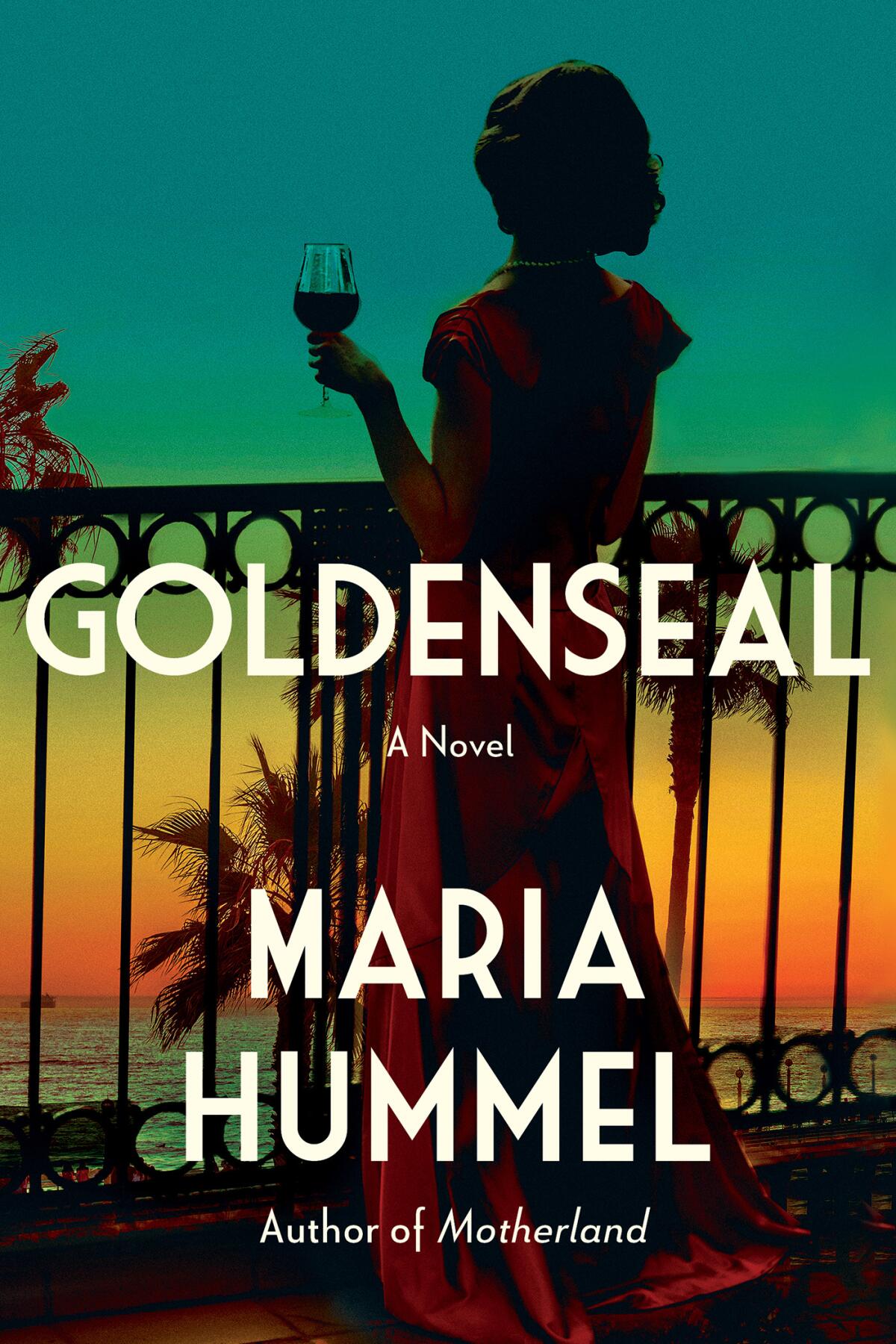

A return to L.A. and a shattered friendship, 44 years later, in Maria Hummel’s new novel

- Share via

Book Review

Goldenseal

By Maria Hummel

Counterpoint: 240 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Maria Hummel has long been interested in finding the flaws in her characters’ narratives. Her first two novels, both set in eras of great upheaval (the American Civil War and World War II), closely follow individuals forced to reckon with how much they know, how that knowledge affects their lives and what they can and should do about it. Her third novel, “Still Lives,” homes in on women’s ownership of their stories, traumas and artistic impulses, and its sequel, “Lesson in Red,” explores female agency, both bodily and intellectual.

