He wasn’t a crier, but then his wife died — and the tears wouldn’t stop. How one father found his way forward

- Share via

Warren Kozak used to wonder whether he had a personality defect because he rarely if ever cried.

Kozak was very close to his grandmother, and when she died suddenly, he felt terrible but didn’t cry. When his parents died years later, the same experience — very sad, but no tears.

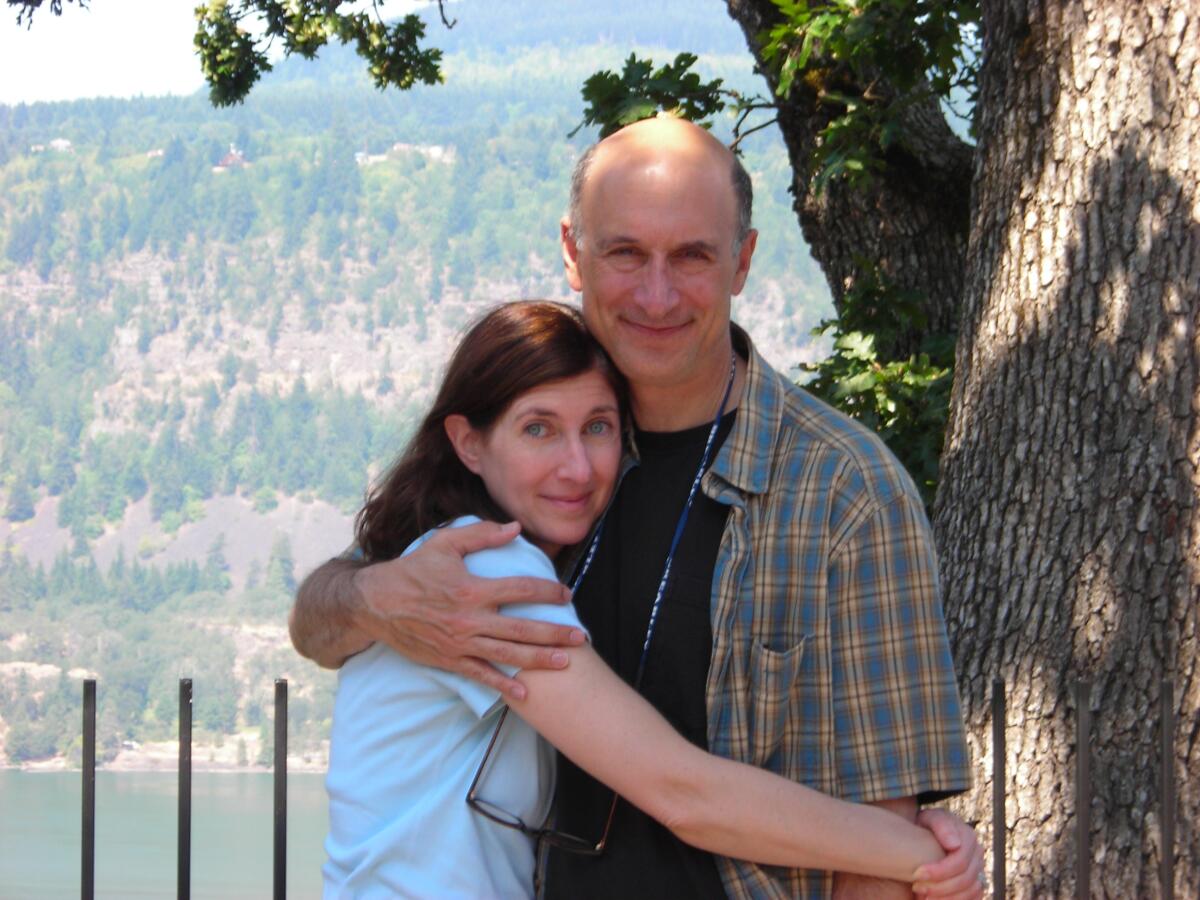

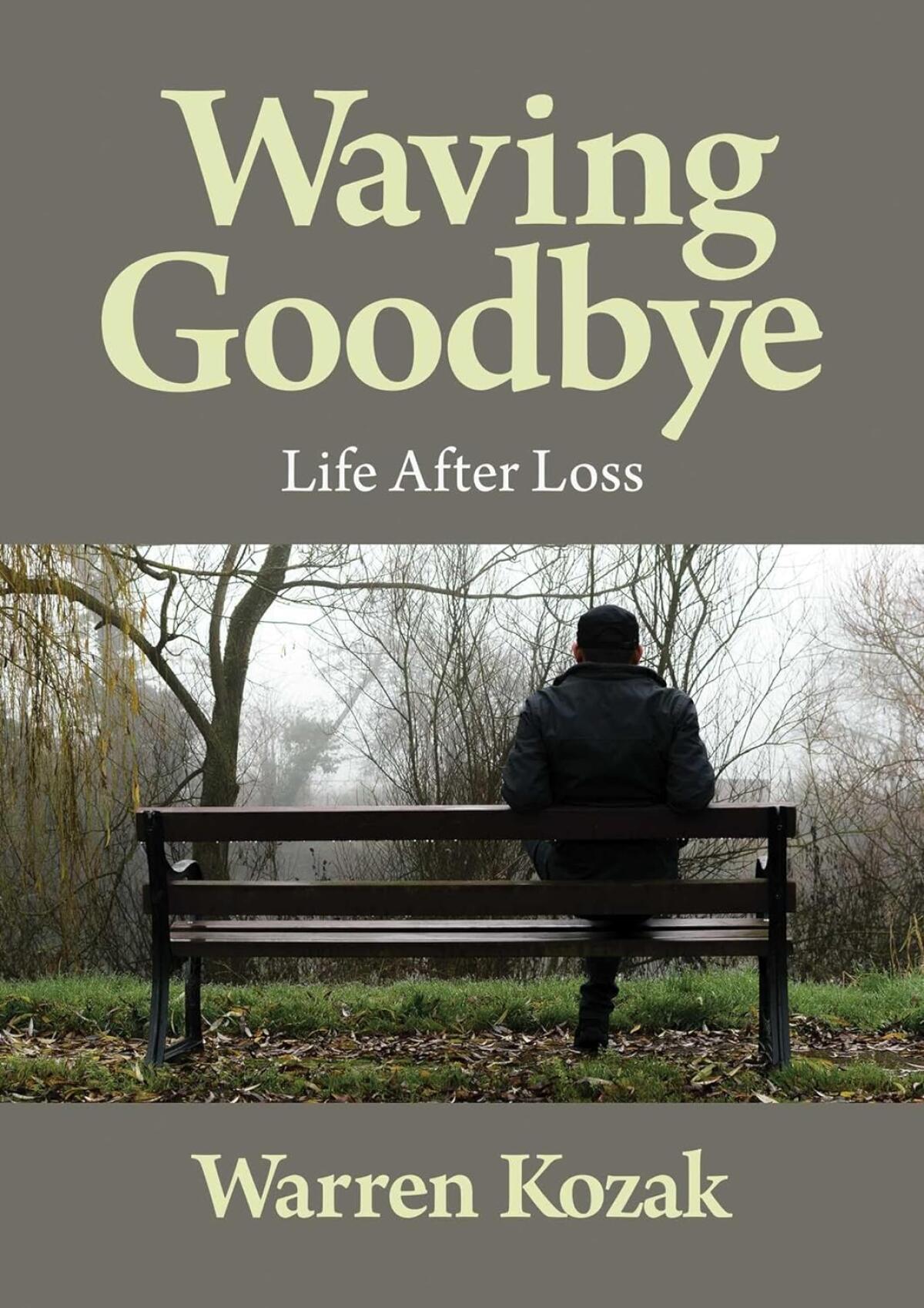

In Kozak’s book out this month, “Waving Goodbye: Life After Loss,” he says the death six years ago of his wife, Dr. Lisa Krenzel, finally opened the floodgates. After Krenzel died, especially during the first year, Kozak says, he “made up for all previous years everywhere and all the time.”

Kozak would lose control of his emotions in very uncomfortable places — on the subway, where it became necessary to wear sunglasses; walking down the streets of New York; on the elliptical at the gym; and at work events where he would excuse himself, go to the bathroom and shut the door to the stall.

