John McPhee calls his new book an “old-people project.” Consider the alternative

- Share via

On the Shelf

Tabula Rasa: Volume 1

By John McPhee

FSG: 192 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

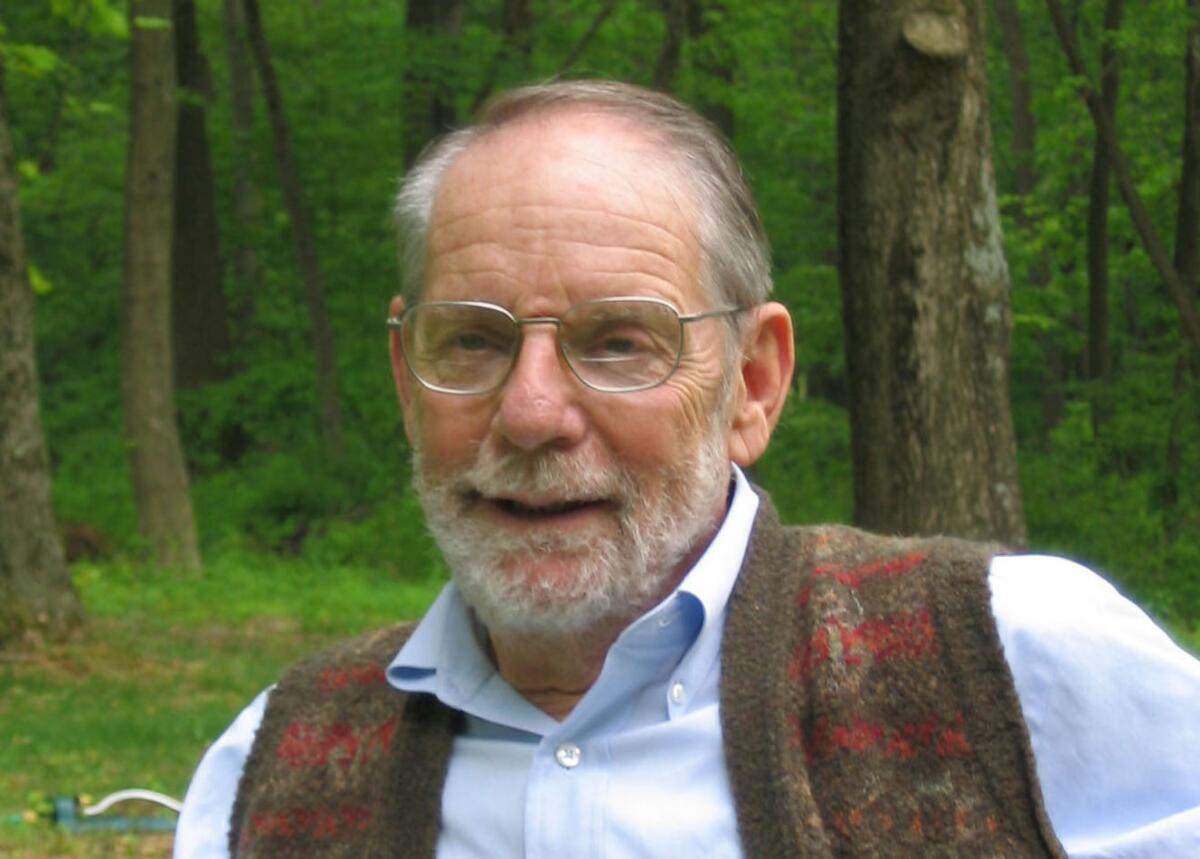

John McPhee, who turned 92 in March, would like to keep at it for a while — the writing, and the breathing. In his lively new collection, “Tabula Rasa,” the very longtime, very long-form journalist writes of “old-people projects,” the kinds of things we feel compelled to do when the end is a lot closer than the beginning. His favorite example is Mark Twain’s autobiography, which the “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” author dictated when he was in his 70s. Such projects, McPhee writes, give us purpose. “Old-people projects keep old people old,” he writes. “You’re no longer old when you’re dead. If Mark Twain had stayed with it, he would be alive today.”

“Tabula Rasa” is a delightful old-people project. These are sketches, anecdotes and ideas for stories and books that McPhee, a staff writer at the New Yorker since 1965, never got around to writing. You won’t find the raw materials for his magisterial 1999 Pulitzer-winning geology deep-dive “Annals of the Former World,” or “The Pine Barrens,” his 1968 jaunt through the famous New Jersey ecoregion. Working largely under storied New Yorker editor William Shawn, McPhee took full advantage of the magazine’s epic story parameters, writing at great length but with literary precision about his passions and obsessions.

