‘Rust’ turned deadly. The business model also deserves scrutiny

- Share via

This is the Nov. 2, 2021, edition of the Wide Shot, a weekly newsletter about everything happening in the business of entertainment. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

First of all, if you haven’t yet read my colleagues’ story reconstructing the day Alec Baldwin fatally shot cinematographer Halyna Hutchins and wounded director Joel Souza, please do so.

Based on Santa Fe County documents, interviews, internal communications and other sources, The Times’ piece published Sunday is the most comprehensive account to date of what led up to the deadly incident on the New Mexico set of “Rust.”

The story — by Meg James, Amy Kaufman and Julia Wick — paints a portrait of a set troubled by bad decisions and budgetary pressures that contributed to tensions between crew and producers. “It always felt like the budget was more important than crew members,” Lane Luper, the A-camera first assistant, told The Times.

Rust Movie Productions has said the company was “not made aware of any official complaints concerning weapon or prop safety on set.” Baldwin, while addressing photographers on the side of a Vermont road over the weekend, described the “Rust” team as “a very, very well-oiled crew shooting a film together” before “this horrible event happened.”

The law enforcement investigation continues, and no charges have been filed. It’s still not clear how real bullets instead of blanks ended up on set, as Santa Fe Sheriff Adan Mendoza last week indicated they had.

The incident also has drawn increased scrutiny of the pressure-cooker economics of low-budget filmmaking in the streaming era, as Josh Rottenberg recently wrote. The gold rush for content has attracted new producers and financiers into the business of indie production. They hope to fund and produce movies that can be filmed with big-name actors — quickly and for little cost — and sold to a streaming service for a healthy profit.

Low-budget filmmaking has been part of the Hollywood story for decades. Dozens of small, independent movies get made every year, and deaths remain rare. Necessity being the mother of invention, some of the best ideas in filmmaking come when budgets are limited. John Carpenter made the first “Halloween” in 20 days with $300,000 and a modified Captain Kirk mask.

In the classic, romantic version many people think of when they imagine indie filmmaking, a low-budget production is a team of scrappy young strivers making a movie with nothing but a flimsy notion that the finished product might actually be seen by audiences.

But the business of churning out indie films for streaming services is somewhat akin to the house-flipping market. Some flips are well done and professional, where the investors clearly spent the necessary money and time and hired the right people to get the job done. Other flips look fine from the outside, but when you take the tour, you notice the floor buckling under your feet.

As the fallout from the “Rust” tragedy continues, members of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, or IATSE, the union that represents crew, are preparing to vote on whether to ratify a new contract agreement that labor representatives reached with studios. Many of the issues that IATSE members have sought to resolve for years, including long hours and a lack of rest time, have been exacerbated by the insatiable demand for content on streaming services.

We’ve talked so much in this newsletter about the ways the streaming revolution has changed Hollywood for the big names and executives. It’s worth also considering how those changes have made life harder, and sometimes more dangerous, for so-called below-the-line workers.

