In a dark satirical novel, a callow Brooklyn tech bro atones by ... going vegan?

- Share via

Review

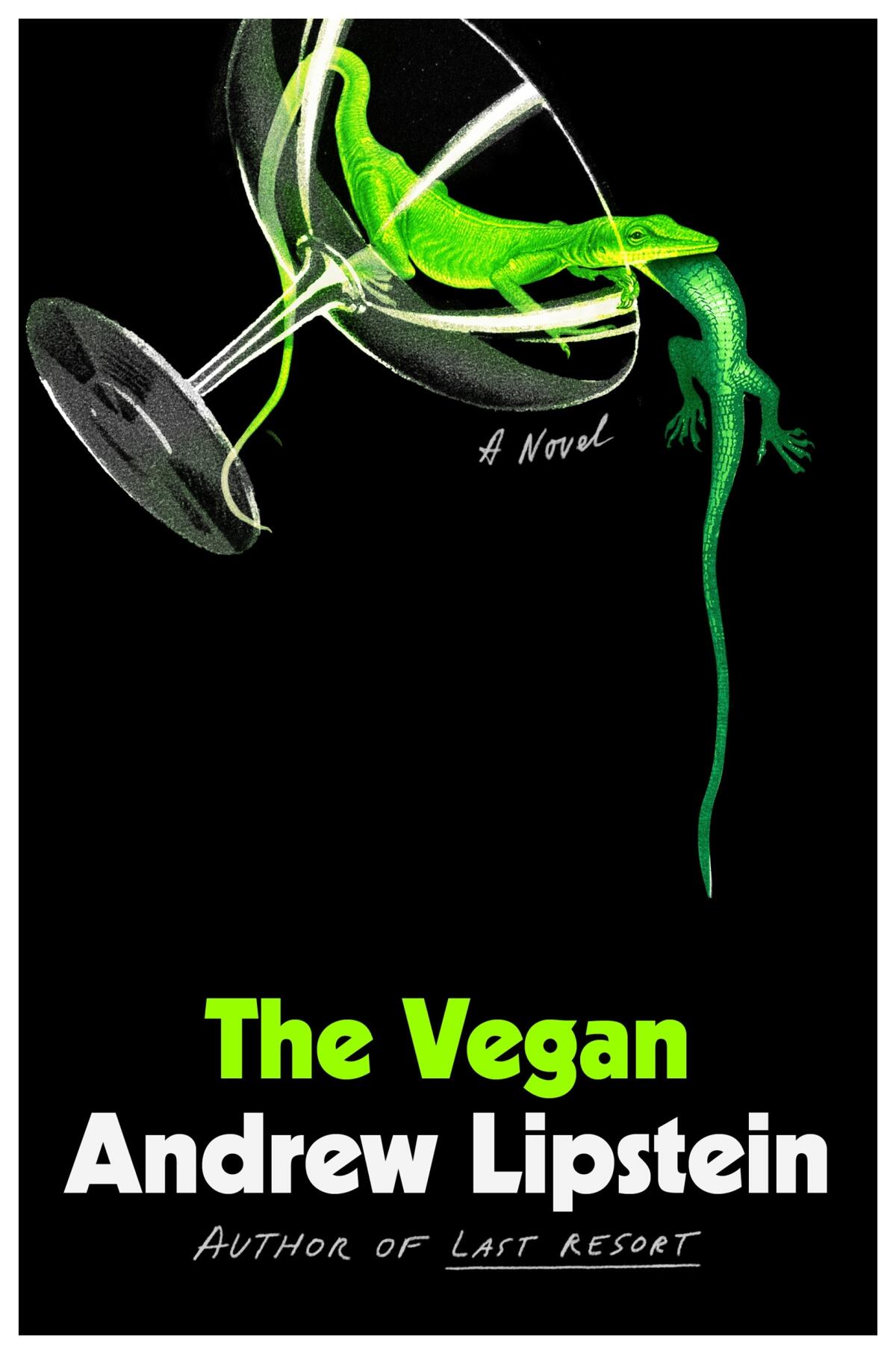

The Vegan

By Andrew Lipstein

FSG: 240 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Herschel Caine is in a hurry. He’s racing toward untold wealth thanks to his startup’s plan to revolutionize stock market investing; he’s grappling for social status, eager to impress his upscale but artsy Brooklyn neighbors; and he’s hurtling toward parenthood — in part, no surprise, to keep up with the folks next door.

In Andrew Lipstein’s “The Vegan,” Caine is white male privilege personified, and his poor judgment and impulsive behavior are both highly damaging and self-destructive.

