How journalist Michele Norris exposed our ‘Hidden Conversations’ about race

- Share via

On the Shelf

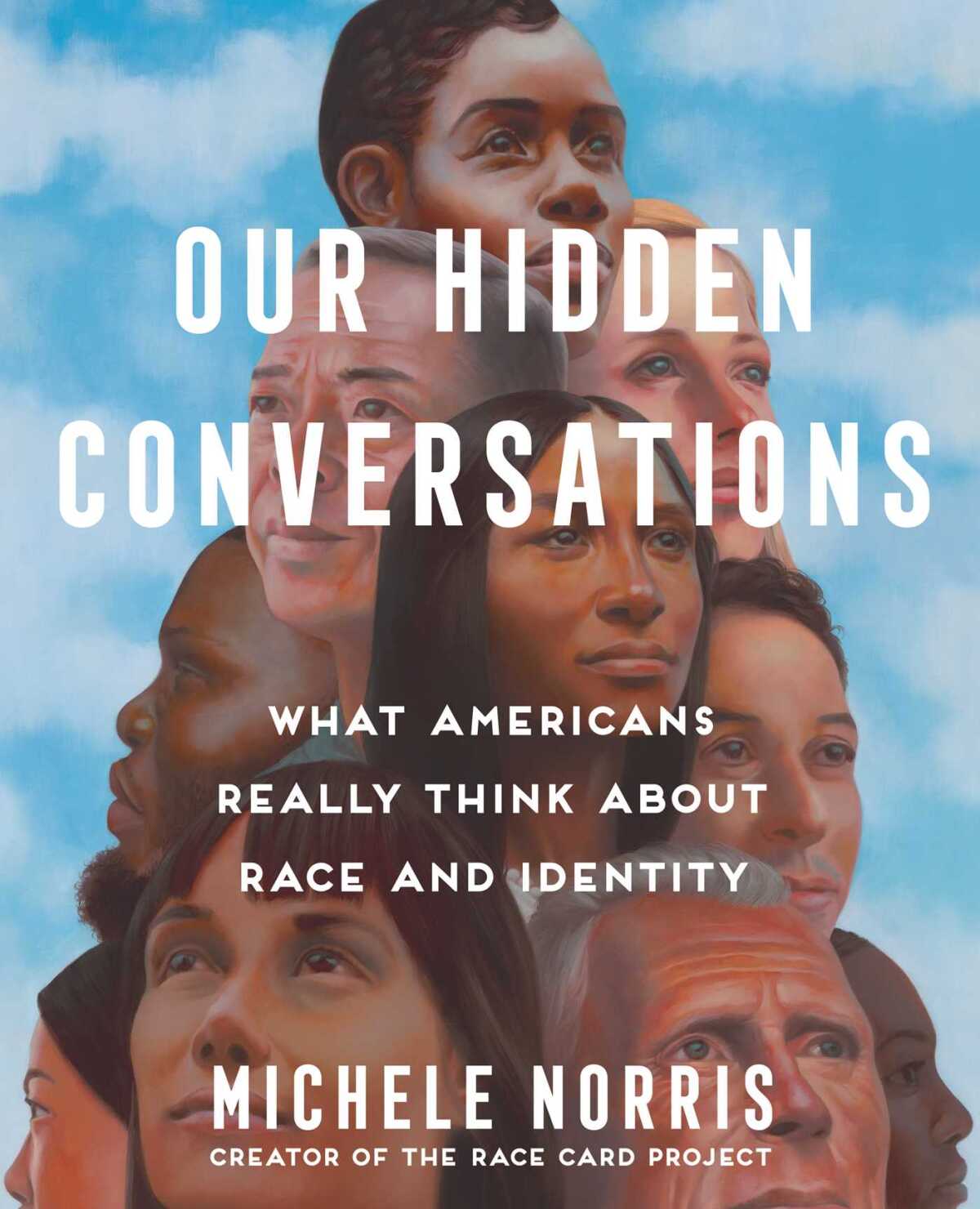

Our Hidden Conversations: What Americans Really Think About Race and Identity

By Michele Norris

Simon & Schuster: 528 pages, $35

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Michele Norris remembers inadvertently eavesdropping on her grandparents’ neighbors during the hot summer days when she would visit Alabama. There was no air conditioning, so people had to throw their windows open and risk all of their dinnertime conversations being overheard.

