- Share via

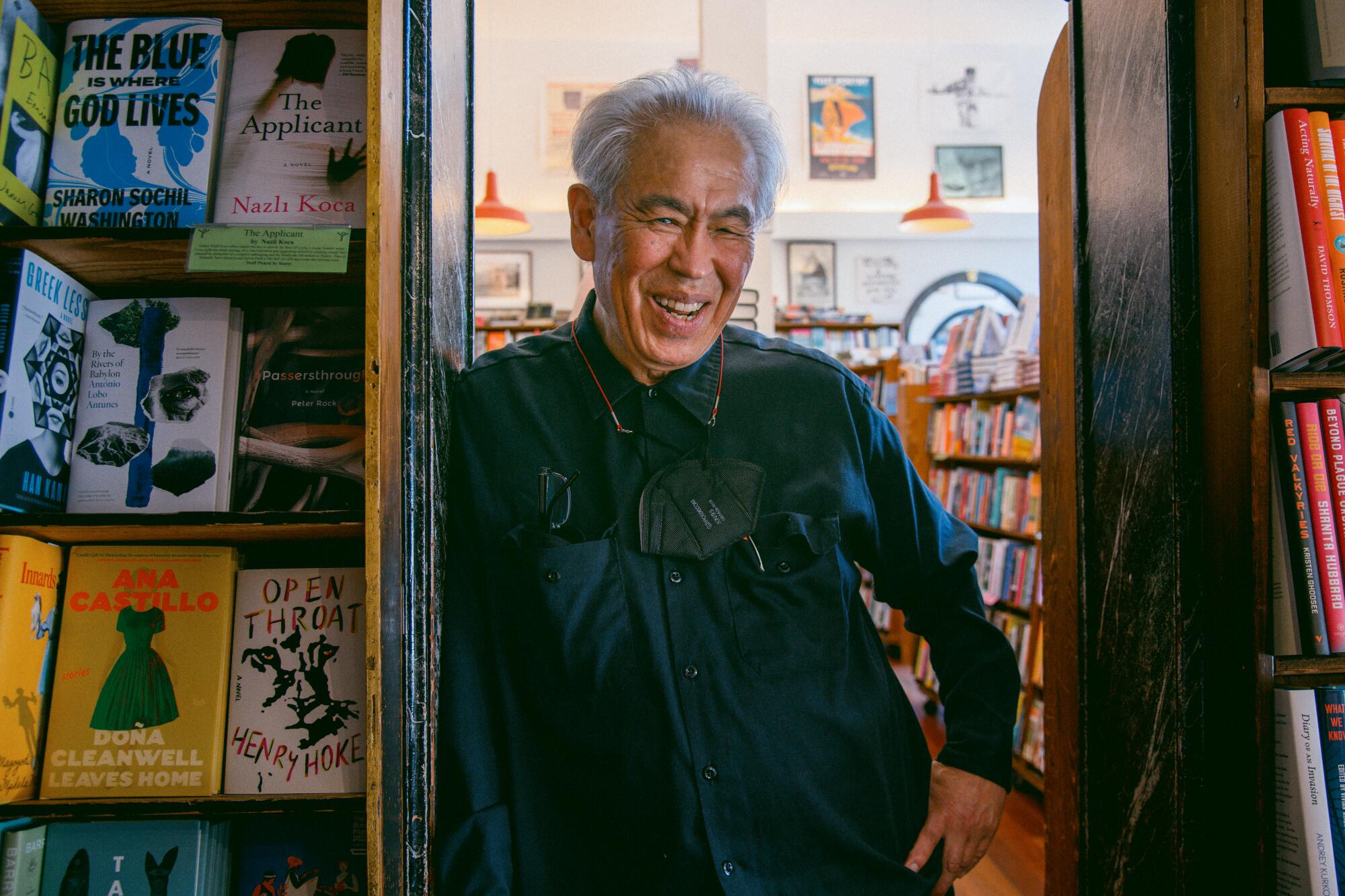

Paul Yamazaki did not grow up loving books. As a teenager in the San Fernando Valley, he was directionless. “I was the despair of my parents,” he recalled. “I was an incredibly poor student and got incredibly poor grades.” Today, at age 74, Yamazaki is one of the literary world’s most respected and beloved book buyers. He has worked at the legendary City Lights bookstore in San Francisco for more than half a century — 53 of the store’s 70 years. The association runs so deep that Yamazaki, a childhood Dodgers fan, likens himself to the team’s late longtime manager. “I’m the Tommy Lasorda of City Lights,” he said with a laugh.

