Why there’s no such thing as an antiwar film

- Share via

Review

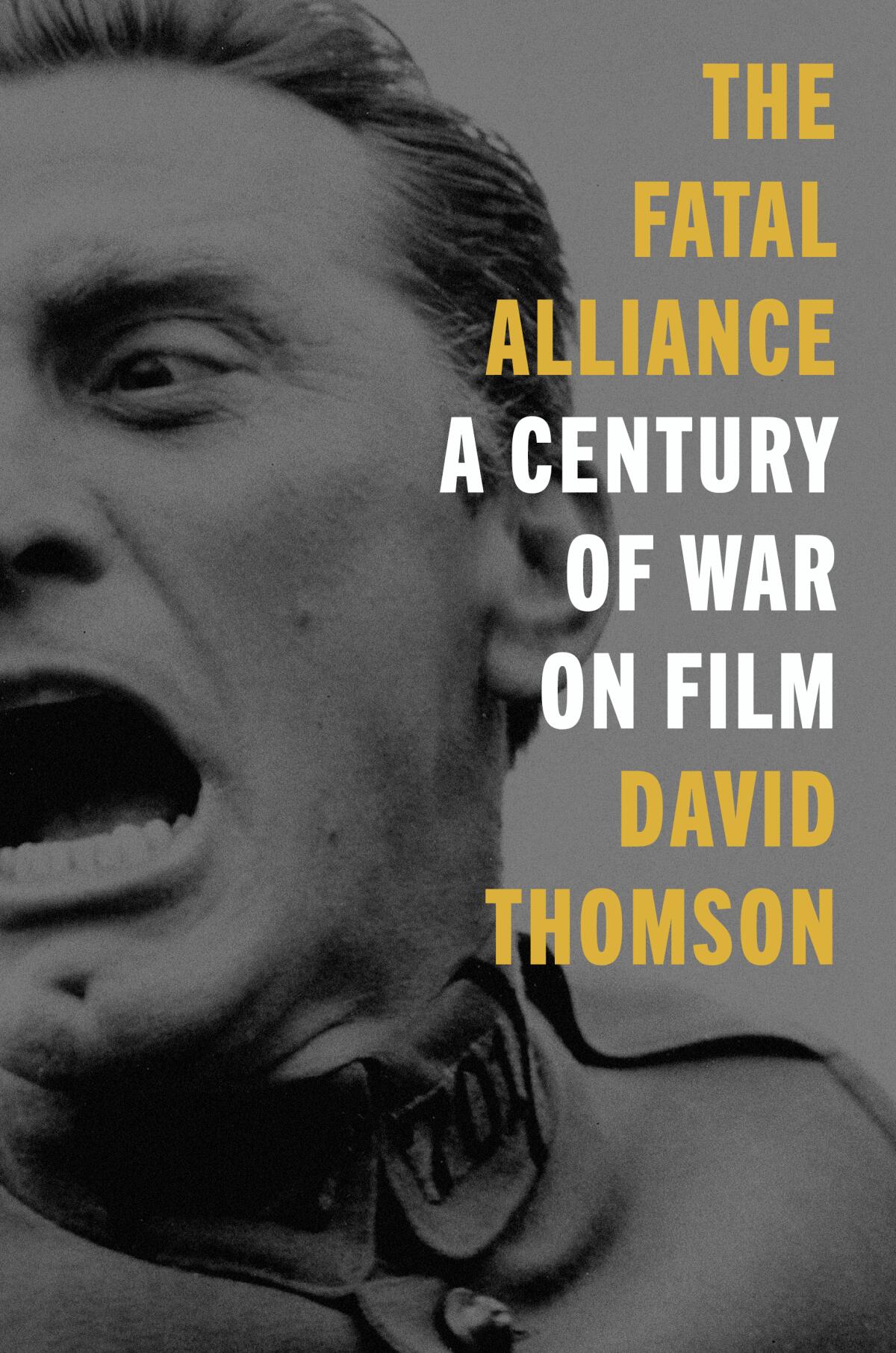

The Fatal Alliance: A Century of War on Film

By David Thomson

Harper: 448 pages, $35

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

“I doubt there is any such thing as an antiwar film,” veteran movie critic David Thomson writes in his new survey of war movies, “The Fatal Alliance.” “In the dark, whatever the official motive or the orders, we go to war for excitement.”

Those are fighting words, but they’re worth debating — especially now, as the headlines demonstrate how badly the antiwar side is doing. So many of the war movies we most admire pay lip service to the notion that war is abominable and to be avoided, but only while delivering the thrill of witnessing combat.

The opening D-day sequence of “Saving Private Ryan” and the climactic mad dash of “1917” are rightly praised for their authentically rendered brutality. But the chaos is typically part of a larger narrative designed to provide reassurance that war delivers victory and a sense of order: The soldier is rescued, the battlefield directive is successfully fulfilled. In that light, those “gritty” and “authentic” war films may be more of a guilty pleasure than any MCU spectacle.

