Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Maybe it was the continued rude health of indie bookstores in 2023, or perhaps a millennial fascination with the pop antiquities of the pre-smartphone era. Or maybe it’s just Mom and Dad Rockers desperate to reel in the years with the gods of their youth. For whatever reason, this year has turned out to be a banner publishing moment for musical giants who until now have not been graced with the full-dress books they deserve — some rigorously researched deep dives, other chatty memoirs or anthologies, many of them illuminations of life and art in urban milieus with all their messy interactions.

Our critics and reporters select their favorite TV shows, movies, albums, songs, books, theater, art shows and video games of the year.

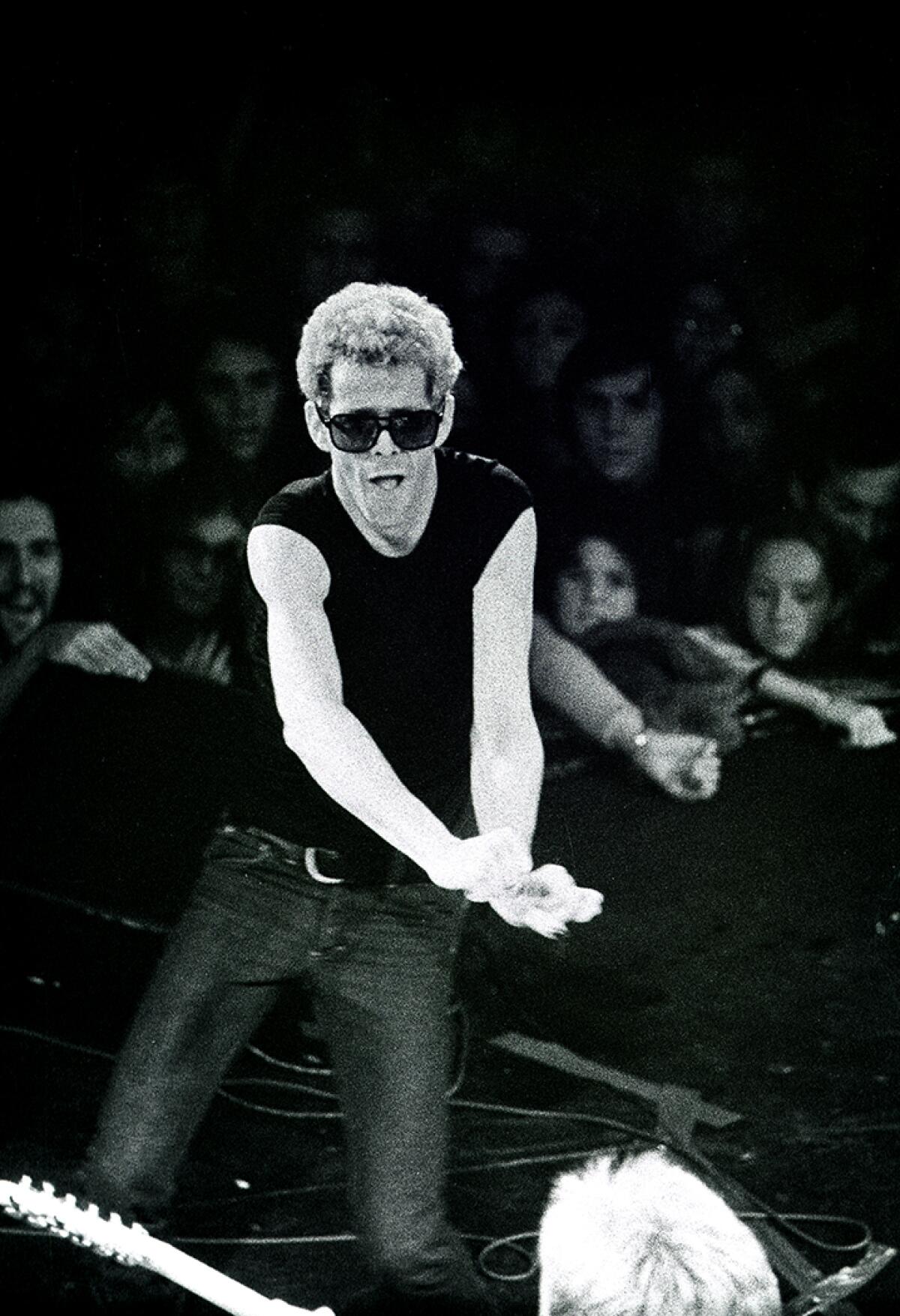

Among the ill-served icons getting their propers in print this year is Lou Reed: New York’s leather prince, the street poet who launched at least three musical genres with his band the Velvet Underground, a lodestar for gender fluidity long before anyone else bothered to write songs about LBGTQ+ and the subculture that nurtured it. Before Will Hermes’ riveting biography “Lou Reed: The King of New York,” the artist’s biographers have tended to be either mean-spirited or bone-dry, glossing over the rough magic of Reed’s inner life.

Three contributing critics pick their best fiction of the year, including work by Victor LaValle, Ed Park, Lauren Groff, Yiyun Li and Tania James.

Hermes, a veteran music critic, has written what will surely be the definitive Reed biography for years to come, a complete portrait of this inconstant, erratic genius, the most eloquent voice of the marginalized during the Nixon era. An elegant prose stylist with a sharp critical eye, Hermes appears to have scared up everyone alive whose life intersected with his subject. And he embraces the contradictions of a musical empath who could be heartless and malicious, tender and vulnerable to friends and lovers — a great bully poet much like Reed’s literary hero and mentor, Delmore Schwartz.