This fall, for all his achievements in championing books and reading, Yamazaki will receive the prestigious Literarian Award for Outstanding Service to the American Literary Community, presented annually by the National Book Foundation.

The 65 essential bookstores of L.A. County: Their vibes, customers, books and testimonies from customers, writers and owners.

Fittingly, Yamazaki’s life story is like something out of a sprawling, eventful novel, with chance encounters and strokes of good fortune guiding him toward a path of fulfillment.

In an interview at director Francis Ford Coppola’s Cafe Zoetrope — Yamazaki’s “home away from home,” just down the hill from City Lights in North Beach — Yamazaki reflected on his unlikely journey.

He describes his upbringing in Van Nuys as “very middle class.” His father, a pediatrician, was a decorated World War II veteran who had served in the same infantry division as Kurt Vonnegut; like the author, he was captured during the Battle of the Bulge and spent time in a German prison camp. Yamazaki’s mother was the daughter of a well-to-do wholesale produce broker.

Both his parents were Nisei — second-generation Japanese Americans — and both graduated from UCLA. Yamazaki’s family was not politically active, but unlike many suburbanites in Eisenhower’s America, his parents were progressives. “They voted for Adlai Stevenson,” Yamazaki said, “but they thought he was too moderate. And they voted for Jack Kennedy, but they thought he was far too conservative.”

What broke Yamazaki out of his sleepy childhood, he said, was music. Thanks to a local FM radio show, Yamazaki was introduced to Chicago blues. On Friday and Saturday nights, after his shift as a busboy ended at Ah Fong in Encino, Yamazaki would hop in his 1954 Chevy Bel Air and head to the Ash Grove, the celebrated roots music venue on Melrose Avenue, and take in such musicians as Willie Dixon, Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf. “It was an incredible musical education,” Yamazaki said. It was also an awakening.

“I wanted to get out of the Valley,” Yamazaki said. So he set his sights on San Francisco, famous as a hotbed of postwar youth culture. Despite his less-than-stellar academic record, he was accepted by San Francisco State University. “The fact that I got in was kind of a miracle,” Yamazaki said, laughing.

The newcomer didn’t quickly fit in. Shortly after arriving in San Francisco in 1967, Yamazaki remembers, he took a stroll along Haight Street, then the city’s epicenter of hippie life. “Here’s this suburban kid wearing a yellow London Fog jacket and wingtips,” he recalled. “I couldn’t look more square!” Then one day, in Aquatic Park along San Francisco Bay, someone handed him a leaflet for a Black Panther Party benefit at the Surf Theatre. The event included a screening of the just-released political film “The Battle of Algiers.”

“I didn’t know what the Black Panthers were,” Yamazaki said. “I didn’t know what the Surf Theatre was. And I certainly didn’t know what ‘The Battle of Algiers’ was.” None of that mattered. “For whatever reason,” he said, “I decided to go.”

Santi Elijah Holley’s ‘An Amerikan Family: The Shakurs and the Nation They Created’ tells the full story of the radical Black family that bred late rapper Tupac Shakur.

It was one of the times in his life when he was, as he put it, “really, really f— lucky.” The event planted a seed in him. It got him thinking more about the state of the world, about the war in Vietnam. Before long, he was attending Bay Area antiwar rallies and sit-ins — and getting arrested. He wound up in jail for months.

