WGA doesn’t just want a deal. It wants Hollywood power reined in

- Share via

Welcome to the Wide Shot, a newsletter about the business of entertainment. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

Hollywood is dysfunctional. The historic writers’ strike, now in its fourth month, leaves little room for debate on that score. But does the entertainment industry behave like a monopoly?

The work stoppages by scribes and actors have renewed focus on the consolidation of the media and entertainment industry in the streaming era, and how those ongoing forces are changing the business for workers and everyone else who makes movies and television shows.

Amid the restart of contract negotiations between the Writers Guild of America and the major studios after more than 100 days of picketing, the screenwriters union’s West Coast branch released a 15-page report critiquing the trend toward having production and distribution under the same corporate roof, a strategy known as vertical integration.

The document, titled “The New Gatekeepers: How Disney, Amazon, and Netflix Will Take Over Media,” argues that those three firms in particular have positioned themselves to concentrate power over those who supply content, including not just writers but also independent production companies and others.

It’s a point that has gained some broader purchase.

Lina Khan, head of the Federal Trade Commission, told the Ankler on a recent podcast episode that “increasingly, we see some of the red flags that suggest the market structure is not actually serving the creators or the ultimate viewers.”

A recent Los Angeles Times op-ed by entertainment industry attorney Miles Mogulescu suggested the time has come to break up the streaming giants, drawing a parallel between the current moment and the film business of the early 20th century, when studios controlled movie production and theatrical exhibition. The Supreme Court forced the divestiture of the studios’ theater assets in 1948, resulting in settlements known as the Paramount Decrees.

The WGA’s paper doesn’t go as far as to demand the breakup of Netflix and its peers. It does, however, cite the long-dead Financial Interest and Syndication Rules (widely dubbed Fin-Syn) — which the Federal Communications Commission imposed in 1970 to prevent the big three broadcast networks from wielding excessive power — as an example of past government intervention.

“The government has historically been concerned with attempts to monopolize media and entertainment,” said Laura Blum-Smith, WGA West’s research and public policy director. “In times when there have been those efforts — and they are perennial — the government has taken action. We’ve seen that the current situation demands that kind of action.”

The Wide Shot spoke to Blum-Smith to drill down on the finer points of the guild’s report.

This report provides a good summary of how we got to where we are today and explains why the WGA is seeking better pay and conditions for its members to counteract the effects of consolidation. With the WGA and the studios back at the table, why release this now?

The guild has been engaged on this topic for decades. We’ve been calling attention to the way that mergers have consolidated power among employers, and how they are harming writers and the diversity of content in the industry.

There has been a recent interesting change in the landscape, which is really about how antitrust enforcers and regulators are questioning the way that antitrust law has been interpreted and enforced for the last few decades — questioning ideas like the consumer welfare standard and giving a lot more attention to the ways that anti-competitive actions and mergers harm workers.

Attempts to monopolize markets are a key part of the history of media. They’re also a key part of what led to the current strike.

The consumer welfare standard, to clarify, refers to the doctrine by which antitrust regulation has traditionally worked in this country — analyzing whether a merger hurts customers by raising prices, for example.

The consumer welfare standard was this narrow focus of antitrust enforcement that was really geared toward considering consumer price increases as the metric for how to define illegal mergers or behaviors. The courts and enforcers adopted that standard over many decades. Many, many mergers have been approved on the basis that they will bring “efficiencies” that help lower companies’ costs and will, speculatively, lower costs for consumers. There’s a broad recognition now that this standard has failed to protect competition.

The report calls out Disney, Amazon and Netflix, specifically as wielding anti-competitive power. But conventional wisdom would suggest there’s still quite a lot of competition in the streaming marketplace. There are still so many streaming services, and none of them have achieved dominant market share.

These three companies are the ones that seem, based on their actions, most invested in dominating the streaming market. And streaming is very clearly becoming the primary market for content. These three are the truly global streaming services, and that gives them immense power to cut everyone out of participating in the growth of the business.

These companies have the power to say there is no more backend for anyone, there’s no participation, there’s no growth in residuals as viewership or revenue grows. That’s massive power over workers and suppliers. I think the narrative that there’s too much content and there are so many streaming services doesn’t reflect how uncompetitive the market is. The way the market is currently structured, with this very high level of vertical integration, makes it extremely likely that there will be more consolidation.

Does it give you hope that some studios — including Warner Bros. Discovery — are now saying that the strict “walled garden” strategy doesn’t work for them, and that they have to go back to licensing material to third parties to remain sustainable? (HBO’s “Insecure” now streams on Netflix.)