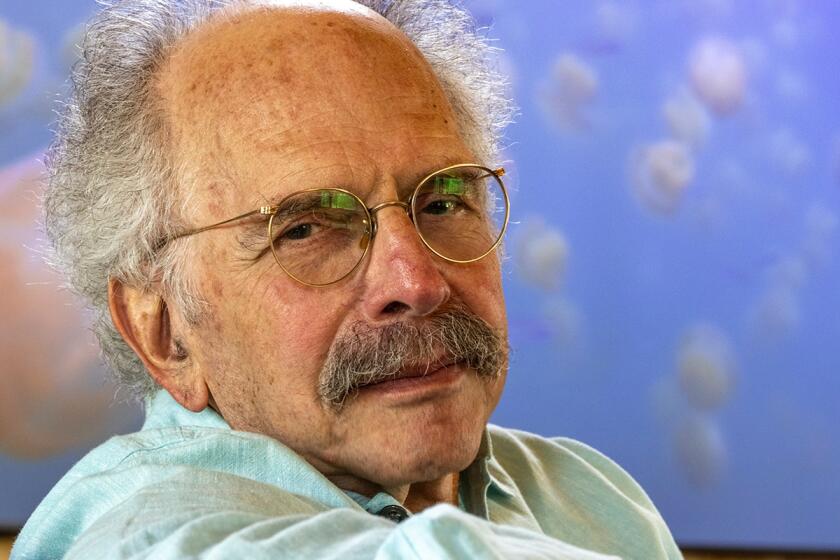

Thomson, the author of dozens of books including “The Biographical Dictionary of Film,” binges on “Ozark” and Godard but finds “L’Avventura” a drag.

This paradox is Thomson’s central concern throughout the book, but that doesn’t mean “The Fatal Alliance” is a book-length guilt trip. Thomson deeply admires many entries in the genre — he notes he’s watched “Black Hawk Down” six times — and has a keen eye for moments that undermine its more propagandistic conventions. But he’s also persistently, thoughtfully questioning what filmmakers intend, what conversations they’re accidentally stepping into and how we as moviegoers are implicated as war-story consumers.

Thomson is exceedingly well-equipped for the job: Since 1975, he has been publishing and updating his essential “Biographical Dictionary of Film,” which is thick with pungent, opinionated surveys of filmmakers and actors. (Its latest edition, the sixth, was published in 2014.) And he’s long been mulling questions of what war movies tell us, or withhold. There’s a fine essay on war movies in his 2012 book, “The Big Screen,” for instance, contemplating how they ratify history, obscure the worst carnage and serve as imperfect metaphors “for uncertainty and disorder.”

Thomson’s organizing principle in “The Fatal Alliance” is chronological, starting with films made during and about World War I and ending in the present day. Almost immediately, he notes, Hollywood found a successful formula for the war film: Blend combat and romance. Charlie Chaplin’s 1918 short “Shoulder Arms” featured a clumsy doughboy rescuing a French girl while on a secret mission; King Vidor’s 1925 epic “The Big Parade” braided battle scenes and courtship rituals.

“A genre was established,” Thomson notes, but at a cost. Chaplin’s bumbling humor helped create a “public [that] beheld the disaster with a relative tranquility that we now find hard to grasp or forgive.”

Peter Biskind’s movie history ‘Easy Riders, Raging Bulls’ was a classic. His new TV history, ‘Pandora’s Box,’ is not. It’s rarely insightful, but never boring

Thomson does identify movies that unsettle this sense of comfort, such as Stanley Kubrick’s “Paths of Glory,” a savage critique of the officer class, or Terence Malick’s “The Thin Red Line,” which makes war into an abstraction of fear and uncertainty, or Gillo Pontecorvo’s “Battle of Algiers,” still the standard-bearer for films about anti-colonial resistance since its release in 1966.

Even in those cases, however, war movies more usually represent history as written by the winners. “Countless war films have an imprimatur whereby the outcome of the war is reinforced by the stance of justice we have picked up, allied to a feeling that the institution of cinema stands firm behind the meaning of the story,” Thomson writes. Which is a long way of saying that war movies are, when you come down to it, propaganda.

Though “The Fatal Alliance” has an arc and a central argument, it’s not as user-friendly a genre survey as a moviegoer could hope for. Nobody comes to Thomson for cozy listicles of “top five problematic Vietnam movies.” But his career-long dedication to writing pithy biographical encyclopedia entries means the book seems to leap habitually from film to film without filling out its assertions. No sooner has he called out the subtle provocations of “The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp” or “Gallipoli” than he’s off to visit Private Ryan, the River Kwai and a dozen more less-familiar war stories.

When he slows down, though, “The Fatal Alliance” can be bracing and surprising. The book’s best chapter is a more patient meditation on Mel Gibson, Thomson’s (well, everyone’s) complicated relationship with his work, and how films like “Braveheart” and “Apocalypto” crystalize the war movie’s contradictions and dangers: “This is Trumpian cinema, and you can feel his contempt for us and shudder at the power it may attain.”

Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert inspired a generation of future film critics. Matt Singer returns the favor in ‘Opposable Thumbs,’ his bio of the odd couple.

The deepest trouble with war movies, Thomson suggests, is that they warp how we experience and understand the real thing. What do we miss, or misunderstand, when we look at Gaza or Ukraine through the filters taught to us from war movies, with their easy platitudes about valor and patriotism? What kinds of heroism are we pining for, and does that urge come at the expense of seeing war’s essential chaos plainly?

“The artifice and corruption of the movies has compromised the plain intensity of war,” Thomson writes. “The Fatal Alliance” is unlikely to transform our appetite for the thrill of war movies; let’s hope, at the least, it will make us a little more uncomfortable in our seats.

Athitakis is a writer in Phoenix and the author of “The New Midwest.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.