But ever since 2010, when Norris, a Peabody Award-winning journalist for many publications (including The Times) and former co-host of NPR’s “All Things Considered,” launched the Race Card Project, asking people to submit six-word sentences about race, she has — “with permission” — been eavesdropping on a sizable sampling of the nation. Now it’s all collected in a new book, “Our Hidden Conversations: What Americans Really Think About Race and Identity.”

“That’s what this book feels like,” Norris said during a recent phone interview. “The windows are open and I get to hear America.”

The book features essays written by Norris alongside submissions from people around the world about their intimate thoughts on the intersections of race including their children, their marriages, their commutes, their jobs and interactions at gas stations and grocery stores. The format is inspired by such works as Studs Terkel’s “Working” and “Hard Times,” as well as Toni Morrison‘s cultural anthology “The Black Book.”

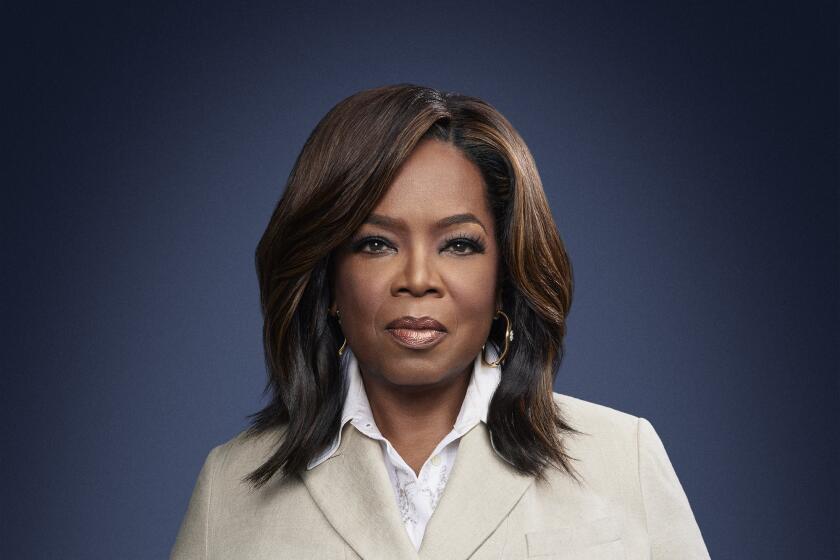

Ahead of a new documentary about racial inequities in healthcare, the TV host opens up to The Times about her own experiences.

It comes at a time when “we are still struggling with reckoning with race in America,” Norris said — and seeking answers as Americans debate the teaching of history and critical race theory. It’s difficult, she added, to tell the story of America unless people are willing to examine and embrace how race intersects with topics such as politics, sports, health, housing and education.

The book also surprised her. “I created the Race Card project because I thought that nobody wanted to talk about race,” Norris said. “It’s true that people are uncomfortable talking about race — that has been my experience as a human being and as a journalist. But this project, if anything, has shown me that a lot of people actually do want to talk about it, that in fact they talk about it all the time.”

She also hopes that the book becomes an indispensable historical artifact: “Imagine what this will mean to someone years from now, that is trying to understand the sort of messiness that we’re experiencing,” she said. “... Maybe it will be in service to people, to journalists, to sociologists, to researchers, to storytellers of the future, who want to understand this time that we’re living in right now.”

Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

When did you realize you wanted to make this book?

I realized pretty quickly that I needed to collect these in a bigger way. At the very beginning, when the cards started coming in, I knew — “OK, wait a minute, people, we’ve cracked the code here.” People are really opening up, they’re sharing things that I don’t hear in studio. I was a host of “All Things Considered” at the time, I’m hearing things that I don’t hear when I’m out in the world reporting.