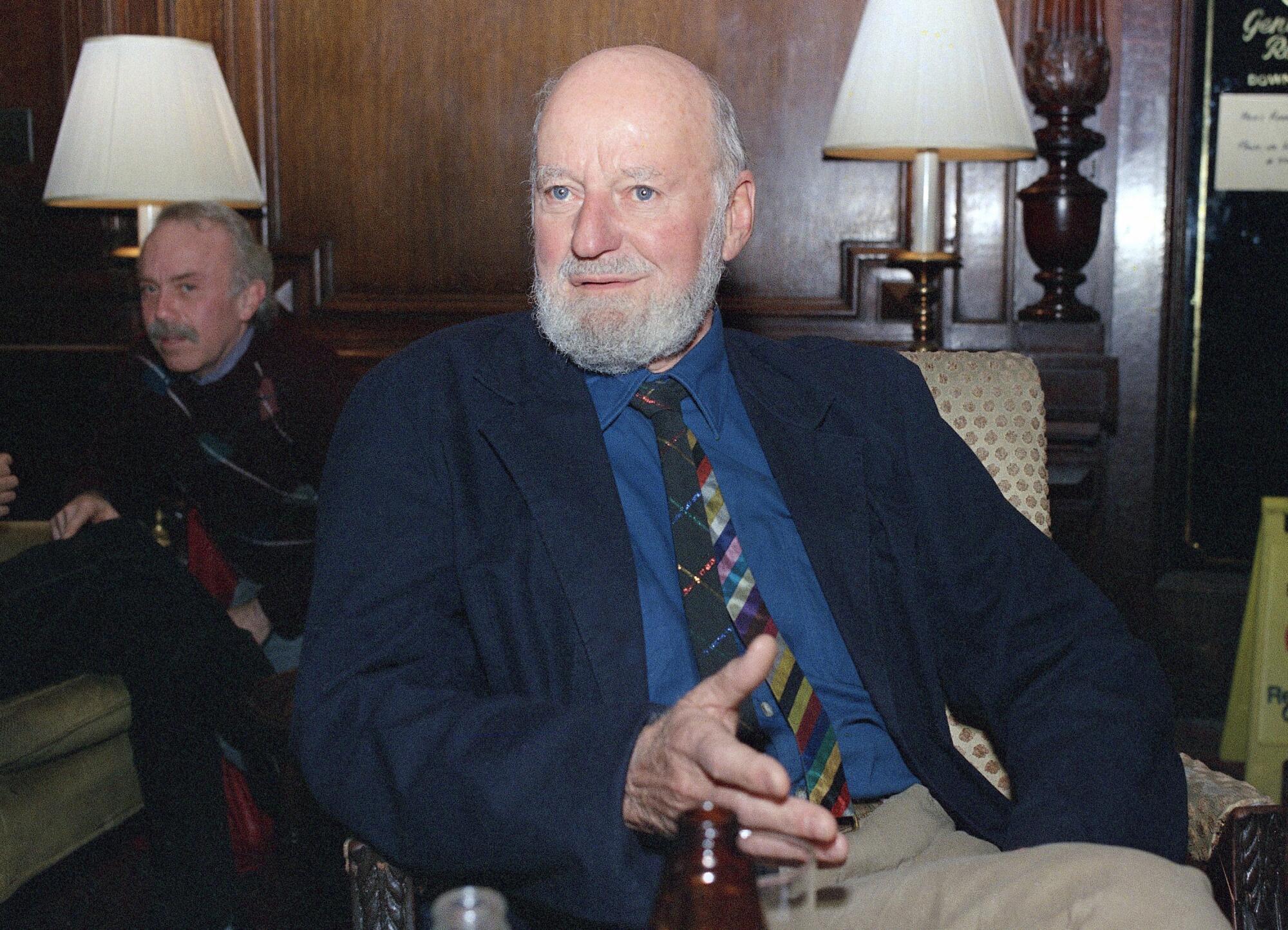

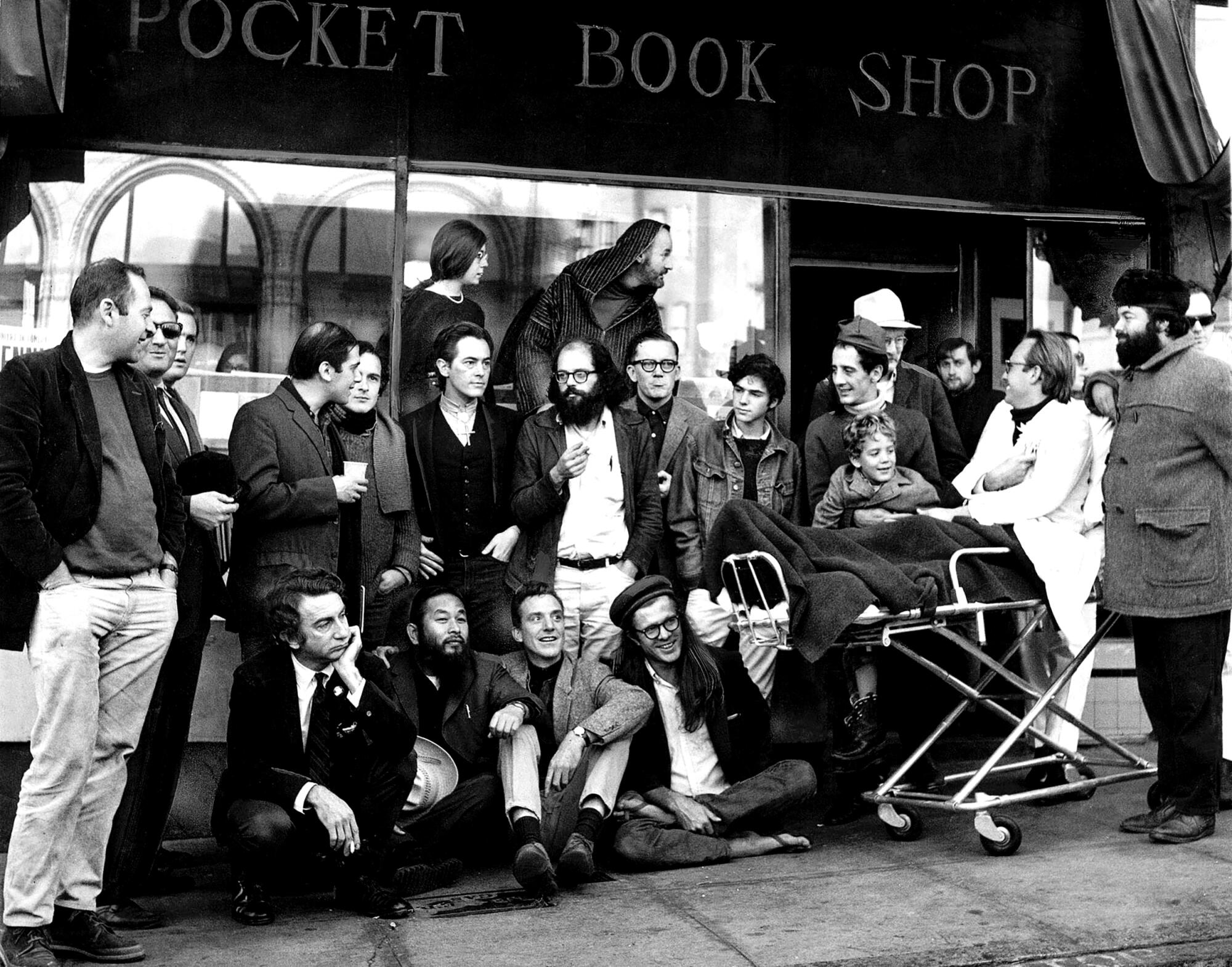

But then, in 1970, Yamazaki got lucky again. Francis Oka, a young activist he had befriended, worked at City Lights. Lawrence Ferlinghetti, the poet and World War II veteran-turned-pacifist who had co-founded the store with Peter Martin in 1953, had made it a haven for independent thinkers; its status was cemented in 1957 after Ferlinghetti and bookseller Shigeyoshi “Shig” Murao were tried — and acquitted — for publishing and selling the Beat poet Allen Ginsberg’s “obscene” epic “Howl.”

Oka told Ferlinghetti and company about Yamazaki’s situation: the protester from Southern California had been in jail for roughly 100 days, but if he secured a job, his six-month sentence would be cut short.

“They had no idea who the f— I was,” Yamazaki said. “All they knew was that Francis recommended me. It’s something that I fell into. I was hired while I was still in jail.”

Being behind bars opened Yamazaki’s eyes. This “sheltered Japanese American kid,” as he called himself, learned not to make “blanket judgments based on class, ethnicity or roles.” Working as a day laborer on the city’s docks also made him empathize with those who endured brutal working conditions. “You got the worst jobs, like in a hold of a ship unloading 50- to 100-pound pallets of stinking Argentine horse hides,” he recalled. “It was so bad that my roommates at the time — they made me disrobe at the bottom of the stairs and put my clothes in a plastic bag.”