Hermes skillfully twines together the many strands of Reed’s singular life — a benumbing suburban childhood, electroshock therapy, heroin addiction and artistic flowering at the feet of Schwartz and the Beats. Providing fresh stories at every turn, he is particularly adept at conjuring the meth-enabled swirl of Andy Warhol’s Factory universe and Reed’s attachment to the Pop artist, his beloved mentor and bête noir. This is the best biography of a composer since Alex Ross’ 2020 book “Wagnerism.”

One of Reed’s most talented acolytes graced us with a memoir this year. Thurston Moore hit New York as a 14-year-old Reed fanatic in the late ‘70s, right before his idol’s old, weird downtown was forever lost and Wall Street money moved in. Into this liminal space emerged the squalling, post-punk deconstructions of the No Wave movement: saxophonist James Chance and his Contortions, singer-poet Lydia Lunch and, most crucially for Moore, composer Glenn Branca, whose ear-bleed guitar symphonies alerted the Connecticut native to the beauty of Loud. He would harness that volume with his avant-rock band Sonic Youth for 30 years. Moore has a lot of great stories to tell, and he does so engagingly in “Sonic Life,” the tale of a record collector geek made good, a seeker after new sounds who in turn became a key architect of experimental rock in the two decades that followed.

In “Sonic Life” Moore, a suburban outcast like Reed, becomes a pilgrim in search of transcendence through noise and muscles his way into an East Village tempest of brash risk-taking. He meets future bandmates Kim Gordon and Lee Ranaldo. Sonic Youth pulls the throttle all the way out: Moore threads drumsticks into his guitar strings, Ranaldo utilizes an electric drill onstage, Gordon barks out her bold feminist anthems on the seductions of consumer-driven desire. Moore has set it all down, and his book is an engaging memory piece through a golden era of busted toilets and secondhand smoke that now seems as distant as Montparnasse in the 1920s. If you’re looking for juicy bits about Moore and his ex-wife Gordon, you mercifully won’t find it here. He keeps that part of his private life to himself.

Winning the box office, playing record-setting concert tours, rallying striking unions, shaking up TV: Women ruled pop culture in 2023.