It seems like what they’re really talking about it selling off library content. From what they’ve said thus far, it doesn’t appear to me to be a wholesale shift in the fundamental strategy when it comes to their high-profile content.

You describe Disney as having built up market power through its acquisitions of Pixar, Marvel, Lucasfilm, Fox and others over the years. On the flip side, the company is now considering spinning off linear networks including ABC and finding a minority partner for ESPN. There’s even some speculation that they might someday sell to Apple, which Disney has pooh-poohed. Does that worry you?

Apple is certainly another company with massive market power in related businesses. There’s a question of whether they’re actually trying to leverage that to dominate media, and we’ll see. But Apple buying Disney is absolutely an example of what we’re talking about in terms of the kinds of harmful mergers that regulators and enforcers should be prepared for, because there’s this never-ending demand from Wall Street for more consolidation. That would need to be treated extremely skeptically.

Netflix, on the other hand, really hasn’t done that much acquiring. They haven’t bought a competing streamer; they haven’t bought a real studio, the way Amazon bought MGM. They’ve mostly built it up themselves. How do you deal with that from an antitrust perspective?

What Netflix has done is make some smaller acquisitions that show its intent to increase its dominance and market power. Acquiring IP. Acquiring businesses in related sectors. These are part of the market domination playbook.

We’ve seen some of the limits of antitrust action. Some attempts by regulators to block high-profile deals have failed. The government stopped Simon & Schuster from merging with Penguin Random House. Instead, Simon & Schuster is being sold to private equity firm KKR, which worries some observers. How should the government strengthen antitrust?

There isn’t just one answer. We’re calling attention to how harmful it is for competition and for consumers and for writers to have a very small number of vertically integrated companies controlling media. And what we’re noting is that the current market structure makes a three- or four-firm oligopoly very likely, unless there’s some kind of intervention. There needs to be investigation and enforcement in order to prevent that.

So that means blocking the next terrible merger. It also means looking at how to address the current market structure. Separation of production from distribution. Rules against self-preferencing. We just think all available tools need to be looked at. The government has historically paid attention to this threat and taken these kinds of actions.

Stuff we wrote

— Lizzo’s brand was built on empowerment and acceptance. Her accusers tell another story. The musician is facing a lawsuit from ex-backup dancers that threatens to undo her hard-won image.

— Three takeaways on the state of the global games market (Hint: it’s growing). The games business will generate $187.7 billion in 2023, up nearly 3% from last year, a new report from Newzoo projects.

— Trump expected to skip Fox News debate. Moderators say they’re ready. The former president may instead do an interview with Tucker Carlson to counterprogram Fox’s event set for Wednesday in Milwaukee, according to reports.

— DeSantis says he’s ‘moved on’ from Disney district fight as the company doubles down. Disney filed counterclaims in its legal dispute in Florida, seeking damages after DeSantis allies sought to strip its special privileges covering Walt Disney World.

— ‘Avatar: The Way of Water’ financier accuses Disney of self-dealing in new lawsuit. A new TSG Entertainment lawsuit accuses Disney of undercutting its share of movie profits, a move reminiscent of Scarlett Johansson’s 2021 case.

— The WGA and AMPTP are talking again. Why the studios were motivated to return to the table. The two sides were talking all last week after months of impasse as studios reckoned with how badly the strikes are threatening their business.

More strike coverage:

- Pizzas and protests: How Hollywood picket lines differ

- Idled by the strike, screenwriters and actors compete on the softball field

- A-list actors may be on strike, but you can still watch them work. Here’s how

Number of the week

Warner Bros.’ latest DC film “Blue Beetle” opened with a soft $25 million in the U.S. and Canada. It’s hard to say how much we should blame the SAG-AFTRA strike’s hampering of star-driven marketing, versus the relative obscurity of the comic book character compared with the bigger names.

Separately, the $8.3-million debut of Universal’s talking-dog comedy “Strays” does not inspire much confidence in current theatrical demand for bawdy, foulmouthed humor, especially after the struggles of “Joy Ride” and others. Comedy can still work (“Barbie”). Studios just need to find other ways to make people laugh.