“Tabula Rasa” offers more modest treats. Like memories of the time McPhee could have sworn he sat across a table from Hemingway in a bar in Spain, and his friendship with the novelist Peter Benchley (“Jaws”), who grew rich enough to retire but didn’t, because writers write. McPhee describes the joys of beelining — essentially road-tripping the shortest possible distance from one point to another. He writes about the maddening, sponsor-driven uptick in TV timeouts that disrupt sporting events at every opportunity.

In ‘Turn Every Page: The Adventures of Robert Caro and Robert Gottlieb,’ filmmaker Lizzie Gottlieb illuminates the decades-long collaboration between the LBJ biographer and his editor, her father.

McPhee remains a passionate fan of basketball and lacrosse, though his severe glaucoma keeps him from watching as he once did, and from teaching his hugely influential journalism courses at Princeton University (though he has not retired from the faculty, remaining active in the administration).

It is telling that McPhee’s random exercise in notebook-emptying proves a more pleasant read than most writers’ fully formed projects. That pleasure, as it turns out, isn’t all ours. In writing “Tabula Rasa,” McPhee, a legend of what is now often called creative nonfiction, found a replenishment of another quality that can lead to a long life: fun.

“Doing these pieces is fun, and writing isn’t fun, or it didn’t used to be,” he says by phone from his lifelong hometown of Princeton, N.J. “For 50 years, it wasn’t fun. You’re usually on edge about it, and you doubt yourself. If you didn’t, you wouldn’t be able to edit your own pieces, you wouldn’t be able to evaluate what you’re doing.

“The nervous anxiety over how something’s going every day, it goes with the territory and I think it’s important,” he continues. “But it isn’t true with these pieces. They’re very short. You get into one and out the other side before you know what happened. It’s just been a very pleasant and utter contrast to the grousy curmudgeon who was there before.”

Before the theory of plate tectonics--that is to say, before about 1968--those of us who went to college with underdeveloped right brains frequently fulfilled the university science requirement by suffering through two semesters of geology, a subject we incorrectly imagined might prove more comprehensible than physics or chemistry or statistics.

McPhee’s sentiment brings to mind an old quip attributed to Dorothy Parker: “I hate writing, I love having written.” By contrast, it has always been a gleeful experience to read McPhee, whether the topic is geology, which he makes exciting even to the science-averse layman, or Bill Bradley, the former Princeton basketball star and U.S. senator whom McPhee profiled for the New Yorker in 1965 — and who remains a dear friend.

McPhee is one of the all-time great generalists, a writer who can go to town on just about any subject, so long as the passion and interest move him. “You say to yourself, ‘That’s really interesting,’” he explains. “Well, then I want to turn around and tell you about it. And that was true of me when I was a little kid. I would go home and report things to my older brother and sister, and I wanted them to be interested in what the hell I had to say.”

But he never had much use for make-believe. When it comes to storytelling, he has always been like Joe Friday on “Dragnet.” Just the facts, though rendered in minute, poetic detail. “I’m interested in passing along what I find fascinating.”

McPhee is already hard at work on a second volume of “Tabula Rasa” (Latin for “clean slate”). “I now have about 25,000 words of stuff that nobody’s seen yet,” he says. “In other words, I’m still at it. And I have a contract that calls for Volume 2, Volume 3, and Volume 4. The idea is I never die, see.”

In recent years, the writer John McPhee has stepped away from lucidly detailing complex structures like rocks and lacrosse plays, and has instead taken himself — and his 55 years working for the New Yorker — as his subject.

McPhee’s approach is a moving twist on the idea of writerly immortality. We tend to think it’s the endurance of the work that allows the greats — Shakespeare, Toni Morrison, Cormac McCarthy — to live forever. For McPhee, it’s the creation of the work that keeps him pushing through another year, another book (32 and counting), another sentence.

The idea is he never dies, see. So far, it’s worked out for him — and for us.

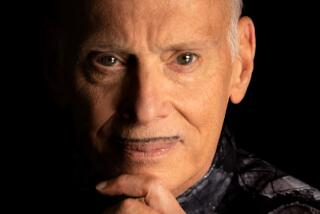

Vognar is a freelance writer based in Houston.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.