While Sonic Youth was cultivating a following on the margins, another downtown scenester was hitting dance clubs like Paradise Garage and Danceteria with designs on something bigger. As a young Michigan exile, Madonna Ciccone found her people in these spaces, and when she insisted DJs spin her record “Everybody,” the fuse was lit. Mary Gabriel’s comprehensive biography “Madonna: A Rebel Life” can be read as the uptown analogue to “Sonic Life,” as this force of nature quickly outgrows New York clubland and in a few short years enters the pop icon pantheon.

Gabriel has done her homework, giving equal weight to Madonna’s private and public selves in a sprawling survey that offers a strong argument for Madonna as a sound-and-vision innovator every bit as crucial as David Bowie. But you have to really care about her relationships with Sean Penn and Warren Beatty to get there.

Decades before Madonna lit up the New York night, Ella Fitzgerald had audiences standing on their seats at the Savoy Ballroom as the singer for Chick Webb’s swing band, a powerhouse vocalist who had to overcome her “pretty plain looks” before she became the 20th century’s tower of song. In her excellent biography “Becoming Ella Fitzgerald,” Judith Tick makes a compelling case for Fitzgerald as a modernist innovator. Promoters and managers told her to stick to one marketable sound, but that wasn’t an option, as Fitzgerald contained multitudes: novelty songs (her self-penned 1938 hit “A Tisket-a-tasket” put her on the map); classic recordings of the Great American Songbook; and the expertly knotty ululations of her scat singing in the bebop era — a genre in which Fitzgerald became the acknowledged master.

Twenty-eight years after Fitzgerald recorded her 1945 hit “Flying Home,” a record that placed scat singing front and center in popular music, Sly Stone was recording his own half-whispered version of scat live in a Sausalito studio. It would become the vamp-out to 1973’s “If You Want Me to Stay,” the last big hit for Sly and his band, the Family Stone.

Alex Edelman’s ‘Just for Us,’ the genius of Stephen Sondheim and a Tony Award for the Pasadena Playhouse were among the highlights of Los Angeles theater in 2023.