Further reading about on-set safety: What you should know, and what you can do

Hollywood production

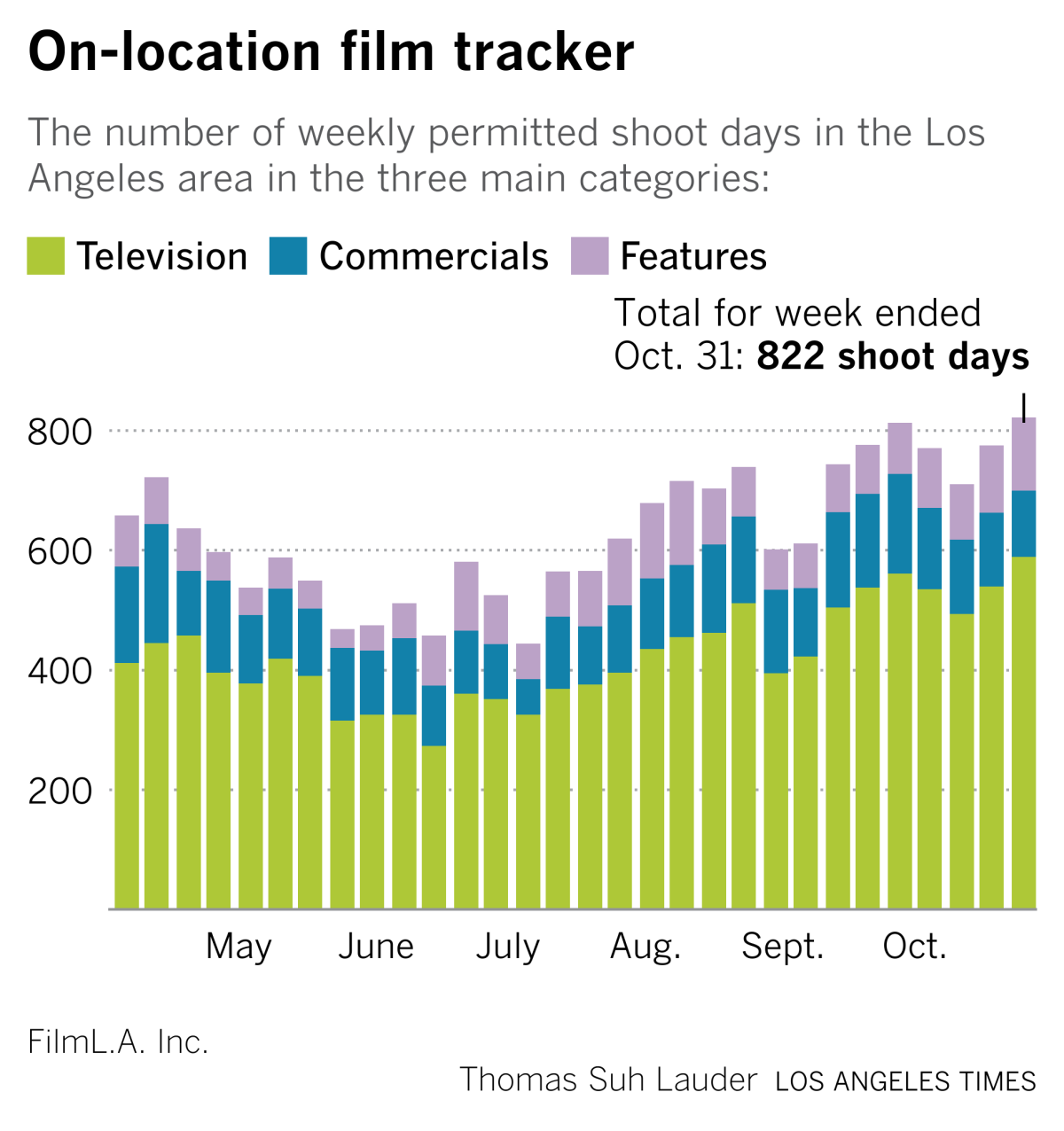

Production days in the Los Angeles area for the three main categories (film, TV and commercial) last week hit their highest levels since the COVID-19 pandemic began, according to data from FilmLA.

The Globes are back?

The Golden Globes are trying to stage a comeback. But not all of Hollywood is buying it. Stacy Perman and Glenn Whipp write that plans by the Hollywood Foreign Press Assn. to give out nominations and awards for next year’s 79th Golden Globes hit the industry “like a thunderclap.”

Within days of the HFPA’s the-show-will-go-on announcement, a 100-strong contingent representing content makers, talent and entertainment executives met over multiple Zoom meetings in an attempt to figure out how they would respond.

After all, NBC has said it won’t televise the 2022 Golden Globes and a group of powerful publicists continue to boycott the group. A slate of studios, networks and streamers cut ties with the HFPA following a Los Angeles Times investigation in February that brought to light allegations of financial and ethical lapses and pointed out that none of the association’s then 87 members was Black.

According to three individuals who participated in the discussions, the HFPA’s move caught everybody by surprise. When the discussions ended, the majority concluded that they would decline to submit their films, TV shows or talent for award consideration.

Number of the week

Peacock decided not to strut its stuff in Comcast’s most recent earnings report, at least not as much as it has in the past.

Jeff Shell, chief executive of Comcast’s media and entertainment arm NBCUniversal, said the service “added a few million more” monthly active accounts. But the company declined to give specifics on signups, unlike in previous quarters.

The last time Comcast disclosed Peacock user numbers was in July, when it said it hit 54 million signups, including more than 20 million monthly active users. Importantly, that data accounted for the first few days of the Tokyo Olympics, which was a big boost for the service. Comcast has never disclosed how many people actually pay for Peacock.

Unlike some of its peers (Disney and WarnerMedia), Comcast has not gone all-in on streaming. It also has an unusual business model, with a mix of free users and paid subscribers, which makes comparisons weird. For what it’s worth, ViacomCBS doesn’t break out specifics for Paramount+ either, instead choosing to release combined subscriber counts for all its streaming services, including Showtime’s direct-to-consumers offering.

Although Peacock is growing, it’s losing money. The service lost $520 million on $230 million in revenue in the third quarter, compared to a loss of $233 million last year, Comcast reported. Streaming services typically post losses when they’re starting out.

Peacock needs more original hits to compete, analysts say. MoffettNathanson, in a recent research report, called the service, “by any reasonable standard, a disappointment” and argued that the company “will have to spend more.”

But Shell made the case for Peacock by saying that, in just a year of existence, the service is “already more than 1/3 of where Hulu is now,” which has been around for more than a decade. (Comcast is a Hulu shareholder.) He said Peacock was ramping up its original programming after getting off to a slow start during the pandemic.

“We’re really pleased with Peacock,” Shell said. “It’s way ahead of where we expected to be at this point.”

Also:

The movie business’ return to releasing theatrical films is affecting earnings in interesting ways.

Universal Pictures’ revenue increased 27% year over year thanks to the theatrical release of movies including “F9” and “The Boss Baby: Family Business.” However, studio profit dropped 47% to $179 million, partly because the company went back to pre-pandemic levels of spending on production and marketing.

Other studios will probably report similar results as the recovery continues. Sony Pictures, which made a lot of money earlier during the pandemic by selling movies to streaming services, reported a 35% revenue jump in its most recent quarter, while operating income shrank 7%.

Stories from the week

— A nation learns to love movie popcorn — without the movie. South Korea’s COVID-19 restrictions banned eating popcorn in theaters, so people chowed down in the lobby or had tubs delivered to their homes. (Wall Street Journal)

— Movie history has never been more accessible, so why do classic-film fans still feel it’s threatened? (Indiewire)

— “Met averse?” Charlie Warzel analyzes Facebook’s name change. “There’s not much new to say because little actually happened.” (Galaxy Brain)

— “Star Trek” is the greatest sci-fi franchise of all. Why it’s stood the test of time (LAT)

— How Ryan Reynolds built a business empire. The actor and entrepreneur has turned his on-camera charisma into major marketing savvy. (WSJ)

Finally...

If you find yourself back in crosstown traffic on your way to a lunch meeting when you’re on deadline (not that I would know anything about that), a good de-stresser might be the War on Drugs’ new album, “I Don’t Live Here Anymore,” which features an incredible title track. I’m also eager to discuss Edgar Wright’s “Last Night in Soho,” so hit me up.

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.