Best of the web

— Free ad-supported TV streaming services are booming. One in three U.S. viewers tune in. (TechCrunch)

— “Long-Term Damage”? Bob Iger, Ted Sarandos, and David Zaslav’s bad-PR summer. (Vanity Fair)

— Why is the former ArcLight’s Cinerama Dome still dormant? (New York Times)

— Stephen King, Zadie Smith, and Michael Pollan are among thousands of writers whose pirated works are being used to train AI. (The Atlantic)

— Related: “I would rather see my books get pirated than this.” (author Jane Friedman)

— James Andrew Miller discusses ESPN’s big gamble on the Press Box pod. (The Ringer)

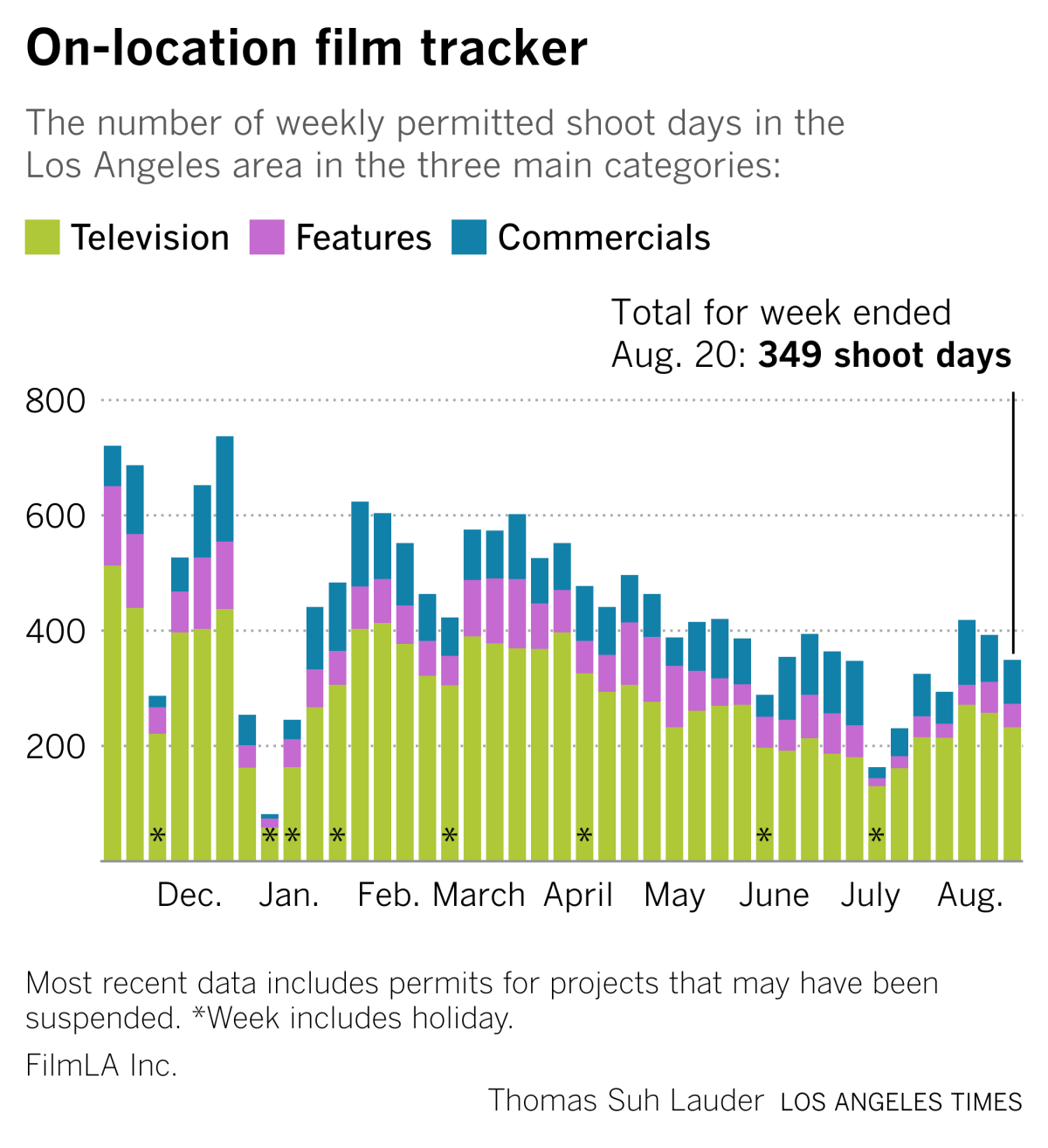

Film shoots

FilmLA shooting permit data continues to paint a bleak picture for the local economy.

Finally ...

Park Chan-wook’s “Oldboy” turned 20 years old this year. What better excuse to revisit the “Vengeance” trilogy?

The Wide Shot is going to Sundance!

We’re sending daily dispatches from Park City throughout the festival’s first weekend. Sign up here for all things Sundance, plus a regular diet of news, analysis and insights on the business of Hollywood, from streaming wars to production.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.