Caine’s hedge fund is using proprietary technology developed by his partner that purportedly can more accurately predict stock prices … provided that Caine, as the front man, can raise hundreds of millions from some elusive, even shady characters — and quick.

Things start going sideways on the business front, but the real disaster occurs at home in Brooklyn when Birdie, an old friend of his wife Franny, joins them and the neighbors for dinner. Those neighbors: Clara, an interior designer, and Philip, a Guggenheim descendant who directs intellectual and agenda-driven films. (Franny is a furniture designer.)

The seven deadly sins of bad art friendship, fleetingly explored in a debut novel

Birdie is a successful British playwright, so Herschel and Franny are counting on her adding cultural cachet to their gathering. Instead, she drinks flamboyantly and dominates the conversation so unpleasantly that Herschel, desperate to be rid of her, dumps some ZzzQuil into her drink. This move works too well: Thinking she has drunk too much, Birdie finally excuses herself; while waiting for her Uber on the street, she slips and cracks her skull on the curb.

When Herschel learns Birdie is unlikely to emerge from the coma he inadvertently caused, he is suddenly and thoroughly put off by the idea of any animal sacrificing its life for his pleasure. Instantly, be becomes the vegan of the title. This change does little to assuage his guilt, nor does it help him cope with the secrets he has been keeping at work. He certainly doesn’t reconsider his master-of-the-universe aspirations or his status-seeking lifestyle.

Instead, Herschel just spirals: He accosts another neighbor because he thinks that with one glance, he has emotionally bonded with that man’s dog; he sneaks into the local zoo at night to try and commune with animals including a red panda that, unsurprisingly, wants nothing to do with him.

The bits we learn of Herschel’s backstory, including a childhood trauma he has only barely begun dealing with, make him more empathetic — until he commits his next unthinking act. He tries to get more in touch with nature without ever understanding it, a lesson he finally learns from the anoles he buys on yet another impulse. While Herschel isn’t really learning from each new mistake for much of the book, his interior searching gives Lipstein a chance to offer up thought-provoking commentary, even when it feels like self-justification.

In Caitlin Shetterly’s novel ‘Pete and Alice in Maine’ a financier and his family flee New York City’s 2020 COVID emergency and struggle to stay together.

At one point, Herschel notes that the couples he once saw as the most judgmental are now the most unhappy. “It was no small irony that their problem appeared to be, at its core, a crisis of morality,” Lipstein writes. “Sometimes it seemed as they treated virtue the way previous generations treated wealth: not just as a precondition for social acceptance but as something with only one number attached to it. They fetishized morality, practically, they forgot the very thing it was, that it was not about scale but priorities, that its power came from compromise, that two people might both strive to be good while having irreconcilable definitions of the term.”

Later, in a rant about our attachment to cellphones, he looks at how all technology has diminished us: “With every upgrade the human race wrought we saw more and more of ourselves and less and less of the world we’d opted out of, we grew only in confidence, we became bold in our ignorance, we became deranged, obsessed not with who we were but who we weren’t.”

For all the eloquent monologues, it sometimes feels as though Lipstein shoves Herschel into scenes that don’t feel natural. For instance, he attempts to briefly steal the neighbor’s dog — left alone on the leash outside — to feed it the meat he had thrown out. The ensuing argument between Herschel, the dog’s owner and Philip — who conveniently wanders over — is interesting in the abstract but feels manipulative in narrative terms.

Hudson Yards provides the ideal backdrop for “Succession’s” callow self-interest. Plus, bidding Sondheim adieu and “The Band’s Visit” lands in L.A.

On the other hand, when Herschel finally loses control of his own narrative, Lipstein cleverly shows this dissociation by switching from first to third person, with the reader understanding that it is Herschel narrating his own bad behavior (not just Lipstein writing it).

The bigger issue is Lipstein’s choice of targets. (The satirical butt of his debut novel, “Last Resort,” is a caddish failed novelist who steals another person’s story.) It’s easy to skewer empty strivers, and it definitely brings satisfaction to readers to see them get their comeuppance. But that’s different than writing a fully successful novel; creating a compelling story around such a ruthless capitalist and unpleasant mess of a man is a tricky business. “Succession” did this better than most, but it had the advantage of multiple monsters, brilliantly profane banter and mesmerizing actors.

Lipstein pushes his story at a propulsive clip and gives us plenty to think about, like the idea of whether an accident can also be somebody’s fault. But Herschel is the book’s only fully fleshed out character, and since he’s not only tough to stomach but an empty soul, “The Vegan,” for all its flavorful scenes, ultimately leaves you wishing for a little more red meat.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.