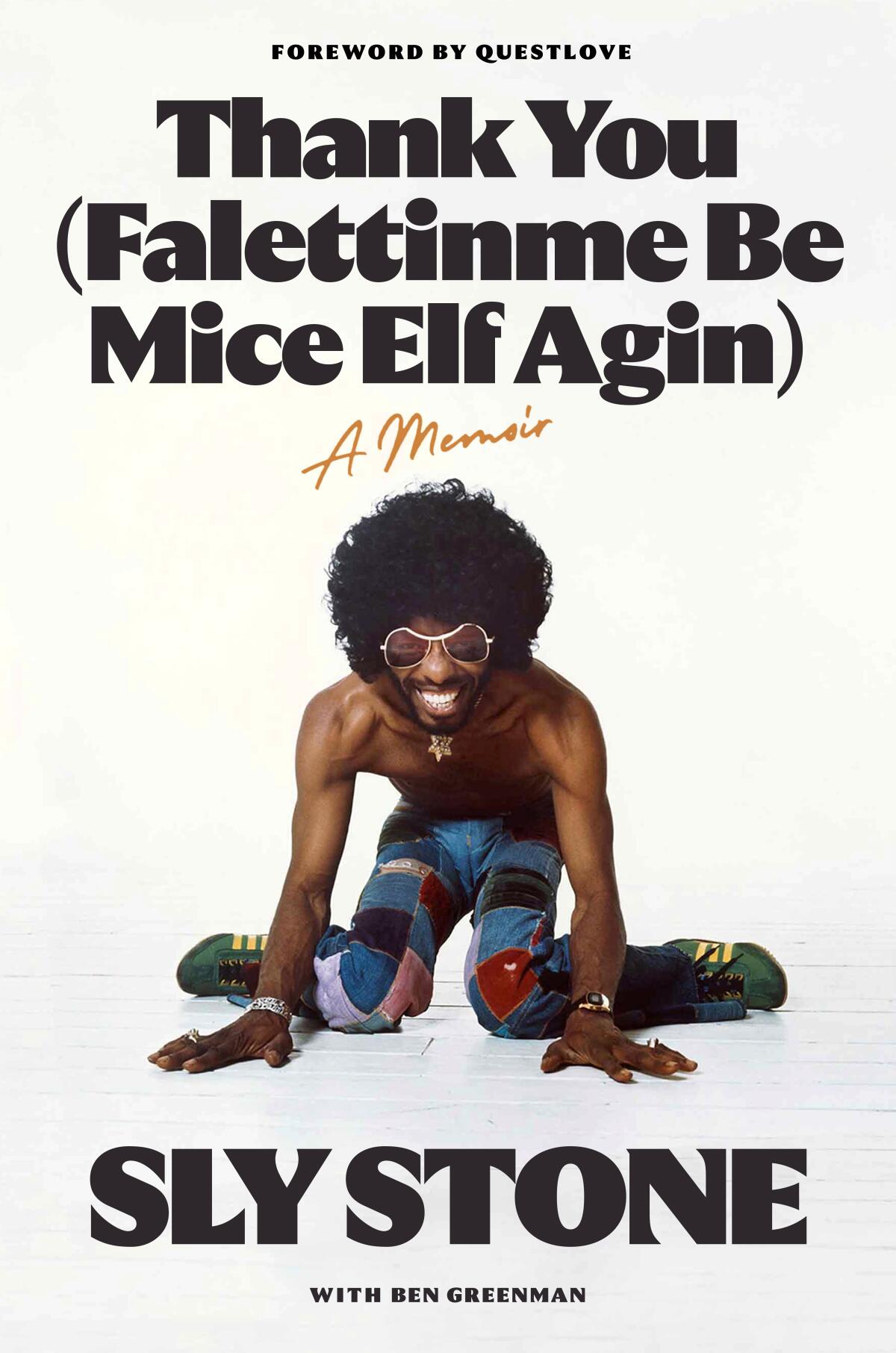

Stone fans have been waiting a long time for the reclusive singer to finally break his silence about his life and career. While his memoir “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)” offers up its share of gonzo tales involving drugs, guns and pet baboons, the erstwhile superstar, 80, provides only tantalizing crumbs of real insight into his messy life. Still, there are some ripping anecdotes (baboons!), and origin stories behind “Stand!,” “Everyday People” and Stone’s other funky one-world anthems.

Perhaps Stone surmised that it’s best to keep his mystique alive, as opposed to expounding on his life at great length in the fashion of Barbra Streisand’s “My Name is Barbra.” Alas, no one has ever told this to the countless fanboys (yes, they are almost always boys) and academics who continue to write books about Bob Dylan, coming at the Nobel laureate from every conceivable angle. And yet, somehow, this year has brought something entirely new: A lavish, glossy scrapbook with material provided by Dylan himself.

“Bob Dylan: Mixing Up the Medicine” is a stunning visual trip through the artist’s life and art as revealed via Dylan’s own ephemera and Zimmerman-adjacent mementos from friends and musicians. Published in conjunction with the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, Okla., this immaculately designed coffee-table confection also features a collection of informative essays from Lucy Sante, Greil Marcus, Ed Ruscha and others. They provide context for what we’re seeing, which is quite a bit — grade school class photos, Dylan’s notebooks, manuscripts and legal pads and, yes, even photos that this Dylan freak has never seen before.

2023 is the year of the star-studded gift book, with memoirs and biographies covering rockers, auteurs, poets, controversial executives and, yes, Julia Fox.

Which reinforces a couple of valuable lessons from this year’s joyful glut of music tell-alls. First: While they’re no substitute for the brilliantly written, category-killing, milieu-rich biography, no format is inherently better or worse at delivering the goods. And second: There’s always something new under the sun.

Weingarten is the author of “Thirsty: William Mulholland, California Water, and The Real Chinatown.”

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.