That first summer after Krenzel’s death, Kozak was doing the crawl in the waters near his family’s Wisconsin lake house when he “just burst into tears. Never a great idea,” he writes, “when your head is underwater.”

In the end, though, Kozak realized that he didn’t just write a book on bereavement. He wrote a love story as well. “After six years without her, I am so grateful for these memories,” he writes. “I never expected to write these words at the end of this story, that I consider myself lucky, but I do now.”

The Times spoke with Kozak about his book. The conversation has been edited lightly for length.

The awful moment came on Jan. 1, 2018, when you saw Lisa take her last breath. For the last two years of her life, you anticipated Lisa would die at some point. But you didn’t expect to react as you did when the end finally came.

It really surprised me. Look, you don’t know how you’re going to act at that moment. I kind of imagined that I would be calm and even heroic. I was as far from heroic as you could imagine. My brain just completely canceled in a way that I had never experienced. I suddenly had trouble breathing.

Different religions have different traditions at this moment. Catholics cross themselves. I’m Jewish, and one is supposed to recite a very short Hebrew prayer. It’s one sentence. I even had the prayer book sitting there in anticipation. But when I opened it up — and this had never happened to me before — I could not read it. The words I saw on the page would not come out of my mouth. I really mangled it. I just closed the book and gave up completely. Then you have to settle yourself down because there are things you have to do. So being able to concentrate on those things finally got me moving. It took a long, long time before my brain was normal again.

Your daughter Claire happened to be home from college when Lisa died at 4:30 a.m. I can’t think of anything harder than waking up your daughter to inform her.

Claire was right in the next room. Our bedrooms share a wall. I had to go in and tell her. Yes, it’s one of those moments I don’t like to think about. But I told her I’d stay with her, and you know what? There’s no way you can make it easy for someone losing a parent, especially at age 19.

Then you brought her into your bedroom. That must have been hard.

It was beyond hard. If I had thought about it, this was the first time Claire had ever seen someone dead. And it was her mother. So it was a huge shock for her, in that regard, too. I think we all remember when we see someone for the first time who has died. I could do nothing to protect my child from the greatest hurt of her life.

How’s your crying these days?

A lot less, a lot less. The way I describe it: The first year, I had no control over it. It was a lot better the second year and better still the third year. It still happens but very rarely. It’s now more like a sneeze. I can feel it coming on. And the duration is just about as long as a sneeze. It is often from two things: from someone’s kindness, which I still can’t figure out; and then there’s certain music that’ll trigger a switch in my head and that’ll bring on that sneeze cry.

When you returned from burying Lisa in Wisconsin, you had a week-long shiva, the Jewish ritual of friends, family and neighbors visiting after the death of a loved one. How did shiva help you?

It was a life saver, frankly, and I never understood the value of it until this happened. It should be pointed out that every single religion, every culture has some form of this. Catholics have wakes. And it’s necessary. I think human beings figured out over the millennium that this is what is needed.

I was forced to be social at a moment when all you want to do is just go into your room, close the door, not see anyone, curl up and put a blanket over your head. People are coming into the house constantly and you have to say hello. You have to thank them for coming. You have to pretend you’re normal. And what I described in the book was I felt like I was acting. I was playing the role of “normal me” and I wasn’t “normal me.”

But in retrospect, this forced me to act normal, and it kind of brings you back into life again. You’re just in a totally different realm. The shiva also reinforced something for me that I needed at that point: I needed to remember that I had friends and, of course, there were people that cared about Lisa. But for some reason, I needed that validated, and the shiva validated it.

Six years out, how close are you to the ‘normal me’?

I think I’m almost there in a lot of ways, but I am forever changed. I am not the same person. And that came across in an email a friend sent me. You’re not the same person after something like this. But whoever that new person is, I’m a lot closer to it. I have much more control over my emotions. My concentration is better. The first year I had zero concentration. So the brain comes back, but I’d say I’m different. I’m not the same person.

Why did you write this book? It had to have dredged up memories that you’d rather forget.

