Yet another critic on the Death of the Novel: What he and everyone else are missing

- Share via

On the Shelf

The Novel, Who Needs It?

By Joseph Epstein

Encounter: 152 pages, $26

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Joseph Epstein’s “The Novel, Who Needs It?” is the latest in a rich tradition of hand-wringing about the state of what has become the preeminent artistic form of the last few centuries. For much of its history, the novel has had its honor defended by a who’s-who of literary stalwarts against cultural forces allegedly arrayed against it. Over the centuries these have ranged from sentimental romance writers (per Samuel Johnson) to rationalists like Edgar Allan Poe, the masses who consume TV or those who prefer Michael Crichton.

The problem with these polemics, manifestos and personal theses is that as much as their culprits have changed, they all pretty much make the same arguments, cite the same benefits and even use the same language. Epstein, to his credit, acknowledges the persistence of anxiety over the novel’s health. Citing an entry from 1856 in the Goncourt brothers’ collaborative diary, in which they lamented that the fiction of Poe was “sickly,” “analytic” and “monomaniacal,” Epstein then jump-cuts to a 2014 essay by the novelist Will Self, in which he laments having to watch the art form to which he committed his life die in front of him.

I’m tired of reading about the death of the book.

“The announcement of the Death of The Novel has over the years become something close to a regular event,” he seems to lament, although a few sentences later he writes, “Yet just now talk about the death of the novel has a credibility it has not quite had before.” This reminded me of Tobias Funke in “Arrested Development” telling his wife, Lindsay, that the open relationships he advises his therapy patients to explore “never” work for them but they still “delude themselves into thinking it might … but it might work for us.” No one in nearly two centuries has been able to save the novel … but it might work for Epstein? (Narrator: It doesn’t.)

Just who are the enemies this time around? Epstein has made a modest name for himself as an amiable conservative curmudgeon, a sort of George Will lite, and his antagonists are many: the internet, political correctness, MFA workshops, commercial pressures, graphic novels, therapeutic culture and the supposed rise of vulgarity. To prove that recent novels are diminished by these forces of decline, he quotes from reviews and not the novels, as he not so subtly implies that reading them is beneath him — a strategy so unbecoming of a critic I’m surprised it passed muster with his editor.

Epstein is one of the most prolific literary critics in America, having published 17 collections of reviews, profiles and essays — a preeminent expert on the novel, in other words. And yet, for all his critical acumen (and Epstein can be an astute critic), he isn’t really treading new ground, and when he does it’s in the wrong direction. Many of his points were made nearly three decades ago by another curmudgeon of American letters, Jonathan Franzen, in an essay that struck such a chord with the literary world it was referred to simply as “the Harper’s essay.” Franzen complains that the novel is no longer culturally central, that consumerism strangles an “antithetical product” like a novel, that technology has outpaced the speed of fiction, that we solve all our problems with quick fixes and that — on a more personal note — the world wasn’t sufficiently celebrating his writing.

Reading the Harper’s essay now, it’s hard not to side with James Wood when he remarked that the essay is “incoherent,” oscillating among global pessimism, personal turmoil and tangents about things like how his good manners preclude him from telling his brother, “who is a fan of Michael Crichton, that the work I’m doing is simply better than Crichton’s.” What a tough beat.

His new novel, ‘Crossroads,’ is extraordinary, immersive, even fun. But it makes you wonder what Franzen might accomplish if more were at stake

Like Epstein, Franzen almost gets the point before turning away from it. “The current flourishing of novels by women and cultural minorities,” he concedes, “shows the chauvinism of judging the vitality of American letters by the fortunes of the traditional social novel.” Our literature may even be “healthier” because we’ve disabused ourselves of the need for a monoculture, which was, after all, “an instrument for the perpetuation of a white, male, heterosexual elite.” Maybe life is too multitudinous for any one novel to capture its spirit, he muses, and “perhaps ten novels from ten different cultural perspectives are required now.”

But just as soon as Franzen arrives at this moment of clarity, he also argues that young writers feel “imprisoned by their ethnic and gender identities” and are “discouraged from speaking across boundaries.” He wants his fiction big and diverse and emblematic of an entire culture; none of this “My Interesting Childhood” nonsense that MFAs produce.