He also developed a fondness for simple, humble clothes. For decades, Yamazaki has worn an affordable, largely black uniform: Dickies shirt (buttoned to the top), Dickies pants and thick-soled orthopedic shoes. Around his neck, below his silver hairline, is a lanyard from the Library of Congress that holds his keys. On it is a quote from Thomas Jefferson: “I cannot live without books.”

When Yamazaki started at City Lights, the job was far from glamorous. For a couple years he worked as a packer, sending off books from the store’s publishing arm, City Lights Publications, at nearby 1562 Grant Ave. But spending time with Oka broadened his horizons — and his reading.

“Even though he was only a couple years older than me, he became a real mentor,” Yamazaki said. “He was so clearly more mature and wise.” Oka turned his acolyte on to authors outside the Beat movement, including Frantz Fanon and Aimé Césaire — “the first crack in the door to this vast world of literature beyond what was produced here.”

Sesshu Foster celebrates Amy Uyematsu, a pioneering and politically active Japanese American poet, who died Friday at 75 — and never stopped fighting or writing.

Yamazaki and Oka became roommates, living on a houseboat across the Golden Gate Bridge in Sausalito. Yamazaki would hitchhike to work and back. “It was kind of a goofy thing to do,” he said about the living arrangement. It came to an end when Oka died in a motorcycle accident.