Hummel’s new, fifth novel, “Goldenseal,” returns to many of these themes, but the author here narrows her focus to a single friendship between two very different women. The flawed narrative is in this case a relationship, and Hummel’s larger question is how — or whether — it can survive the expectations faced by women, both then and now.

The monikers of killers — the Glamour Girl Slayer, the Goodbar Murderer, the Black Dahlia Murderer, the Golden State Killer — evoke a dreadful poetry that fuels our collective imagination even as we recoil at their deeds.

Lacey and Edith, 70 and 71, respectively, haven’t seen or spoken to each other in 44 years, when, in 1990, they finally reunite. The novel begins with Edith arriving in Los Angeles for the first time since their parting. The city has changed immensely over four decades, and Edith finds it newly fascinating, even though her destination is one of its rare preserved buildings, an old luxury hotel in downtown L.A. (modeled on the real Millennium Biltmore). When she enters, she’s struck with nostalgia:

“[T]he sight of the bar across the lobby, with its glittering bottles, an empty stool. The sound of Italian to her left, a man greeting a woman he clearly admired. The hotel’s heady air of possibility, that you could step from one life into another, just by passing through these doors. It’s like breathing champagne, she used to think, back when she believed that wealth could change her.”

Lacey’s father once owned the hotel, where she now lives as a recluse in a luxury suite. She makes Edith wait downstairs for several hours before allowing her up, in a power move that betrays Lacey’s sense of powerlessness. After all, she’s the one who stayed put, her life dwindling to a bookcase full of alternate realities she can explore; Edith, on the other hand, left L.A. and became a headmistress at a private school. This is one of the great divides between them: not only the choices they made but also the choices they each thought they had access to.

During Edith’s long wait in the hotel lobby, readers are treated to Lacey’s backstory, including her early life in Prague, her parents’ decision to immigrate to New York, her father’s first hotel there, her mother’s temporary abandonment and her fateful meeting with Edith at summer camp, when both girls are on the verge of adolescence. What remains mysterious, however, is the rupture between them, the reason they went from the fastest of friends to strangers with diverging narratives of what went wrong.

Once Edith and Lacey are finally in the same room, the novel’s quiet but effective tension ramps up as they begin to tell each other about what has happened in their lives since last they were together before finally beginning to unspool the stories of what tore them apart. Much of the novel circles their lengthy conversation, but we are largely confined to Lacey’s point of view, privy to her thoughts but not Edith’s. This transparency of one character and obfuscation of another is fitting, since Edith has always been somewhat mysterious to Lacey, her difficult upbringing kept mostly private, her desires often left unspoken.

The 95 contributors to our Ultimate L.A. Bookshelf agreed on many essential books. Here are the 26 best of the best, each receiving at least 7 votes — ranked

It becomes slowly apparent that at the center of the women’s feud is, ostensibly, a man: Cal, who was Lacey’s husband until his death in a plane crash. “Goldenseal‘s” premise is based, Hummel writes in her afterword, on Sándor Márai’s “Embers,” which similarly follows two men meeting four decades after an event that tore their friendship apart. This event involves a woman who, Hummel writes, “is not quite real. Instead, she is the emblem of their greatest passions — to love her as she was — and their most colossal failing: to love each other.” Hummel flips the script, tracing the pain to Edith and Lacey’s fundamental misunderstanding of each other’s wants, as well as different beliefs about the power of female friendship.

Edith once wrote a script “about a friendship. Two girls, one rich, one poor, in a frontier city, facing life together.” She tells Lacey that perhaps it was the only story she had to tell, the only one she wanted to tell. Lacey refutes her: “No, I think you wrote the script because you knew that true, devoted friendship between women is a fantasy that life dismantles. No matter how strong we are, how hard we love, life is stronger still. True friendship could only exist in the dream world where you conjured it.”

Many women today would disagree with Lacey’s bitter outlook, but she is a product of a time when her selfhood was intertwined with her ability to marry well, support her husband’s ambitions and have children. Hummel draws her sympathetically, empathically, even as she proves through Edith’s life trajectory that other choices were possible.

“Goldenseal” is a novel about agency and friendship whose questions reverberate far beyond its two protagonists and their particular time and place. Haunting and tragic, it nevertheless lands on a hopeful note. “I think people grow up many times. Not just once,” Edith tells Lacey at one point, and although the statement refers to both characters’ younger days, the conversation in which it comes up is another moment of growth — much belated, perhaps, but valuable nevertheless.

Masad is a books and culture critic and author of “All My Mother’s Lovers.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.