Epstein drags Franzen’s complaint, which is at least sincerely about narrative scope, three decades forward and straight into the culture wars. “A writer is no longer permitted,” Epstein declares, though it happens all the time, “to ‘appropriate’ the material of those to whom presumably by rights it belongs.” He goes on to defend the writer Lionel Shriver, who “caused a stir when she rightly complained that the ideologies behind ‘appropriation’ would put an end to all fiction.” Epstein neglects to mention that Shriver made these complaints while donning a sombrero, nor that Shriver spends a good chunk of that speech settling scores with critics who called her novel “The Mandibles” racist because, according to her, “it doesn’t toe a strict Democratic Party line.”

What Epstein, Shriver and Franzen miss is that — setting aside a few high-profile Goodreads pile-ons — hundreds of novels arrive every year filled with characters whose race, gender, sexuality or nationality differ from their authors and no one bats an eye. The problems occur when writers don’t take their responsibility seriously. How can you simultaneously argue that the novel’s power is unsurpassed and then treat the consequences of that power as meaningless?

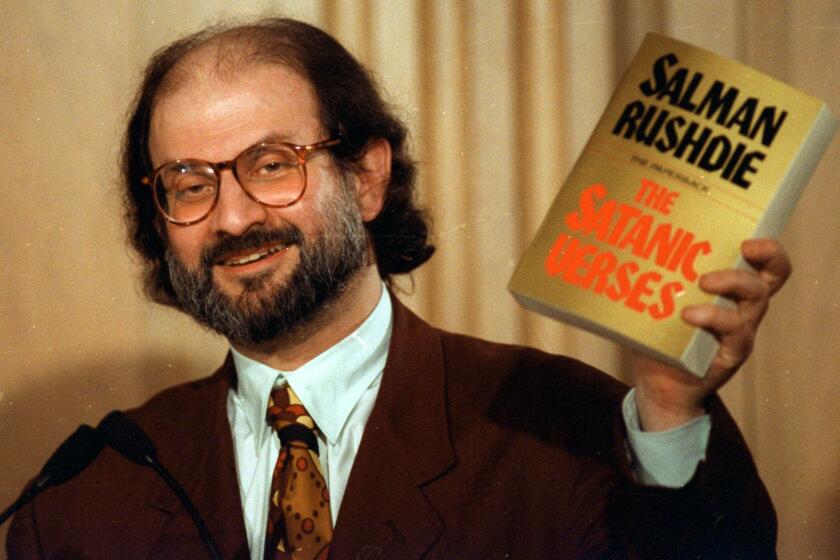

Salman Rushdie was marked for death and celebrated as an icon after writing “The Satanic Verses.” Last week’s near-fatal attack reminds us of the stakes

Whereas for Epstein the stakes of the novel’s livelihood are primarily abstract, for those “cultural minorities” he mentions, the turmoil takes an altogether more menacing shape. The theorist bell hooks notes in an essay on Toni Morrison that few Black women writers are considered “serious.” The pioneering gay novelist Gore Vidal recalls how the publication of his novel “The City and the Pillar” in 1948 was met with “shock and disbelief.” Salman Rushdie very nearly died because his novel “The Satanic Verses” was deemed heretical. These concerns are deeper and more vital to confront than any of the issues raised by Franzen or Epstein, because they have actual stakes. Rushdie, hooks, et al., worked to improve the novel; Epstein and his confreres want the world to change around it.

Maybe the biggest reason of all that Epstein and Franzen — and the Goncourts and Samuel Johnson before them — have been so ineffective at defending the novel is that they’ve been ineffective at defining it. And not for lack of trying: To Epstein it’s a standard-bearer of the right and proper, to Franzen a kaleidoscopic rebuke of pop simplification, to the Goncourts some rearguard defense against the technical age, to Johnson a rejection of sentimentality.

For Epstein, if we lose the novel “we are forced to fall back on the rather sterile concepts and ideas that current-day philosophy and social sciences ... provide.” But what deeper truths does the novel offer to transcend false notions? A great novelist methodically dismantles them, as Epstein points out, but that means the responsibility for the novel’s vitality lies not in readers, nor in critics — especially those who don’t read the books — but in writers. They must work vigilantly to maintain the novel’s health, in part by accurately reflecting life as it is, not as they wish it to be.

In 1884, Henry James wrote that the “only condition” he could think of for the writing of a novel is “that it be sincere.” The novel offers its creator a freedom that “is a splendid privilege,” James continues, “and the first lesson of the young novelist is to learn to be worthy of it.”

Clark is the author of “An Oasis of Horror in a Desert of Boredom” and the forthcoming “Skateboard.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.