First of all, this is a book I never planned on writing. Something triggered it. About five years after Lisa died, I found an email from a friend — very thoughtful and provocative. It left an impression on me that I put the entire email into my diary. It was that email, and a follow-up conversation, that just made me sit down and start writing, and this book poured right out of me in just several weeks. Then I edited it for a long time.

Caleb Carr discusses grief and dying — subjects that linger over his new nonfiction book, “My Beloved Monster,” and now loom over what might be the final months of his life.

Right after Lisa died, people brought books to help me. But nothing that was given to me helped. That doesn’t mean these books don’t help other people. They just didn’t help me because many of them were written in a very academic style by psychologists and doctors and grief counselors and clergy. One of the reasons was my fault — my brain was just not functioning the way it did right before Lisa died. And I think the trauma, the shock of her death, caused this brain dysfunction.

You mention how five pages of Joan Didion’s book “The Year of Magical Thinking” were superb — pages that you copied, reread again and again, and have emailed to others who lost a partner. What did she offer that others didn’t?

There’s a line in the Didion book that really resonated with me. A friend of Didion’s told her, “After a year I could read headlines.” I could so relate to that because basically, I could just read headlines. I didn’t have the concentration to read entire articles, which was a problem because part of my work is having to read long, more complicated and intricate pieces of writing.

But some of the books I got were pure academic drivel, totally useless, that gave me no guidance or comfort.

Steve Roberts wrote a book about losing his wife, journalist Cokie Roberts. His son noted that the father of a good friend had died and the mother put the house on the market six weeks later. Roberts said, “That’s not me.” You seem to be following Steve’s advice.

I have wonderful memories of the apartment we shared. My God, I remember bringing Lisa here for the first time. And we came here right after our wedding before we went off on our honeymoon. We came here when we brought our daughter Claire home from the hospital. I have such wonderful memories of this place. So the idea of selling the apartment has never crossed my mind. I still get such happiness coming through the front door. And I never thought I would say that. You know, I talk about coming through the front door for that first time by myself after the shiva and how awful it was — a silence, the likes of which I never experienced before. But now I can come back in and I love being here.

In advance of this year’s Los Angeles Times Festival of Books, we’re unveiling our Ultimate Hollywood Bookshelf. Find out which novels, memoirs and more made our list.

How have you celebrated Lisa’s life in the six years she’s been gone?

I’m not sure this was a celebration, but I needed her to be remembered. It became so important. I was writing a Wall Street Journal op-ed on the paperwork of death — the mistakes I made and others can learn from. They asked me to send a photo. The day the op-ed ran, I took a screenshot of the front page of the Wall Street Journal that day because they had a picture of three op-eds and her picture was on the front page. I was so afraid of her being forgotten.

Look, I realize that eventually, we are all forgotten. You know, just another generation or two. People didn’t know us. The world moves on, and that is just the way it is. It’s the way it’s always been. But right now, I needed her to be remembered.

You asked the maintenance workers at Lisa’s graveyard to call you as they were preparing to install the new gravestone, so you could be there. What happened next surprised even you.

It still surprises me. I still can’t believe this happened, and it’s a little shocking. I had to put in a great big new headstone. They dug up the grave to put a base of cement for the headstone to sit on; otherwise, it would just eventually sink from its weight.

I was looking down at the casket and I just suddenly lowered myself into it. I rested my hand on top of the coffin. The maintenance guys were very sweet about it. They saw what was happening. They turned and walked away to give me some privacy. This gave me a great deal of comfort and happiness to be that close to her again. I imagined Lisa lifting her hand on the inside and reaching out to touch mine. What an unexpected gift.

A few touches of humor are sprinkled throughout your book. I laughed at your comments about what Lisa’s first question would be when your time comes and you’re lowered next to her.

We held the short burial service for Lisa in a howling wind and minus-5-degree temperature. Lisa absolutely hated the cold, and standing there, with each strong gust of wind, I thought that when my time comes and I am lowered right next to her, her first question will be: “What the hell were you thinking? It is so damned cold here.”

Terminal Island may be best known for the Japanese American village tragically uprooted by government order. A new book mines its history as that — but also as resort, artists colony and more.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.