Distraught and at a loss, Yamazaki shacked up at City Lights’ Grant Avenue office for a few months, his sleeping bag on the floor. “I had no place to go,” he said. “Everybody was so generous.”

The 1970s were a heady time for City Lights, a bohemian hangout. Regular visitors included Ginsberg and fellow poets Amiri Baraka, Gregory Corso, Bob Kaufman and Gary Snyder. Because the Keystone Korner jazz club was close by, the likes of Max Roach and Cecil Taylor would come in to browse the shelves between sets. The bookstore was open until 2 a.m. on weekends, and occasionally a stray patron could get locked in overnight. (These days City Lights closes at 10 p.m., a loss for night owls who, pre-pandemic, could wander in until midnight.)

For more than a decade, as he put it, Yamazaki was “a part-time reader working in a bookstore.” It took a crisis, in 1982, for him to become the book buyer. “They had no choice,” he said of the store’s managers. “The business was literally at the point of failure.”

What few remember is that by that point City Lights was, in Yamazaki’s words, “an embarrassment,” having strayed from its roots due to a change in management. “We wouldn’t have, for example, any [Alain] Robbe-Grillet, but we’d have all these Garfield the cat books. It’s hard to describe how atrociously bad we were — and how disappointed people were.”

Yamazaki credits Nancy Peters, who became co-owner of the store in 1984, for righting the ship. “If it weren’t for Nancy,” he said, “City Lights would be this nice memory.” Today, it owns the building it occupies — a rarity in the book world, where many stores are beholden to landlords.

Yamazaki, too, has played a major part in reinvigorating City Lights, building on the mission Ferlinghetti established decades ago to make the store, as Yamazaki said, “a beacon of critical thought and the best of contemporary literature. … What we’re trying to do is bring more people into the full awareness of how deep and rich culture is.”

Elaine Katzenberger, the operation’s executive director and publisher, said, “City Lights owes its reputation as one of the most interesting and stimulating environments a reader can find to Paul Yamazaki.” Because of him, she added, the store “provides an environment for readers that is unmatched in its breadth, its rigor and its passionate advocacy.”

Among the books Yamazaki has been proud to draw attention to are Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s “Golden Gulag” and Karen Tei Yamashita’s novel “I Hotel.” He’s also fervently sung the praises of work published by small Bay Area presses, including Heyday, Transit Books and Two Lines Press.

Over the course of his career, Yamazaki has devoted himself to acquiring books one might not find in other shops. Much of the store’s 2,100 square feet of retail space — big enough to showcase 35,000 books on three floors, including a poetry room — is reserved for categories such as African history, class warfare, green politics, muckraking and people’s history.

The activist ethos extends to Ferlinghetti’s hand-painted signs, which hang throughout the store. “Printer’s ink is the greater explosive,” reads one. “Books not bombs,” says another. Taped to the window in Yamazaki’s second-floor office is a sheet of paper that reads, “Trans rights = human rights.”

Yamazaki is rarely at City Lights these days. Like others, he’s kept up his pandemic routine of working largely from home. But he still meets with publishers’ representatives, editors and co-workers at a favorite restaurant in his Ingleside neighborhood and at Vesuvio Cafe, Specs’ and Tosca Cafe, the three North Beach bars that have long hosted City Lights employees.

What Yamazaki values most in his work are conversations. A publisher’s catalog of forthcoming titles might give him a sense of a book, but a talk with an acquiring editor is far more valuable. For decades, he has cultivated such relationships, and many in the industry cherish time spent with the book buyer, his spirited conversation marked by his unrestrained laughter, his self-effacing manner, his gravelly voice and his liberal and gleeful use of profanity.

Some visit San Francisco’s North Beach because it tastes like Italy, and some visit because it howls like the Beat Generation. But the times, they are a-changing.

Approaching age 75, Yamazaki sees no reason to retire just yet. “Despite all the challenges we have in the business,” he said, “there’s so much to be excited about — starting with the emerging authors that we’re seeing, the emerging editors and publishing houses, the emerging booksellers.”

And there is the Nov. 15 ceremony in New York at which he will receive the Literarian Award. Only 18 people have been honored with the prize, including Maya Angelou and Dave Eggers. The first person to receive it was Ferlinghetti, in 2005. Ferlinghetti died in 2021 at age 101.

“I am really, really honored to follow in his footsteps,” Yamazaki said. “City Lights has been my university.”

McMurtrie is senior editor of the San Francisco-based literary journal Zyzzyva.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.