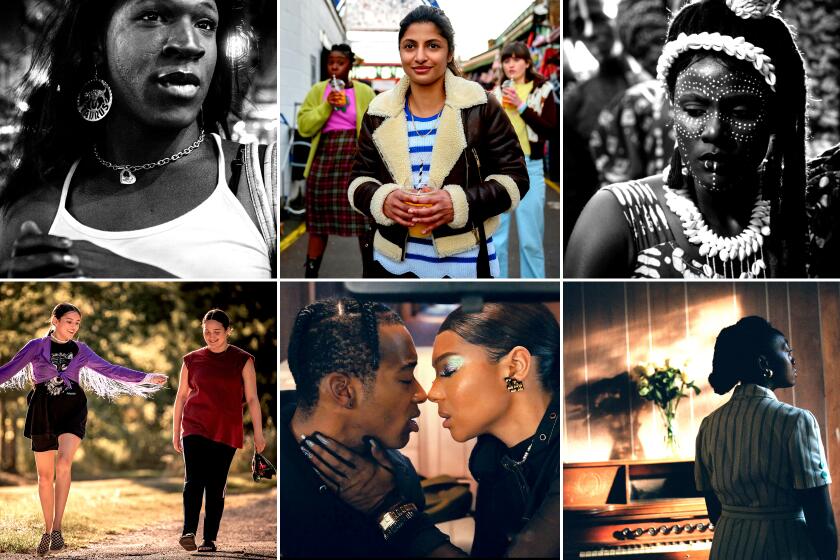

Despite the headwinds, sales agents think studios and streamers will be willing to open their pocketbooks. The lineup features multiple high-profile names behind the camera, including actor-turned-director Rebecca Hall, whose “Passing” stars Tessa Thompson and Ruth Negga in a drama about Black women able to “pass” as white.

Other big titles include “On the Count of Three,” the feature directorial debut from Jerrod Carmichael; Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson’s “Summer of Soul (Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised),” a documentary about the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival; and Sian Heder’s drama “CODA” (short for child of deaf adults).

If theaters do start to reopen by fall, that’s ideal timing for the smaller dramas and comedies that tend attract attention at Sundance.

“We’re all operating under the assumption and faith that our market is going to be opening up,” said Rena Ronson, co-head of United Talent Agency’s Independent Film Group. “Discussing theatrical terms will be part of any negotiation, and it’s going to be on a film-by-film basis.”

Sellers have been heartened by other online events, such as Toronto International Film Festival, where Netflix paid a reported $30 million for “Malcolm & Marie” and nearly $20 million for Halle Berry’s directorial debut, “Bruised.” The upstart Solstice Studios, the company behind last summer’s theatrical release “Unhinged,” reportedly paid $20 million for the Mark Wahlberg drama “Good Joe Bell.”

And while some distributors, such as Sony Pictures Classics and NBCUniversal’s Focus Features, still lean heavily on theatrical releases for their movies, the business has become far less black-and-white. Many indie labels have close ties with streamers, such as A24, which works with Apple TV+, and Searchlight Pictures, owned by Hulu parent Walt Disney Co.

Experts anticipate specialty shingles and streaming services to increasingly “co-acquire” movies. That happened last year when “Parasite” distributor Neon teamed with Hulu to buy the breakout Sundance comedy “Palm Springs,” which turned out to be a fortuitous partnership when theaters closed and the companies pivoted to a primarily online release in July.

The smaller number of films available at Sundance could also become an advantage for sellers.

“Look at the supply and demand side of it,” said Liesl Copland, who runs Endeavor Content’s non-scripted advisory practice. “You have far fewer films coming to the market, and then you have the demand being so high. That creates a dynamic for the commercial films among those new-discovery titles to be sold at a high price.”

We lost theaters, concerts, museums and theme parks. But Hollywood is adapting and so are audiences.

Yet Sundance will be missing the excitement created by the communal experience of long standing ovations, which can influence the studios’ decision-making.

The lack of face-to-face interaction between filmmakers and buyers is also a challenge in an industry where rapport is typically developed over drinks and leisurely meals that can’t be replaced by video conference calls.

Agents such as Endeavor Content’s Copland and fellow executive Deb McIntosh adapted by sending exclusive marketing materials to potential buyers early to lay the groundwork for movies on their slate, including “Passing” and “Users,” Natalia Almada’s documentary about humanity’s fraught relationship with technology.

“You can’t always get your filmmakers, who often have kids and other obligations, on seven different distributor Zooms before the market,” said McIntosh, senior vice president of Endeavor’s film advisory practice. “So taping things like a hosted conversation with the filmmaker or creating behind-the-scenes content to share with buyers ahead of time has proven to be a great alternative.”

Some of the biggest titles already have studios attached. Warner Bros. on Monday will premiere “Judas and the Black Messiah,” Shaka King’s drama starring Daniel Kaluuya as Black Panther Party chairman Fred Hampton and Lakeith Stanfield as FBI informant William O’Neal. AT&T-owned Warner Bros. will release “Judas” Feb. 12 on HBO Max (for a limited time) and in theaters for an Oscar-qualifying run.

Focus Features will launch “Land,” a drama it boarded in 2019 starring and directed by “House of Cards” actor Robin Wright. Last month, Magnolia Pictures acquired the worldwide rights to the science fiction-infused documentary “A Glitch in the Matrix,” screening as part of Sundance’s Midnight section.

The Sundance Institute, founded by 1981 by actor and director Robert Redford, went to great lengths to try to replicate the experience of the festival online.

The nonprofit organization set up an online interactive program, dubbed Film Party, allowing festival passholders to socialize after screenings as if they were playing an immersive video game, in the vein of “Second Life.” The group also organized virtual Q&As, along with in-person satellite screenings in cities around the country, though drive-in screenings in Southern California were canceled as the coronavirus spread.

For digital screenings, attendees will view each film at a set time, each within a three-hour window — another touch to mirror a real festival with so-called appointment viewing. It also opened up the screenings to people who normally wouldn’t make the trip to Park City to buy passes and watch from home.

Still, nothing compares with seeing how an audience reacts in a theater auditorium, one of the intangible factors in studio deal-making, said Sony Pictures Classics Co-President Michael Barker. “There’s no replacement for the information that that experience gives all of us who work in independent films,” he said.

Hype from festival screenings can sometimes lead studios to overpay in bidding wars. Just look at “Hamlet 2,” “The Birth of a Nation,” “Happy, Texas” or any number of Sundance sensations that flopped in theaters over the decades.

If that happens this time, the studio executives won’t even have the thin mountain air to blame.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.