Which essay in the book challenged you the most?

There are a couple that challenged me. “Black babies cost less to adopt” challenged me and challenges me even now. When I go back and read what I wrote it hurts. It makes me angry. It makes me very sad that we established this sort of caste system from birth. And that in something as beautiful as adoption, when people open up their hearts and their homes, that there are market forces at work. I have not enjoyed that work. There’s joy in the work of writing, there’s joy in the collection of stories, there’s joy in the reporting, even when it’s difficult, [but] that really taxed me. That has tap danced on every single one of my emotions in reporting that story and meeting various people involved in the process.

Kerry Washington discusses her memoir, ‘Thicker Than Water,’ and the family secret revelation that taught Olivia Pope’s portrayer to be her own protagonist.

What do you feel like you’re still reckoning with about race in America?

One of the things that I realized is that we have this mistaken assumption that no one wants to talk about race when actually a lot of people do, and another thing that I realized is that a lot of them are white. Our discussions around race in America are often framed around people of color and more specifically Black people. I thought that a lot of the submissions would come from people of color, and probably primarily Black people. I continue to be surprised at how many people of all colors have pulled up to the table. Usually, the expectation is that Black people are going to lead the discussion, that Black people will be the focus of the discussion. That was a surprise for me, but also, that’s wrapped up in a revelation for me — Why should people of color be the only ones having this discussion? Why should there be an expectation that to the extent racism is a problem that Black people will solve it? How are people going to solve something that they themselves did not create?

How would you say your approach to reporting on race has changed from when you first started writing about it?

The time that I was hosting “All Things Considered,” something happens in the world, we’re gonna have a conversation about race. There’s this cadre of people that you reach out over and over again, you just sort of know who you’re gonna hear on the radio, who you’re gonna see on TV, who you’re gonna read columns from, right? And when we’re talking about race, the expectation is that we’re gonna talk to Black folks, or maybe we’re looking at Hispanics, but white people get bystander status. That’s sort of changed for me. I’m always now thinking, let’s make sure that there will be full participation from lots of different people. I think that we sometimes ask the question, did race play a role in this? And I think the more apt question is, what role did race play? Because so often it does play a role. I’m more curious, I’m more emboldened, I’m more willing to try to understand what’s happening.

You’ve talked about developing a sense of patience over time with people who you maybe don’t agree with. How?

Just listening. The changes in my life have made it easier to do that because I think I have more time. When you’re hosting a show, you just don’t have time to do that. My kids, they’re young adults, they’re off in the world. But some of it also is just developing a muscle that you use — and you realize, OK, I’m learning things by listening.

Interview with the comedian touches on brushing himself off after bombing as host of the award show and carrying positive energy to his big shows at the Kia Forum in February.

Did you fear, going into this project, having to be one of the Black people leading the conversation on race?

Well, that’s kind of the irony, isn’t it? Ask any person of color if they’ve been in mandatory conversations about race in the workplace. It’s just like they’ll lead or fully participate in that and that can be burdensome, and that can also mask a deeper conversation that probably needs to happen. So yes, I was concerned about that and I tried to take what I have learned and apply it.

One of the things I’ve learned is, there’s usually a cohort of people who feel like they’re marginalized. And often, they’re white. They’re white men who are single dads. And there are all kinds of programs for working parents, but they’re all really aimed at women for whom the juggle is real. But no one is thinking about what it’s like for that dad who only gets to see his kids on the weekend, who is concerned about what happens at 3 p.m. when the latchkey kid is on the way home. Sometimes it’s because they are very conservative, and they’re working in a place where they’re presumed to have a certain kind of politics. And maybe they do, but because of that, they feel like they are an outlier, that they are at the fringe. And so now I look for that, because if they’re feeling marginalized, it might not be articulated, but it is still having an impact on the workplace. It’s still having an impact on the institution.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.